|

| Alice Guy |

A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Saturday, October 17, 2015

Alice Guy-Blaché

Friday, October 16, 2015

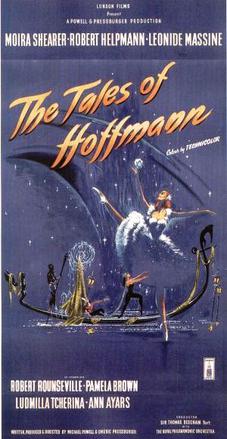

The Tales of Hoffmann (Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, 1951)

Opera and film are two well-nigh incompatible media, with different ways of creating characters, evoking mood, and telling stories. The handful of good opera films are those that find ways of replicating the operatic experience within a cinematic framework, the way Ingmar Bergman does in his film of Mozart's The Magic Flute (1975), which takes liberties with the original libretto and casts the action in a theatrical setting. The Powell-Pressburger Hoffmann also tinkers with the libretto, and with perhaps somewhat more justification: Offenbach didn't live to see his opera performed, and it exists in several variants. Opera companies rearrange and cut its various parts, and even interpolate music from other works by Offenbach. Like The Magic Flute, Hoffmann has fantasy elements that lend themselves to the special-effects treatment available to the movies, and Powell and Pressburger took full advantage. It is usually thought of as a companion piece to their film The Red Shoes (1948), in large part because it used many of the stars of that earlier film, including Moira Shearer, Robert Helpmann, Léonide Massine, and Ludmilla Tcherina, as well as production designer Hein Heckroth. The opera is sung in English, though the only singers who actually appear on screen are Robert Rounseville as Hoffmann and Ann Ayars as Antonia. Unfortunately, some of the singers whose voices are used aren't quite up to the task: Dorothy Bond sings both Olympia and Giulietta, and the difficult coloratura of the former role exposes a somewhat acidulous part of her voice. Bruce Dargavel takes on all four of the bass-baritone villains played on-screen by Helpmann, but his big aria, known as "Scintille, diamant" in the French version, lies uncomfortably beyond both ends of his range. Rounseville, an American tenor, comes off best: He has excellent diction, perhaps because he spent much of his career in musical theater rather than opera -- though he originated the part of Tom Rakewell in Stravinsky's The Rake's Progress in 1951. He is also well-known for his performance in the title role of Leonard Bernstein's Candide in the original Broadway production in 1956. It has to be said that the film is overlong and maybe over-designed, and that it sort of goes downhill after the Olympia section, in which Heckroth's imagination runs wild.

Thursday, October 15, 2015

A Matter of Life and Death (Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, 1946)

|

| David Niven and Marius Goring in A Matter of Life and Death |

Peter D. Carter: David Niven

June: Kim Hunter

Bob Trubshaw: Robert Coote

An Angel: Kathleen Byron

An English Pilot: Richard Attenborough

An American Pilot: Bonar Colleano

Chief Recorder: Joan Maude

Conductor 71: Marius Goring

Dr. Frank Reeves: Roger Livesey

Abraham Farlan: Raymond Massey

Director: Michael Powell, Emeric Pressburger

Screenplay: Michael Powell, Emeric Pressburger

Cinematography: Jack Cardiff

Production design: Alfred Junge

Fantasy, especially in British hands, can easily go twee, and though Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger had surer hands than most, A Matter of Life and Death (released in the United States as Stairway to Heaven, long before Led Zeppelin) still manages occasionally to tip over toward whimsy. There is, for example, the symbolism-freighted naked boy playing a flute while herding goats, the doctor's rooftop camera obscura from which he spies on the villagers, and the production of A Midsummer Night's Dream being rehearsed by recovering British airmen. And there's Marius Goring's simpering Frenchman, carrying on as no French aristocrat, even one guillotined during the Reign of Terror, ever did. Many find this hodgepodge delicious, and A Matter of Life and Death is still one of the most beloved of British movies, at least in Britain. I happen to be among those who find it a bit too much, but I can readily appreciate many things about it, including Jack Cardiff's Technicolor cinematography (Earth is color, Heaven black and white, a clever switch on the Kansas/Oz twist in the 1939 The Wizard of Oz) and Alfred Junge's production design. On the whole, it seems to me too heavily freighted with message -- Love Conquers Even Death -- to be successful, but it must have been a soothing message to a world recovering from a war.

Wednesday, October 14, 2015

The Confession (Costa-Gavras, 1970)

Ideologies are only as workable as the people who believe in them, which given the human drive toward power isn't very much. Costa-Gavras's film hasn't really dated much since its release 45 years ago. We are still faced with ideologues whose sole aim is to increase their own power in the name of some group or faction -- witness the current disarray of the Republican Party caused by the recalcitrance of the Tea Party faction in Congress. Which is not to say that the purge of John Boehner is anything as grave as the purges in the communist party in the Soviet Union under Stalin in the 1930s and in Czechoslovakia under Stalinist puppets in the 1950s. Yves Montand plays Gérard, a Czech communist official, based on a real figure, Artur London, who was accused of being a Trotskyite and a Titoist and of collaborating with American spies. He resisted torturous interrogation as long as possible before confessing. Sentenced to life imprisonment, he was released after serving several years in prison. The film ends with Gérard, still a disillusioned but hopeful communist, witnessing the 1968 Soviet crackdown against the "Prague Spring" reformists. It's an overlong but often effective movie, with fine performances by Montand, Simone Signoret as his wife, and Gabriele Ferzetti as the interrogator Kohoutek, a former Gestapo agent recruited by the communists to crack the people they want to purge.

Tuesday, October 13, 2015

A Lon Chaney Double Feature

He Who Gets Slapped, Victor Sjöström, 1924

The more I see of the young Norma Shearer, the more I like her. I recently watched The Student Prince in Old Heidelberg (Ernst Lubitsch, 1927), in which she's paired with Ramon Novarro, and was struck by how fresh and natural she was as an actress, and the same holds true in He Who Gets Slapped, where her love interest is John Gilbert. Both movies are silents, of course. It was only after the advent of sound that her husband, MGM's creative director Irving G. Thalberg, decided to make her into a great lady, the cinematic equivalent of Katharine Cornell, putting her into remakes of Broadway hits like The Barretts of Wimpole Street (Sidney Franklin, 1934), which had starred Cornell, or Strange Interlude (Robert Z. Leonard, 1932), which had featured another theatrical diva, Lynn Fontanne. She was also miscast as Juliet in Romeo and Juliet (George Cukor, 1936), a role that, at 34, she was much too old to play. She is barely in her 20s in He Who Gets Slapped, however, and she's delightful. This is not a film for coulrophobes (people with a fear of clowns), however. It's crawling with them, performing antics that are supposed to be, to judge from the hilarity they induce in the audiences shown in the film, side-splittingly funny. The film is based on the highly dubious premise that watching someone get slapped repeatedly is one of the funniest things ever. There may be people who think so -- to judge from the perennial popularity of the Three Stooges -- but I'm not one of them. The whole movie is an artificial concoction, anyway, and only the brilliance of Lon Chaney gives it some grounding in real-life feeling. It was one of the films that launched the MGM studios on the road to Hollywood dominance, and the first one to feature Leo the Lion in the credits.

Laugh, Clown, Laugh, Herbert Brenon, 1928

This is a grand showcase for Chaney, whose reputation as the man of a thousand faces was somewhat misleading. Chaney had one well-worn face that, no matter how much he distorted or disguised it, shone through. Here he's given an opportunity to perform without disguise through much of the film, and the range of expressions available to him is astonishing. The leading lady is 14-year-old Loretta Young. That she often looks her age is one of the more disturbing things about the film, in which she's supposed to be in love with both Chaney, who was 45, and the improbably pretty Nils Asther, who was 31. The cinematography is by James Wong Howe. Laugh, Clown, Laugh was eligible for Oscar nominations in the first year of the Academy Awards, and Chaney should have received one. The closest the film came to an award was the one that Joseph Farnham received for title writing (the one and only time the award was presented). But Farnham's award was for the body of his work over the nomination period, and not for a particular film.

Monday, October 12, 2015

House (Nobuhiko Obayashi, 1977)

This manic Japanese horror film has achieved something of a cult status. It was the feature film debut of its director, Obayashi, who began his career as a director of TV commercials, which shows in the film's continued barrage of brightly colored images and in the loud (and banal) pop music soundtrack. The story deals with a gaggle of Japanese schoolgirls (with nicknames that translate as "Gorgeous," "Fantasy," "Kung Fu," "Melody," "Prof," "Sweet," and "Mac") who find themselves trapped in a haunted house. They do a lot of running, yelling, giggling, screaming, and dying -- one of them is literally eaten by a grand piano. Ultimately, the film had a huge impact on music videos, but it remains a one of a kind movie experience -- for which some of us remain thankful while others of us relish yet another instance of the unfettered imagination of a Japanese artist. In this case, the imagination was not just that of the director but also of his pre-teen daughter, whose ideas about things that frighten children were worked into the screenplay. A great deal of credit (or blame, if you will) goes to production designer Kazuo Satsuya and cinematographer Yoshitaka Sakamoto.

Links:

House,

Kazuo Satsuya,

movies,

Nobuhiko Obayashi,

Yoshitaka Sakamoto

Sunday, October 11, 2015

Au Hasard Balthazar (Robert Bresson, 1966)

|

| Anne Wiazemsky in Au Hasard Balthazar |

Jacques: Walter Green

Gérard: François Lafarge

Marie's Father: Philippe Asselin

Marie's Mother: Nathalie Joyaut

Arnold: Jean-Claude Guilbert

Grain Dealer: Pierre Klossowski

Priest: Jean-Joel Barbier

Baker: François Sullerot

Baker's Wife: Marie-Claire Fremont

Gendarme: Jacques Sorbets

Attorney: Jean Rémignard

Director: Robert Bresson

Screenplay: Robert Bresson

Cinematography: Ghislain Cloquet

In his book Watching Them Be, James Harvey calls Au Hasard Balthazar "probably the greatest movie I've ever seen," and goes on to quote a number of others, including Jean-Luc Godard, who pretty much agree with him. I can't deny the movie's excellence, though I wouldn't quite go as far as Harvey does. It's a film that will try your patience unless you're willing to take Bresson on his own terms, which means not spelling anything out explicitly about his characters and their relationships. You're left to surmise a great deal about what they're doing and why. In fact, the only character in the film who gets a more or less fully fleshed-out story line is Balthazar himself, and he's a donkey. As usual, the performers are people we've never seen before on screen, and as usual with Bresson, that works out well, especially in the case of Anne Wiazemsky, who plays Marie. Only 19 when she made the film, she brings a freshness and vulnerability to her role that radiates through the deadpan non-acting that Bresson imposed on his performers. (The following year, she made La Chinoise with Godard -- which may help explain the extent of his enthusiasm for Balthazar -- and became his second wife after his divorce from Anna Karina.) I happen to be somewhat averse to films that center on animals, particularly if they carry the symbolic freight that Balthazar (whom one character refers to as "a saint") does, but even I couldn't help being touched by his story. This was Bresson's first film with Ghislain Cloquet as cinematographer, and the contrast with his previous film, The Trial of Joan of Arc (1962), shot by his longtime director of photography, Léonce-Henri Burel, is startling. Burel tended to follow Bresson's lead in providing austere images for austere stories, whereas Cloquet brings a romantic edge to his work. I think it only emphasizes the purity of Bresson's intentions.

Saturday, October 10, 2015

The Trial of Joan of Arc (Robert Bresson, 1962)

There are two great Joan of Arc films: The other one is Carl Theodor Dreyer's The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928). But comparing them is tricky: Dreyer's film was made in a different medium. Silent movies are not just movies without sound: They necessitate entirely different narrative techniques. Dreyer let the stunning quality of his images of the suffering Joan and the cruel and often grotesque interrogators and the crowd at her immolation do much of the business of characterizing and story-telling. According to an admirer of Bresson's, screenwriter-director Paul Schrader, Bresson disliked this about Dreyer's film, and it shows in the deliberate blandness of face and image in The Trial of Joan of Arc. The settings and costumes are generic and undistinguished, and they are lighted flatly, giving the film the banal look of the era's television dramas. As usual, Bresson has chosen unknown or non-professional actors, starting with his Joan, Florence Carrez. (Carrez was her mother's surname; she later took her father's surname, becoming Florence Delay, the name under which she became a successful novelist, playwright, and actress.) Compared to Renée Falconetti's magnificently haunting Joan in Dreyer's film, Carrez's performance is almost deadpan: She unemotionally responds to even the most provocative of her judges' questions, which Bresson took verbatim from the transcripts of the trial. On the whole, I think Bresson's austere style serves the material: When Carrez sheds a tear or even slightly raises her voice, it makes an emotional impact. By withholding so much dramatic visual information throughout the film, Bresson makes a few incidental moments the more powerful, as when we see a member of the crowd stick out a foot to trip Joan on the way to the stake, or when, as she is ascending the steps to the pyre, a small dog comes out of the crowd and stares up at her. On the whole, I prefer Dreyer's film, but I'm glad to have Bresson's as a contrast.

Friday, October 9, 2015

Pickpocket (Robert Bresson, 1959)

Maybe it's Bresson fatigue after watching three of his films in as many days (thanks to TCM's programming them in a block), but I found Pickpocket less satisfying than Diary of a Country Priest or A Man Escaped. What it does have going for it is a compelling central performance by another Bressonian unknown, Martin LaSalle, as Michel, the titular thief. LaSalle has the haunted look of the young Henry Fonda or Montgomery Clift -- a look, incidentally, that Alfred Hitchcock used to great effect by featuring those actors in two of his lesser-known films, Fonda in The Wrong Man (1956) and Clift in I Confess (1953). Pickpocket also contains a justly celebrated sequence demonstrating the team of thieves at work, a showcase for the work of Bresson's editor, Raymond Lamy. I think my mild dissatisfaction lies in Bresson's imposing his material on the structure of Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment. Like Raskolnikov, Michel lives in a cramped little garret room, meditates on the potential for a man of superior intellect to move beyond good and evil, commits a crime (though picking pockets is a good deal less evil than murdering an old woman) from which he refuses to benefit materially, gets caught, and is redeemed by his love for a "fallen woman," Jeanne (Marika Green), the film's equivalent to Dostoevsky's Sonya. The effect of all this is to make me wish that Bresson had simply decided to film Crime and Punishment. Lurking in the background as well are the existentialist novels of Camus and Sartre, which were much in vogue at the time.

Wednesday, October 7, 2015

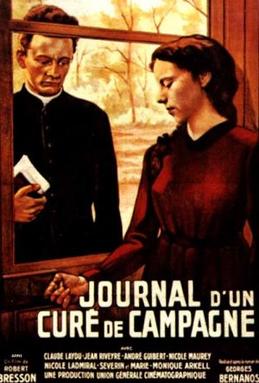

Diary of a Country Priest (Robert Bresson, 1951)

Of all the celebrated masterworks of film, Bresson's Diary of a Country Priest may be the most uncompromising in making the case for cinema as an artistic medium on the same level as literature and music. In comparison, what is Citizen Kane but a rather blobby melodrama about the rise and fall of a newspaper tycoon? Even the best of Hitchcock's oeuvre -- in which I would include Notorious (1946), Rear Window (1954), and North by Northwest (1959), while others would cite Vertigo (1958) and Psycho (1960) -- is little more than crafty embroidery on the thriller genre. The highest-praised directors, from Ford, Hawks, and Kurosawa to Godard, Kubrick, and Scorsese, never seem to stray far from the themes and tropes of popular culture. Even a film like Ozu's Tokyo Story (1953) falls back on sentiment as a way of engaging its audience. But Bresson strives for such a purity of character and narrative, down to the refusal to use well-known professional actors, and such a relentless intellectualizing, that you can't help comparing his film favorably to the great works of Flaubert or Dostoevsky. Having said that, I must admit that it's a work much easier to admire than to love, especially if, like me, you have no deep emotional or intellectual connection to religion -- or even an outright hostility to it. Does the suffering of the sickly young priest beautifully played by Claude Laydu really result in the kind of transcendence the film posits? Are the questions of grace and redemption real, or merely the product of an ideology out of tune with actual human experience? What explains the hostility he encounters in the village he tries to serve: the work of the devil or the bleakness of provincial existence? On the other hand, just asking those questions serves to point out how richly condensed is Bresson's drama of ideas. I love the movies I've cited above as somehow lacking in the intellectual seriousness of Bresson's film, but there's room in the pantheon for both kinds of film.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)