A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Tuesday, May 10, 2016

Metropolis (Fritz Lang, 1927)

Metropolis strikes me as the most balletic movie ever made. I'm not referring just to Brigitte Helm's fabulous hoochie-coochie as the False Maria, which so thrills the goggling, slavering gentlemen of Metropolis, but to the fact that as one of the great silent films it brilliantly substitutes movement for the speech and song the medium denies it. In addition to Helm's terrific performance as both Marias, we also have Gustav Fröhlich's wildly over-the-top Freder, who flings himself frenziedly about the sets. We may find the performance laughable today, but it's best to watch the film with the understanding that subtlety just wouldn't work in Fritz Lang's fever-dream of a city. Certainly that's also true of the always emotive Rudolf Klein-Rogge, whose Rotwang is pretty much indistinguishable from his Dr. Mabuse. But even the stillest of the characters in the film -- Alfred Abel's Joh Frederson, Fritz Rasp's superbly creepy Thin Man -- are there to provide a sinister contrast to the hyperactivity going on around them. And then there are the crowds, a corps de ballet if ever there was one, whether stiffly marching to and from their jobs, or celebrating the fall of the Heart Machine with a riotous ring-around-the-rosy. There are times when Lang's manipulation of crowds reminds me of Busby Berkeley's. Lang's choreographic approach to the film is essential to its success as a portrayal of the subsuming of the human into the mechanical. Is there a more brilliant depiction of the alienation of work than that of the man who must shift the hands around a gigantic clock face to keep up with randomly illuminated light bulbs? Metropolis is usually cited as a triumph of design, and it probably wouldn't have the hold over us that it does without the sets of Otto Hunte, Erich Kettelhut, and Karl Vollbrecht, whose influence over our visions of the future seems indelible. Would we have the decor of the Star Wars movies or any of today's superhero epics without their work? There are those who would argue that the film is long on visual excitement but short on intellectual content -- the moral banality, that the Heart must mediate between the Head and the Hand, hardly seems to suffice as a justification for the film's Sturm und Drang -- which weakens its reputation as a masterpiece. But that seems to me to ask more of movies than they were ever designed to provide. So much in Metropolis reverberates with history -- from the French Revolution to the Bolsheviks to the Nazis -- that it's a film we can never get out of our heads, and probably shouldn't.

Monday, May 9, 2016

The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (Fritz Lang, 1933)

Lang's Dr. Mabuse the Gambler (1922) hardly needed a sequel, but the director makes it worth our while by adding sound to the concoction. Take, for example, the segue from the tick ... tick ... tick of the timer on a bomb to the chip ... chip ... chip of someone removing the shell from a soft-boiled egg. It's a witty touch that not only eases tension with laughter, but also demonstrates the prevalence of the sinister in everyday life. Hitchcock, it is often noted, learned a great deal from Lang. Mabuse (Rudolf Klein-Rogge) is more of a felt presence than a visible one in this version, confined as he is to an insane asylum where he supposedly dies, only to haunt not only the inmate Hofmeister (Karl Meixner) but also, and especially, the head of the asylum, Prof. Baum (Oscar Beregi Sr.), who is compelled to carry out Mabuse's plans for world domination. As in the 1922 film, there is a doughty policeman, Commissioner Lohmann (Otto Wernicke), who is determined to foil Mabuse's nefarious plans. Wernicke, whose character Lang brought over from M ( 1931), is not as hunky as the earlier film's von Wenk (Bernhard Goetze), so Lang and screenwriter Thea von Harbou add to the mix a young leading man, Gustav Diessl, who plays Thomas Kent, an ex-con who escapes from Mabuse's snares to aid Lohmann in trapping Baum in his efforts to fulfill Mabuse's plot. It's extremely effective suspense hokum, not raised quite to the level of art the way the 1922 film was, but still a cut above the genre. As is usually noted, this was Lang's last film in Germany. It was suppressed by the Nazis, ostensibly because it suggested that the state could be overthrown by a group of people working together, but perhaps also because of its suggestion that world domination might not be such a good thing.

Sunday, May 8, 2016

Dr. Mabuse the Gambler (Fritz Lang, 1922)

It's a four-and-a-half-hour movie, and I've seen two-hour movies that felt longer. It zips along because Fritz Lang never fails to give us something to look at and anticipate. There is, first and foremost, the hypnotic (almost literally) performance of Rudolf Klein-Rogge as Mabuse, a role that could have degenerated into mere villainous mannerisms. There is his dogged and thwarted but always charismatic opponent, von Wenk (Bernhard Goetzke), who seems on occasion to resist Mabuse's power by mere force of cheekbones. There is the extraordinary art decoration provided by Otto Hunte and Erich Kettelhut, which often gives the film its nightmare power: Consider, for example, the exceedingly odd stage decor provided for the Folies-Bergère performance by Cara Carozza (Aud Egede-Nissen), in which she contends with gigantic heads with phallic noses (or perhaps beaks), or the collection of primitive and Expressionist art belonging to the effete Count Told (Alfred Abel). The story itself, adapted from the novel by Norbert Jacques by Lang's wife-to-be Thea von Harbou, is typically melodramatic stuff about a megalomaniac psychiatrist, who uses his powers to become a master criminal. But l think it succeeds not only because it has so much to say about the period in which it was made -- i.e., "from Caligari to Hitler," as TCM's programmers would have it, following up on a documentary about Weimar Republic-era filmmakers based in part on the 1947 book by Siegfried Kracauer -- but also because of our continuing fascination with mind control. Maybe it's just because this is a presidential election year, but I'm reminded that there's a little Mabuse in everyone who seeks power. Somehow we continually lose our skepticism, born of hard experience, about the manipulators and find ourselves once again yielding to them. And somehow we usually, like von Wenk, find a way to pull ourselves back from the brink. But, as Lang himself experienced, we don't always manage to do so.

Saturday, May 7, 2016

Mr. Arkadin (Orson Welles, 1955)

|

| Michael Redgrave in Mr. Arkadin |

Guy Van Stratten: Robert Arden

Mily: Patricia Medina

Burgomil Trebitsch: Michael Redgrave

Jakob Zouk: Akim Tamiroff

Sophie: Katina Paxinou

The Professor: Mischa Auer

Thaddeus: Peter van Eyck

Raina Arkadin: Paola Mori

Baroness Nagel: Suzanne Flon

Director: Orson Welles

Screenplay: Orson Welles

Cinematography: Jean Bourgoin

Art direction: Orson Welles

Film editing: Renzo Lucidi, William Morton, Orson Welles

Music: Paul Misraki

"What if?" is the question that haunts every Orson Welles film after Citizen Kane (1941). What if Welles had had the financial, production, and distribution support for his films? Of none of them is the question more appropriate than Mr. Arkadin, which was edited by other hands than Welles's and not even shown in the United States until 1962, and at one point was said to exist in at least seven different versions. In 2006, the Criterion Collection released a three-DVD set that edited together all of the existing English-language versions of the film, following what was known of Welles's original plan, along with his comments on some of the other versions that had been released. It's probably as close as we're going to get to what the director had in mind. So what if Mr. Arkadin had been under Welles's control all along? Would we have a more coherent narrative and style? Would the protagonist, Guy Van Stratten, have been played by a more skilled actor than Robert Arden? (It's a role that would have been perfect for someone like William Holden.) Would Welles have called on the best makeup artists to provide him with a more convincing prosthetic nose and a wig and beard whose edges don't show? Would the function and the fate of Patricia Medina's character, Mily, have been clearer? And does any of this really matter? For what we have here, despite Welles's later description of the film (or its handling) as a "disaster," is one of the most fascinating works in his storied, troubled career. There are sequences that are haunting, even if their purpose in the film is unclear, such as the procession of the penitentes, who in their tall, pointed hoods look like exactly what Mily mistakes them for: "crazy ku kluxers." Or the Goyaesque masks at Arkadin's ball. Or the sequence of truly wonderful cameo performances, including a hair-netted Michael Redgrave as the junk dealer Burgomil Trebitsch, who keeps trying to sell Van Stratten a busted telescope (which he pronounces "telly-o-scope"). Or Mischa Auer as the proprietor of a flea circus. Or Katina Paxinou as a Mexican (?) woman named Sophie. And then there's one of Welles's most celebrated speeches, perhaps second only to his "cuckoo clock" monologue in The Third Man (Carol Reed, 1949), in which Arkadin tells the fable of the scorpion and the frog. Though analogues have been found in folklore around the world, this particular formulation of it seems to have been Welles's own:

This scorpion wanted to cross a river, so he asked the frog to carry him. No, said the frog, no thank you. If I let you on my back you may sting me and the sting of the scorpion is death. Now, where, asked the scorpion, is the logic in that? For scorpions always try to be logical. If I sting you, you will die. I will drown. So, the frog was convinced and allowed the scorpion on his back. But, just in the middle of the river, he felt a terrible pain and realized that, after all, the scorpion had stung him. Logic! Cried the dying frog as he started under, bearing the scorpion down with him. There is no logic in this! I know, said the scorpion, but I can't help it -- it's my character.Perhaps it was Welles's character that betrayed him into making movies that flopped but turned into classics.

Friday, May 6, 2016

Pépé le Moko (Julien Duvivier, 1937)

When Walter Wanger decided to remake Pépé le Moko in 1938 as Algiers (John Cromwell), he tried to buy up all the existing copies of the French film and destroy them. Fortunately, he didn't succeed, but it's easy to see why he made the effort: As fine an actor as Charles Boyer was, he could never capture the combination of thuggishness and charm that Jean Gabin displays in the role of Pépé, a thief living in the labyrinth of the Casbah in Algiers. It's one of the definitive film performances, an inspiration for, among many others, Humphrey Bogart's Rick in Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1943). The story, based on a novel by Henri La Barthe, who collaborated with Duvivier on the screenplay, is pure romantic hokum, but done with the kind of commitment on the part of everyone involved that raises hokum to the level of art. Gabin makes us believe that Pépé would give up the security of a life where the flics can't touch him, all out of love for the chic Gaby (Mireille Balin), the mistress of a wealthy man vacationing in Algiers. He is also drawn out of his hiding place in the Casbah by a nostalgia for Paris, which Gaby elicits from him in a memorable scene in which they recall the places they once knew. Gabin and Balin are surrounded by a marvelous supporting cast of thieves and spies and informers, including Line Noro as Pépé's Algerian mistress, Inès, and the invaluable Marcel Dalio as L'Arbi.

Thursday, May 5, 2016

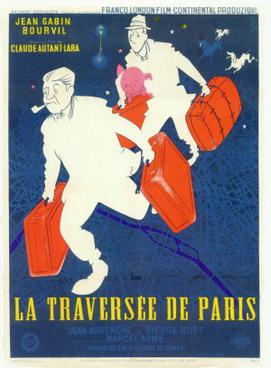

Four Bags Full (Claude Autant-Lara, 1956)

Like most movie-lovers whose knowledge of film extends beyond "Hollywood," I was familiar with Jean Gabin, especially through his work for Jean Renoir in Grand Illusion (1937), La Bête Humaine (1938), and French Cancan (1955). But although I had encountered the name, I didn't know Bourvil, celebrated in France but not so much on this side of the Atlantic. Which made it difficult for me at first to capture the tone and humor of Four Bags Full, a film also known as La Traversée de Paris, The Trip Across Paris, and Pig Across Paris. Since the film begins with newsreel footage of German troops occupying Paris in 1942, it strikes a more serious tone than it eventually takes. Marcel Martin (Bourvil) is a black market smuggler tasked with carrying meat from a pig that's slaughtered at the beginning of the movie while he plays loud music on an accordion to cover its squeals. He's responsible for transporting two suitcases filled with pork across the city to Montmartre, but when the other smuggler fails to show up, he has to accept the aid of a stranger, Grandgil (Gabin), who agrees to carry the other two valises. Grandgil, however, wants the butcher, Jambier (Louis de Funès), to pay much more than the originally agreed-upon amount for his services, and blackmails him into accepting, to the consternation of Martin. The task is perilous, given the vigilance of the French police and the German occupying troops, so the film wavers between thriller and comedy -- the latter particularly when some stray dogs pick up the scent of what's in the suitcases. The film ends up being a fascinating tale of the odd-couple relationship between Grandgil and Martin, as well as a picture of what Parisians went through during the occupation. It was controversial when it was released because it takes a warts-and-all look at black-marketeers and the Résistance, downplaying the heroism without denying the genuine risks they took. Eventually, Grandgil and Martin are caught by the Germans, but Grandgil is released because the officer in charge recognizes him as a famous artist. Martin is sent to prison, but the two are reunited after the war when Grandgil recognizes him at a train station as the porter carrying his luggage -- a rather obvious, and somewhat sour, bit of irony.

Wednesday, May 4, 2016

Wild Rose (Sun Yu, 1932)

|

| Wild Rose director Sun Yu |

|

| Wang Renmei in Wild Rose |

Tuesday, May 3, 2016

The Young Girls of Rochefort (Jacques Demy, 1967)

|

| Catherine Deneuve and Françoise Dorléac in The Young Girls of Rochefort |

Solange Garnier: Françoise Dorléac

Yvonne Garnier: Danielle Darrieux

Andy Miller: Gene Kelly

Étienne: George Chakiris

Maxence: Jacques Perrin

Simon Dame: Michel Piccoli

Bill: Grover Dale

Josette: Geneviève Thénier

Subtil Dutroux: Henri Crémieux

Director: Jacques Demy

Screenplay: Jacques Demy

Cinematography: Ghislain Cloquet

Production design: Bernard Evein

Film editing: Jean Hamon

Music: Michel Legrand

I appreciate Jacques Demy's hommage to the Hollywood musical, but I think I would have to like Michel Legrand's songs more to really enjoy The Young Girls of Rochefort. Demy's The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964) has been known to seriously divide and damage friendships, though when I last saw it I rather enjoyed its cheeky sentimentality and bright colors. Rochefort takes a similar approach to Cherbourg, setting a musical romance in a French town and filling it with wall-to-wall Legrand songs, but by doubling down on the concept -- giving us multiple romances, extending the time from Cherbourg's 91 minutes to Rochefort's more than two hours, and bringing in guest stars from American musicals -- it begins to try one's patience. Catherine Deneuve, who starred in Cherbourg, is joined by her sister, Françoise Dorléac, and the two of them have great charm, though Deneuve's delicately beautiful face is smothered under an enormous blond wig for much of the film. They are courted by Étienne and Bill, who often seem to be doing dance movements borrowed from Jerome Robbins's choreography for West Side Story (Robbins and Robert Wise, 1961), in which the actor playing Étienne, George Chakiris, appeared. (Rochefort's choreographer is Norman Maen.) But Solange winds up with an American composer, Andy Miller, while Delphine keeps missing a connection with Maxence, an artist who has painted a picture of his ideal woman who looks exactly like Delphine. Meanwhile, their mother, Yvonne, doesn't realize that her old flame (and the father of her young son), Simon Dame, has recently moved to Rochefort. (She had turned him down because she didn't want to be known as Madame Dame. No, I'm not kidding.) And so it goes. The movie is given a jolt of life by Gene Kelly's extended cameo: At 55, he's as buoyant as ever, though somewhat implausible as the 25-year-old Dorléac's love interest. He would have been better paired with Darrieux. It's a candy-box movie, but for my taste it's like someone got there first and ate the best pieces, leaving me the ones with coconut centers.

Monday, May 2, 2016

Faust (F.W. Murnau, 1926)

Sunday, May 1, 2016

Nosferatu (F.W. Murnau, 1922)

As Bram Stoker first described him, Count Dracula was by no means hideous. Creepy, yes, but with his long white mustache, his aquiline nose, and his "extraordinary pallor," he must have been at least striking to see. Most of the incarnations of Count Dracula on screen have been more or less attractive men: Bela Lugosi, Christopher Lee, Jack Palance, Frank Langella, Jonathan Rhys Meyers, among many others. And lately, since Anne Rice's novels and Buffy the Vampire Slayer's Angel (David Boreanaz) and Spike (James Marsters), the tendency has been to portray vampires as hot young dudes like the ones seen on the CW's The Vampire Diaries and The Originals. Vampires, it seems, have been getting more human. But not the very first version of Dracula portrayed on screen: With his steady glare, his beaky nose, his batlike ears, his long taloned fingers, his implacable stiff-legged gait, and his posture suggestive of someone who has been crammed for a long time into a coffin, Max Schreck's Count Orlok (the name has been changed to protect the studio, which it didn't) is decidedly non-human. He's a mutant, perhaps, or an alien. He is also not sexy, which is something of a paradox because vampirism, with its night prowling and exchange of fluids, is all about sex -- or the fear of it. And yet this is probably the greatest film version of Dracula, even allowing for the fact that it's a ripoff, designed to allow the producers Enrico Dieckmann and Albin Grau to avoid having to pay the Stoker estate for the rights. They were sued, and according to the terms of the settlement all prints of the film were supposed to be destroyed. The studio went out of business, but Nosferatu was undead -- enough copies survived that it could be pieced together for posterity. Undead, but not undated: Some of the opening scenes involving Hutter (Gustav von Wangenheim), the novel's Harker, are a bit laughable given the actor's puppyish grin, and the character of Knock (Alexander Granach), the novel's Renfield, is wildly over-the-top. But Murnau knew how to create atmosphere, and he keeps the action grounded in plausibility by using real locations and natural settings. The scene in which a long procession of coffins filled with plague victims moves down a street (actually in Lübeck) is haunting. But most of all, it's Schreck's uncanny performance that makes Nosferatu still able to stalk through dreams after more than 90 years.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)