A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Thursday, March 3, 2016

The Southerner (Jean Renoir, 1945)

The Southerner is perhaps the best of the films Renoir made during his wartime exile in the United States, which is not to say that it ranks with his French masterpieces that include Grand Illusion (1937), La Bête Humaine (1938), or Rules of the Game (1939). It does, however, stand up well against the better American films of 1945, such as Mildred Pierce (Michael Curtiz), Spellbound (Alfred Hitchcock), or Leave Her to Heaven (John M. Stahl). It also earned him his only Oscar nomination as director: He lost to Billy Wilder for The Lost Weekend, but he was presented an honorary Oscar in 1975. The film was also nominated for sound (Jack Whitney) and music score (Werner Janssen). The Southerner feels less authentic than it might: Renoir was unable to overcome the Hollywood desire for gloss, so Betty Field looks awfully healthy and well-coiffed for the wife of a hard-scrabble cotton farmer whose family lives in a shack with no running water and whose youngest child almost dies of "spring sickness" -- a form of pellagra caused by malnutrition. Zachary Scott is a little more credible as her determined husband, Sam Tucker, a cotton picker who decides to start farming on his own. The role is a sharp contrast to his performance the same year in Mildred Pierce, in which he's a slick con man -- the kind of role he found himself playing more often. The cast also includes Beulah Bondi as Sam Tucker's grandmother, J. Carrol Naish as the Tuckers' stingy neighbor, and Norman Lloyd as the neighbor's nephew and man-of-all-work, who tries to drive the Tuckers off their land. Renoir is credited with the screenplay along with Hugo Butler, who did the adaptation of a novel by George Sessions Perry, but it was also worked on by an uncredited William Faulkner and Nunnally Johnson.

Wednesday, March 2, 2016

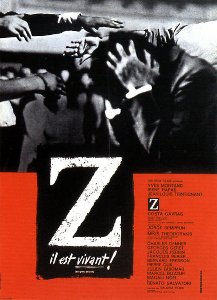

Z (Costa-Gavras, 1969)

Watching Costa-Gavras's great political thriller on a night when Donald Trump was raking in votes in the Republican primaries was unsettling. But then it was an unsettling film to watch in 1969, the year after Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. were assassinated, the police clashed with demonstrators at the Democratic convention in Chicago, and Richard Nixon was elected president. What made it unsettling this time was the way the film shows the destructive collaboration of ideologues, buffoons, and thugs. It's a more grimly funny movie than I remembered, particularly in the portrayal of the general in charge of the police, who as played by Pierre Dux is both ideologue and buffoon. There is buffoonery also among the thugs, and Costa-Gavras has fun mocking the conspirators who, once they angrily leave the room in which they've been indicted, each try to open a locked door. But we mock them in vain. For while the efforts of the prosecutor played beautifully by Jean-Louis Trintignant are heroic and Costa-Gavras and screenwriter Jorge Semprún make us expect justice to prevail, it doesn't. The story is that of the assassination of Greek opposition politician Grigoris Lambrakis in 1963 and the subsequent investigation that brought a glimmer of hope to the country only to be squelched by the military coup of 1967. However, the film is set in no specific country -- it was filmed in Algeria -- and only an opening "disclaimer" that parodies the usual assertion about any resemblance to persons living or dead dares to say that the resemblances in the film are entirely intentional. Costa-Gavras and Semprún were political exiles from, respectively, Greece and Spain. The composer Mikis Theodorakis had been arrested and his music was banned in Greece; he gave Costa-Gavras permission to use existing compositions for the film score. But the decision to set the film in no particular place only strengthened its ability to reach out and make its story meaningful beyond a specific place and time. Although Yves Montand and Irene Papas get top billing as the assassinated politician and his wife, Montand's role is comparatively small and Papas's is virtually a cameo. The movie is mostly carried by Trintignant and by Jacques Perrin, one of its producers who also plays a very aggressive investigative journalist, and a capable supporting cast. It won Oscars as the best foreign-language film and for Françoise Bonnot's film editing. It was also the first film to be nominated in the best picture category, and picked up nominations for best director and best adapted screenplay, but lost in those categories to Midnight Cowboy and its director, John Schlesinger, and screenwriter, Waldo Salt.

Tuesday, March 1, 2016

Pride (Matthew Warchus, 2014)

The success of The Full Monty (Peter Cattaneo, 1997), a movie about unemployed steelworkers who become male strippers, seems to have inspired a new genre of feel-good movies about the struggles of the British working class. And Margaret Thatcher's union-breaking efforts during the 1984 coal-miners' strike has become the nexus for a series of films in the same spirit. The year before The Full Monty, there was Brassed Off (Mark Herman, 1996), about how the brass band staffed by unemployed coal miners helped raise spirits after their pit was closed. There was Billy Elliot (Stephen Daldry, 2000), about a striking miner's son who wants to become a ballet dancer. Like The Full Monty, it became a hit stage musical. Unfortunately, once you have a string of movies like these, you also have a formula to follow, which Stephen Beresford's screenplay for Pride, in which a group of gays and lesbians in London decide to raise funds to support striking Welsh miners, does almost to the letter. It's based on a true story, and the results are amusing and heart-warming, but a feeling of déjà vu works to prevent your feeling that you've seen anything fresh and surprising. What it has going for it is a beautifully committed cast, with some familiar old pros -- Bill Nighy, Imelda Staunton, Andrew Scott, and Dominic West -- and a few fine newcomers, particularly Ben Schnetzer, an American actor who launched his career in Britain. (An interesting reversal, considering the number of Brits, including West in The Wire and The Affair, along with Andrew Lincoln in The Walking Dead, Matthew Rhys in The Americans, and Hugh Dancy in Hannibal, who have found their careers flourishing in American television.) The film capitalizes on anti-Thatcher sentiments while downplaying the contemporaneous arrival of the AIDS crisis. There is a scene in which the group's leader, Mark Ashton (Schnetzer), encounters a former lover (a cameo by Russell Tovey) who is obviously ill, and a revelation that Jonathan Blake (West) was diagnosed with the disease several years earlier, but these are incidental to the main plot. The movie manages to avoid spoiling the feel-good mood by revealing only in the credits sequence that Ashton died at the age of 26 in 1987; Blake, however, is still alive.

Monday, February 29, 2016

Clouds of Sils Maria (Olivier Assayas, 2014)

|

| Kristen Stewart and Juliette Binoche in Clouds of Sils Maria |

Valentine: Kristen Stewart

Jo-Ann Ellis: Chloë Grace Moretz

Klaus Diesterweg: Lars Eidinger

Christopher Giles: Johnny Flynn

Rosa Melchior: Angela Winkler

Henryk Wald: Hanns Zischler

Director: Olivier Assayas

Screenplay: Olivier Assayas

Cinematography: Yorick Le Saux

Production design: François-Renaud Labarthe

Film editing: Marion Monnier

Olivier Assayas's Clouds of Sils Maria demands almost as much attention after you've finished it as it did while you were watching/reading it. The set-up is this: An actress, Maria Enders, is asked to perform in a revival of the play that made her famous when she was only 18. Now that she's in her 40s, however, she will play the older woman who has a relationship with the character she earlier played. She accepts reluctantly, and then wants to back out when she finds that the younger actress, Jo-Ann Ellis, who has been cast in her original role is a Hollywood star best known not only for working in sci-fi blockbusters but also for her off-screen affairs that draw the attention of the paparazzi and Internet gossip sites. However, Maria's personal assistant, Valentine, thinks Jo-Ann is a good actress who has been exploited by the media, and persuades Maria to take the role. Maria and Valentine retreat to the home of the play's author, who has recently died, in Sils Maria, a Swiss village, where Valentine helps Maria learn her lines. As the film progresses, the lines of the play echo not only Maria's own feelings about growing older, but also the somewhat ambiguous relationship between Maria and Valentine. Indeed, it's often not entirely clear whether actress and assistant are reciting the lines of the play or are voicing their own feelings for each other. And then the casting of the film brings out another layer of meaning: Stewart is best-known for the Twilight movies, precisely the kind of Hollywood film that Maria turns up her nose at when she first hears about Jo-Ann's career. Assayas, who also wrote the screenplay, deftly juggles all these layers of art and reality, but the film would be nothing without Stewart's superb performance, which won her the César Award in France as well as the best supporting actress awards from the New York Film Critics Circle and the National Society of Film Critics. There are those who think the film is more talk than substance and that it feels like a "high-concept" product: Persona (Ingmar Bergman, 1966) meets All About Eve (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1950), perhaps. But seeing Stewart interact with Binoche more than justifies it for me.

Sunday, February 28, 2016

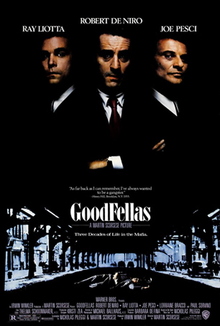

GoodFellas (Martin Scorsese, 1990)

Considering that it's Oscar night, I suppose I need to observe that 25 years ago tonight, the best picture and best director Oscars went to Dances With Wolves and Kevin Costner. For many this is yet another example of a gaffe by the Academy. I actually remember enjoying Dances With Wolves a great deal, though it has been years since I saw it. I liked Costner's and Mary McDonnell's performances in the movie, appreciated the attempt to see things from the point of view of Native Americans, and found the buffalo stampede thrilling. But I haven't seen it again for many years, and don't really have much interest in doing so: There are other equally enjoyable movies to watch instead. There are people who say that the real test of a movie is whether you want to see it again and again, because each time you do, you either see it differently or get a sense of why you liked it the first time. In the latter case, there's a great pleasure in hearing the dialogue in a movie like Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1943) fall into its accustomed place each time you revisit it. But GoodFellas seems to me to fill both categories: You anticipate the "What do you mean, I'm funny?" exchange between Tommy (Joe Pesci) and Henry Hill (Ray Liotta), while at the same time you see something new each time in the way scenes are staged by Scorsese, shot by Michael Ballhaus, or edited by Thelma Schoonmaker. I will have to say that the Academy's choice this time doesn't seem so egregious to me as does, say, its choice of Ordinary People (Robert Redford, 1980) over Raging Bull (Scorsese, 1980) does. GoodFellas is just a little too clever and showy for its own good: Consider the dazzling tracking shot as Henry and Karen (Lorraine Bracco) enter the Copacabana via the cellars and kitchens, or the fast-paced editing in the climactic scene when the paranoid Henry is dashing around town, keeping an eye on the helicopter above. On a repeat viewing, both scenes maybe draw a little more attention to film technique than is good for narrative coherence. But these are quibbles. GoodFellas won exactly one Oscar, for Joe Pesci's hair-trigger performance. Lorraine Bracco lost to Whoopi Goldberg in Ghost (Jerry Zucker), the adapted screenplay award went to Michael Blake for Dances With Wolves instead of to Nicholas Pileggi and Scorsese, and Schoonmaker lost the editing Oscar to Neil Travis for Dances. And Ray Liotta's exceptional performance went completely unnominated. But then, who knows what movie we'll be talking about 25 years from now as having unfairly lost to tonight's winner?

Saturday, February 27, 2016

The Man Who Fell to Earth (Nicolas Roeg, 1976)

This is a film that could only have been made in the mid-1970s, when people with a lot of money were looking for the Next Big Hit aimed at the youth market. And what could be better than a sci-fi film featuring a major rock star, lots of sex, and an irreverent attitude toward American corporations? Four years later, this anything-goes approach to filmmaking would expire with the colossal failure of Heaven's Gate (Michael Cimino, 1980), now known as the movie that killed United Artists. But we can see in The Man Who Fell to Earth a bit of the carelessness (some of it fueled by too-easy access to drugs) that afflicted the film industry. It is frequently brilliant but also often frequently incoherent, a movie held together by David Bowie's charisma as the alien Thomas Jerome Newton, even though Bowie later admitted that he was so high on cocaine during the filming that he didn't know what he was doing. In the film, as the titular alien, he gets hooked on gin and television, so his drug indulgence may have helped in his performance. Somehow Roeg pulled through a difficult shoot in New Mexico, and while the movie never quite succeeds as either science fiction or satire, it became a cult hit. None of the other cast members stands out as prominently as Bowie. Rip Torn doesn't put together a coherent character as Nathan Bryce, the lecherous college professor who gets hired on by the mega-corporation created by Newton so he can bring water to his dying home planet. Candy Clark plays Mary-Lou, the hotel maid who becomes Newton's lover, has some affecting moments, but it's never clear whether she is extraordinarily naive or under a kind of mind control induced by Newton. But there's an intelligence (or at least an attitude) here that makes more coherent and better polished films about alien visitors look tame and conventional.

Friday, February 26, 2016

Mannequin (Frank Borzage, 1937)

|

| Spencer Tracy and Joan Crawford in Mannequin |

John L. Hennessey: Spencer Tracy

Eddie Miller: Alan Curtis

Briggs: Ralph Morgan

Beryl: Mary Philips

Pa Cassidy: Oscar O'Shea

Mrs. Cassidy: Elisabeth Risdon

Clifford: Leo Gorcey

Director: Frank Borzage

Screenplay: Lawrence Hazard, Joseph L. Mankiewicz

Based on a story by Katharine Brush

Cinematography: George J. Folsey

Art direction: Cedric Gibbons

Film editing: Fredrick Y. Smith

Costume design: Adrian

Music: Edward Ward

Joan Crawford in her MGM prime, tough but slinky, convincing as the factory girl trudging up the stairs to the Hester Street flat she shares with her family, but also as the chorus girl, the high-fashion model, the fur-bedecked millionaire's wife. Mannequin is a very talky melodrama, but one with a kind of reassuring confidence about what it's doing, helped along by Crawford's skill and commitment as an actress. She never does anything by rote. The screenplay is by Lawrence Hazard, but anyone who knows the work of the film's producer, Joseph L. Mankiewicz, as a screenwriter can sense the uncredited contribution of the writer-director of A Letter to Three Wives (1949) and All About Eve (1950). Not that Mannequin is up to the standard of those films, but that someone connected to all three movies knows that smart talk can bring a film to life. Frank Borzage, who had won Oscars for directing the "women's pictures" 7th Heaven (1927) and Bad Girl (1931), had just the right touch for this movie. It somehow manages to overcome a lack of chemistry between its leads, Crawford and Spencer Tracy, who didn't hit it off -- she later accused him of stepping on her feet when they were dancing together and of chewing garlic before their love scenes, in addition to his typical "bad drunk" behavior -- and never worked together again. There is, however, a good performance by Alan Curtis as her sleazy first husband, a would-be fight promoter who comes up with the scheme that she should divorce him to marry Tracy's millionaire shipping magnate, then soak him of his millions. And Oscar O'Shea as her ne'er-do-well father, Elisabeth Risdon as her doormat mother, and a terrific Leo Gorcey as her wise-ass brother all make it clear that Crawford's character has no way to go but up.

Thursday, February 25, 2016

Our Dancing Daughters (Harry Beaumont, 1928)

|

| Joan Crawford in Our Dancing Daughters |

Diana (Joan Crawford) is a Good Girl who people think is a Bad Girl because she likes to dance the Charleston on tabletops. Ann (Anita Page) is a Bad Girl posing as a Good Girl to try to land a rich husband. Beatrice (Dorothy Sebastian) is a Good Girl trying to hide the fact that she used to be a Bad Girl from Norman (Nils Asther), the man she has fallen in love with. And so it goes, as Ann steals Ben (Johnny Mack Brown) away from Diana, and Beatrice confesses her past sins to Norman, who marries her but doesn't really trust her. This romantic melodrama was a big hit that established Crawford as a star. She's lively and funny and dances a mean Charleston -- a far cry from the long-suffering shoulder-padded Crawford of Mildred Pierce (Michael Curtiz, 1945) and the melodramas of her middle age, though we can see a hint of the Crawford to come when she squares off against Page, using her big eyes and lipsticked mouth as formidable weapons. The movie is semi-silent: It has a synchronized music track with some forgettable songs and occasional sound effects like the ring of a telephone and the knock on a door, and once there's a spoken line from a bandleader: "Come on, Miss Diane, strut your stuff." But most of the dialogue is confined to intertitles that tell us Diana has asked a boy to dance ("Wouldst fling a hoof with me?") or that Freddie (Edward J. Nugent) has asked Ann if she wants a drink ("Lí'l hot baby want a cool li'l sip?"). The Jazz Age was probably never like this, even at its height, which was several years earlier, but there is fun to be had here. The story, such as it is, was by Josephine Lovett, and those title cards were the work of Marian Ainslee and Ruth Cummings, who give it a mildly feminist spin: Despite the slut-shaming, the film is solidly on the side of the rights of women to have a good time. Lovett's story and George Barnes's cinematography were considered for Oscars -- there were no official nominations this year -- but lost out.

Wednesday, February 24, 2016

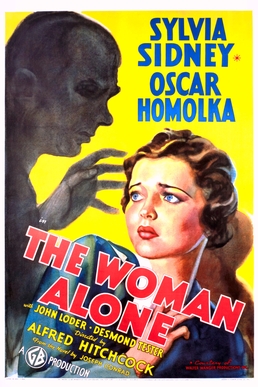

Sabotage (Alfred Hitchcock, 1936)

|

| Sabotage poster with the original title for the U.S. release |

Tuesday, February 23, 2016

The Entertainer (Tony Richardson, 1960)

Sleazy old Archie Rice was one of Laurence Olivier's theatrical triumphs, proof that a renowned classical actor, known for his Hamlet and Oedipus and Coriolanus, could take on the "kitchen-sink realism" of an Angry Young Man, John Osborne, and add glory to his already celebrated name. But the film version is an example of the difficulties that have to be overcome when a play is translated into a movie. For even though Tony Richardson, who directed the 1957 Royal Court Theatre version, also directed the film, and the play's author did the screenplay as well (in collaboration with Nigel Kneale), the movie lacks energy and direction. The play alternates between what's going on in Archie Rice's house and his performances on stage, while the film "opens up" to show the English seaside resort town where Archie's music-hall is located, and some of the events that are merely narrated in the play, such as Archie's affair with a young woman whose family he tries to persuade to back him in a new show, are dramatized in the movie. Olivier's creation of the "dead behind the eyes" Archie is superb, and his music-hall turns in the film manage to suggest that even though he was a hack as a performer Archie could have held an audience's attention, though it's clear that seeing Olivier on an actual stage would have had a stronger impact from sheer immediacy. The cast is uniformly fine: Brenda de Banzie as Archie's second wife, Roger Livesey as his father (Livesey was in fact only a year older than Olivier), Joan Plowright as his daughter, and making their film debuts, Alan Bates and Albert Finney as his sons. But in the end it's a collection of impressive performances in service of a not very involving story of a self-destructive man and his dysfunctional family.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)