A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Friday, June 10, 2016

No Country for Old Men (Joel Coen and Ethan Coen, 2007)

No Country is not my favorite Coen brothers film; Fargo (1996), Inside Llewyn Davis (2013), Miller's Crossing (1990), and maybe O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000) and The Big Lebowski (1998) would have to rank higher. But that only shows what an extraordinary contribution the brothers have made to motion picture history. There are those who task the Coens with too much cleverness, too much awareness of breaking or bending conventions, such as, in this film, dispatching both the protagonist and the antagonist off-screen, depriving us of the catharsis usual in such a thriller. There is, some critics argue, something chilly about the Coens, never letting us get too involved in their characters as potentially real human beings. I'd argue that engaging sympathetic identification with characters is not a sine qua non in art, and that the tendency of writers and directors to do that has led to a lot of sentimental and falsified endings. And anyway, who doesn't feel a sympathetic identification with Marge Gunderson in Fargo, or the Dude in The Big Lebowski, to name two of their greatest characters? (They also happen to be original creations of the Coens, not borrowed from a novel, as the characters in No Country are.) I haven't read the Cormac McCarthy novel, but the film strikes me as a moral fable akin to Chaucer's Pardoner's Tale, with the implacable Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem) as the Death figure stalking Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin), whose avarice -- though modified by a few virtues, such as bringing a jug of water, albeit too late, to the man he finds dying in the desert -- finally proves his undoing, despite his clever attempts to avoid his fate. We root for Moss because of our common humanity, a trait lacking in the psychotic Chigurh, but it's telling that the story is framed by the point of view of Ed Tom Bell (Tommy Lee Jones), who can only see the story as a manifestation of what is lacking in human beings. Ed Tom thinks it has something to do with the changing times, which is why there seem to be no countries for old men anymore, but I would suggest that the medieval fable analogy overrides Ed Tom's theory: Human beings have always been like this. That said, the Coens seem to be assembling a kind of American collage. One thing that No Country shares with all of the Coens' best movies is a strong sense of time and place, whether it's the frigid Minnesota of Fargo, the Greenwich Village in the '60s of Inside Llewyn Davis, the unspecified Prohibition-era city of Miller's Crossing, the Depression-era Mississippi of O Brother, or the '90s L.A. of The Big Lebowski. In this case, it's West Texas in 1980, and every note struck about place and period has a resemblance to truth, without being literal about it. As usual, the Coens' collaborators -- especially cinematographer Roger Deakins and composer Carter Burwell -- play a major role, especially Burwell's almost subliminal score.

Wednesday, June 8, 2016

Laura (Otto Preminger, 1944)

Laura is a clever spin on Pygmalion, with a Henry Higgins called Waldo Lydecker (Clifton Webb) whose protégée is an Eliza Doolittle called Laura Hunt (Gene Tierney). It's also a spin on the classical myth of Pygmalion, who fell in love with the statue of Galatea he had sculpted, bringing her to life. This Pygmalion is a detective, Mark McPherson (Dana Andrews), who falls in love with the portrait of Laura, who he thinks has been murdered, and is startled when she walks through the door, very much alive. Maybe this classical underpinning explains why Laura has become such an enduring classic, but probably it really has to do with a story so well-scripted, by Jay Dratler, Samuel Hoffenstein, and Elizabeth Reinhardt from a novel by Vera Caspary, well-acted by Webb, Tierney, and Andrews, along with Vincent Price as the decadent Shelby Carpenter and Judith Anderson as the predatory Ann Treadwell, and most of all, directed with the right attention to its slyly nasty tone by Otto Preminger, one of the most underrated of Hollywood directors of the 1940s and '50s. Like such acerbic films as The Maltese Falcon (John Huston, 1941) and All About Eve (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1950), Laura is full of characters one would be well advised to steer clear of in real life, but who make for tremendous entertainment when viewed on a screen from a safe distance. It makes a feint at a conventional happily romantic ending, with Laura supposedly going off with McPherson, but do we really believe it? Laura Hunt has shown dubious taste in men -- whom McPherson characterizes as "a remarkable collection of dopes"-- including the desiccated fop Waldo and the smarmy kept man Shelby. So it's hard to believe the social butterfly Lydecker has created is going to settle down happily with a man who, as Waldo says once, fell in love with her when she was a corpse and apparently has never had a relationship with a woman other than the "doll in Washington Heights who once got a fox fur outta" him. Laura is notable, too, for its deft evasions of the Production Code, including Laura's hinted-at out-of-wedlock liaisons, which are at the same time undercut by the suggestions that Waldo and Shelby are gay -- another Code taboo. (Shelby, for example, has an exceptional interest in women's hats, including one of Laura's and the one of Ann's that he calls "completely wonderful.") This shouldn't surprise us, as Preminger went on to be one of the most aggressive Code-breakers, challenging its sexual taboos in The Moon Is Blue (1953) and its strictures on the depiction of drug use in The Man With the Golden Arm (1955), and giving the enforcers fits with Anatomy of a Murder (1959). In addition to the contributions to Laura's classic status already mentioned, there is also the familiar score by David Raksin. (Johnny Mercer added lyrics to its main theme after the film was released, creating the song "Laura.") And Joseph LaShelle won an Oscar for the film's cinematography.

Tuesday, June 7, 2016

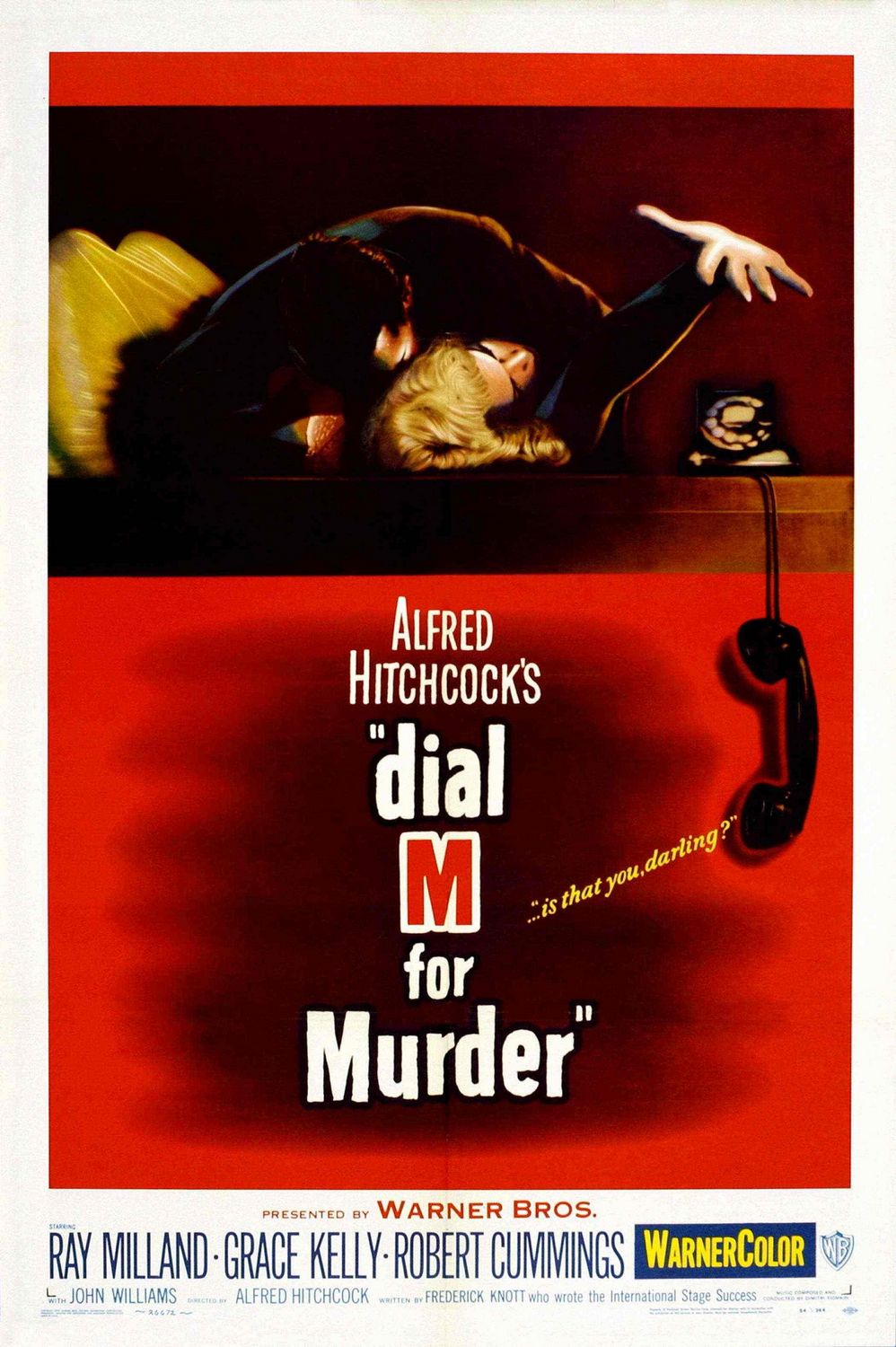

Dial M for Murder (Alfred Hitchcock, 1954)

It's a measure of how little Hollywood understood what kind of filmmaker Alfred Hitchcock was that Warner Bros. insisted he make Dial M for Murder in 3-D. The process was nearing the end of its '50s heyday, one of the several attempts by the troubled studios to draw patrons away from their TV sets and into the theaters. The 3-D films of the '50s, like the blockbusters released in the process today, were mostly filled with things being flung, poked, thrust, or shot at the audience. As Hitchcock had a reputation as a "master of suspense," perhaps the studio assumed that he'd use the process to scare people. But he never needed tricks like 3-D for that, being perfectly skilled at pacing and cutting to build tension in the audience. Dial M ended up being shown mostly in 2-D anyway, and only some very peculiar blocking and framing in its images today show the efforts Hitchcock and cinematographer Robert Burks did to accommodate the moribund process: Scenes are often filmed with table lamps prominent in the foreground, for no other reason than to emphasize the action taking place beyond them. The scene in which Swann (Anthony Dawson) attempts to murder Margot (Grace Kelly) is the only bit of action that would have benefited from the process, with Margot's hand desperately reaching toward the audience for the scissors behind her. Dial M is essentially a filmed play -- Frederick Knott adapted his own theatrical hit for the movies -- and as such relies far more on dialogue and spoken exposition for its narrative coherence. It was the first of three movies -- the other two are Rear Window (1954) and To Catch a Thief (1955) -- that Hitchcock made with Kelly, and the one that gives her least to do in the way of characterization: Mostly she just has to be a pawn moved about by her husband (Ray Milland), her lover (Robert Cummings), and the police inspector (John Williams). But she clearly defined Hitchcock's "type," already partly established in his films with Joan Fontaine and Ingrid Bergman: the so-called "cool blond." Eva Marie Saint, Kim Novak, Tippi Hedren, and Janet Leigh would attempt to fill the role afterward, but never with quite the charisma that Kelly, a limited actress but a definite "presence," achieved for him. Milland is very good as the murderous husband, and Williams is a delight as the inspector who has to puzzle out what's going on with all those door keys. The rather goofy-looking Cummings has never made sense to me as a leading man -- he almost wrecks Saboteur (1942), an otherwise well-made Hitchcock film that might be regarded as one of his best if someone other than Cummings and the bland Priscilla Lane had been cast in the leads. It's not surprising that after his performance in Dial M he went straight into television and his own sitcom.

Monday, June 6, 2016

Rebel Without a Cause (Nicholas Ray, 1955)

Rebel Without a Cause seems to me a better movie than either of the other two James Dean made: East of Eden (Elia Kazan, 1955) and Giant (George Stevens, 1956). It's less pretentious than the adaptation of John Steinbeck's attempt to retell the story of Cain and Abel in the Salinas Valley, and less bloated than the blockbuster version of Edna Ferber's novel about Texas. And Ray, a director with many personal hangups of his own, was far more in tune with Dean than either Kazan or Stevens, who were shocked by their star's eccentricities. Granted, Rebel is full of hack psychology and sociology, attributing the problems of Jim Stark (Dean), Judy (Natalie Wood), and John "Plato" Crawford (Sal Mineo) to parental inadequacy: Jim's weak father (Jim Backus) and domineering mother (Ann Doran) and paternal grandmother (Virginia Brissac), Judy's distant father (William Hopper) and mother (Rochelle Hudson), and Plato's absentee parents who have left him in care of the maid (Marietta Canty). In fact, Jim and his friends really are rebels without a cause, there being neither an efficient cause -- one that makes them do stupidly self-destructive things -- nor a final cause -- a clear purpose behind their madness. Fortunately, Ray is not as interested in explaining his characters as he is in bringing them to life. Unlike Kazan or Stevens, Ray gives his actors ample room to explore the parts they're playing. There's a loose, improvisatory quality to the scenes Dean, Wood, and Mineo play together, more suggestive of the French New Wave filmmakers than of Hollywood's tightly controlled directors. It's no surprise that both Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut were admirers of Ray's work. At the same time, though, Rebel is very much a Hollywood product, with vivid color cinematography by Ernest Haller, who had won an Oscar for his work on Gone With the Wind (Victor Fleming, 1939), and a fine score by Leonard Rosenman. Most of all, though, it has Dean, Wood, and Mineo, performers with an obvious rapport. At one point, for example, Dean puts a cigarette in his mouth backward -- filter on the outside -- and Wood reaches out and turns it around, a bit establishing their intimacy that feels so real that you wonder if it was improvised or developed in performance. (In fact, I noticed the gesture because I had just seen Billy Wilder's The Lost Weekend, made ten years earlier, in which Jane Wyman performs the same turning-the-cigarette-around action for Ray Milland several times. Cigarettes are nasty things but they make wonderful props.)

Sunday, June 5, 2016

The Lost Weekend (Billy Wilder, 1945)

If such a thing as conscience could be ascribed to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, it might be said that giving The Lost Weekend and director Billy Wilder the best picture and best director Oscars was an attempt to atone for its failure to honor Wilder's Double Indemnity with those awards the previous year. (The awards went to Leo McCarey and his saccharine Going My Way.) The Lost Weekend is not quite as enduring a film as Double Indemnity: It pulls its punches with a "hopeful" ending, though it should be clear to any intelligent viewer that Ray Milland's Don Birnam is not going to be so easily cured of his alcoholism as he and his girlfriend, Helen St. James (Jane Wyman), seem to think. But the film also lands quite a few of its punches, thanks to Milland's Oscar-winning performance and the intelligent (and also Oscar-winning) adaptation of Charles R. Jackson's novel by Wilder and co-writer Charles Brackett. For its day, still under the watchful eyes of the Paramount front office and the Production Code, The Lost Weekend seems almost unnervingly frank about the ravages of alcoholism, then usually treated more as a subject for comedy than for semi-realistic drama. The Code prevented the film from ascribing Birnam's drinking to an attempt to cope with his homosexuality, but in some respects this can be seen today as a good change made for the wrong reason, since the roots of addiction to alcohol are far more complicated than any simplistic explanation such as self-loathing. The Code was also powerless to prevent Wilder and Brackett from finessing the suggestion that the friendly "bar girl" Gloria (Doris Dowling) is anything but an on-call prostitute. Increasingly, post-World War II films would treat audiences like the adults the Code administration wanted to prevent them from being. Wyman's Helen is a bit too noble in her persistent support of Birnam's behavior -- she moves from ignorance to denial to enabling to self-sacrifice far too swiftly and easily. But in general, the supporting cast -- Phillip Terry as Birnam's brother, Howard Da Silva as the bartender, Frank Faylen as the seen-it-all-too-often nurse in the drunk ward -- are excellent. The fine cinematography is by John F. Seitz. The score, which is laid on a bit too heavily, especially in the use of the theremin to suggest Birnam's aching need for a drink, is by Miklós Rózsa.

Saturday, June 4, 2016

Interstellar (Christopher Nolan, 2014)

All contemporary space travel sci-fi operates in the shadow of 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968), and the best you can do -- as Interstellar's Christopher Nolan and co-scenarist Jonathan Nolan do -- is to acknowledge it without imitating it. I think the fact that production designer Nathan Crowley's robots are slab-like (rather than the android designs we're familiar with) is one nod to Kubrick's film. But more to the point is that 2001 and Interstellar are both about human evolution. Kubrick makes the point more economically than Nolan does, without resorting to theories about wormholes and black holes allowing humans to travel beyond the confines of the fixed speed of light in order to discover an escape from the fate of Earth. In Nolan's film, that fate is dire, a world in which food shortages have led to mass starvation and a cultivation of anti-scientific attitudes. In Nolan's not-so-distant future, bright young people are being indoctrinated with what sounds a lot like current dogma in the more backward parts of the United States. (I'm trying not to say Texas here.) The children of former NASA pilot Joseph Cooper (Matthew McConaughey) are being told not only that farming is a nobler profession than engineering, but also that the United States faked the Apollo moon landings in order to deceive the Soviet Union into a buildup in space and military technology that would ruin the Soviet economy. Crazier theories have been advanced even in the current presidential election campaign. The trouble with the film is that eventually it has to come back to Earth and provide a rather muddled and disjointed resolution of the crisis it has presented and tried to solve. Meanwhile, the film is also tasked with trying to explicate for a non-scientific audience some cutting-edge theories in physics and cosmology. That necessitates an almost three-hour run time in which the audience is alternately dazzled by special effects and subjected to head-spinning theories. Some very attractive and skilled actors are enlisted in the effort: McConaughey, Anne Hathaway, Jessica Chastain, Michael Caine, Matt Damon, John Lithgow, and Ellen Burstyn among many others. But entertaining as it often is, Interstellar never quite makes it past the point of gee-whiz tinkering with some intriguing ideas into potential classic movie status.

Friday, June 3, 2016

Show Boat (James Whale, 1936)

Productions of Show Boat over the years are almost a barometer of the changes in racial attitudes. In the original 1927 Broadway production, for example, the opening song, "Cotton Blossom," sung by dock workers, contained the line "Niggers all work on the Mississippi." The 1936 film changed the offensive word to "Darkies," which today is only somewhat less offensive, so contemporary performances usually change the line to "Here we all work on the Mississippi." Today, we wince when Irene Dunne as Magnolia appears in blackface to sing "Gallivantin' Aroun'," a number created for the film, and we have to acknowledge that minstrelsy was still prevalent well into the mid-20th century. But Show Boat also presents structural problems. It is front-loaded with its best Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II songs: In the original production, "Make Believe," "Ol' Man River," "Can't Help Lovin' Dat Man," "Life Upon the Wicked Stage," and "You Are Love" all appear in Act I, leaving only "Why Do I Love You?" and "Bill" for Act II, among reprises of some of the other songs plus some oldies like "After the Ball." The film doesn't solve that problem: In fact, it omits "Life Upon the Wicked Stage" and "Why Do I Love You?" entirely, except as background music. It replaces them with a few new songs, including "I Have the Room Above You," a duet for Magnolia and Gaylord Ravenal (Allan Jones), and "Ah Still Suits Me," a somewhat too racially stereotyped duet for Joe (Paul Robeson) and Queenie (Hattie McDaniel), but they're still part of the first half of the film. And the plot seems to dwindle off into anticlimax after Gaylord leaves Magnolia. But James Whale's film version is one of the most successful translations of an admittedly imperfect stage musical to the screen. One reason is that it gives us a chance to see two legendary performers, Paul Robeson and Helen Morgan. Robeson's version of "Ol' Man River" is not only splendidly sung, but Whale also gives it a magnificent staging, beautifully filmed by John J. Mescall, that emphasizes the backbreaking toil that Robeson's Joe sings about. Morgan's performance as Julie makes me wish that Kern and Hammerstein had given her more songs, but her "Bill" is extraordinarily touching, and "Can't Help Lovin' Dat Man" becomes, after her introduction, a lively ensemble number for her, Dunne, McDaniel, and Robeson. It's also good to see McDaniel in a role that gives her a chance to sing -- she began her career as a singer. Too bad that Queenie's big number, "Queenie's Ballyhoo," was cut from the film. MGM remade Show Boat in 1951, with Kathryn Grayson as Magnolia, Howard Keel as Gaylord, and Ava Gardner as Julie, under the direction of George Sidney. Lena Horne wanted to play Julie, but the studio chickened out, fearing the reaction in the South. (Gardner's singing was dubbed by Annette Warren.) MGM also tried to suppress the 1936 film, which is vastly superior. Fortunately, it failed.

Thursday, June 2, 2016

The Rules of the Game (Jean Renoir, 1939)

The first time I saw The Rules of the Game, many years ago, I didn't get it. I knew it was often spoken of as one of the great films, but I couldn't see why. I had been raised on Hollywood movies, which fell neatly into their assigned slots: love story, adventure, screwball comedy, satire, social commentary, and so on. Jean Renoir's film seemed to be all of those things, and none of them satisfactorily. I had to be weaned from narrative formulas to realize why this sometimes madcap, sometimes brutal tragicomedy is regarded so highly. And I had to learn why the period it depicts, the brink of World War II, isn't just a point in the rapidly receding past, but the emblematic representation of a precipice that the human world always seems poised upon, whether the chief threat to civilization is Nazism or global climate change. The Rules of the Game is about us, dancing merrily on the brink, trying to ignore our mutual cruelty and to deny our blindness. Renoir's characters are blinded by lust and privilege, and they amuse us until they do horrible things like wantonly slaughter small animals or play foolish games whose rules they take too lightly. I'm afraid that makes one of the most entertaining (if disturbing) films ever made seem like no fun at all, but it should really be taken as a warning never to ignore the subtext of any work of art. Much of the film was improvised from a story Renoir provided, to the glory of such performers as Marcel Dalio as the marquis, Nora Gregor as his wife, Paulette Dubost as Lisette, Roland Toutain as André, Gaston Modot as Schumacher, Julien Carette as Marceau, and especially Renoir himself as Octave. Renoir's camera prowls relentlessly, restlessly through the giddy action and the sumptuousness of the sets by Max Douy and Eugène Lourié. It's not surprising that one of Renoir's assistants was the legendary photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson. And, given my own initial reaction to the film, it's also not surprising that The Rules of the Game was a critical and commercial flop, trimmed to a nubbin of its original length, banned by the Vichy government, and after its negative was destroyed by Allied bombs in 1942, potentially lost forever. Fortunately, prints survived, and by 1959 Renoir's admirers had reassembled it for a more appreciative posterity.

Wednesday, June 1, 2016

The Lower Depths (Akira Kurosawa, 1957)

|

| Bokuzen Hidari in The Lower Depths |

Tuesday, May 31, 2016

Floating Weeds (Yasujiro Ozu, 1959)

|

| Machiko Kyo and Ganjiro Nakamura in Floating Weeds |

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)