|

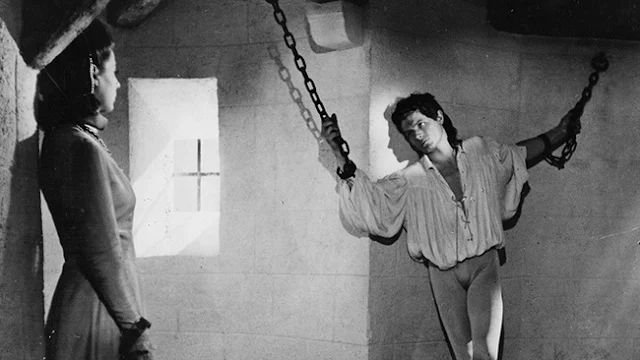

| Joan Collins in Land of the Pharaohs |

Cast: Jack Hawkins, Joan Collins, Dewey Martin, Alexis Minotis, James Robertson Justice, Luisella Boni, Sydney Chaplin, James Hayter, Kerima, Piero Giagnoni. Screenplay: William Faulkner, Harry Kurnitz, Harold Jack Bloom. Cinematography: Lee Garmes, Russell Harlan. Art direction: Alexandre Trauner. Film editing: Vladimir Sagovsky. Music: Dimitri Tiomkin.

Why has there never been a really good movie about ancient Egypt? Is it that we can't imagine those ancient peoples in any other terms than the sideways-walking figures on old walls? Archaeologists have uncovered enough about their daily lives, their customs and their religion, that it might be possible to put together a plausible story set in those times, but eventually filmmakers turn to spectacle, with lots of crowds and opulently fitted palaces inhabited by kings and courtiers wearing lots of gold and jewels. Land of the Pharaohs was an attempt by one of the great producer-directors of his day, Howard Hawks, enlisting none other than William Faulkner as a screenwriter. It, too, laid on the usual ancient frippery and a cast of thousands, and it was a box-office bomb, eliciting some critical sneers. More recently, it has attracted some admirers, including Martin Scorsese, though only as a "guilty pleasure." Hawks himself admitted that one of the problems he and the writers faced was that they "didn't know how a pharaoh talked," and Hawks was always a master of movies with good talk. So while it's impossible to take seriously, Land of the Pharaohs provides a good deal of entertainment, even if only of the sort derived from making fun of the movie. Though it's not ineptly made, it's also impossible to take seriously, especially when Joan Collins is vamping around.