|

| Jeanne Moreau and Marcello Mastroianni in La Notte |

Giovanni Pontano: Marcello Mastroianni

Valentina Gherardini: Monica Vitti

Tommaso Garani: Bernhard Wicki

Gherardini: Vincenzo Corbella

Signora Gherardini: Gritt Magrini

Roberto: Giorgio Negro

Director: Michelangelo Antonioni

Screenplay: Michelangelo Antonioni, Ennio Flaiano, Tonino Guerra

Cinematography: Gianni Di Venanzo

Production design: Piero Zuffi

Film editing: Eraldo Da Roma

Music: Giorgio Gaslini

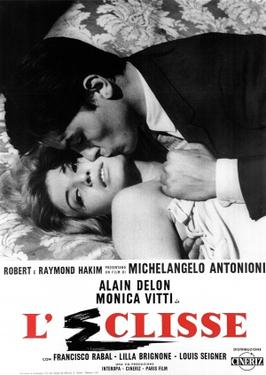

Movie stars often provide a shortcut to establishing the backstories of the characters they play. Once we see the bruised intelligence of Jeanne Moreau and the weary elegance of Marcello Mastroianni, familiar to us from their previous films, we know something about their characters, Lidia and Giovanni Pontano, that the screenplay for Michelangelo Antonioni's La Notte doesn't need to tell us. We know there will be tension in their marriage, that Lidia will go for long solitary walks and that Giovanni will yield to almost any temptation that crosses his path. Giovanni is a successful writer, but the money that affords them a handsome apartment in Milan mostly comes from her, which gives her one reason to feel resentful when she's shunted aside by his celebrity. So La Notte is mostly about her lonely search for a raison d'etre while he indulges himself with the pleasures of the moment: the come-on of a sex-crazed woman in a hospital, a celebratory book-signing, a night club floor show, a flirtation with the beautiful daughter of an industrialist, a lucrative job offer from that industrialist. Lidia even seems to be trying to find ways of indulging herself the way her husband does: On her long walk through Milan, she plays at being a prostitute, throwing backward glances at men she passes on the street, though never making the essential connection. She tries to break up a fight between two young men from what seem to be rival street gangs, but when the shirtless victor of the fight pursues her, she flees. She gets a kind of erotic charge from watching a group set off skyrockets. And she escapes from the industrialist's elaborate all-night party, a kind of tepid orgy manqué, with a handsome young man, only to stop in mid-dalliance and ask him to return her to the party. And so at the end of the film we leave the Pontanos grappling in the dirt as the dawn appears, somehow destined to continue their perverse games. La Notte has more narrative coherence than the other two Antonioni films usually thought of as a trilogy, L'Avventura (1960) and L'Eclisse (1962), which makes it essential in understanding what the director is up to. I take the currently prevailing view that Antonioni is less interested in existential alienation than in the lives of women in a society that valorizes male aggression. Hence the pivotal scene in which Lidia meets Valentina, the industrialist's daughter who has been toying with her husband, and instead of fighting they reach a kind of understanding, an assertion of female moral superiority.