A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Tatsuya Nakadai. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Tatsuya Nakadai. Show all posts

Monday, November 18, 2019

Belladonna of Sadness (Eiichi Yamamoto, 1973)

Belladonna of Sadness (Eiichi Yamamoto, 1973)

Cast: voices of Tatsuya Nakadai, Aiko Nagayama, Katsuyuki Ito, Shigako Shimegi, Masaya Takahashi, Natsuka Yashiro, Masakane Yonekura. Screenplay: Yoshiyuki Fukuda, Eiichi Yamamoto. Cinematography: Shigeru Yamazaki. Production design: Kuni Fukai. Animation: Gisburo Sugii. Music: Masahiko Sato.

There are images of extraordinary beauty and sinister power in Belladonna of Sadness, but they are also mixed with Pop Art clichés; psychedelia borrowed from Peter Max and his acolytes, album covers, and the Beatles' film Yellow Submarine (George Dunning, 1968); and kitsch reminiscent of greeting cards and nudie illustrations from back issues of Playboy. That is to say, it's a mixed bag. There seems to have been at some point an attempt to turn the film's fable into a feminist statement, but the link of the story of a violated woman who turns into a witch with the role of women in the French Revolution is tacked on unconvincingly at the film's end. Nevertheless, it's like no other animated film I've seen, and not just because its images have a striking, violent erotic content. The story is about Jeanne, who on the night of her wedding to Jean is subjected to the ruler's droit de seigneur, but not just to him: She is raped by his courtiers as well. Trigger warnings are appropriate at this moment, because the rape is signified by images of Jeanne being torn apart with a torrent of blood that fills the screen. Eventually, Jeanne is tempted by the devil (a terrific voice performance by Tatsuya Nakadai), who appears to her in the form of a penis (no kidding). She allows him to possess her body but not her soul, and through various episodes, including a harrowing treatment of the Black Death, she prevails, striking out against nobility and the church. At one point she "liberates" the peasantry by means of an orgy, a sexual fantasy that is both astonishing and sometimes hilarious. Eventually, she is caught and burned at the stake, but the implication is that, like her namesake Jeanne D'Arc's, her cause will prevail. The film's vision is ultimately incoherent, but its audacity is worth experiencing.

Friday, August 30, 2019

Hunter in the Dark (Hideo Gosha, 1979)

Cast: Tatsuya Nakadai, Yoshio Harada, Shin'ichi Chiba, Ayumi Ishida, Keiko Kishi, Ai Kanzaki, Kayo Matsuo, Tetsuro Tanba. Screenplay: Hideo Gosha, based on a novel by Shotaro Ikenami. Cinematography: Tadashi Sakai. Film editing: Michio Suwa. Music: Masaru Sato.

Colorful but rather confusing film about an 18th-century Japanese crime lord, played by Tatsuya Nakadai, who hires a one-eyed bodyguard with amnesia, played by Yoshio Harada. Violent confrontations ensue.

Tuesday, July 24, 2018

Black River (Masaki Kobayashi, 1957)

|

| Tatsuya Nakadai and Ineko Arima in Black River |

Nishida: Fumio Watanabe

Killer Joe: Tatsuya Nakadai

Landlady: Isuzu Yamada

Okada: Tomo'o Nagai

Okada's Wife: Keiko Awaji

Kurihara: Eijiro Tono

Kin: Seiji Miyaguchi

Sakazaki: Asao Sano

Director: Masaki Kobayashi

Screenplay: Zenzo Matsuyama

Based on a story by Takeo Tomishima

Cinematography: Yuharu Atsuta

Production design: Ninjin Kurabu

Film editing: Yoshiyasu Hamamura

Music: Chuji Kinoshita

Masaki Kobayashi's remarkable slice-of-life drama Black River takes place in a slum near an American army base. It's a festering dump, inhabited by a variety of people, from lowlifes attempting to make a living by exploiting the soldiers to dead-enders with no place else to go. Into this morass wanders a naïve university student, Nishida, in search of cheap lodgings, who tries to make a little money as a used-book seller. He falls for a pretty waitress, Shizuko, who longs to escape from the slum, but their attachment puts him in the line of fire of a swaggering young gangster called Killer Joe, who has his own designs on Shizuko. Presiding over everything is the landlady, who has plans for the property that don't include its tenants. She's played to a fare-thee-well by the great Isuzu Yamada, perhaps best known as the Lady Macbeth equivalent in Akira Kurosawa's Throne of Blood (1957). Here she's outfitted with a snaggly golden-toothed grill, a fitting correlative for the concealment of the moral rot within. But the real scene-stealer of the film is Tatsuya Nakadai as Killer Joe, in one of his first major film appearances, perfectly blending the charisma that would make him a star with the menace that would allow him to play memorable villains as well as heroes.

Sunday, June 10, 2018

Ran (Akira Kurosawa, 1985)

|

| Jinpachi Nezu and Mieko Harada in Ran |

Taro Takatora Ichimonji: Akira Terao

Jiro Masatora Ichimonji: Jinpachi Nezu

Saburo Naotora Ichimonji: Daisuke Ryo

Lady Kaede: Mieko Harada

Lady Sué: Yoshiko Miyazaki

Shuri Kurogane: Hisashi Igawa

Kyoami: Pîtâ

Tango Hirayama: Masayuki Yui

Director: Akira Kurosawa

Screenplay: Akira Kurosawa, Hideo Oguni, Masato Ide

Based on a play by William Shakespeare

Cinematography: Asakazu Nakai, Takao Saito, Shoji Ueda

Production design: Shinobu Muraki, Yoshiro Muraki

Film editing: Akira Kurosawa

Music: Toru Takemitsu

Costume design: Emi Wada

Lavish in color and pattern, Ran may be Akira Kurosawa's most pictorial film, to the point that the images and costumes and sets sometimes threaten to overwhelm the human drama at its core. To the extent that this is Kurosawa's second effort at translating a Shakespeare play into medieval Japanese terms, I have to say that I prefer his adaptation of Macbeth, the 1957 Throne of Blood, to this reworking of King Lear. It seems to me that in Ran, Kurosawa stumbles over the analogous figures from Shakespeare in ways that he doesn't in his earlier film. Turning Lear's daughters into Hidetora's sons robs much of the delicacy and painful sadness of the Shakespeare play, especially in the final reunion of Lear and Cordelia. And King Lear is a more complex play than Macbeth, with its intricate subplot involving Gloucester and his sons, and the multiple intrigues of the households of Goneril and Regan. Kurosawa has pared down and fused some of these secondary stories, but he still loses sight at times of his central figure, the Lear analog, Lord Hidetora. Tatsuya Nakadai is unquestionably one of the world's great film actors, but he's too sturdy a figure for the enfeebled Hidetora, and the stylized old-age makeup often hides his features -- except for the great, glaring eyes. There are grand things, however, in the film, including a wonderfully villainous performance by Mieko Harada as the Lady Kaede, and a curiously effective Fool, performed by the androgynous actor-dancer known as Pîtâ.

Sunday, May 6, 2018

The Scandalous Adventures of Buraikan (Masahiro Shinoda, 1970)

|

| Tatsuya Nakadai in The Scandalous Adventures of Buraikan |

Michitose: Shima Iwashita

Soshun Kochiyama: Tetsuro Tanba

Ushimatsu: Shoichi Ozawa

Moritaya Seizo: Fumio Watanabe

Okuna, Naojiro's Mother: Suisen Ichikawa

Kaneko Ichinojo: Masakane Yonekura

Kanoke-boshi: Jun Hamamura

Director: Masahiro Shinoda

Screenplay: Shuji Terayama

Based on a play by Mokuami Kawatake

Cinematography: Kozo Okazaki

Art direction: Shigemasa Toda

Film editing: Yoshi Sugihara

Music: Masaru Sato

I think I was culturally ill-equipped for The Scandalous Adventures of Buraikan, a wittily stylized film that presupposes an acquaintance with Japanese history and culture that I don't possess. From my own culture, I bring a knowledge of 18th-century portrayals of London lowlife, such as the pictures of Hogarth and the satire in John Gay's The Beggar's Opera. Buraikan has echoes for me of those, as well as, in its portrayal of the puritanical reformer's zeal, Shakespeare's Measure for Measure. But for much of the film I felt at sea.

Monday, March 19, 2018

Immortal Love (Keisuke Kinoshita, 1961)

|

| Hideko Takamine, Tatsuya Nakadai, and Yoshi Kato in Immortal Love |

Heibei: Tatsuya Nakadai

Takashi: Keiji Sada

Tomoko: Nobuko Otowa

Yutaka: Akira Ishihama

Naoko: Yukiko Fuji

Sojiro: Yoshi Kato

Rikizo: Kiyoshi Nonomura

Eiichi: Masakazu Tamura

Morito: Masaya Totsuka

Heizaemon: Yasushi Nagata

Director: Keisuke Kinoshita

Screenplay: Keisuke Kinoshita

Cinematography: Hiroshi Kusuda

Art direction: Chiyoo Umeda

Film editing: Yoshi Sugihara

Music: Chuji Kinoshita

I'm a little surprised to find that Keisuke Kinoshita's screenplay for Immortal Love is "original." The film has the feeling of an adaptation from one of those doorstop "sins of the father" family sagas like East of Eden. It's full of melodramatic moments, including at least one rape and several suicide attempts, including a successful one in which the character jumps into a volcano. It spans three decades and is loaded with enough plot and characters to fill a much longer film, which is why it sometimes seems a little skimpy. The plot is set in motion when Heibei, the son of a wealthy landowner, returns from the invasion of Manchuria in 1932 with a crippling war injury. He spies the pretty Sadako, the daughter of one of his father's tenants, but she loves Takashi, another tenant farmer's son who has also served in China. When Takashi returns he finds that Sadako has been raped by Heibei and is set to marry him. As the years pass, Sadako stays with Heibei, tending to him and his aging father, and bearing three children -- one of whom was conceived during the rape, a fact that will develop into a plot point. Takashi marries and moves away, but his wife, Tomoko, bears a kind of grudge against Sadako, her husband's first love. And things get complicated as the children grow up. The film works largely because of the actors, even though both Hideko Takamine and Tatsuya Nakadai, considerable performers, seem a little stretched to put across their characters. Heibei, for example, comes across as a deep-dyed villain until the very end, despite some closeups in which Nakadai seems to be trying to suggest the character's remorse for his villainy. And Takamine is faced with playing the dutiful wife to a man she despises, undermining him secretly and passive-aggressively. It's a tribute to both actors that they make the film as watchable as it is. Kinoshita tries some things that don't really work, like a ballad that bridges the time gaps between "chapters" (of which there are five), and the guitar-based score by his brother, Chuji Kinoshita, sounds like flamenco -- an odd choice for the very Japanese story and setting. Even the title given it for American distribution is askew -- none of the loves depicted in it seem particularly deathless. It was released in the United Kingdom as Bitter Spirit, which seems more appropriate. The film was Japan's entry for the foreign language film Oscar; it made the shortlist but lost to Ingmar Bergman's Through a Glass Darkly.

Sunday, March 11, 2018

The Human Condition III: A Soldier's Prayer (Masaki Kobayashi, 1961)

|

| Tatsuya Nakadai in The Human Condition III: A Soldier's Prayer |

Michiko: Michiyo Aratama

Shojo: Tamao Nakamura

Terada: Yusuke Kawazu

Choro: Chishu Ryu

Tange: Taketoshi Naito

Refugee Woman: Hideko Takamine

Ryuko: Kyoko Kishida

Russian Officer: Ed Keene

Chapayev: Ronald Self

Director: Masaki Kobayashi

Screenplay: Zenzo Matsuyama, Koichi Inagaki, Masaki Kobayashi

Based on a novel by Junpei Gomikawa

Cinematography: Yoshio Miyajima

Art direction: Kazue Hirataka

Film editing: Keiichi Uraoka

Music: Chuji Kinoshita

Homer's Odysseus made it home to Ithaka and Penelope, but Masaki Kobayashi's Odysseus, Kaji, doesn't make it home to his Penelope, Michiko, and he's not certain that his Ithaka in southern Manchuria still exists. Kaji struggles toward her against all odds, but dies in a snowstorm, without even a moment of transcendence or a heavenly choir on the soundtrack to ennoble his death. It's a downer ending to a nine-hour epic, but if it feels right it's thanks to the enormous conviction of Tatsuya Nakadai as the stubborn idealist Kaji. The Human Condition is an immersive experience rather than a dramatic one: Drama would demand catharsis, and there is really none to be had from the film. The human condition depicted in the film is Hobbesian: solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short -- though the length of the film works against the last adjective. It is a statement film: War is a stupid way for people to behave to one another. And as such it never quite transcends its message-making, leaving the film somewhere short of greatness. Still, it has to be seen by anyone who seeks to understand Japan in the twentieth century and after, and by anyone who wants to know the limits of film as an art form.

Friday, March 9, 2018

The Human Condition II: Road to Eternity (Masaki Kobayashi, 1959)

|

| Tatsuya Nakadai in The Human Condition II: Road to Eternity |

Michiko: Michiyo Aratama

Shinjo: Kei Sato

Obara: Kunie Tanaka

Yoshida: Michiro Minami

Kageyama: Keiji Sada

Sasa Nitohei: Kokinji Katsura

Hino Jun'i: Jun Tatara

Director: Masaki Kobayashi

Screenplay: Zenzo Matsuyama, Masaki Kobayashi

Based on a novel by Junpei Gomikawa

Cinematography: Yoshio Miyajima

Art direction: Kazue Hirataka

Film editing: Keiichi Uraoka

Music: Chuji Kinoshita

If, as I said yesterday, the first part of Masaki Kobayashi's The Human Condition makes me think of the earnest "serious pictures" that came out of Hollywood in the 1940s -- I have in mind such movies as The Razor's Edge (Edmund Goulding, 1946), in which Tyrone Power searches for the meaning of life, or Gentleman's Agreement (Elia Kazan, 1947), in which Gregory Peck crusades against antisemitism -- then the second part, Road to Eternity, suggests, even in its subtitle, the influence of From Here to Eternity (Fred Zinnemann, 1953), that near-scathing* look at brutality in Army basic training. Kaji, our idealistic protagonist, has been sent to war, and has to endure all manner of abuse even though he's an excellent marksman and a sturdy trooper. His objections to Japanese militarism and his belief that the war is wrong mark him out as a "Red," and for a time he contemplates escaping into his idealized version of the Soviet Union. But his sympathy for his fellow recruits keeps him plugging away, occasionally taking heat for his defense of them, especially from the military veterans who have been called up to serve. They object to his treating the recruits he is put in charge of training with respect and human decency -- they went through hell in basic training, so why shouldn't everyone? The film ends with a cataclysmic battle sequence, during which Kaji has to kill one of his fellow soldiers, who has gone stark raving mad and with his antics threatens the lives of other soldiers. It's not the first time Kaji has resorted to killing a fellow soldier: Earlier, he has been mired in quicksand with a brutal man who has caused the suicide of a recruit, and Kaji lets him drown. The intensity of the battle scenes takes some of the focus away from Kaji's intellectualizing, which is all to the good.

*I have to quality: From Here to Eternity is not as scathing as the James Jones novel on which it's based, thanks to the Production Code and the residual good feeling of having won the war. In some ways, The Human Condition II is more properly an anticipation of Stanley Kubrick's no-holds-barred

Full Metal Jacket (1987).

Thursday, March 8, 2018

The Human Condition I: No Greater Love (Masaki Kobayashi. 1959)

|

| Tatsuya Nakadai and So Yamamura in The Human Condition I: No Greater Love |

Michiko: Michiyo Aratama

Tofuko Kin: Chikage Awashima

Shunran Yo: Ineko Arima

Kageyama: Keiji Sada

Okishima: So Yamamura

Chin: Akira Ishihama

Director: Masaki Kobayashi

Screenplay: Zenzo Matsuyama, Masaki Kobayashi

Based on a novel by Junpei Gomikawa

Cinematography: Yoshio Miyajima

Art direction: Kazue Hirataka

Film editing: Keiichi Uraoka

Music: Chuji Kinoshita

The first three and a half hours of Masaki Kobayashi's nine-hour, 47-minute epic The Human Condition are themselves divided into two parts, though the break seems more a courtesy to the Sitzfleisch of the viewer than to any inherent division in the story. I have a friend who says he's never read a bad novel over 600 pages long, because once he's done with it he has to justify the time spent reading. I think something like that may apply to The Human Condition once I've finished it. Which is not to say that there isn't a greatness that adheres to Kobayashi's unsparing, audacious film, even though at times I found myself feeling that The Human Condition I: No Greater Love derived as much from the more earnest black-and-white Hollywood films of the 1940s, the ones that starred Tyrone Power or Gregory Peck, than from the high artistry of Ozu or Mizoguchi. It is often unabashed melodrama: We worry that Kobayashi hasn't burdened his protagonist, Kaji, with more than is really credible. An idealist, he not only finds himself supervising slave Chinese labor in Manchuria during World War II, he also has to manage a brothel staffed with Chinese "comfort women." And the more he does to better the lot of the workers, the more he elicits the ire of the kenpeitai, the Japanese military police. On the other hand, if he compromises with the authorities, the Chinese prisoners and prostitutes make his life miserable. And not to mention that, his wife is incapable of comprehending the stresses that make him so distant at home. But Tatsuya Nakadai is such an accomplished actor that he gives Kaji credibility, even when we're beginning to think he's too virtuous, too idealistic, for his own good.

Monday, February 26, 2018

The Inheritance (Masaki Kobayashi, 1962)

|

| Keiko Kishi in The Inheritance |

Senzo Kawahara: So Yamamura

Kikuo Furukawa: Tatsuya Nakadai

Satoe Kawahara: Misako Watanabe

Naruto Yoshida: Seiji Miyaguchi

Junichi Fujii: Minoru Chiaki

Mariko: Mari Yoshimura

Sadao: Yusuke Kawazu

Director: Masaki Kobayashi

Screenplay: Koichi Inagaki

Based on a novel by Norio Najo

Cinematography: Takashi Kawamata

Art direction: Shigemasa Toda

Film editing: Keiichi Uraoka

Music: Toru Takemitsu

Looking as chic and mysterious as Anouk Aimée, Delphine Seyrig, or Monica Vitti ever did in the French and Italian films of the era, Yasuko Miyagawa steps from her car, dons her sunglasses, and goes for a bit of window-shopping. But in front of a jewelry store window, she is stopped by a man she once knew. She agrees to join him in a cafe, where the flashback that constitutes most of Masaki Kobayashi's The Inheritance unfolds in her narrative. When they knew each other, she was a secretary and he was a lawyer for the wealthy businessman Senzo Kawahara, and both of them had key roles in determining who would benefit from Kawahara's will. The rest is a noir fable, based on the oldest of plot premises: Where there's a will, there are people scheming to benefit from it. Upon learning that he has cancer and only a short while to live, Kawahara set his managers the task of locating his illegitimate children: He and his wife, Satoe, have none from their marriage. And in the search for the heirs, even the searchers are prone to make deals with the potential legatees. By law, Satoe stands to inherit a third of her husband's 300 million yen estate, but she of course wants more, which means making sure that none of her husband's offspring earns his favor. And then there are the offspring, some of whom have adoptive families that would benefit from being included in the will, while others have come of age and want to curry favor with the father they've never met. No holds are barred: not only fraud but also murder and rape. But mainly the film is the story of Yasuko, beautifully played by Keiko Kishi, transforming from the self-effacing secretary into the consummate schemer, motivated at least as much by revenge as by greed. It's a nasty tale, but an involving one.

Thursday, February 8, 2018

When a Woman Ascends the Stairs (Mikio Naruse, 1960)

|

| Hideko Takamine and Daisuke Kato in When a Woman Ascends the Stairs |

Kenichi Komatsu: Tatsuya Nakadai

Junko Inchihashi: Reiko Dan

Nobuhiko Fujisaki: Masayuki Mori

Matsukichi Sekine: Daisuke Kato

Yuri: Keiko Awaji

Goda: Ganjiro Nakamura

Minobe: Eitaro Ozawa

Tomoko: Chieko Nakakita

Director: Mikio Naruse

Screenplay: Ryuzo Kikushima

Cinematography: Masao Tamai

Production design: Satoru Chuko

Film editing: Eiji Ooi

Music : Toshiro Mayuzumi

If I ran a revival house like the Stanford Theater in Palo Alto or the Castro in San Francisco, I'd like to program a series of double features of American and Japanese "women's pictures." It would give us a chance to compare not only directors like Douglas Sirk and Mikio Naruse but also the actresses most associated with the genre: Joan Crawford, Jane Wyman, and Lana Turner on the one hand; Kyoko Kagawa, Setsuko Hara, and Hideko Takamine on the other. Takamine is the woman who ascends the stairs in Naruse's film, only to hit something like a glass ceiling. She plays Keiko (at first a little confusingly, at least to Western audiences, called "Mama"), a Ginza bar hostess whose job it is to bring in paying customers, especially rich ones,who will while away their after-office hours flirting with her and the fleet of bar girls. She doesn't sleep with the customers -- even the younger women aren't expected to, but sometimes do -- and though she drinks with them, she doesn't particularly like alcohol. But Keiko is on the brink of turning 30, and when the bar starts losing customers to a younger hostess named Yuri, who has left Keiko's establishment to start her own, she begins to see what a dead-end she faces. She doesn't own the bar where she works, and the woman who does is beginning to blame her for losing customers and for not wearing flashier kimonos. She supports her mother and somewhat feckless brother, who has a son who needs an operation to correct a defect left by polio.She begins to hate climbing the stairs to the bar every night and the stress brings on a peptic ulcer, but she can see only three options for her life: Marry, become the mistress of a wealthy patron, or buy her own bar. Each of these opportunities presents itself during the course of the film, only to end in disappointment, and at the end she is climbing the stairs again. Takamine is marvelous, so expressive that we hardly need her voiceover narration to know what she's feeling and thinking, and she's well-supported by Reiko Dan as the younger, more carefree bar girl; Tatsuya Nakadai as the bar's handsome young business manager, who's in love with Keiko; Daisuke Kato as the chubby customer who proposes a marriage to Keiko that she accepts before learning that he's already married and a constant philanderer;and Masayuki Mori as the potential wealthy patron with whom, in a moment of drunken abandonment, she sleeps, only to learn the next morning that he's moving to Osaka.When a Woman Ascends the Stairs is a beautifully made account of problems specific to a time, a place, and a gender, yet universal in its depiction of the frustrations of the working life.

Wednesday, December 27, 2017

Sanjuro (Akira Kurosawa, 1962)

|

| Toshiro Mifune, Takako Irie, and Reiko Dan in Sanjuro |

Hanbei Muroto: Tatsuya Nakadai

The Spy: Keiju Kobayashi

Iori Izaka: Yuzo Kayama

Chidori: Reiko Dan

Kurofuji: Takashi Shimura

Takebayashi: Kamatari Fujiwara

Mutsuta's Wife: Takako Irie

Kikui: Masao Shimizu

Mutsuta: Yunosuke Ito

Director: Akira Kurosawa

Screenplay: Ryuzo Kikushima, Hideo Oguni, Akira Kurosawa

Based on a novel by Shugoro Yamamoto

Cinematography: Fukuzo Koizumi, Takao Saito

Production design: Yoshiro Muraki

Music: Masaru Soto

Akira Kurosawa's tongue-in-cheek Sanjuro is not so much a sendup of samurai films as it is an effort to carry a genre to its logical and sometimes absurd extremes, the way the James Bond movies took spy films to a point of exciting but improbable and often comic point of no return. It reaches its peak in the final combat between Sanjuro and Hanbei, with an explosion of gore (produced by a pressurized hose that nearly knocked actor Tatsuya Nakadai off his feet) that's surprising and shocking but also very funny once you put it in the context of the usual bloodless deaths of samurai films. But Kurosawa has made us aware of the just-a-movie unreality of Sanjuro's action throughout, with his careful arrangements of the nine samurai under the spell of the sloppy ronin who calls himself "Sanjuro Tsubaki," which means something like "30-year-old camellia," a name he makes up on the spot. The not-so-magnificent nine are always grouping themselves for the camera, either in little triple triads or in chains that fill the widescreen. Their arrangements come to annoy Sanjuro so much that once, when they're trying to sneak up on someone, he tells them not to move in single file behind him: "We look like a centipede!" In addition to Mifune's irresistible scene-stealing, there's a delightful comic performance by Takako Irie as Mutsuta's wife, dithery and concerned with propriety, but also with a fund of commonsense that Sanjuro wisely heeds. Tatsuya Nakadai is wasted as the villain who's the only plausible challenger to the hero -- a kind of Basil Rathbone to Mifune's Errol Flynn -- a role that otherwise doesn't give Nakadai much to do but glare at the fools he's allied with.

Saturday, November 4, 2017

The Sword of Doom (Kihachi Okamoto, 1966)

|

| Tatsuya Nakadai in The Sword of Doom |

Ohama: Michiyo Aratama

Hyoma Utsuki: Yuzo Kayama

Omatsu: Yoko Naito

Taranosuke Shimada: Toshiro Mifune

Shichibei: Ko Nishimura

Bunnojo Utsuki: Ichiro Nakaya

Kamo Serizawa: Kei Sato

Isami Kondo: Tadao Nakamura

Director: Kihachi Okamoto

Screenplay: Shinobu Hashimoto

Based on a novel by Kaizan Nakazoto

Cinematography: Hiroshi Murai

Art direction: Takashi Matsuyama

Film editing: Yoshitami Kuroiwa

Music: Masaru Sato

One of the joys of my pilgrimage through film history has been the discovery of great actors who aren't exactly household names in the United States. One of the best of them is Tatsuya Nakadai, who threw himself into roles with such commitment that it's almost a surprise to realize that he's still alive: He's 84 and still making movies. Even with the presence of the charismatic -- and, in the West, better-known -- Toshiro Mifune in the cast, Nakadai carries The Sword of Doom on his considerable shoulders, playing Ryunosuke, a psychotic samurai, with frightening conviction. In his first appearance, his face is partly hidden by the latticework of a hat, but his eyes burn brightly through the shadowing. He calmly murders an old man whose granddaughter has gone to fetch water. Granted, the old man is praying for death, but an easy one, not the blow of the titular sword. By the end of the film the madness that glitters in Ryunosuke's eyes has been responsible for countless deaths, and it flares up in a cataclysmic ending in which he slashes out at the ghosts he sees behind the bamboo shades of a brothel and eventually at the assassins who come for him. Nakadai does something extraordinary with his body in this final sequence: As Ryunosuke's mind comes unhinged, so does his body, killing in a kind of Totentanz that looks spasmodic but never loses its lethal precision. And there the film ends, on a freeze frame of Nakadai's face and its glittering eyes. The Sword of Doom was meant to have sequels, but they were never made. Yet although we never learn what happens to several other characters whose subplots have centered on Ryunosuke, or indeed whether he survived this orgy of blood, it doesn't really matter much. It's almost enough to have watched Nakadai in performance.

Wednesday, August 2, 2017

Conflagration (Kon Ichikawa, 1958)

|

| Tatsuya Nakadai and Raizo Ichikawa in Conflagration |

Tokari: Tatsuya Nakadai

Tayama Dosen: Ganjiro Nakamura

Tsurukawa: Yoichi Funaki

Goichi's Mother: Tanie Kitabayashi

Goichi's Father: Jun Hamamura

Director: Kon Ichikawa

Screenplay: Keiji Hasebe, Kon Ichikawa, Notto Wada

Based on a novel by Yukio Mishima

Cinematography: Kazuo Miyagawa

Music: Toshiro Mayuzumi

I haven't read the Yukio Mishima novel, The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, on which Conflagration is based, but the film has the earmarks of an adaptation from a novel, including incidents, such as Goichi's vandalizing the sword of a naval cadet who mocked him, and such secondary characters as Tsurukawa, the fellow acolyte who befriends him, whose treatment feels truncated, as if their narrative and symbolic weight was greater in the book than Kon Ichikawa was able to give them in the film. But the fine performances of Raizo Ichikawa, Ganjiro Nakamura, and Tatsuya Nakadai help Conflagration succeed on its own. Ichikawa plays a young Buddhist acolyte, Goichi, whose stammer has made him an outcast, and whose troubled childhood only worsens his sense of alienation. Nakamura plays the head priest at a temple, who studied with Goichi's father and takes the young man in out of a sense of duty, eventually paying his way to the university. There, Goichi meets another outcast, Tokari, whose deformed leg has caused him to become bitter and cynical. Although Goichi retains his shyness and naïveté, the two bond as outcasts, with Tokari's darkly rebellious philosophy eventually infecting the young acolyte, provoking him to the destructive act that gives the film its title. Nakadai's intensity in the role gives the sometimes plodding narrative, with its flashbacks within flashbacks, a needed jolt.

Watched on Turner Classic Movies

Monday, July 31, 2017

Odd Obsession (Kon Ichikawa, 1959)

|

| Tatsuya Nakadai in Odd Obsession |

Kenji Kenmochi: Ganjiro Nakamura

Toshiko Kenmochi: Junko Kano

Kimura: Tatsuya Nakadai

Hana: Tanie Kitabayashi

Masseur: Ichiro Sugai

Dr. Kodama: Mantaro Ushio

Dr. Soma: Jun Hamamura

Director: Kon Ichikawa

Screenplay: Keiji Hasebe, Kon Ichikawa, Notto Wada

Based on a novel by Jun'ichiro Tanizaki

Cinematography: Kazuo Miyagawa

Music: Yasushi Akutagawa

As with so many foreign-language films, the English title Odd Obsession seems to miss the mark a little, but the Japanese title, Kagi, which means "The Key," also seems a little off-target, even though it was taken from the novel on which the film was based. If I were retitling it, I'd call the film something like "The Jealousy Cure," which is not only in keeping with the plot but is also supported by the way the film opens, as if presenting a case study: We see a man in a physician's white coat standing before an anatomy chart, speaking directly at the camera. He describes the various effects of aging on the body before turning away to enter the action of the scene. We learn that he is Kimura, an intern in the clinic of Dr. Soma, who is treating a post-middle-aged man, Kenji Kenmochi, for sexual dysfunction. The doctor advises Kenji that the injections he has been giving him are probably ineffective, and that he should try to find other ways of dealing with the problem. Kimura has also been dating Kenji's daughter, Toshiko, and he has let slip to her that her father is seeing Dr. Soma. She passes the information along to her mother, Ikuko, whom we then see visiting Dr. Soma to find out if there is something she can do for her husband. It's an awkward encounter: Ikuko is rather embarrassed by the subject of their sex life, but she resolves to do what she can to help. Kenji then discovers that his libido is stirred by the thought of anyone having sex with his much younger wife, and when Kimura comes to dinner, Kenji begins to plot ways of bringing his wife and the young and handsome intern together. As Kimura and Ikuko begin an affair -- the key from the Japanese title is the one she gives Kimura to the back gate -- Kenji's sex drive reawakens, with the added consequence of dangerously elevating his blood pressure. Odd Obsession is not so much a case study, however, as an ironic dark comedy, one in which the follies of the various characters lead to what might be a tragic conclusion if viewed from another angle than the one Ichikawa chooses. It's also a showcase for the versatility of Tatsuya Nakadai and Michiko Kyo, who reteamed seven years later for the more serious The Face of Another (Hiroshi Teshigahara, 1966). I think Ichikawa is a little too interested in "trying things out," such as the opening segue from breaking the fourth wall into starting the action of the film, or the freeze frames that interrupt the action in the opening section, tricks that don't feel consistent with the rest of Odd Obsession.

Watched on Turner Classic Movies

Saturday, November 5, 2016

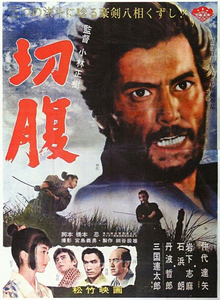

Harakiri (Masaki Kobayashi, 1962)

A study in tragic irony, Harakiri was intended as a commentary on Japan's history of hierarchical societies, from the feudal era through the Tokugawa shogunate and down to the militarism that brought the country into World War II and finally the corporate capitalism in which the salaryman becomes the latest iteration of the serf, pledging fidelity to a ruling lord. Working from a screenplay by Shinobu Hashimoto from a novel by Yasuhiko Takiguchi, director Masaki Kobayashi sets his film on a steady pace that at first feels static. There are long scenes of talk, with little moving except the camera's slow pans and zooms. But as Kobayashi's protagonist, Hanshiro Tsugumo (brilliantly played by Tatsuya Nakadai), tells his harrowing tale of loss, the film opens out into beautifully crafted scenes of action, as well as one terrifying and painful scene of cruelty, in which a man is made to commit the title's ritual disembowelment with a sword made of bamboo. Although there is an extended fight sequence in which Hanshiro takes on the entire household of the Ii clan, the true climax of the film is the duel between Hanshiro and Hikokuro Omodaka (Tetsuro Tanba), the greatest swordsman in the Ii household. Especially in this scene, the cinematography of Yoshio Miyajima makes a brilliant case for black and white film, aided by the editing of Hisashi Sagara that cuts between the dueling men and the waving grasses on the windswept hillside where the fight takes place. Harakiri is one of the best samurai films ever made, but even that observation contains its own note of irony, since Kobayashi's aim with the film is to validate his protagonist's assertion that "samurai honor is ultimately nothing but a façade."

Sunday, October 23, 2016

Kagemusha (Akira Kurosawa, 1980)

In the climactic moments of Kagemusha director Akira Kurosawa does something I don't recall seeing in any other war movie: He shows the general, Katsuyori (Ken'ichi Hagiwara) sending wave after wave of troops, first cavalry, then infantry, against the enemy, whose soldiers are concealed behind a wooden palisade, from which they can safely fire upon Katsuyori's troops. It's a suicidal attack, reminiscent of the charge of the Light Brigade, but Kurosawa chooses not to show the troops falling before the gunfire. Instead, he waits until after the battle is over and Katsuyori has lost, then pans across the fields of death to show the devastation, including some of the fallen horses struggling to get up. It's an enormously effective moment, suggestive of the dire cost of war. The film's title has been variously interpreted as "shadow warrior," "double," or decoy." In this case, he's a thief who bears a remarkable resemblance to the formidable warlord Takeda Shingen and is saved from being executed when he agrees to pretend to be Shingen. (Tatsuya Nakadai plays both roles.) This masquerade is designed to convince Shingen's enemies that he is still alive, even though Shingen dies soon after the kagemusha agrees to the ruse. The impostor proves to be surprisingly effective in the part, fooling Shingen's mistresses and winning the love of his grandson, and eventually presiding over the defeat of his enemies. But he gains the enmity of Shingen's son, Katsuyori, who not only resents seeing a thief playing his father but also holds a grudge against Shingen for having disinherited him in favor of the grandson. So when the kagemusha is exposed as a fake to the household, he is expelled from it, and Katsuyori's arrogance leads to the defeat in the Battle of Nagashino -- a historical event that took place in 1575. The poignancy of the fall of Shingen's house is reinforced at the film's end, when his kagemusha reappears in rags on the bloody battlefield, then makes a one-man charge at the palisade and is gunned down. The narrative is often a little slow but the film is pictorially superb: Yoshiro Muraki was nominated for an Oscar for art direction, although many of his designs are based on Kurosawa's own drawings and paintings, made while he was trying to arrange funding for the film. Two American admirers, Francis Ford Coppola and George Lucas, finally came through with the financial support Kurosawa needed -- they're listed as executive producers of the international version of the film, having persuaded 20th Century Fox to handle the international distribution.

Tuesday, April 5, 2016

High and Low (Akira Kurosawa, 1963)

High and Low begins surprisingly, considering that Kurosawa is known as a master director of action, with a long static sequence that takes place in one set: the living room of the home of Kingo Gondo (Toshiro Mifune), an executive with a company called National Shoe. The sequence, almost like a filmed play, depicts Gondo's meeting with the other executives of the company, who are trying to take it over, believing that the "Old Man" who runs it is out of touch with the shoe market. Gondo, however, thinks the company should focus on well-made, stylish shoes rather than the flimsy but fashionable ones the others are promoting. After the others have gone, we see that Gondo has his own plan to take over the company with a leveraged buyout -- he has mortgaged everything he has, included the opulent modern house in which the scene takes place. But suddenly he receives word that his son has been kidnapped and the ransom will take every cent that he has. Naturally, he plans to give in to the kidnappers' demands -- until he learns that they have mistakenly kidnapped the wrong child: the son of his chauffeur, Aoki (Yutaka Sada). Should he go through with his plans to ransom the boy, even though it will wipe him out? Enter the police, under the leadership of Chief Detective Tokura (Tatsuya Nakadai), and the scene becomes a complicated moral dilemma. Thus far, Kurosawa has kept things stagey, posing the group of detectives, Gondo, his wife (Kyoko Kagawa), his secretary (Tatsuya Mihashi), and the chauffeur in various permutations and combinations on the Tohoscope widescreen. But once a decision is reached -- to pay the ransom and pursue the kidnappers -- Kurosawa breaks free from the confinement of Gondo's house and gives us a thrilling manhunt, the more thrilling because of the claustrophobic opening segment. The original title in Japanese can mean "heaven and hell" as well as "high and low," and once we move away from Gondo's living room we see that his house sits high on a hill overlooking the slums where the kidnapper (Tsutomu Yamazaki) lives, and from which he can peer into Gondo's house through binoculars. We return to the police procedural world of Stray Dog (Kurosawa, 1949), where sweaty detectives track the kidnapper through busy nightclubs and the haunts of drug addicts, and Kurosawa's cameras -- under the direction of Asakazu Nakai and Takao Saito -- give us every sordid glimpse. It's a skillful thriller, based on one of Evan Hunter's novels written under the "Ed McBain" pseudonym, done with a masterly hand. And while it's not one of Kurosawa's greater films, it has unexpected moral depth, enhanced by fine performances, including a restrained one by Mifune -- this time, the freakout scene goes to Yamazaki's kidnapper.

Tuesday, September 29, 2015

The Face of Another (Hiroshi Teshigahara, 1966)

I haven't read the novel by Kobo Abe on which the film is based, but I suspect that adherence to the source (Abe also wrote the screenplay) weakens the film, which dwells heavily on ideas about identity and morality that are more efficiently explored in literature than in cinema. The central narrative deals with Okuyama (Tatsuya Nakadai) who, having been disfigured in an industrial accident, sees a psychiatrist (Mikijiro Hira) who devises an experimental mask that gives Okuyama an entirely new identity. Wearing the mask, Okuyama seduces his own wife (Machiko Kyo), who tells him that she knew who he was all along and assumed that he was trying to revive their marriage, which had been troubled since his accident. She is enraged when she learns that he was in fact testing her fidelity. But there is a secondary narrative about a beautiful young woman (Miki Irie) who bears scars along one side of her face that, it is suggested, are the result of exposure to radiation from the Nagasaki atomic bomb. In the novel, this story comes from a film seen by the characters in the main story, but Teshigahara withholds this explanation for its inclusion in the film without apparent connection to Okuyama's story. I'm not troubled by the disjunction this creates in the film, because Teshigahara and production designer Masao Yamazaki have developed a coherent symbolic style that creates an appropriate air of mystery throughout The Face of Another. The weakness lies, I think, in the dialogue, especially in the too didactic exchanges between Okuyama and the psychiatrist about the limits and potential of a mutating identity. Nevertheless, it's a fascinating, flawed film, more disturbing than most outright "horror" movies.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)