A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Tuesday, October 22, 2019

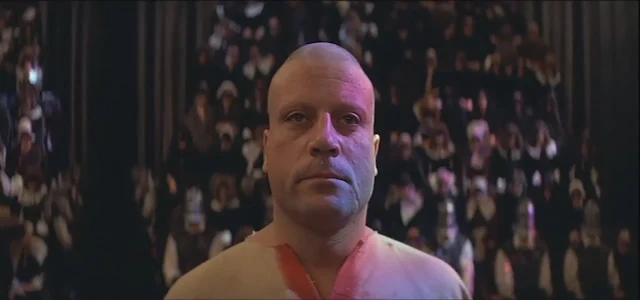

The Devils (Ken Russell, 1971)

The Devils (Ken Russell, 1971)

Cast: Oliver Reed, Vanessa Redgrave, Gemma Jones, Dudley Sutton, Max Adrian, Murray Melvin, Michael Gothard, Georgina Hale, Christopher Logue, Graham Armitage, Brian Murphy, John Woodvine, Andrew Faulds, Kenneth Colley, Judith Paris, Catherine Willmer, Izabella Telezynska. Screenplay: Ken Russell, based on a play by John Whiting and a novel by Aldous Huxley. Cinematography: David Watkin. Production design: Derek Jarman. Film editing: Michael Bradsell. Music: Peter Maxwell Davies.

Oliver Reed, the bad boy of British movies of the 1960s and '70s, seems an odd choice as the hero of The Devils, Urbain Grandier, the "hot priest" who inspires lust in an entire nunnery but also goes to the stake as a martyr to the cause of individual and religious freedom. He also gives the most controlled performance in a film in which everyone goes well over the top, including Vanessa Redgrave, who does a lot of seething and writhing as Sister Jeanne, the hunchbacked prioress of said nunnery. Glenda Jackson was originally thought of for the role, but turned it down because she didn't want to play another madwoman after Peter Brook's Marat/Sade (1967) and Russell's The Music Lovers (1971). I tend to sympathize with her: The Devils became a cause célèbre when the censors took offense at its nudity and supposed blasphemy, earning it an X rating in the United States and Britain, but today, when it would receive only a rather stern R, it feels more like the product of a director given to a kind of adolescent excess. There's a smirkiness in Russell's approach to what purports, in an opening title, to be a true story drawn from historical documentation. David Thomson has said that Russell "is oblivious of his own vulgarity and the triteness of his morbid misanthropy," which is taking it a bit further than I would. I think instead that Russell celebrates vulgarity, but not with any sense of irony about it, to the point that the luridness of The Devils becomes boring.

Monday, October 21, 2019

The Westerner (William Wyler, 1940)

|

| Barber/undertaker Mort Borrow (Charles Halton) looks for payment for his services in burying a man Roy Bean (Walter Brennan) has hanged. |

|

| Roy Bean faces a group of farmers who want to lynch him for his support of the cattlemen. |

|

| Cole Harden (Gary Cooper) intercedes with the farmers who want to hang Bean. |

|

| Bean buys up all the tickets for Lily Langtry's appearance, but is forced to deal with Harden instead. |

|

| Having managed to escape being hanged by Bean, Harden seeks safety among the farmers, including Wade Harper (Forrest Tucker) and Jane Ellen Mathews (Doris Davenport) and her father (Fred Stone). |

|

| Wearing his Confederate Army uniform, Bean awaits Lily Langtry's performance, only to be confronted by Harden. |

|

| The mortally wounded Bean meets his dream woman, Lily Langtry (Lilian Bond). |

|

| After a drinking bout, Harden wakes up in bed with the man who wanted to hang him. |

|

| Jane Ellen interrupts Bean's trial of Harden to protest against his brand of frontier justice. |

|

| Having persuaded Bean that he has a lock of Lily Langry's hair, Harden finds his hanging postponed. |

|

| Cattlemen burn out the homesteaders' settlement and kill Jane Ellen's father, but she vows to Harden that she'll stay. |

|

| Harden gives the supposed lock of Lily Langtry's hair to Bean. |

|

| Chill Wills (center) plays Southeast, one of the men who have brought Harden to Bean as a supposed horse thief. |

|

| Harden persuades Jane Ellen to let him cut a lock of her hair, which he intends to use to trick Bean. |

|

| Having settled down together, Jane Ellen and Harden watch more homesteaders arrive. |

The Westerner is something of a generic title, even for a genre film. I suppose it refers to Gary Cooper's Cole Harden, who is westering toward California when he's brought up short in Texas by some men who think he's a horse thief. (A horse thief sold him the horse.) Tried and sentenced under Judge Roy Bean's "law West of the Pecos," Harden manages to play on Bean's infatuation with Lily Langtry to con his way out of the predicament, only to be forestalled again by a pretty homesteader, Jane Ellen Mathews, played by Doris Davenport, whose career peaked with this film. She's quite good, but for some reason she failed to impress its producer, Sam Goldwyn, who held her contract. We are thick into Western movie tropes here: frontier justice, cowpokes vs. sodbusters, and so on. But what turns The Westerner into one of the classics of the genre is the good-humored attitude toward the material, displayed most of all in the performances of Cooper and Walter Brennan, whose Roy Bean won him the third and probably most deserved of his Oscars. But much credit also goes to that ultimate professional among directors, William Wyler, who doesn't condescend to the material but gives it a lovingly leisurely pace that allows his performers to make the most of it. And there's a screenplay that stays brightly on target from the moment Bean announces that "in this court, a horse thief always gets a fair trial before he's hung." Jo Swerling and Niven Busch got the credit (and the Oscar nomination) for the script, but some other formidable writers had a hand in it, including W.R. Burnett, Lillian Hellman, Oliver La Farge, and Dudley Nichols.

Sunday, October 20, 2019

Archipelago (Joanna Hogg, 2010)

Archipelago (Joanna Hogg, 2010)

Cast: Kate Fahy, Tom Hiddleston, Lydia Leonard, Amy Lloyd, Christopher Baker, Andrew Lawson, Mike Pender. Screenplay: Joanna Hogg. Cinematography: Ed Rutherford. Production design: Stéphane Collonge. Film editing: Helle le Fevre.

Rose (Amy Lloyd), a pretty young woman who has been hired to cook and clean for the Leighton family, is explaining to Edward (Tom Hiddleston) what she thinks is the humane way to cook a lobster. Don't plunge it directly into fully boiling water but instead put it in warm water and let the temperature slowly rise. The lobster will grow comatose and die in its sleep, she says. Sometimes, however, lobsters do struggle and try to get out of the pot, even knocking off the lid. I think there are audiences who may respond to Joanna Hogg's Archipelago like the lobsters: either drift off to sleep or decide to make an exit. For my part, I think it better to stay with it and behold the artistry with which Hogg steeps us in the building tensions of the family: mother Patricia (Kate Fahy), daughter Cynthia (Lydia Leonard), and son Edward. There's a father, too, but he is absent, and although he is expected to join them, there's a good deal of doubt about whether he will. They have leased a vacation home on one of the Isles of Scilly, an archipelago off the coast of Cornwall. Rocky, isolated, sparsely populated, but picturesque, the island, which the Leightons have visited before, has been chosen for a farewell celebration. Edward is about to go off to Africa to work as a health educator in an attempt to control the spread of AIDS, but it's soon apparent that there are tensions in the family over this altruistic decision -- and about many other things. Edward bears the brunt of most of the criticism, which comes largely from his sister, a bundle of nerves who likes to be in control at all times. We sense the tension between brother and sister from almost the beginning of the film, when Cynthia, who has arrived with her mother before Edward, offers a bit grudgingly to give up to Edward the bedroom she has already spent one night in and to move into one of the more cramped servant's rooms in the attic. Edward, not wanting to contest the issue, chooses the small, angular room, but the back-and-forthing among brother, sister, and mother foreshadows more power games to come. Like the master director she admires, Yasujiro Ozu, Hogg beautifully uses the setting, particularly the house, to heighten the emotions on display, even to the way a door is hung: The door to Cynthia's bedroom opens into the room, rather than against the wall, so that anyone entering has to sidle into Cynthia's presence, almost submissively. There is no door between the dining room and the kitchen, so when the family wants to discuss Edward's desire to ask Rose to dine with them, which Cynthia thinks inappropriate, they talk in hushed, tense, and nervous tones. Edward's rapport with Rose, to whom he often escapes from family tension, brings suspicion on him, even though he has a steady girlfriend back in London. Meanwhile, Patricia and Cynthia have a rapport with Christopher, an artist staying on the island who is giving them art lessons. It's a slow, talky film, not sweetened by a background music score, but it has a way of working itself into your brain with more emotional impact than films that pull out all the stops. The title, I think, is telling: Not only does it refer to where the film is set, but it also reminds us that while the islands in an archipelago are separate and distinct, they are geologically related and connected. No member of the Leighton family is an island entire of itself, though she or he may want to be.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)