A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Sunday, July 10, 2016

Ida (Pawel Pawlikowski, 2013)

A successful film needs the correct balance of story and style, and when the story is as straightforward as Ida's, there's a great risk of overwhelming it with stylistic tricks. A novice called Anna (Agata Trzebuchowska) is about to take her vows to become a nun when she learns that she has an aunt, Wanda Gruz (Agata Kulesza), who wants to meet her. It is the 1960s, and Wanda is a judge in the courts of the communist government with a reputation for having for having presided brutally over the show trials of the 1950s that solidified communist power. She tells Anna, who was raised in an orphanage, that she was born to Jewish parents, one of whom was Wanda's sister, and that her birth name was Ida Lebenstein. Anna goes with Wanda in search of the graves of her parents and the son whom Wanda left with them when she joined the resistance during the war. Along the way, the tough, hard-drinking, sexually liberated Wanda, determined to provoke Anna out of her ascetic, devout ways, picks up a handsome young hitchhiker named Lis (Dawid Ogrodnik), a jazz saxophonist on his way to a gig. The story that director Pawel Pawlikowski and co-screenwriter Rebecca Lenkiewicz develop from this situation is told in an austerely beautiful manner. Two cinematographers are credited: Lukasz Zal took over as director of photography after Ryszard Lenczewski became ill during filming; both were deservedly nominated for cinematography Oscars. Pawlikowski chose to film in black-and-white to evoke the Polish films of the 1960s, the era of the young Roman Polanski, Jerzy Skolimowski, and Andrzej Wajda, although it's more accurate to refer to the cinematography as monochrome because the use of the many shades of gray and the emphasis on the textures of walls and skies and landscapes is extraordinary. The images are also strikingly framed: Characters rarely appear in the direct center of the screen, but are shifted toward the bottom or the corner of images. (Remarkably, the film also sometimes moves the subtitles from the bottom to the top of the frame to accommodate this placement.) Such manipulations could be seen as mannered, but I think it works to suggest that the lives of the characters themselves have been placed somewhere slightly off-center.

Saturday, July 9, 2016

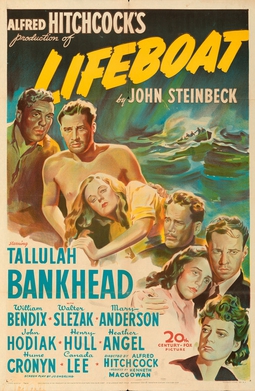

Lifeboat (Alfred Hitchcock, 1944)

Lifeboat has two things going for it: Alfred Hitchcock and Tallulah Bankhead. Otherwise, it could easily have turned into either a routine survival melodrama or, worse, a didactic allegory about the human condition. As it is, elements of both remain. The situation -- a small group of survivors of a merchant marine vessel torpedoed by a German U-boat confront the elements, their own frailties, and the U-boat captain they unwittingly help rescue -- was dreamed up by Hitchcock and was assigned to John Steinbeck to come up with a story. It was then turned into a screenplay by Jo Swerling, with the uncredited help of a number of other hands, including Ben Hecht and Hitchcock's wife, Alma Reville. Steinbeck is said to have hated it, partly because the screenplay was purged of his leftist point of view, but anyone familiar with his fiction can see how the script's avoidance of his tendency to preach strengthened the film. And the casting of Bankhead, in what is virtually her only good screen role, adds a note of sophisticated sass that the melodrama desperately needs. Steinbeck also objected that the character of Joe (Canada Lee), the ship's steward and the only black survivor, had been turned into a "stock comedy Negro," which is hardly fair: Although there are unpleasant taints of Hollywood racism in the characterization -- Bankhead's character refers to him as "Charcoal" a couple of times -- Joe is generally treated with respect. At one point, when the occupants of the lifeboat decide to put something to a vote, Joe asks, with more than a touch of sad experience behind the question, "Do I get to vote, too?" And when the survivors finally turn in a frenzy on the treacherous German (Walter Slezak), clubbing him to death and drowning him, Joe is the only one who seems to recognize that what they're doing is essentially a lynching; he tries to dissuade Alice (Mary Anderson), the U.S. Army nurse, from joining the assault. (Of course, it's also possible that the studio feared that having a black man assault a white man would outrage Southern audiences.) While it's not prime Hitchcock, Lifeboat is engaging and entertaining, and a cut above most wartime melodramas, partly because it dares to present the enemy, the German captain, as dangerous, cleverly outwitting and manipulating the Americans and Brits in the boat -- which naturally outraged some of the flag-waving critics.

Friday, July 8, 2016

Tokyo Story (Yasujiro Ozu, 1953)

Tokyo Story has everything we love about great short stories: a profoundly human situation, a delicate narrative restraint, and -- in the place of literature's powerfully evocative prose -- powerfully evocative images. It also has what literature can't give us: the joy of watching actors bring to life the characters they play. It is certainly one of my favorite films of all time, and while I've listed it at No. 1 on my Great Movies page, I think any horse-race competition to validate greatness does a film of such quiet power a disservice. How can you rank movies of such variety of tone as this subtle family drama, the violent picture of a disintegrating society in the first two Godfather films, the delicious intrigue of Notorious, and the epic portrait of medieval Russian life in Andrei Rublev, all of which currently constitute my so-called top five? I think Tokyo Story earns its place by establishing that there are universal constants in family life, things that transcend particular cultures: the gulf that widens between generations, the inability to face even those to whom one is closest without dissimulation, the tension between what one is obliged to say and do and what one actually feels at a moment of loss, and so on. Ozu and co-screenwriter Kogo Noda do a masterly job of gathering these and other themes and placing them in due order. This is one of those Ozu films where his technique of placing the camera almost at floor level seems like more than just a mannerism: It emphasizes that what we are seeing is rooted and basic, while at the same time we have the feeling of contact with the performers that we usually get only in the theater. Yuharu Atsuta's camera rarely moves, causing us to feel enveloped by Tatsuo Hamada's sets almost like participants in the lives of the Hirayama family, even though they are strangers to us, and their secrets and the flash points in their relationships -- such as the past drinking problem of the patriarch, Shukichi (the magnificent Chishu Ryu), or the deep loneliness of Noriko (Setsuko Hara), the widowed daughter-in-law -- gradually become known to us. This is a film that trusts its audience to stay and learn, something that has become lost in contemporary movies, which have to nudge audiences into awareness.

Thursday, July 7, 2016

Min and Bill (George W. Hill, 1930)

Remembered today chiefly because it was the film that won Marie Dressler the best actress Oscar (for what was by no means her best screen performance), Min and Bill is a good example of the struggle Hollywood movie-makers went through in adapting to sound. Dressler and co-star Wallace Beery had both been stars in silent films, and screenwriter Frances Marion was one of the most successful writers of that era. Unfortunately, Marion and co-screenwriter Marion Jackson don't seem to have mastered writing the dialogue a sound film needs for exposition and continuity, so it often sounds as if Dressler and Beery are ad-libbing just to keep the soundtrack alive. And director George W. Hill, a former cinematographer who had turned director before sound came in, doesn't quite know how to keep the pace from sagging. The result is a rather choppy movie with a few good scenes, most notably a knock-down, drag-out brawl between Dressler's Min and Beery's Bill. At the beginning of the film, Min seems to be destined to be one of Dressler's slapstick comic creations: There's an extended chase sequence in which Min and Nancy are at the controls of a runaway speedboat that culminates with Min being thrown overboard and hauled out of the water with repeated dunkings. But the main plot is sentimental drivel: Min runs a waterfront speakeasy/barbershop and has raised a girl, Nancy (Dorothy Jordan), left her as an infant by the now-aging prostitute Bella (Marjorie Rambeau). Now that Nancy is of marriageable age and is being wooed by the wealthy Dick Cameron (Don Dillaway), Bella has shown up again to try to claim the maternal privileges that she fears Min is going to assert. The trouble with this twist to the plot is that we never see Min being particularly loving and maternal toward Nancy, so that the denouement, in which Min tries to keep the girl out of Bella's clutches, doesn't make a lot of emotional sense. Still, the public loved it, and Dressler was for a time MGM's biggest star.

Wednesday, July 6, 2016

8 1/2 (Federico Fellini, 1963)

|

| Marcello Mastroianni in 8 1/2 |

Claudia: Claudia Cardinale

Louisa Anselmi: Anouk Aimée

Carla: Sandra Milo

Rossella: Rossella Falk

Gloria Morin: Barbara Steele

Madeleine: Madeleine Lebeau

La Saraghina: Eddra Gale

Pace, a Producer: Guido Alberti

Carini Daumier, a Film Critic: Jean Rouguel

Director: Federico Fellini

Screenplay: Federico Fellini, Ennio Flaiano, Tullio Pinelli, Brunello Rondi

Cinematography: Gianni Di Venanzo

Production design: Piero Gherardi

Music: Nino Rota

At one point in 8 1/2 an actress playing a film critic turns to the camera and brays (in English), "He has nothing to say!", referring to Guido Anselmi, the director Marcello Mastroianni plays and, by extension, to Fellini himself. And that's quite true: Fellini has nothing to say because reducing 8 1/2 to a message would miss the film's point. Guido finds himself creatively blocked because he's trying to say something, except he doesn't know what it is. He has even enlisted a film critic to aid him in clarifying his ideas, but the critic only muddles things by his constant monologue about Guido's failure. Add to this the fact that after a breakdown Guido has retreated to a spa to try to relax and focus, only to be pursued there by a gaggle of producers and crew members and actors, not to mention his mistress and his wife. Guido's consciousness becomes a welter of dreams and memories and fantasies, overlapping with the quotidian demands of making a movie and tending to a failed marriage. He is also pursued by a vision of purity that he embodies in the actress Claudia Cardinale, but when they finally meet he realizes how impossible it is to integrate this vision with the mess of his life. Only at the end, when he abandons the project and confronts the fact that he really does have nothing to say, can he realize that the mess is the message, that his art has to be a way of establishing a pattern out of his own life, embodied by those who have populated it dancing in a circle to Nino Rota's music in the ruins of the colossal set of his abandoned movie. The first time I saw this film it was dubbed into German, which I could understand only if it was spoken slowly and patiently, which it wasn't. Even so, I had no trouble following the story (such as it is) because Fellini is primarily a visual artist. Besides, the movie starred Mastroianni, who would have made a great silent film star, communicating as he did with face and body as much as with voice. It is, I think, one of the great performances of a great career. 8 1/2 is also one of the most beautiful black-and-white movies ever made, thanks to the superb cinematography of Gianni Di Venanzo and the brilliant production design and costumes of Piero Gherardi.

Tuesday, July 5, 2016

My Life As a Dog (Lasse Hallström, 1985)

The American success of Hallström's off-beat but lightweight film netted him two Oscar nominations: best director and -- with co-screenwriters Reidar Jönsson, Brasse Brännström, and Per Berglund -- best adapted screenplay. (The film was based on the middle volume of a trio of novels by Jönnson.) It also brought him to Hollywood, where he has directed more off-beat but lightweight films like What's Eating Gilbert Grape (1993), Chocolat (2000), and Salmon Fishing in the Yemen (2011). His most successful film after coming to the States has probably been The Cider House Rules (1999), for which he received another Oscar nomination for directing; it was the perfect teaming with a similarly off-beat and lightweight novelist, John Irving. Mind you, I have nothing against either the off-beat or the lightweight: My Life As a Dog is a perfectly charming and often touching movie that showcases a wonderful performance by young Anton Glanzelius as Ingemar, who gets tossed around from relative to relative as they try to cope with the boy. There are also excellent performances by Anki Lidén as Ingemar's mother, Tomas van Brömmsen as Uncle Gunnar, and Melinda Kinnaman (half-sister of the actor Joel Kinnaman) as the pubescent Sagar, who is distressed that her emerging femininity means an end to playing soccer and boxing with the boys. Jörgen Persson's cinematography is another plus. The trouble comes only when one tries to take My Life As a Dog too seriously as a coming-of-age tale, a genre much worked-over by the movies. The lightweightness of My Life as a Dog shows in comparisons with such classics of the genre as Satyajit Ray's Aparajito (1956), François Truffaut's The 400 Blows (1959), and even so recent an entry as Richard Linklater's Boyhood (2014), all of which more successfully integrate the coming-of-age tale with a specific time and place. By contrast, Ingemar's life seems to be taking place in a kind of whimsical neverland that just happens to look like rural Sweden. It's an often heartfelt and certainly entertaining movie that could have been much more.

Monday, July 4, 2016

L'Atalante (Jean Vigo, 1934)

L'Atalante is one of those near-universally acclaimed film masterpieces that failed theatrically on their first release and were rediscovered and re-evaluated more than a decade later. But it's also one of those films that young contemporary movie lovers may not "get" on first viewing today. I remember my own reaction to films like The Rules of the Game (Jean Renoir, 1939) and L'Avventura (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1960), movies that didn't fit what I expected from being raised on energetic, plot-driven, star-centered American movies. Melancholy and irony are not widely praised American values, although lord knows we have plenty of it in the best American literature. They surfaced for a time in the best American films of the 1970s, but have been driven back into the underground by the blockbuster mentality. There was a time, even after the great cinematic awakening of the '70s when I found myself resenting film critics for their inability to appreciate popular movies I enjoyed: "Critics see too many movies to enjoy them," I sniffed. But the truth is, the more movies you see, the more you're able to appreciate those that don't walk the line, that don't instantly gratify the hunger for plot resolution, for spectacle, for something that sends you out of the theater blissfully untroubled by thought. L'Atalante confused and bored its contemporary viewers, but today those of us who love it do so because it seems to us alternately tender and brutal, simultaneously comic and touching, and, taken as a whole, one of the few movies that successfully transport us to a time and place and a company of human beings we have never found ourselves in the middle of before. It is also, despite years of mishandling and cutting and botched attempts at restoration, one of the most technically dazzling films ever made. The performances -- by Michel Simon as the rather gross Père Jules, Dita Parlo and Jean Dasté as the young couple trying to start married life on a cramped river barge, and Gilles Margaritis as the madcap peddler who almost wrecks their marriage -- are extraordinary. Cinematographer Boris Kaufman overcame the severe limitations of filming scenes in the cramped quarters below-decks as well as open-air scenes for which the weather refused to cooperate. Vigo and Kaufman stage visual compositions that have a freshness that never seems arty. And who can ever forget Simon's Père Jules clambering aboard the barge with a kitten on his shoulders? Every corner of L'Atalante is filled with life.

Sunday, July 3, 2016

Good Morning (Yasujiro Ozu, 1959)

|

| Masahiko Shimazu and Koji Shitara in Good Morning |

Saturday, July 2, 2016

I Was Born, But.... (Yasujiro Ozu, 1932)

|

| Hideo Sugawara, Seiichi Kato, and Tomio Aoki in I Was Born, But.... |

Friday, July 1, 2016

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (Howard Hawks, 1953)

Given the sexism and vulgarity that underlies the teaming of Marilyn Monroe and Jane Russell -- two women best known at the time for their bodies, not for their talents as actresses or singers -- it's gratifying that Gentlemen Prefer Blondes turned out to be a landmark film in both their careers. Some of it has to do with the director, Howard Hawks, who despite his reputation for womanizing created some of the most memorable roles for such actresses as Katharine Hepburn, Jean Arthur, Rosalind Russell, Lauren Bacall, and many others. Certainly neither Russell nor Monroe ever showed more wit and liveliness than they do here, even though Monroe is playing the gold-digging ditz part that she came to resent, especially after having to play it again the same year in How to Marry a Millionaire (Jean Negulesco), and Russell is stuck with the wise-cracking sidekick role. Both stars are paired with lackluster leading men, Elliott Reid and Tommy Noonan, but while it might have been fun to see someone like Cary Grant in Reid's part, that kind of casting would probably have thrown the film off-balance. Better that we have Charles Coburn's bedazzled old lech, young George Winslow's precocious appreciation of Monroe's "animal magnetism," and Marcel Dalio's judge overwhelmed by Russell's hilarious impersonation of Monroe's Lorelei Lee. The production numbers, choreographed by Jack Cole, costumed by Travilla, and filmed by Harry J. Wild in a candy-store Technicolor that we'll not see the like of again, are exceptional showcases for Russell and Monroe: The former's baritonish growl blends perfectly with the latter's sweet and wispy soprano (though some of Monroe's high notes were provided by Marni Nixon).

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)

_film_poster.jpg)