François Chevalier: Jean-Claude Drouot

Thérèse Chevalier: Claire Drouot

Émilie Savignard: Marie-France Boyer

Gisou Chevalier: Sandrine Drouot

Pierrot Chevalier: Olivier Drouot

Director: Agnès Varda

Screenplay: Agnès Varda

Cinematography: Claude Beausoleil, Jean Rabier

Film editing: Janine Verneau

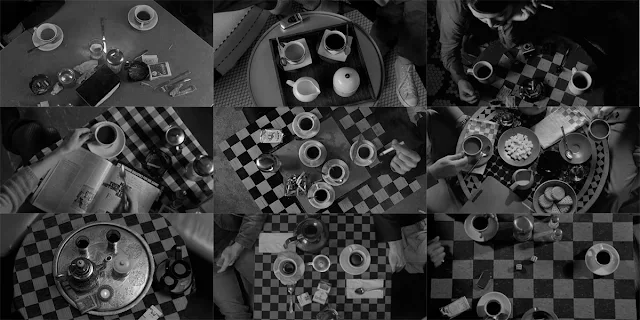

A summer idyll set to the music of Mozart -- what could be more charming and pleasant, especially when it's filmed in such ravishingly beautiful color? It features a handsome young working-class couple, François and Thérèse, and their two adorably well-behaved children. He's a carpenter, she's a dressmaker, and they are obviously blissful, taking the kids on excursions in the countryside where, while the little ones nap, they make love. Happiness indeed. And then he goes on a business trip and meets the very pretty Émilie who works in the post office and is about to move to the very Parisian suburb, Fontenay-aux-Roses, where François and Thérèse live. He agrees to build shelves in Émilie's new apartment and she becomes his mistress. This doesn't diminish his love for Thérèse, however. Indeed, it only increases his happiness. He's so happy, in fact, that Thérèse notices it and, one day when they're on an excursion to the countryside and the children are down for their naps again, she asks him why he has become so happy lately. After hedging for a few moments, he tells her the truth. He explains that they and the children are like an apple orchard in a field, and that one day he saw another apple tree growing outside the field, blooming along with them: "More flowers, more apples," he burbles. Thérèse not only seems to understand this analogy, but she and François then make passionate love. But at this point Agnès Varda's carefully crafted idyll turns savagely, searingly ironic -- which is what we should have known this portrait of an improbably perfect family was all along. With the aid of skillful photography and clever editing, Varda has crafted an enticing fable about sex, marriage, male egotism, and female enabling of it. Is the story tragic or comic? Is François a fool or a cad? Is Thérèse willfully blind? Is Émilie naive or wicked? How are we to take the film's ending, with its switch from summery to autumnal? There aren't many films that manage to be so satisfying and so tantalizing at the same time.

Watched on Filmstruck Criterion Channel