A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Wednesday, November 23, 2016

What's Up, Doc? (Peter Bogdanovich, 1972)

As a film genre, the screwball comedy flourished for about a decade, from 1934 to 1944, or from Twentieth Century (Howard Hawks, 1934) to Hail the Conquering Hero (Preston Sturges, 1944.) Like so much else in movie history, including the Western, it was killed off by television, by half-hour sitcoms like I Love Lucy that slurped up its essence and made the 90-minute theatrical versions seem like overkill. We can still glimpse some of the heart of the screwball comedy in films like David O. Russell's Silver Linings Playbook (2012) and American Hustle (2013) or Wes Anderson's The Royal Tenenbaums (2001), but Peter Bodganovich's What's Up, Doc? is probably the last pure example of the genre as it was in its heyday. Like the masters of the genre -- Hawks and Sturges are the masters, but Gregory La Cava, George Stevens, Mitchell Leisen, and Frank Capra made worthy contributions -- Bogdanovich followed a few rules: One, get stars who usually played it straight to make fools of themselves. Two, make use of as many comic character actors as you can stuff into the film. Three, never pretend that the world the film is taking place in is the "real world." Four, never, ever let the pace slacken -- if your characters have to kiss or confess, make it snappy. On the first point, Bogdanovich found the closest equivalents to Cary Grant and Katharine Hepburn (or Clark Gable, Joel McCrea, James Stewart on the one hand, Rosalind Russell, Claudette Colbert, Jean Arthur on the other) that he could among the stars of his day. Ryan O'Neal was coming off the huge success of the weepy Love Story (Arthur Hiller, 1970) and a five-year run on TV's Peyton Place and Barbra Streisand had won an Oscar for Funny Girl (William Wyler, 1968). Granted, O'Neal is no Cary Grant: His timing is a little off and he overdoes a single exasperated look, but he makes a suitable patsy. But has Streisand ever been more likable in the movies? She plays the dizzy troublemaker with relish, capturing the essence of Bugs Bunny -- the other inspiration for the movie -- to the point that you almost expect her to turn to the camera and say, "Ain't I a stinker?" As to the second point, we no longer have character actors of the caliber of Eugene Pallette, Franklin Pangborn, or William Demarest, but Bogdanovich recruited some of the best of his day: Kenneth Mars, Austin Pendleton, Michael Murphy, and others, and introduced moviegoers to the sublime Madeline Kahn. And he set it all in the ever-picturesque San Francisco, while making sure no one would ever confuse the movie version with the real thing, including a chase sequence up and down its hills that follows no possible real-world path. And he kept the pace up with gags involving bit players: the pizza maker so distracted by Streisand that he spins his dough up to the ceiling, the banner-hanger and the guys moving a sheet of glass, the waiter who enters a room with a tray of drinks but takes one look at the chaos there and turns right around, the guy laying a cement sidewalk that's run over so many times by the car chase that he flings down his trowel and jumps up and down on his mutilated handiwork. This is masterly comic direction of a sort we don't often see -- and, sadly, never saw again from Bogdanovich, whose career collapsed disastrously with a string of flops in the mid-1970s. Here, he was working with a terrific team of writers, Buck Henry, David Newman, and Robert Benton, who turned his story into comedy gold.

Tuesday, November 22, 2016

The Passion of Joan of Arc (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1928)

|

| Renée Jeanne Falconetti in The Passion of Joan of Arc |

*So far, Filmstruck hasn't moved much beyond streaming on the computer, though it's supposed to be included on Roku early next year. In my household, with two others competing for bandwidth, this meant that I had frequent interruptions as the film refreshed itself. Oddly enough, I didn't mind as much as I usually would, because Dreyer's images are so compelling that I was content to pause and study them.

Monday, November 21, 2016

Wizard of Oz (Larry Semon, 1925)

|

| Dorothy Dwan and Larry Semon in Wizard of Oz |

Sunday, November 20, 2016

Queen Margot (Patrice Chéreau, 1994)

|

| Daniel Auteuil and Isabelle Adjani in Queen Margot |

Saturday, November 19, 2016

Jamaica Inn (Alfred Hitchcock, 1939)

According to Stephen Whitty's excellent The Alfred Hitchcock Encyclopedia, the director thought Jamaica Inn "completely absurd" and didn't even bother to make his familiar cameo appearance in it. Hitchcock was right: It's a ridiculously plotted and often amateurishly staged film -- although Hitchcock must take some of the blame for the scenes in which characters sneak around talking in stage whispers and pretending they're hidden from their pursuers when they're in plain sight for anyone with average peripheral vision. Much of Hitchcock's attitude toward the film has been ascribed to his clashes with Charles Laughton, who was an uncredited co-producer and resisted any attempts by the director to rein in one of his more ridiculous performances. As Sir Humphrey Pengallan, the county squire and justice of the peace who is secretly raking in a fortune by collaborating with smugglers who loot shipwrecked vessels after murdering their crew, Laughton wears a fake nose and oddly placed eyebrows and hams it up mercilessly. Maureen O'Hara, in her first major film role, struggles with a confusingly written character who sometimes displays fire and initiative and at other times seems alarmingly obtuse. The rest of the cast includes such stalwarts of the British film and stage as Leslie Banks, Emlyn Williams, and Basil Radford, with a surprising performance by Robert Newton as the movie's romantic lead, Jem Traherne, an agent working undercover to expose the smugglers. You look in vain at the young Newton for traces of his terrifying Bill Sykes in Oliver Twist (David Lean, 1948) or his Long John Silver in Treasure Island (Byron Haskin, 1950). The production design is handsome, and the film begins with an exciting storm at sea, but the screenplay, based on a Daphne Du Maurier novel and written by the usually capable Sidney Gilliat and Joan Harrison, quickly falls apart. Hitchcock's last film in England, Jamaica Inn was a critical flop but a commercial success.

Friday, November 18, 2016

The Mirror (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1975)

What are the limits of narrative cinema? If, indeed, The Mirror is narrative -- that question needs to be developed in more ways than I care to go into here. It's easy to say that Andrei Tarkovsky's film is non-linear, jumping back and forth in time with no clues about when and where we are in any given moment. Even the switches from black-and-white to color turn out to be red herrings if you're trying to sort out chronology. There is a fine line between frustration and stimulation, and Tarkovsky dances along it as we the viewers similarly traverse the line between ennui and involvement. It is, I gather from reading several essays that reinforce my impressions of the film, a memory piece in which Alexei, a man on his deathbed, recalls his childhood in Russia before, during, and after World War II. His memories include his mother, Maria, and his wife, Natalia, both played beautifully by Margarita Terekhova. Similarly, Ignat Daniltsev plays both the young Alexei and his son, Ignat. There are lucid episodes throughout the film, mixed with newsreel footage from the wartime and postwar periods, along with bits of fantasy and surrealism. I would like to say that The Mirror is hypnotic, because it begins with a scene in which a therapist uses hypnotism to try to cure a young man of a speech impediment, but that oversimplifies the effect of the film. I love and admire the previous Tarkovsky films I have seen -- Ivan's Childhood (1962), Andrei Rublev (1966), and Solaris (1972) -- but I will have to see it again to decide if I want to join the consensus on its greatness: It took 19th place in the 2012 Sight and Sound critics poll of the greatest films of all time, and an astonishing 9th place in the directors' poll. I concede that it is "poetic," including the fact that Arseniy Tarkovsky, the director's father, reads his own poems in the film, and there are scenes of extraordinary beauty, the work of cinematographer Georgi Rerberg. But is that all we should ask of a film?

Thursday, November 17, 2016

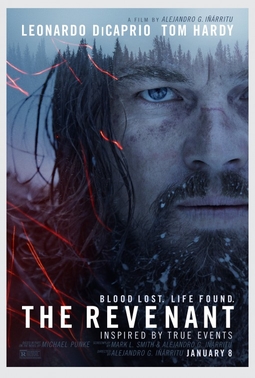

The Revenant (Alejandro González Iñárritu, 2015)

I have suggested before, in my comments on Birdman (2014), Babel (2006), and 21 Grams (2003), that in Alejandro G. Iñárritu's films there seems to be less than meets the eye, but what meets the eye, especially when Emmanuel Lubezki is the cinematographer, as he is in The Revenant, is spectacular. The Revenant had a notoriously difficult shoot, owing to the fact that it takes place almost entirely outdoors during harsh weather, and it went wildly over-budget. Leonardo DiCaprio underwent significant hardships in his performance as Hugh Glass, the historical fur trader who became a legend for his story of surviving alone in the wilderness after being mauled by a grizzly bear. In the end, it was a major hit, more than making back its costs and getting strong critical support and 12 Oscar nominations, of which it won three -- for DiCaprio, Lubezki, and Iñárritu. I won't deny that it's an impressive accomplishment, and probably the best of the four Iñárritu films I've seen. It's full of tension and surprises, and fine performances by DiCaprio; Tom Hardy as John Fitzgerald, the man who leaves Glass to die in the wilderness; and the ubiquitous Domhnall Gleeson as Andrew Henry, the captain of the fur-trapping expedition who aids Glass in his final pursuit of Fitzgerald. Lubezki's cinematography, filled with awe-inspiring scenery and making good use of Iñárritu's characteristic long tracking takes, fully deserves his third Academy Award, making him one of the most honored people in his field. The visual effects blend seamlessly into the action, especially in the harrowing grizzly attack. And yet I have something of a feeling of overkill about the film, which seems to me an expensive and overlavish treatment of a tale of survival and revenge -- great and familiar themes that have here been overlaid with the best that today's money can buy. The film concentrates on Glass's suffering at the expense of giving us insight into his character. It substitutes platitudes -- "Revenge is in God's hands" -- for wisdom. And what wisdom it ventures upon, like Glass's native American wife's saying, "The wind cannot defeat the tree with strong roots," is undercut by the absence of characterization: What, exactly, are Glass's roots?

Wednesday, November 16, 2016

O Brother, Where Art Thou? (Joel Coen and Ethan Coen, 2000)

On the scale for goofy Coen brothers films, O Brother, Where Art Thou? falls somewhere between Raising Arizona (1987) and The Big Lebowski (1998) from goofiest to least goofy. It is, I think, more over-the-top than is absolutely necessary, especially in the idiot hick accents adopted by John Turturro and Tim Blake Nelson in their roles. Or maybe they just seem that way because of the differently over-the-top performance of George Clooney as Ulysses Everett McGill, a man who thinks he talks more intelligently than he does. Still, I like Clooney in this mode, more than I do when he's playing a serious character, and it's to the Coens' credit that they cast him in the role: His performance gives an odd kind of off-balance stability to that of the other two. The chief glory of the movie, however, is its music, chosen by T Bone Burnett, superbly evoking a time and place. As for that time and place, Depression-era Mississippi, the movie pretty much ignores reality in favor of goofing around. It was the era of Bilbo and Vardaman, politicians of deeply cynical evil, and the rival candidates played by Charles Durning and Wayne Duvall don't even approach their horror, even when lampooning it. I laughed when the Ku Klux Klan performed what looked like a marching band half-time routine with a chant that evokes the parading monkey guards in The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming, 1939), but maybe it's the outcome of the recent presidential election that made me feel a little nauseated at even the notion of a comical Klan. A kind of irresponsibility mars the Coens' approach to the material, brilliantly funny as it often is. That said, the pacing of the movie is lively, and it's filled with ever-watchable performers like Durning, Holly Hunter, and John Goodman at their best. And there's always that music: If I'm inclined to forgive the Coens for their irresponsibility, it's because they introduced a lot of people who went out and bought the soundtrack album to some great music.

Tuesday, November 15, 2016

Children of Men (Alfonso Cuarón, 2006)

|

| Clive Owen in Children of Men |

Julian: Julianne Moore

Jasper: Michael Caine

Kee: Claire-Hope Ashitey

Luke: Chiwetel Ejiofor

Patric: Charlie Hunnam

Miriam: Pam Ferris

Syd: Peter Mullan

Nigel: Danny Huston

Marichka: Oana Pellea

Ian: Phaldut Sharma

Tomasz: Jacek Koman

Director: Alfonso Cuarón

Screenplay: Alfonso Cuarón, Timothy J. Sexton, David Arata, Mark Fergus, Hawk Ostby

Based on a novel by P.D. James

Cinematography: Emmanuel Lubezki

Production design: Jim Clay, Geoffrey Kirkland

Film editing: Alfonso Cuarón, Alex Rodríguez

Music: John Taverner

George Lucas did something shrewd when he prefaced his first Star Wars movie in 1977 with the phrase "A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away." Deliberately echoing the formulaic "Once upon a time," Lucas emphasized the fairy-tale essence of his science-fiction fable. But other creators of science fiction haven't been so careful, or perhaps have been more insouciant. George Orwell's 1984 was written in 1948, and all Orwell did was set the novel in a year that inverted the last two digits of the year of its completion. He wasn't presenting a literal forecast of actual life in the year 1984, he was serving as a prophet of what was actually present and nascent in his own time: totalitarianism and pervasive invasion of privacy. So 32 years later, we still find an uneasy resonance of Orwell's book in our own times. Similarly, when Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clark teamed to write the screenplay for 2001: A Space Odyssey (Kubrick, 1968), they weren't necessarily predicting deep exploration of the solar system and encounters with mysterious monoliths -- though I rather suspect they were hoping for at least the first -- but rather speculating on the origins of human nature and consciousness and their relationship to artificial intelligence. Similarly, the dystopian world of Blade Runner (Ridley Scott, 1982), populated by replicants and traversed by flying cars, is supposedly set in 2019 -- a year now close at hand -- but is also centrally concerned with the nature of humanity in a corporate capitalist society. What I'm getting at is that sometimes science fiction writers and filmmakers distance themselves as Lucas does from any notion that they're commenting on the "real world," but sometimes embrace a specific foreseeable date, with a view to making either a prediction of the way things will evolve or a comment on the problems of their own day. This is why I find Alfonso Cuarón's Children of Men such a puzzling film. It gives us a dank dystopian London that resembles the dank dystopian Los Angeles of Blade Runner, and it sets it in a specific time, the year 2027, a world in which human beings stopped bearing children 18 years earlier: i.e., in the year 2009 -- only three years after the film was made. But unlike Blade Runner, it doesn't seem to be telling us anything specific about either a predicted future or the way we lived then. It's a very entertaining film, full of violent action and suspense, with some wizardly work by Oscar nominees cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki and editors Cuarón and Alex Rodríguez. The way they handle the film's much-praised long-take sequences, aided by special effects to give the sense of complex action taking place in a single traveling shot, is exceptional -- anticipating Lubezki's work in making the entirety of Birdman (Alejandro González Iñárritu, 2014) seem to be a continuous take. There are also fine performances by Clive Owen, Julianne Moore, Chiwetel Ejiofor, Clare-Hope Ashitey, and the inevitably wonderful Michael Caine. But what is at the core of the film? Why does the failure of humankind to reproduce precipitate the worldwide cataclysm that the movie presents us? We have fretted so long about overpopulation that it would seem a blessing to have at least a pause in it, in which the world's scientists might take time to resolve the problem, or at least to discover the reason for the widespread infertility. Instead, we have a story that's largely about the mistreatment of immigrants. Why would non-reproducing immigrants, in a world with a declining population and therefore less pressure on natural resources, be a problem? Is it possible that this film, based on but radically altered from a novel by P.D. James, is promoting the extreme "pro-life" view, not only anti-abortion but also anti-contraception? Or is it simply that, as one character puts it, "a world without children's voices" is inevitably a terrible place? The film's failure to suggest a larger context for its action seems to me to by a weakness in an otherwise extraordinary film.

Monday, November 14, 2016

Pigsty (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1969)

Pier Paolo Pasolini's Pigsty is too much like what people think of when they hear the phrase "art house movie," especially when they have in mind films of the late 1960s. It's enigmatic and disjointed, and has a tendency to treat images as if they were ideas -- significant ideas. There are two narratives at work in the film: One features Pierre Clémenti as some kind of feral human wandering a volcanic landscape in which he finds a butterfly and a snake and eats both, then dons the helmet and musket he finds beside a skeleton. It's some unspecified pre-modern era -- the helmet and the garb of the soldiers and priests he meets later make think 17th century. He kills and eats another man he meets, then begins to gather a group of fellow cannibals. The other story takes place in Germany in 1967 and centers on Julian Klotz (Jean-Pierre Léaud), the son of a wealthy ex-Nazi (Alberto Lionello) who styles his hair and mustache like his late Führer and is pursuing a merger with a Herr Herdhitze (Ugo Tognazzi), who is a rejuvenated Heinrich Himmler, having undergone extensive plastic surgery. Julian, meanwhile, is an aimless youth who resists the urgings of his fiancée, Ida (Anne Wiazemsky) to join in leftist protest movements and to have sex with her. He'd rather spend time with the pigs in a nearby sty. The efforts at satire in the modern section are as heavy-handed as they sound in this summary, especially since Pasolini has chosen to have much of the exposition delivered by the actors in the flat-footed style of a 19th-century melodrama. There are some acting standouts, however, in both sections, especially Léaud, who seems to be having more fun than his role allows; Clémenti and Pasolini regular Franco Citti throw themselves into their feral roles, and Tognazzi is suavely menacing in his. If the whole thing is meant as a satire on dog-eat-dog (or man-eat-man or pig-eat-man) capitalism, it is sometimes too oblique and sometimes too blatant. Pasolini is a challenging, original filmmaker as always, but this one doesn't transcend the often inchoate artistic fervor of the '60s avant garde.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.png)

.jpg)