|

| Radoslav Brzobohaty and Jirina Bohdolová in The Ear |

A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Saturday, January 14, 2017

The Ear (Karel Kachyna, 1970)

Friday, January 13, 2017

World on a Wire (Rainer Werner Fassbinder, 1973)

What we call "reality" is, as we all know now, a construct, the product of the limitations of our senses. But what if we, too, are part of the construct, put here by some other entity and blinded to the reality that lies beyond the senses? That way lies religion -- "Now we see through a glass darkly...." -- and metaphysics -- now largely dismissed as "asking unanswerable questions" -- but also science fiction. Witness the popularity of a film like The Matrix (Lana Wachowski and Lilly Wachowski, 1999) and its sequels. In fact, Rainer Werner Fassbinder got there more than two decades before the Wachowskis. In 1973 he created a two-part television series, World on a Wire, that aired in Germany, and then became a kind of cult hit via file-sharing on the internet before being restored in 2010 and screened at the Berlin Film Festival. In it, a German research institute has created a simulated world in its supercomputer. The inhabitants of this world have been given consciousness, but only one of them has knowledge of the world outside the computer. He serves as a contact between the programmers and the simulated beings. But then the sudden death of the head of the program puts his second-in-command, Stiller (Klaus Löwitsch), in charge of investigating not only the death of his predecessor but also the suicide of one of the simulated beings. Stranger and stranger things begin to happen, until Stiller learns that he is also a simulation in his own simulated world. He also learns that the institute's simulated world is being used for commercial purposes, something that violates its agreement with the government funding it. As he comes to terms with this knowledge, his increasingly erratic behavior makes him a target for assassins, and his one hope is to find the contact with the level above that's simulating him. Got that? The head-spinning premise of the film comes from a novel, Simulacron-3, by the American writer Daniel F. Galouye, adapted by Fassbinder and Fritz Müller-Scherz. Fassbinder gives it a good deal of his characteristic style in the adaptation: The women in Stiller's world, for example, always wear cocktail dresses, even at work, and rooms are filled with mirrors to suggest the layers of reflected reality in the three levels. The costume designer is Gabriele Pillon and the production design is by Horst Giese, Walter Koch, and Kurt Raab. It was filmed in 16 mm for television, which means there's some graininess and focus problems in some parts of the restored film, but the cinematography is by Fassbinder's frequent collaborator Michael Ballhaus, along with Ulrich Prinz. Löwitsch is very good as Stiller, taking on kind of James Bondian role, and the paranoid atmosphere prevails even when the plot gets a bit snarled in its own premise.

Thursday, January 12, 2017

Two With Marcello Mastroianni

A Slightly Pregnant Man (Jacques Demy, 1973)

Irène de Fontenoy: Catherine Deneuve

Marco Mazetti: Marcello Mastroianni

Dr. Delavigne: Micheline Presle

Maria Mazetti: Marisa Pavan

Director: Jacques Demy

Screenplay: Jacques Demy

Cinematography: Andréas Winding

Production design: Bernard Evein

Music: Michel Legrand

A Special Day (Ettore Scola, 1977)

Antonietta: Sophia Loren

Gabriele: Marcello Mastroianni

Emanuele: John Vernon

Caretaker: Françoise Berd

Director: Ettore Scola

Screenplay: Ruggero Maccari, Ettore Scola, Maurizio Costanzo

Cinematography: Pasqualino De Santis

Production design: Luciano Ricceri

The great charm of Marcello Mastroianni lies, I think, in the fact that he always seems to be the odd man out. Despite his good looks and sex appeal, there is always the sense that the characters he plays, even though they attract women on the order of Catherine Deneuve and Sophia Loren, are never quite in charge of the world they inhabit. Certainly this is true of his most famous roles, Marcello in La Dolce Vita (Federico Fellini, 1960) and Guido in 8 1/2 (Fellini, 1963). And directors Jacques Demy and Ettore Scola exploit this otherness in Mastroianni in very different ways: Demy in the satiric A Slightly Pregnant Man and Scola in the earnest A Special Day. In the former film, whose French title was the lengthy L'Événement le plus important depuis que l'homme a marché sur la Lune (The Most Important Event Since Man Walked on the Moon), Mastroianni plays Marco, a driving-school instructor who feels out of sorts and goes to see a doctor who decides that he must be pregnant. When a well-known specialist confirms the diagnosis and presents his findings to other scientists, the press goes wild and the advertising department for a maternity-wear company launches a campaign for male maternity clothes. Marco winds up on posters everywhere, and he and his fiancée, Irène, begin to make big plans for the money the company pays him. Eventually, the diagnosis proves to be false, however, and the film concludes with an anticlimactic thud. Demy, whose best-known work is probably the cotton-candy musicals The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964) and The Young Girls of Rochefort (1967), seems to have launched into his screenplay with no sense of how to end it satisfactorily. Until that point, however, Mastroianni and Deneuve have fun with their roles. Forgoing her usual sophisticated chic, she plays a somewhat blowsy beauty-shop owner. A Special Day earned Mastroianni one of his three Oscar nominations, partly because there's nothing the Academy likes better than a straight actor daring to play gay. He is Gabriele, a radio announcer who has lost his job because the Fascists have begun purging the work force of "undesirables." The day is May 8, 1938, when Hitler visits Mussolini in Rome to solidify their alliance. He lives in a large apartment complex with windows facing an open courtyard. Across the way lives Antonietta, a woman with an abusive husband and six children. On this day, she has stayed home to clean house after sending her family off to the parades and speeches, but when the family's pet mynah bird escapes and flies out into the courtyard, she asks Gabriele's help in retrieving him. They are virtually the only people left in the complex other than the nosy, gossipy concierge, whose radio is blaring the news of the day -- Fascist anthems, speeches, the cheers of the crowd, and a running patriotic commentary -- which serves as the sometimes ironic counterpoint to the growing intimacy of the mismatched couple. A severely deglamourized Loren gives a fine performance, as does Mastroianni: Gabriele is aware that at any moment he may be taken away to a concentration camp, and he vacillates between suicide and a carpe diem fatalism. The film is a little too predictable, and although the screenplay by Scola and Ruggero Maccari is original, it feels somewhat like an adaptation of a two-character stage play. Pasqualino De Santis's cinematography, using long takes and tracking shots through the apartment complex (which we never leave except in the archival newsreel footage at the film's beginning), helps open it up.

|

| Catherine Deneuve and Marcello Mastroianni in A Slightly Pregnant Man |

Marco Mazetti: Marcello Mastroianni

Dr. Delavigne: Micheline Presle

Maria Mazetti: Marisa Pavan

Director: Jacques Demy

Screenplay: Jacques Demy

Cinematography: Andréas Winding

Production design: Bernard Evein

Music: Michel Legrand

A Special Day (Ettore Scola, 1977)

|

| Marcello Mastroianni and Sophia Loren in A Special Day |

Gabriele: Marcello Mastroianni

Emanuele: John Vernon

Caretaker: Françoise Berd

Director: Ettore Scola

Screenplay: Ruggero Maccari, Ettore Scola, Maurizio Costanzo

Cinematography: Pasqualino De Santis

Production design: Luciano Ricceri

Wednesday, January 11, 2017

The Great McGinty (Preston Sturges,1940)

|

| Poster with the British title for The Great McGinty |

Tuesday, January 10, 2017

Two by Jean Renoir

Boudu Saved From Drowning (Jean Renoir, 1932)

|

| Michel Simon in Boudu Saved From Drowning |

Édouard Lestingois: Charles Granval

Emma Lestingois: Marcelle Hainia

Chloë Anne Marie: Sévérine Lerczinska

Vigour: Jean Gehret

Godin: Max Dalban

A Student: Jean Dasté

Director: Jean Renoir

Screenplay: Jean Renoir, Albert Valentin

Based on a play by René Fauchois

Cinematography: Georges Asselin

A Day in the Country (Jean Renoir, 1936)

|

| Sylvia Bataille and Georges D'Arnoux in A Day in the Country |

Henri: Georges D'Arnoux

Madame Dufour: Jane Marken

Monsieur Dufour: André Gabriello

Rodolphe: Jacques B. Brunius

Anatole: Paul Temps

Grandmother: Gabrielle Fontan

Uncle Poulain: Jean Renoir

Waitress: Marguerite Renoir

Director: Jean Renoir

Screenplay: Jean Renoir

Based on a story by Guy de Maupassant

Cinematography: Claude Renoir

Music: Joseph Kosma

"Épater la bourgeoisie!" went the rallying cry of France's 19th-century poets like Baudelaire and Rimbaud, who styled themselves as "Decadents." But ever since Molière's M. Jourdain, the social-climbing bourgeois gentilhomme, was delighted to discover that he was speaking prose, French artists of whatever medium have delighted themselves in satirizing the manners and morals of the middle class, sometimes affectionately and sometimes savagely. On my living room wall I have two prints of cartoons done by Honoré Daumier in a series he called "Pastorales." Both show very solidly middle-class and middle-aged couples, presumably Parisians taking a day in the country. In one, the husband carries his large, copiously clad wife on his back as he fords a small stream that barely comes to his ankles. They have evidently been caught in a summer storm, for he is chiding her that such things are to be expected, even on the sunniest day. Meanwhile, she is urging him, "Ah, Jules, don't let the torrent sweep us away!" In the other, a similarly clad woman sits on the bank of a pond in which her husband, wearing his glasses and with his head wrapped in a handkerchief, has been taking a dip. "The water is delicious, Virginie," he says. "I assure you, you're making a mistake by not joining me." I was reminded of these prints while watching Jean Renoir's great short film -- it's only 40 minutes long, but every minute is golden -- A Day in the Country. In it, the Dufour family -- husband, wife, daughter, future son-in-law, and comically deaf grandmother -- find a country inn in a beautiful setting on their day away from the city. The mother and daughter immediately become targets for two young men, who manage to set off with them in their skiffs on the river, after diverting the other men by lending them fishing poles. The daughter, Henriette, goes with Henri. When a storm comes up, they take shelter in the woods, where she yields to his advances. Years later, she returns to the same spot with her husband, Anatole, an unromantic drip, and while he naps, she encounters Henri and recalls their brief encounter. The film is an exquisite mix of comedy and melancholy, the kind of subtle blending of tones Renoir is known for from his greatest films, The Grand Illusion (1937) and The Rules of the Game (1939). A Day in the Country was in fact never finished -- weather interrupted the shooting and Renoir had to move on to another commitment -- but the existing footage was assembled ten years later under the supervision of the producer, Pierre Braunberger, with two explanatory intertitles, and it stands on its own as a masterwork. In sharp contrast to the affectionately amused treatment of the bourgeoisie in A Day in the Country, Boudu Saved From Drowning is a raucous free-for-all centered on the great eccentric Michel Simon in the title role. Boudu is a tramp, a shaggy monster, who after his dog runs away decides to drown himself in the Seine. But he is rescued by Édouard Lestingois, a bookseller, who takes him into his home. Boudu proceeds to trash the place and seduce both Mme. Lestingois and the housemaid, who is also Lestingois' mistress. Simon's performance pulls out all the stops in one of the greatest comic tours de force in film history. If you want to see what épater la bourgeoisie really means, just watch Boudu.

Monday, January 9, 2017

The Man Who Knew Too Much (Alfred Hitchcock, 1934)

|

| Peter Lorre, Leslie Banks, and Nova Pilbeam in The Man Who Knew Too Much |

Sunday, January 8, 2017

Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (Pedro Almodóvar, 1988)

Pedro Almodóvar's brightly colored farce Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown put him on the map as an auteur to be reckoned with. It's a grand stew of a film that takes the premise of Jean Cocteau's serious play La Voix Humaine and turns it into a nod to classic Hollywood screwball comedy touched with feminism and the brand of liberated hedonism peculiar to post-Franco Spain. It's also a superb product of the gay sensibility, to the point that it's easy to imagine the roles of Pepa (Carmen Maura), Candela (Maria Barranco), Marisa (Rossy de Palma), and Lucia (Julieta Serrano) played by drag queens. But although it verges on camp -- Pepa, a soap opera actress, dubs Joan Crawford's voice in a Spanish release of Nicholas Ray's perhaps unintentionally camp Western Johnny Guitar (1954) -- it has at its core Almodóvar's genuine affection for his characters. The gloriously sunny decor of the film is the product of set decorators José Salcedo and Félix Murcia, and the costumes are by José María de Cossío. The cinematographer is Almodóvar's frequent collaborator José Luis Alcaine.

Saturday, January 7, 2017

The Sound and the Fury (James Franco, 2014)

James Franco gets mocked for overreaching -- writing fiction, directing avant-garde films and multimedia art, taking graduate level courses at a variety of universities simultaneously -- and for what many see as an eccentric persona. So I don't want to come off as a mocker in my criticism of his film version of William Faulkner's The Sound and the Fury. It's a failure for a variety of reasons, not least the extreme difficulty of translating into visual terms a novel that succeeds in the way its author uses language to convey the inner states of his characters. Franco makes the serious mistake of casting himself as the most interior and inarticulate of Faulkner's characters, the mentally handicapped Benjy Compson. Distractingly outfitted with oversize front teeth, Franco struggles to portray Benjy's torment at the loss of his beloved sister Caddy (Ahna O'Reilly), amid the declining fortunes of the Compson family. He can't dim the intelligence in his own eyes enough to suggest the blind struggle of memory and desire and frustration within the character. The screenplay by Matt Rager, who has also adapted Faulkner's As I Lay Dying (2013) and John Steinbeck's In Dubious Battle (2016) for Franco to direct, does a fairly good job of sticking to the narrative line of the novel: Benjy's loss, the suicide of his older brother Quentin (Jacob Loeb), the marriage that Caddy enters into because she is impregnated by Dalton Ames (Logan Marshall-Green), Caddy's sending her daughter, also named Quentin (Joey King), to live with the Compsons, and the rage of the youngest brother, Jason (Scott Haze), when the teenage Quentin runs away from home with the money he has hoarded after stealing it from the funds Caddy has sent for Quentin's support. Rager also draws heavily on the sententious speeches of the Compson children's ineffectual alcoholic father (Tim Blake Nelson), taken directly from the novel. The screenplay skimps on the key role played in the novel by the black servants, particularly that of Dilsey (Loretta Devine). Most of the performances are quite good, with the exception of Janet Jones Gretzky as the mother; she looks far too healthy, and never strikes the note of decayed gentility that the role demands. There are also some unnecessarily distracting cameos by Seth Rogen as a telegraph clerk and Danny McBride as the sheriff, bit parts that didn't need to be cast so prominently. As a whole, the film feels like the work of an amateur filmmaker with exceptional film industry connections, and that, I guess, is the very definition of overreaching.

Friday, January 6, 2017

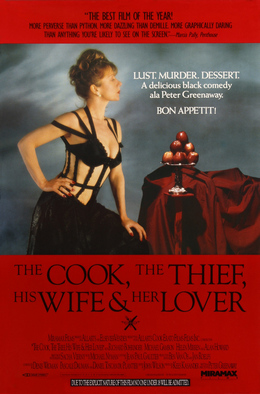

The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover (Peter Greenaway, 1989)

I have to imagine some naive young person whose idea of outrageous filmmaking extends no further than the work of David Lynch or Quentin Tarantino, and who knows Helen Mirren only as the Oscar winner for The Queen (Stephen Frears, 2006) and as a dame of the British Empire, coming across The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover. It's a full-fledged assault on conventional movies, so provocative that it feels like it was made a decade or so earlier, when filmmakers were testing the limits, and not in the comparatively timid 1980s. The title itself sounds like the setup for a dirty joke, but writer-director Peter Greenaway delivers much more than that. The Cook (Richard Bohringer) runs the kitchen at a fancy restaurant that has been taken over by the Thief (Michael Gambon) and his retinue of thugs, who make a mess of things every night. Meanwhile, the Thief's Wife (Mirren) is carrying on an affair with her bookstore-owner Lover (Alan Howard) in every nook and cranny of the restaurant they can find. When the Thief finds out, the lovers hide from him at the book depository, but the Thief finds and murders him by stuffing pages from books down his throat. Eventually, the Wife, with the culinary assistance of the Cook, takes revenge in a most unappetizing way. The whole thing is played in the most over-the-top fashion imaginable, but the skill and daring of the actors makes it compelling. Gambon makes the Thief so colossally vulgar that we laugh almost as much as we cringe. Mirren and Howard are naked for great stretches of the film, but the effect is less erotic than you might think; instead, it emphasizes their vulnerability. Add to that the extraordinary production design of Ben van Os and Jan Roelfs, the sometimes kinky costume design by Jean-Paul Gaultier, the cinematography of Sacha Vierny, and the musical score by Michael Nyman, and what you have is undeniably a work of art -- perverse and sometimes extremely unpleasant, but decidedly unforgettable.

Thursday, January 5, 2017

The Royal Tenenbaums (Wes Anderson, 2001)

Etheline Tenenbaum: Anjelica Huston

Chas Tenenbaum: Ben Stiller

Margot Tenenbaum: Gwyneth Paltrow

Richie Tenenbaum: Luke Wilson

Eli Cash: Owen Wilson

Raleigh St. Clair: Bill Murray

Henry Sherman: Danny Glover

Dusty: Seymour Cassel

Pagoda: Kumar Pallana

Ari Tenenbaum: Grant Rosenmeyer

Uzi Tenenbaum: Jonah Meyerson

Narrator (voice): Alec Baldwin

Director: Wes Anderson

Screenplay: Wes Anderson, Owen Wilson

Cinematography: Robert D. Yeoman

Production design: David Wasco

Film editing: Dylan Tichenor

Music: Mark Mothersbaugh

It's hard to be droll for an hour and a half, and The Royal Tenenbaums, which runs about 20 minutes longer than that, shows the strain. Still, I don't have the feeling with it that I sometimes have with Wes Anderson's first two films, Bottle Rocket (1996) and Rushmore (1998), of not being completely in on the joke. This time it's the wacky family joke, familiar from George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart's You Can't Take It With You and numerous sitcoms. It works in large part because the cast plays it with such beautifully straight faces. And especially because it's such a magnificent cast: Gene Hackman, Anjelica Huston, Ben Stiller, Gwyneth Paltrow, Luke Wilson, Owen Wilson (who co-wrote the screenplay with Anderson), Bill Murray, and Danny Glover. It's also beautifully designed by David Wasco and filmed by Robert D. Yeoman, with Anderson's characteristically meticulous, almost theatrical framing. Hackman, as the paterfamilias in absentia Royal Tenenbaum, is the cast standout, in large part because he gets to play loose while everyone else maintains a morose deadpan, but also because he's an actor who has always been cast as the loose cannon. Even in films in which he's supposed to be reserved and repressed, such as The Conversation (Francis Ford Coppola, 1974), he keeps you waiting for the inevitable moment when he snaps. Here he's loose from the beginning, but he doesn't tire you out with his volatility because he knows how much of it to keep in check at any given moment.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)