|

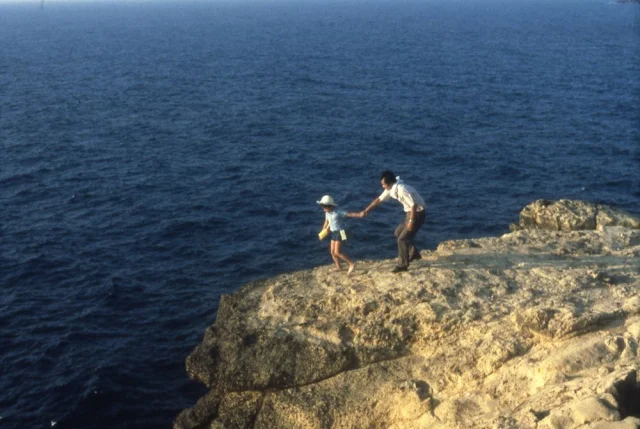

| Yusuke Kawazu and Miyuki Kuwano in Cruel Story of Youth |

Makoto: Miyuki Kuwano

Kiyoshi: Yusuke Kawazu

Yuki: Yoshiko Kuga

Dr. Akimoto: Fumio Watanabe

Horio: Hiroshi Nihon'yanagi

Director: Nagisa Oshima

Screenplay: Nagisa Oshima

Cinematography: Takashi Kawamata

Music: Riichiro Manabe

In addition to the shamelessly exploitative title

Naked Youth,

Cruel Story of Youth has also been released as

A Story of the Cruelties of Youth. So is it the story that's cruel or the youth in it? Those who know Japanese can probably tell me which is closer to the original title,

Seishun Zankoku Monogotari, but I suspect the ambiguity is intentional. It's a cruel story about cruel young people, with the usual implication that society -- postwar, consumerist, America-influenced Japan -- is to blame for the cruelties inflicted upon and by them. With its hot pops of color and unsparing widescreen closeups, the film puts us uncomfortably close to its young protagonists, Makoto and Kiyoshi. Makoto is just barely out of adolescence -- Miyuki Kuwano was 18 when the film was made -- but carelessly determined to grow up fast. She hangs out in bars and cadges rides with middle-aged salarymen until the night when one of them decides to take her to a hotel instead of her home. When she refuses, he tries to rape her. But a young passerby intervenes and beats the man, threatening to take him to the police until the man hands over a walletful of money. The next day, Makoto and her rescuer, Kiyoshi, meet up to spend the money together. He's just a bit older -- Yusuke Kawazu was 25, three years younger than the film's director, Nagisa Oshima -- and over the course of their day together on a river he slaps her around, pushes her into the water and taunts her when she can't swim, and seduces her with his mockery of her inquisitiveness about sex. When he doesn't call her again, she seeks him out and they become lovers. They also become criminals: She goes back to her game of hooking rides with salarymen and he follows them, choosing a moment when the men start to get handsy with Makoto -- sometimes she provokes them to do so -- to beat and rob them. Naturally, things don't get better from here on out, especially after Makoto gets pregnant. We can object to the film's sentimental attempt to redeem Kiyoshi, who starts out as an abusive young thug but is transformed by love, and there's some awkward coincidence plotting, like an abortionist who turns out to be Makoto's sister's old boyfriend. But Oshima's portrait of a lost generation has some of the power of the American films that inspired it,

Rebel Without a Cause (Nicholas Ray, 1955) and

Gun Crazy (Joseph H. Lewis, 1950), as well as the French New Wave films about the anomie of the young by Claude Chabrol and Jean-Luc Godard. It was only Oshima's second feature, but it signaled the start of a major career.

Turner Classic Movies