A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Saturday, October 31, 2015

Still Alice (Richard Glatzer and Wash Westmoreland, 2014)

After four previous nominations, Julianne Moore was overdue for an Oscar. I just wish she had won for a more challenging film than Still Alice, a middlebrow, middle-of-the-road movie that unfortunately suggests a slicked-up power-cast version of a Lifetime problem drama. It goes without saying that, with her luminous natural style, Moore can act the hell out of anything she's given: When she played Sarah Palin in Game Change (Jay Roach, 2012) on HBO, she even made me forget Tina Fey's great caricature of that eminently caricaturable politician, and did it without resorting to caricature. What bothers me most about Still Alice is its choice of an affluent white professional, a linguistics professor with a physician husband (Alec Baldwin) and an attractive family, to carry the burden of what the movie has to say about Alzheimer's. Why couldn't the film have been about the effect of early-onset Alzheimer's on a black or Latino family, or someone faced with meeting the bills -- a waitress or a secretary or a factory worker, perhaps? The screenplay (by directors Glatzer and Westmoreland, from Lisa Genova's novel) even shamefully asserts at one point that the disease is particularly difficult for "educated" people. The movie has its good points, of course. Kristen Stewart, as Alice's younger daughter, is a revelation. I haven't seen any of the Twilight movies, but I gather that even those who have were startled by the skill and maturity of Stewart's performance. And the scene in which Alice discovers the suicide instructions left by herself before the disease had progressed is deftly handled, as the disease itself prevents Alice from remembering and following through on the instructions. The film also has some poignancy in the fact that director-screenwriter Glatzer, who was Westmoreland's husband, suffered from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and died from the disease in 2015. But I think the use in Still Alice of excerpts from Tony Kushner's Angels in America, suggesting a parallel between Alzheimer's and AIDS, is unfortunate.

Friday, October 30, 2015

A Clockwork Orange (Stanley Kubrick, 1971)

|

| Malcolm McDowell in A Clockwork Orange |

Dim: Warren Clarke

Georgie: James Marcus

Pete: Michael Tarn

Mr. Alexander: Patrick Magee

Mrs. Alexander: Adrienne Corri

Deltoid: Aubrey Morris

Catlady: Miriam Karlin

Minister: Anthony Sharp

Director: Stanley Kubrick

Screenplay: Stanley Kubrick

Based on a novel by Anthony Burgess

Cinematography: John Alcott

Production design: John Barry

Costume design: Milena Canonero

Film editing: Bill Butler

Any movie that was panned by Pauline Kael, Andrew Sarris, and Roger Ebert can't be all bad, can it? A Clockwork Orange remains one of Stanley Kubrick's most popular films, with an 8.4 rating on IMDb and a 90% fresh rating (93% audience score) on Rotten Tomatoes. I think it's a tribute to Kubrick that the movie can elicit such widely divergent responses. I can see what Kael, Sarris, and Ebert are complaining about while at the same time admitting that the film is undeniably entertaining in a "horrorshow" way: that being both novelist Anthony Burgess's Nadsat coinage from the Russian word "khorosho," meaning "good," and the English literal sense. For it is a kind of horror movie, with Alex as the monster spawned by modern society -- implacable, controlled only by the most drastic and abhorrent means, in this case a kind of behavioral conditioning. Watching it this time I was struck by how much the aversion therapy to which Alex is subjected reminds me of the attempts to convert gay people to heterosexuality. Which is not to say that Kubrick's film isn't exploitative in the extreme, relying on images of violence and sexuality that almost justify Kael's suggestion that Kubrick is a kind of failed pornographer. It is not the kind of movie that should go without what today are called "trigger warnings." What's good about A Clockwork Orange is certainly Malcolm McDowell's performance as Alex, one of the few really complex human beings in Kubrick's caricature-infested films. Some of his most memorable scenes in the movie were partly improvised, as when he sings "Singin' in the Rain" during his attack on the Alexanders, and when he opens his mouth like a bird when the minister of the interior is feeding him. Kubrick received three Oscar nominations, as producer, director, and screenwriter, and film editor Bill Butler was also nominated, but the movie won none, losing in all four categories to The French Connection (William Friedkin, 1971). It deserved nominations not only for McDowell, but also for John Alcott's cinematography and John Barry's production design.

Thursday, October 29, 2015

The White Sister (Henry King, 1923)

Watching Lillian Gish in a film directed by Henry King after seeing her as directed by D.W. Griffith, Victor Sjöstrom, and King Vidor is, to say the least, instructive. All four of these movies are romantic melodramas (though The Scarlet Letter is lightly touched by the greatness of Nathaniel Hawthorne's novel), but Griffith, Sjöstrom, and Vidor each possessed a degree of genius, whereas King will never be regarded as anything more than a director of solid competence. Despite his long career, which ranged from 1915 to 1962, amassing credits on IMDb for directing 116 films, his movies are not particularly memorable. Who, today, seeks out The Song of Bernadette (1943) or Wilson (1944), two of the "prestige" films he directed for 20th Century-Fox? In his great auteurist survey The American Cinema: Directors and Directions, 1929-1968, the best Andrew Sarris has to say about these and other movies directed by King is that they display a "plodding intensity." King was, in Sarris's words, "turgid and rhetorical in his narrative style," and that certainly holds true for The White Sister. Griffith, Sjöstrom, and Vidor all made use of Gish's rapport with the camera, her ability to suggest an entire range of emotions with her eyes alone -- hence the many close-ups she is given in their films. But King, filming on location in Italy and Algeria, is more interested in the settings than in the people inhabiting them. (Roy Overbaugh's cinematography is one of the film's virtues.) Nor does he seem interested in moving the story along, dragging it out to a wearisome 143 minutes. When Prince Chiaromonte (Charles Lane), the father of Angela (Gish) and her wicked half-sister, the Marchesa di Mola (Gail Kane), goes out fox-hunting, we're pretty sure that disaster is about to happen. But King stretches out the hunt so long that when Chiaromonte is killed the accident has no great emotional impact. And when Angela takes her vows as a nun, effectively preventing her from marrying Captain Severini (Ronald Colman), the man she loves but thinks is dead, King gives us every moment of the ceremony, trying to generate suspense by occasional cuts to Severini's ship steaming homeward. There's also an erupting volcano at the picture's end, but King fails to stage or cut it for real suspense. Gish is perfectly fine, though she's not called on to do much but look pious and to go cataleptic when Angela receives the news of Severini's supposed death. Colman is handsome but not much else, and Kane's villainy seems to be signaled by her talking out of the side of her mouth, as if channeling Dick Cheney many years in advance.

Wednesday, October 28, 2015

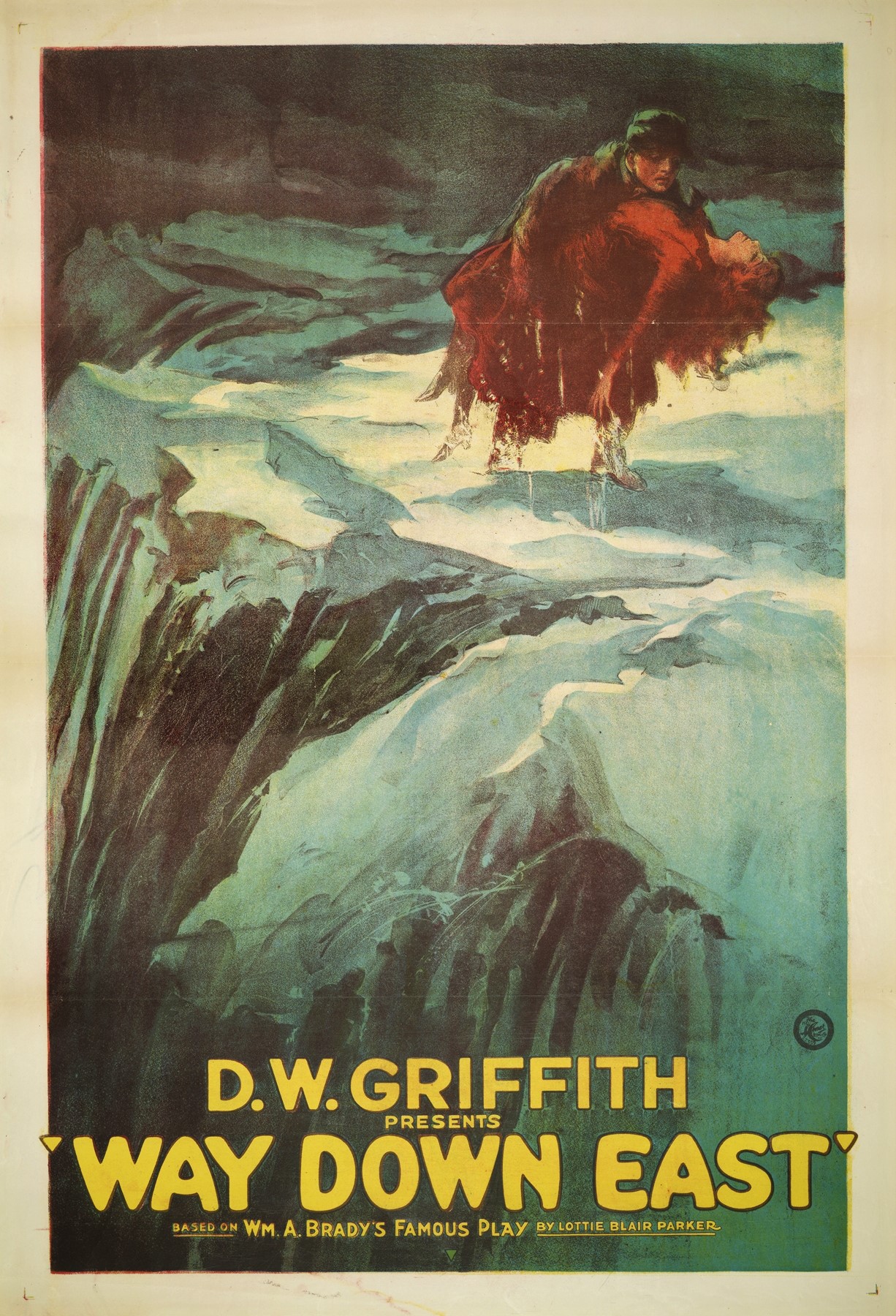

Way Down East (D.W. Griffith, 1920)

If Griffith's sententious title cards (e.g.,"Not by laws -- our Statutes are now overburdened by ignored laws -- but within the heart of man, the truth must bloom that his greatest happiness lies in his purity and constancy") don't have some viewers reaching for the remote, then the cornpone comic antics of his stereotypical rustics, such as the toothless constable (George Neville) and the hayseed Hi Holler (Edgar Nelson), certainly will. But stick with it to witness one of the great action sequences on film, Anna (Lillian Gish) adrift on the ice floe, as well as one of Gish's greatest moments as an actress, when she baptizes her dying baby. Yes, it's all hokum -- what do you expect from a melodrama almost a century old? But it's magnificent, enduring hokum, done brilliantly by a director who now seems more than just a pioneer but an artist of stature. And yes, that stature is tarnished by the man's racism in The Birth of a Nation (1915), just as Wagner's operas are tarnished by the anti-Semitism that many see lurking beneath their surface. But we don't have to endorse our artists to appreciate them, and the great efficiency with which Griffith tells a story and keeps us on the edge of our seats -- even when we know that his sentimentality is antique and outworn -- is something to be appreciated. Credit, too, must go to Billy Bitzer and the other cinematographers (Paul H. Allen, Charles Downs, and Hendrik Sartov) who gave us images that seem well beyond the years in which they were filmed. I do admit to some surprise that there are so many scenes in Way Down East that Griffith is content to film as if they were happening on a proscenium stage when one of his great contributions to the art of cinema is providing a fluidity and intimacy that are unavailable in the theater. Perhaps he was trying to do justice to his set designers, Clifford Pember and Charles O. Seessel, whose work is quite spectacular. But nothing before or since has quite equaled the ice floe sequence.

Tuesday, October 27, 2015

The Scarlet Letter (Victor Sjöström, 1926)

It's been many a year since I read The Scarlet Letter, but I'm pretty sure that any high school students who think they can get by watching Frances Marion's adaptation of it instead of reading Nathaniel Hawthorne's novel are likely to be disappointed in English class. That said, no film version is going to reproduce the depth of characterization, the symbolic force, or the intellectual density of Hawthorne, so we should be grateful for what this one does give us: one of Lillian Gish's greatest performances. This was Gish's second film for MGM, after La Bohème, and it suggests that her talents were better suited to a contemplative director like Victor Sjöström -- or Seastrom, as MGM insisted on anglicizing his name -- than to King Vidor's more action-oriented style. If her Mimi in La Bohème was disturbingly hyperactive, her Hester Prynne is a marvel of understated acting. She uses her eyes and mouth and the tilt of her chin to convey a miraculous range of emotions, from stubbornness to fear, from strength to frailty. It's a pity that her Dimmesdale, Lars Hanson, doesn't match her in subtlety. He's more successful in this regard in their 1928 collaboration The Wind, which was also directed by Sjöström.

Monday, October 26, 2015

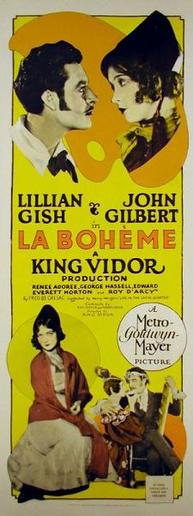

La Bohème (King Vidor, 1926)

Bohème without Puccini, except for a few themes from the opera interpolated into the piano accompaniment for the print shown on Turner Classic Movies. The screenplay by Fred De Gresac is said to be "suggested by Life in the Latin Quarter" by Henri Murger, which is also the source of the opera libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa. But since the librettists took liberties with Murger, combining several characters and incidents from his fiction, it's pretty clear that De Gresac was a good deal closer to the opera version than to Murger. It's very much a vehicle for Lillian Gish, who wanted John Gilbert to play Rodolphe to her Mimi, but sometimes seems to be playing an anything-you-can-do-I-can-do-better game with her co-star. There is, for example, a scene in which Gilbert acts out the proposed ending to the play he is writing, with much swashbuckling. Then, a few scenes later, Gish acts it out again with similar verve for a potential backer for the play. Their courtship is a surprisingly hyperactive one, particularly in the scene in which they and their fellow bohemians go on a picnic that involves much running about. And Gish is not content to die calmly: On hearing that she won't live through the night, she makes a mad dash across Paris to be reunited with her lover, at one point allowing herself to be dragged along the streets while hanging onto the back of a horse-cart. Gilbert poses with feet apart and arms akimbo once too often, and the starving bohemians are given to much dashing and dancing. (Among them is the endearing and enduring Edward Everett Horton as Colline.) It's all a bit too much, and I have a feeling that the TCM print is being shown at the wrong speed, giving it that herky-jerky quality we used to attribute to silent films before experts corrected the speed at which they should be projected. The costumes are by the celebrated designer Erté, who is said to have had so much trouble working with Gish that he gave up designing for Hollywood.

Sunday, October 25, 2015

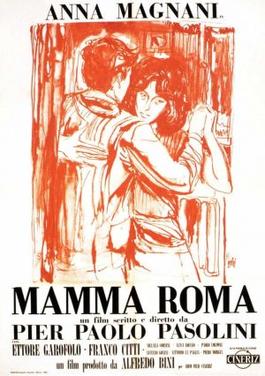

Mamma Roma (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1962)

Putting a force of nature like Anna Magnani in among the unknowns and non-professionals of the rest of the cast almost upends Pasolini's film, and it reportedly caused some friction between actress and director during the filming. If Pasolini really wanted the naturalistic Magnani of Rome, Open City (Roberto Rossellini, 1948) it was much too late: By then, she had won an Oscar for The Rose Tattoo (Daniel Mann, 1955) and had become the flamboyant, histrionic Magnani who shows up on-screen in Mamma Roma. That said, Pasolini certainly gave her every opportunity to present herself that way, starting with the opening scene in which she herds pigs into the wedding dinner of her former pimp, Carmine (Franco Citti), and culminating in one of the greatest scenes (or rather, pair of scenes) of her career. I mean, of course, the long-take tracking shot in which she walks down a Roman street at night, delivering a monologue on her life, as people appear out of the darkness and recede back into it, serving as interlocutors. It's stunning the first time Pasolini (aided by his cinematographer, Tonino Delli Colli) does it, and even more remarkable when he reprises it after a crisis in her life. I think Mamma Roma is some kind of great film, notwithstanding Pasolini's tendency to be somewhat heavy-handed in his symbolism: witness the staging of the wedding dinner as a parallel to Leonardo's The Last Supper and of Ettore (Ettore Garofalo) strapped to a restraining bed to echo Mantegna's painting of the dead Christ.

|

| Top: Ettore Garofalo in Mamma Roma. Below: Andrea Mantegna, Lamentation Over the Dead Christ, c. 1475-78 |

Saturday, October 24, 2015

The Grim Reaper (Bernardo Bertolucci, 1962)

The Grim Reaper suffers from some inevitable comparisons. Because it's a film in which police investigating a crime are given accounts by people with varying points of view, it's often compared to Rashomon (Akira Kurosawa, 1950), even though Bertolucci claims he hadn't seen that film before making his. Because it's based on a story by Pier Paolo Pasolini, who also worked on the screenplay with Bertolucci and Sergio Citti, and producer Tonino Cervi said he wanted the film made in the style of a Pasolini movie, Bertolucci, who had worked on Pasolini's first hit, Accatone (1961), was judged and found wanting accordingly. And finally, the film doesn't measure up to Bertolucci's later work, such as The Conformist (1970) and Last Tango in Paris (1972). But considering that Bertolucci was barely into his 20s when he made The Grim Reaper, it's an impressive film, with a deft use of unknown actors and atmospheric Roman locations. The episodes in which the suspects are interrogated and we see the events they testify about in flashback are linked by a sudden thundershower in each episode and by sequences in which the victim, a prostitute, gets ready to go out to her fatal assignation. It's not compelling filmmaking, but a significant start to a major career.

Friday, October 23, 2015

Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (Mike Nichols, 1966)

I don't know if Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? is a great play -- I've never seen it -- but it's not a great movie, perhaps because it sticks so closely to an uncinematic source. What it does have is one great performance, Richard Burton's, and one near-great one from Elizabeth Taylor. Unfortunately, George Segal and Sandy Dennis are miscast as Nick and Honey: He's too hip and she's too rabbity for their roles to take dramatic shape. Ideally, I think, Nick and Honey should be the conventional flies lured into George and Martha's sinister web. But as Mike Nichols directs them, they don't bring enough initial squareness to their parts, so their disintegration during the game-playing of their hosts happens too swiftly. What makes Burton's performance so memorable is his ability to shift moods, from sullen to mocking, from beleaguered to triumphant, in an instant. He also quite brilliantly suggests George's only barely latent homoerotic attraction to Nick, making it clear that he's titillated by the very idea of Martha's sleeping with the younger man. Taylor falters only in letting her Martha get too shrill for too long: A slower crescendo to her shrewishness would have been welcome in many scenes. Oscars went to Taylor and Dennis, but Burton lost to Paul Scofield in A Man for All Seasons (Fred Zinnemann, 1966) and Segal to Walter Matthau in The Fortune Cookie (Billy Wilder, 1966). Oscars also went to Haskell Wexler for black-and-white cinematography, Richard Sylbert and George James Hopkins for black-and-white art direction and set decoration, and Irene Sharaff for black-and-white costuming. This was the last year in which these categories were divided into color and black-and-white. It's sometimes observed that except for Cimarron (Wesley Ruggles, 1931), Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? is the only film to have received nominations in every category for which it was eligible. But it's likely that if the color/black-and-white division had been eliminated a year earlier, the film would have been shut out of some of these categories. Though he was a noted cinematographer, Wexler doesn't do his best work on Virginia Woolf, partly because Nichols, making his directing debut, called on him to do some close-up shots that not only don't hold focus but also distract from the essence of the drama, the interplay of its four characters. Nominations also went to Ernest Lehman as the film's producer and screenwriter, Nichols as director, George Groves for sound, Sam O'Steen for film editing, and Alex North for score. Oh, and if you're wondering why the title is sung to "Here We Go 'Round the Mulberry Bush" instead of "Who's Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?", essentially killing the joke, it's because the Disney studios, who owned the rights to the tune, wanted too much money.

Thursday, October 22, 2015

Wild Tales (Damián Szifrón, 2014)

We don't see the "anthology film" of the type represented by Wild Tales much any more, except in movies like Pulp Fiction (Quentin Tarantino, 1994) that take a group of somewhat interrelated stories and intercut them with one another. Damián Szifrón's movie is unabashedly a group of six short films that bear no essential relation to one another, except that they all deal with people at the breaking point and they all produce a macabre laughter. The movie was Argentina's entry in the best foreign language film category for the 2014 Oscars. (It lost to Pawel Pawlikowski's Ida.) Wild Tales takes off even before the credits with the mood-setting "Pasternak," in which a group of passengers on a plane all discover that, though they are strangers to one another, they are all in some unfortunate way acquainted with the plane's pilot who has ingeniously managed to get them on board together. (The pilot's murderous and suicidal intent is such an eerie foreshadowing of the May 2015 crash of Germanwings Flight 9525 that some theaters showing the film posted a warning.) My favorite of the episodes is "El más fuerte" ("The Strongest"), in which a road-rage incident snowballs to a deadly and hilarious conclusion reminiscent of a Warner Bros. cartoon in which Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck try to annihilate each other. My least favorite is probably the concluding one, "Hasta que la muerte nos separe" ("Until Death Us Do Part"), which depicts a wedding reception gone splendidly awry. It goes on too long, I think, but like all of the episodes it scores some satiric hits on its target, the wedding business. Other targets include the urban bureaucracy (everyone who has ever grumbled at the DMV will appreciate this one), the legal establishment, and the media's headlong rush to judgment.

Wednesday, October 21, 2015

American Sniper (Clint Eastwood, 2014)

|

| Bradley Cooper in American Sniper |

Taya Kyle: Sienna Miller

Marc Lee: Luke Grimes

Ryan "Biggles" Job: Jake McDorman

Dandridge: Cory Hardricht

Dauber: Kevin Lacz

Sheikh Al-Obodi: Navid Negahban

Jeff Kyle: Keir O'Donnell

Goat-Winston: Kyle Gallner

Director: Clint Eastwood

Screenplay: Jason Hall

Based on a book by Chris Kyle, Scott McEwen, and Jim DeFelice

Cinematography: Tom Stern

Film editing: Joel Cox, Gary Roach

I think American Sniper is not going to come into focus for us until 20 or 30 years have passed, and we have fully assessed the damage done by the American invasion of Iraq -- if, in fact, we ever do. Now, the only thing everyone seems to be able to agree on is that Bradley Cooper's powerful performance holds the film together. Otherwise, opinions about the movie range from those who see it as a reprehensible portrait of American arrogance to those who see it as a laudable portrait of American heroism. Most of us are somewhere in the middle, trying to decide whether it presents Chris Kyle as a victim of the Iraq incursion, as a misguided embodiment of false and outdated values, or as an archetype of the dutiful American military man. What it really seems to me is a muddle of all of these things because screenwriter Jason Hall and director Clint Eastwood can't bring the movie together into a satisfactory whole. It's wrong to review a movie that wasn't made, but I think American Sniper would have made a more coherent film if Chris Kyle's murder hadn't been relegated to a caption and shots of his funeral at the film's end. If the convergence of murderer and victim had been dealt with from the beginning, we might have had a more cohesive narrative about the effects of war on both those who can "handle it" and those who can't. As it is, we have only glances at large issues like simplistic world-view (Kyle's father's division of humankind into sheep, wolves, and shepherds), the American gun culture, the testosterone poisoning of machismo, the stereotyping of the enemy as "savages," and the inability of the United States to come to terms with the hidden problems of returning veterans. What we have instead are often exciting combat scenes mixed with rather clichéd domestic interludes. Sienna Miller does what she can with the underwritten and over-familiar role of the wife back home, but the script doesn't give her enough to work with. I admire Eastwood's restraint as a filmmaker, but I think it does him a disservice here. We are too close to the events of the first decade of the 21st century to have anything but our individual emotional reactions to them, and American Sniper is bound to ring false in some way to each of us. I kept thinking of Sergeant York (Howard Hawks, 1941) as I watched American Sniper. Made on the cusp of World War II, that unabashedly flag-waving movie about another American hero sharpshooter seems naive by contrast, even though the World War I in which Alvin York fought was at least as colossal an international fuck-up as the Iraq invasion, but it's also a better film. Maybe American Sniper will seem like a better film 74 years from now, but somehow I doubt it.

Tuesday, October 20, 2015

The Haunting (Robert Wise, 1963)

|

| Rosalie Crutchley in The Haunting |

Theodora: Claire Bloom

Dr. John Markway: Richard Johnson

Luke Sanderson: Russ Tamblyn

Mrs. Sanderson: Fay Compton

Mrs. Dudley: Rosalie Crutchley

Grace Markway: Lois Maxwell

Director: Robert Wise

Screenplay: Nelson Gidding

Based on a novel by Shirley Jackson

Cinematography: Davis Boulton

Production design: Elliot Scott

Film editing: Ernest Walter

Music: Humphrey Searle

The scariest thing in The Haunting is Rosalie Crutchley's smile. Crutchley was an English actress who exploited her deadpan mien, playing sinister and forbidding characters in scores of films and TV series. (I remember her fondly as the melancholy Judith Starkadder in the 1968 BBC production of Cold Comfort Farm that ran on Masterpiece Theatre in the States in 1971.) In The Haunting she plays the dour housekeeper of Hill House who warns the group of unwanted guests that she doesn't stay in the house at night, and that she won't be able to hear them if they cry out for her. Then she bids them good night with a monitory rictus of a smile. Otherwise, I find The Haunting more a study in missed opportunities than anything else. Things that go bump in the night are scary (except around my house, where it's likely to be one of the cats), but things that go wham, wham, wham! in the night, as they do in The Haunting, are more annoying than frightening. The music cues by Humphrey Searle constantly telegraph an upcoming scare, and the Hill House interior crafted by production designer Elliot Scott and set decorator John Jarvis is so fussily overdone that that it's distracting: I kept wondering what that tchotchke or that dado was instead of feeling threatened or oppressed by it. Worst of all, Nelson Gidding's screenplay gives us no character with whom we feel a strong emotional connection, essential if we are to fear for their lives. Eleanor Lance is supposed to be the film's central consciousness -- she is the one who arrives at the house first and is presented as the most physically and emotionally vulnerable -- but her hysterical voiceovers become tiresome. I haven't read the Shirley Jackson novel on which the film is based, and it's possible that she brings her characters more to life than Giddings and Wise do, but the whole premise of putting these people in a haunted house -- i.e., to do parapsychological research -- is bogus, no matter how often it's copied. I find it peculiar that the movie is celebrated as one of the most frightening of all time by people like Martin Scorsese and Steven Spielberg, who have ably demonstrated their own superior ability to scare us.

Monday, October 19, 2015

The Love Light (Frances Marion, 1921)

Watching Mary Pickford in The Love Light is exhausting. She is continuously on, rough-and-tumbling with her brothers, gamely sending them off to war, grieving their deaths, rescuing a sailor from drowning, hiding him from the villagers, flirting with him, discovering to her horror that he's a spy and that he may have made her the inadvertent cause of her brother's death, sending him off to the mercy of the villagers and his death. And just when it seems like she can't suffer (or act) any more, she has his baby (they were secretly married), goes mad and sees it adopted by another woman, gets it back, loses it again in a fiendish plot by the other woman, goes mad again, regains her sanity when her childhood boyfriend comes home from the war blinded, teaches him how to cope with his blindness, and eventually rescues her child from the clutches of the other woman by boarding the storm-tossed vessel in which the woman had tried to abduct the baby. It's one of those soaped-up melodramas we think of as typical of silent films, but it works, mostly because Pickford is amazing, but also because Frances Marion was such a skilled director and writer. Marion later became the first woman to win an Oscar for something other than acting, with her award for writing The Big House (George W. Hill, 1930), though by that time she had given up directing. (As a writer, the IMDb credits her with 188 titles, though some of those are remakes of her earlier films.) Still, it's primarily a showcase for Pickford's special brand of hard, determined acting. She resembles in her determination such later stars as Bette Davis and Joan Crawford, though they lacked Pickford's façade of softness (a softness masking steel). Davis would, of course, somewhat cruelly parody Pickford later in What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (Robert Aldrich, 1962). One great plus to The Love Light is the fine cinematography of Charles Rosher and Henry Cronjager.

Sunday, October 18, 2015

The Blot (Lois Weber, 1921)

|

| Louis Calhern and Claire Windsor in The Blot (Lois Weber, 1921) |

Saturday, October 17, 2015

Alice Guy-Blaché

|

| Alice Guy |

Friday, October 16, 2015

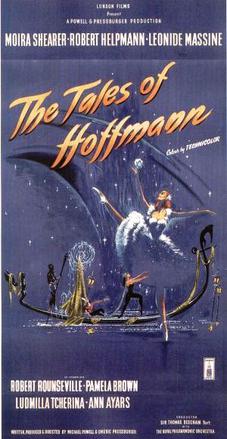

The Tales of Hoffmann (Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, 1951)

Opera and film are two well-nigh incompatible media, with different ways of creating characters, evoking mood, and telling stories. The handful of good opera films are those that find ways of replicating the operatic experience within a cinematic framework, the way Ingmar Bergman does in his film of Mozart's The Magic Flute (1975), which takes liberties with the original libretto and casts the action in a theatrical setting. The Powell-Pressburger Hoffmann also tinkers with the libretto, and with perhaps somewhat more justification: Offenbach didn't live to see his opera performed, and it exists in several variants. Opera companies rearrange and cut its various parts, and even interpolate music from other works by Offenbach. Like The Magic Flute, Hoffmann has fantasy elements that lend themselves to the special-effects treatment available to the movies, and Powell and Pressburger took full advantage. It is usually thought of as a companion piece to their film The Red Shoes (1948), in large part because it used many of the stars of that earlier film, including Moira Shearer, Robert Helpmann, Léonide Massine, and Ludmilla Tcherina, as well as production designer Hein Heckroth. The opera is sung in English, though the only singers who actually appear on screen are Robert Rounseville as Hoffmann and Ann Ayars as Antonia. Unfortunately, some of the singers whose voices are used aren't quite up to the task: Dorothy Bond sings both Olympia and Giulietta, and the difficult coloratura of the former role exposes a somewhat acidulous part of her voice. Bruce Dargavel takes on all four of the bass-baritone villains played on-screen by Helpmann, but his big aria, known as "Scintille, diamant" in the French version, lies uncomfortably beyond both ends of his range. Rounseville, an American tenor, comes off best: He has excellent diction, perhaps because he spent much of his career in musical theater rather than opera -- though he originated the part of Tom Rakewell in Stravinsky's The Rake's Progress in 1951. He is also well-known for his performance in the title role of Leonard Bernstein's Candide in the original Broadway production in 1956. It has to be said that the film is overlong and maybe over-designed, and that it sort of goes downhill after the Olympia section, in which Heckroth's imagination runs wild.

Thursday, October 15, 2015

A Matter of Life and Death (Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, 1946)

|

| David Niven and Marius Goring in A Matter of Life and Death |

Peter D. Carter: David Niven

June: Kim Hunter

Bob Trubshaw: Robert Coote

An Angel: Kathleen Byron

An English Pilot: Richard Attenborough

An American Pilot: Bonar Colleano

Chief Recorder: Joan Maude

Conductor 71: Marius Goring

Dr. Frank Reeves: Roger Livesey

Abraham Farlan: Raymond Massey

Director: Michael Powell, Emeric Pressburger

Screenplay: Michael Powell, Emeric Pressburger

Cinematography: Jack Cardiff

Production design: Alfred Junge

Fantasy, especially in British hands, can easily go twee, and though Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger had surer hands than most, A Matter of Life and Death (released in the United States as Stairway to Heaven, long before Led Zeppelin) still manages occasionally to tip over toward whimsy. There is, for example, the symbolism-freighted naked boy playing a flute while herding goats, the doctor's rooftop camera obscura from which he spies on the villagers, and the production of A Midsummer Night's Dream being rehearsed by recovering British airmen. And there's Marius Goring's simpering Frenchman, carrying on as no French aristocrat, even one guillotined during the Reign of Terror, ever did. Many find this hodgepodge delicious, and A Matter of Life and Death is still one of the most beloved of British movies, at least in Britain. I happen to be among those who find it a bit too much, but I can readily appreciate many things about it, including Jack Cardiff's Technicolor cinematography (Earth is color, Heaven black and white, a clever switch on the Kansas/Oz twist in the 1939 The Wizard of Oz) and Alfred Junge's production design. On the whole, it seems to me too heavily freighted with message -- Love Conquers Even Death -- to be successful, but it must have been a soothing message to a world recovering from a war.

Wednesday, October 14, 2015

The Confession (Costa-Gavras, 1970)

Ideologies are only as workable as the people who believe in them, which given the human drive toward power isn't very much. Costa-Gavras's film hasn't really dated much since its release 45 years ago. We are still faced with ideologues whose sole aim is to increase their own power in the name of some group or faction -- witness the current disarray of the Republican Party caused by the recalcitrance of the Tea Party faction in Congress. Which is not to say that the purge of John Boehner is anything as grave as the purges in the communist party in the Soviet Union under Stalin in the 1930s and in Czechoslovakia under Stalinist puppets in the 1950s. Yves Montand plays Gérard, a Czech communist official, based on a real figure, Artur London, who was accused of being a Trotskyite and a Titoist and of collaborating with American spies. He resisted torturous interrogation as long as possible before confessing. Sentenced to life imprisonment, he was released after serving several years in prison. The film ends with Gérard, still a disillusioned but hopeful communist, witnessing the 1968 Soviet crackdown against the "Prague Spring" reformists. It's an overlong but often effective movie, with fine performances by Montand, Simone Signoret as his wife, and Gabriele Ferzetti as the interrogator Kohoutek, a former Gestapo agent recruited by the communists to crack the people they want to purge.

Tuesday, October 13, 2015

A Lon Chaney Double Feature

He Who Gets Slapped, Victor Sjöström, 1924

The more I see of the young Norma Shearer, the more I like her. I recently watched The Student Prince in Old Heidelberg (Ernst Lubitsch, 1927), in which she's paired with Ramon Novarro, and was struck by how fresh and natural she was as an actress, and the same holds true in He Who Gets Slapped, where her love interest is John Gilbert. Both movies are silents, of course. It was only after the advent of sound that her husband, MGM's creative director Irving G. Thalberg, decided to make her into a great lady, the cinematic equivalent of Katharine Cornell, putting her into remakes of Broadway hits like The Barretts of Wimpole Street (Sidney Franklin, 1934), which had starred Cornell, or Strange Interlude (Robert Z. Leonard, 1932), which had featured another theatrical diva, Lynn Fontanne. She was also miscast as Juliet in Romeo and Juliet (George Cukor, 1936), a role that, at 34, she was much too old to play. She is barely in her 20s in He Who Gets Slapped, however, and she's delightful. This is not a film for coulrophobes (people with a fear of clowns), however. It's crawling with them, performing antics that are supposed to be, to judge from the hilarity they induce in the audiences shown in the film, side-splittingly funny. The film is based on the highly dubious premise that watching someone get slapped repeatedly is one of the funniest things ever. There may be people who think so -- to judge from the perennial popularity of the Three Stooges -- but I'm not one of them. The whole movie is an artificial concoction, anyway, and only the brilliance of Lon Chaney gives it some grounding in real-life feeling. It was one of the films that launched the MGM studios on the road to Hollywood dominance, and the first one to feature Leo the Lion in the credits.

Laugh, Clown, Laugh, Herbert Brenon, 1928

This is a grand showcase for Chaney, whose reputation as the man of a thousand faces was somewhat misleading. Chaney had one well-worn face that, no matter how much he distorted or disguised it, shone through. Here he's given an opportunity to perform without disguise through much of the film, and the range of expressions available to him is astonishing. The leading lady is 14-year-old Loretta Young. That she often looks her age is one of the more disturbing things about the film, in which she's supposed to be in love with both Chaney, who was 45, and the improbably pretty Nils Asther, who was 31. The cinematography is by James Wong Howe. Laugh, Clown, Laugh was eligible for Oscar nominations in the first year of the Academy Awards, and Chaney should have received one. The closest the film came to an award was the one that Joseph Farnham received for title writing (the one and only time the award was presented). But Farnham's award was for the body of his work over the nomination period, and not for a particular film.

Monday, October 12, 2015

House (Nobuhiko Obayashi, 1977)

This manic Japanese horror film has achieved something of a cult status. It was the feature film debut of its director, Obayashi, who began his career as a director of TV commercials, which shows in the film's continued barrage of brightly colored images and in the loud (and banal) pop music soundtrack. The story deals with a gaggle of Japanese schoolgirls (with nicknames that translate as "Gorgeous," "Fantasy," "Kung Fu," "Melody," "Prof," "Sweet," and "Mac") who find themselves trapped in a haunted house. They do a lot of running, yelling, giggling, screaming, and dying -- one of them is literally eaten by a grand piano. Ultimately, the film had a huge impact on music videos, but it remains a one of a kind movie experience -- for which some of us remain thankful while others of us relish yet another instance of the unfettered imagination of a Japanese artist. In this case, the imagination was not just that of the director but also of his pre-teen daughter, whose ideas about things that frighten children were worked into the screenplay. A great deal of credit (or blame, if you will) goes to production designer Kazuo Satsuya and cinematographer Yoshitaka Sakamoto.

Links:

House,

Kazuo Satsuya,

movies,

Nobuhiko Obayashi,

Yoshitaka Sakamoto

Sunday, October 11, 2015

Au Hasard Balthazar (Robert Bresson, 1966)

|

| Anne Wiazemsky in Au Hasard Balthazar |

Jacques: Walter Green

Gérard: François Lafarge

Marie's Father: Philippe Asselin

Marie's Mother: Nathalie Joyaut

Arnold: Jean-Claude Guilbert

Grain Dealer: Pierre Klossowski

Priest: Jean-Joel Barbier

Baker: François Sullerot

Baker's Wife: Marie-Claire Fremont

Gendarme: Jacques Sorbets

Attorney: Jean Rémignard

Director: Robert Bresson

Screenplay: Robert Bresson

Cinematography: Ghislain Cloquet

In his book Watching Them Be, James Harvey calls Au Hasard Balthazar "probably the greatest movie I've ever seen," and goes on to quote a number of others, including Jean-Luc Godard, who pretty much agree with him. I can't deny the movie's excellence, though I wouldn't quite go as far as Harvey does. It's a film that will try your patience unless you're willing to take Bresson on his own terms, which means not spelling anything out explicitly about his characters and their relationships. You're left to surmise a great deal about what they're doing and why. In fact, the only character in the film who gets a more or less fully fleshed-out story line is Balthazar himself, and he's a donkey. As usual, the performers are people we've never seen before on screen, and as usual with Bresson, that works out well, especially in the case of Anne Wiazemsky, who plays Marie. Only 19 when she made the film, she brings a freshness and vulnerability to her role that radiates through the deadpan non-acting that Bresson imposed on his performers. (The following year, she made La Chinoise with Godard -- which may help explain the extent of his enthusiasm for Balthazar -- and became his second wife after his divorce from Anna Karina.) I happen to be somewhat averse to films that center on animals, particularly if they carry the symbolic freight that Balthazar (whom one character refers to as "a saint") does, but even I couldn't help being touched by his story. This was Bresson's first film with Ghislain Cloquet as cinematographer, and the contrast with his previous film, The Trial of Joan of Arc (1962), shot by his longtime director of photography, Léonce-Henri Burel, is startling. Burel tended to follow Bresson's lead in providing austere images for austere stories, whereas Cloquet brings a romantic edge to his work. I think it only emphasizes the purity of Bresson's intentions.

Saturday, October 10, 2015

The Trial of Joan of Arc (Robert Bresson, 1962)

There are two great Joan of Arc films: The other one is Carl Theodor Dreyer's The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928). But comparing them is tricky: Dreyer's film was made in a different medium. Silent movies are not just movies without sound: They necessitate entirely different narrative techniques. Dreyer let the stunning quality of his images of the suffering Joan and the cruel and often grotesque interrogators and the crowd at her immolation do much of the business of characterizing and story-telling. According to an admirer of Bresson's, screenwriter-director Paul Schrader, Bresson disliked this about Dreyer's film, and it shows in the deliberate blandness of face and image in The Trial of Joan of Arc. The settings and costumes are generic and undistinguished, and they are lighted flatly, giving the film the banal look of the era's television dramas. As usual, Bresson has chosen unknown or non-professional actors, starting with his Joan, Florence Carrez. (Carrez was her mother's surname; she later took her father's surname, becoming Florence Delay, the name under which she became a successful novelist, playwright, and actress.) Compared to Renée Falconetti's magnificently haunting Joan in Dreyer's film, Carrez's performance is almost deadpan: She unemotionally responds to even the most provocative of her judges' questions, which Bresson took verbatim from the transcripts of the trial. On the whole, I think Bresson's austere style serves the material: When Carrez sheds a tear or even slightly raises her voice, it makes an emotional impact. By withholding so much dramatic visual information throughout the film, Bresson makes a few incidental moments the more powerful, as when we see a member of the crowd stick out a foot to trip Joan on the way to the stake, or when, as she is ascending the steps to the pyre, a small dog comes out of the crowd and stares up at her. On the whole, I prefer Dreyer's film, but I'm glad to have Bresson's as a contrast.

Friday, October 9, 2015

Pickpocket (Robert Bresson, 1959)

Maybe it's Bresson fatigue after watching three of his films in as many days (thanks to TCM's programming them in a block), but I found Pickpocket less satisfying than Diary of a Country Priest or A Man Escaped. What it does have going for it is a compelling central performance by another Bressonian unknown, Martin LaSalle, as Michel, the titular thief. LaSalle has the haunted look of the young Henry Fonda or Montgomery Clift -- a look, incidentally, that Alfred Hitchcock used to great effect by featuring those actors in two of his lesser-known films, Fonda in The Wrong Man (1956) and Clift in I Confess (1953). Pickpocket also contains a justly celebrated sequence demonstrating the team of thieves at work, a showcase for the work of Bresson's editor, Raymond Lamy. I think my mild dissatisfaction lies in Bresson's imposing his material on the structure of Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment. Like Raskolnikov, Michel lives in a cramped little garret room, meditates on the potential for a man of superior intellect to move beyond good and evil, commits a crime (though picking pockets is a good deal less evil than murdering an old woman) from which he refuses to benefit materially, gets caught, and is redeemed by his love for a "fallen woman," Jeanne (Marika Green), the film's equivalent to Dostoevsky's Sonya. The effect of all this is to make me wish that Bresson had simply decided to film Crime and Punishment. Lurking in the background as well are the existentialist novels of Camus and Sartre, which were much in vogue at the time.

Wednesday, October 7, 2015

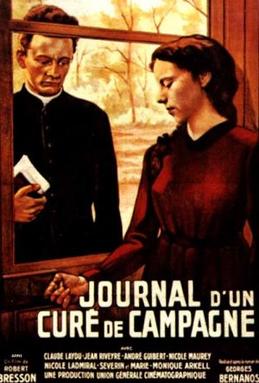

Diary of a Country Priest (Robert Bresson, 1951)

Of all the celebrated masterworks of film, Bresson's Diary of a Country Priest may be the most uncompromising in making the case for cinema as an artistic medium on the same level as literature and music. In comparison, what is Citizen Kane but a rather blobby melodrama about the rise and fall of a newspaper tycoon? Even the best of Hitchcock's oeuvre -- in which I would include Notorious (1946), Rear Window (1954), and North by Northwest (1959), while others would cite Vertigo (1958) and Psycho (1960) -- is little more than crafty embroidery on the thriller genre. The highest-praised directors, from Ford, Hawks, and Kurosawa to Godard, Kubrick, and Scorsese, never seem to stray far from the themes and tropes of popular culture. Even a film like Ozu's Tokyo Story (1953) falls back on sentiment as a way of engaging its audience. But Bresson strives for such a purity of character and narrative, down to the refusal to use well-known professional actors, and such a relentless intellectualizing, that you can't help comparing his film favorably to the great works of Flaubert or Dostoevsky. Having said that, I must admit that it's a work much easier to admire than to love, especially if, like me, you have no deep emotional or intellectual connection to religion -- or even an outright hostility to it. Does the suffering of the sickly young priest beautifully played by Claude Laydu really result in the kind of transcendence the film posits? Are the questions of grace and redemption real, or merely the product of an ideology out of tune with actual human experience? What explains the hostility he encounters in the village he tries to serve: the work of the devil or the bleakness of provincial existence? On the other hand, just asking those questions serves to point out how richly condensed is Bresson's drama of ideas. I love the movies I've cited above as somehow lacking in the intellectual seriousness of Bresson's film, but there's room in the pantheon for both kinds of film.

Tuesday, October 6, 2015

2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968)

Dave Bowman: Keir Dullea

Frank Poole: Gary Lockwood

HAL 9000: Douglas Rain (voice)

Director: Stanley Kubrick

Screenplay: Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C. Clarke

Based on a story by Arthur C. Clarke

Cinematography: Geoffrey Unsworth

Production design: Ernest Archer, Harry Lange, Anthony Masters

Monday, October 5, 2015

Amarcord (Federico Fellini, 1973)

Titta: Bruno Zanin

Gradisca: Magali Noël

Miranda: Pupella Maggio

Aurelio: Armando Brancia

Grandfather: Giuseppe Ianigro

Lallo: Nando Orfei

Teo: Ciccio Ingrassia

Oliva: Stefano Proietti

Director: Federico Fellini

Screenplay: Federico Fellini, Tonino Guerra

Cinematography: Giuseppe Rotunno

Production design: Danilo Donati

Music: Nino Rota

Nostalgia, Fellini-style, with lots of bawdiness, plenty of grotesques, much comedy, and a little pathos. It was a huge hit, earning the foreign-language film Oscar and nominations for Fellini as director and as co-author (with Tonino Guerra) of the screenplay. It's certainly lively and colorful, thanks to the cinematography of Giuseppe Rotunno, the production and costume design of Danilo Donati, and of course the scoring by Nino Rota -- though it sounds like every other score he did for Fellini. What it lacks for me, though, is the grounding that a central figure like Marcello Mastroianni or Giulietta Masina typically gave Fellini's best films, among which I would name La Strada (1954), The Nights of Cabiria (1957), La Dolce Vita (1960), and 8 1/2 (1963). The presumed center of Amarcord is the adolescent Titta, whose experiences over the course of a year in a village on Italy's east coast serve to link the various episodes together. But Titta is too slight a character to serve that function the way, for example, Moraldo (Franco Interlenghi) did as the Fellini surrogate in I Vitelloni (1953). There are some marvelous moments such as the sailing of the ocean liner SS Rex past the village, which goes out to greet it in a variety of fishing and pleasure boats. But too much of the film is taken up with the noisy squabbling of Titta's family, who soon wear out their welcome -- or at least mine.

Sunday, October 4, 2015

A Woman Is a Woman (Jean-Luc Godard, 1961)

|

| Jean-Claude Brialy and Anna Karina in A Woman Is a Woman |

Angela: Anna Karina

Alfred Lubitsch: Jean-Paul Belmondo

Director: Jean-Luc Godard

Screenplay: Jean-Luc Godard

Cinematography: Raoul Coutard

Production design: Bernard Evein

Music: Michel Legrand

Orson Welles is often quoted as having said, when he saw the production facilities available to him at RKO, "This is the biggest electric train set any boy ever had!" I imagine Jean-Luc Godard saying something like that when he was told that he could make his second feature film, after the success of Breathless (1960), in color and Franscope (an anamorphic wide-screen process like Cinemascope). But of course Godard and his cinematographer, Raoul Coutard, had no intention of using the wide screen for its conventional purpose, the epic and spectacular. Instead, many of the tricks the director and the cinematographer pulled off in A Woman Is a Woman were playful ones, like filming the tiny, cramped apartment of Angela and Émile in a medium more suited to Versailles. The effect is not only slightly giddy, but it also serves to emphasize the difficulties the couple are having in their relationship. The movie is brightly inconsequential, the kind of colorful musicalized nonsense that Jacques Demy would master a few years later with The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964) and The Young Girls of Rochefort (1967), using the same composer Godard does, Michel Legrand. The success of Breathless seems to have gone to Godard's head a bit: He enlists its star, Jean-Paul Belmondo, as the third leg of the movie's romantic triangle, and has him speak a line about not wanting to miss Breathless on TV. Belmondo also encounters Jeanne Moreau in a cameo bit, asking her how Jules and Jim is going -- Godard's fellow New Wave sensation, François Truffaut, was in the midst of filming it with Moreau. The best thing A Woman Is a Woman has going for it is Karina, who was about to become Godard's muse and for a while his wife.

Saturday, October 3, 2015

Alphaville (Jean-Luc Godard, 1965)

|

| Eddie Constantine in Alphaville |

Natacha von Braun: Anna Karina

Henri Dickson: Akim Tamiroff

Professor von Braun: Howard Vernon

Director: Jean-Luc Godard

Screenplay: Jean-Luc Godard

Cinematography: Raoul Coutard

Production design: Pierre Guffroy

Music: Paul Misraki

I think Alphaville may have been responsible for my former distaste for Godard movies: When I saw it on its first American run -- probably at that temple of Harvard hip, the Brattle Theater -- I couldn't figure out why anyone would make a sci-fi movie starring an American-French B-movie actor as a trenchcoated secret agent in a future that looked a lot like contemporary Paris. Or why the beautiful Natacha Von Braun should fall in love with anyone who looks like Eddie Constantine -- the apparent survivor of a close encounter with a cheese grater. But time and experience teach you a lot about what's really witty, and Alphaville is that. Yes, it's a spoof on both sci-fi and spy movies, with Paul Misraki's score providing the familiar dun-dun-DUNN! underscoring of suspenseful moments as Lemmy Caution slugs and shoots his way out of ridiculously staged confrontations. But how many spoofs have we seen that fall flat because they're so self-conscious about their spoofery? Godard's spoof succeeds because Constantine, Karina, and that great slab of Armenian ham Akim Tamiroff take their roles so seriously. Like most Godard movies, it's often absurdly talky, but the talk is provocative. And even though it seems to be designed to make a point about the way contemporary design and architecture have a way of alienating us from the human, it doesn't hammer the point. My one complaint in this recent viewing is that Turner Classic Movies showed a muddy print in which the subtitles had their feet cut off.

Friday, October 2, 2015

Masculin Féminin (Jean-Luc Godard, 1966)

In an intertitle during the film, Godard suggested that his portrait of French (or anyway Parisian) youth in the mid-1960s "could be called The Children of Marx and Coca-Cola." But the movie kept reminding me of Lena Dunham's portrait of American youth in the early 2010s, the TV series Girls, which might be called "The Children of Milton Friedman and Xanax." Godard's young Parisians find themselves in a time bursting with revolutionary energy but no particular channel in which to direct it other than sex and pop culture. The political activity of Godard's protagonist, Paul (Jean-Pierre Léaud), largely consists of pranks: distracting the driver of a parked military staff car so an accomplice can write an anti-war slogan along its side, and ordering a staff car on the phone under the guise of "General Doinel" -- a cheeky allusion to the role of Antoine Doinel, which Léaud played in The 400 Blows (1959) and four other films directed by François Truffaut. But most of the young people in the film are as shy of committing themselves to anything political or social as the beauty queen called "Mlle 19" (Elsa Leroy) whom Paul interviews at some length in one of the film's more spot-on satirical moments. This is a movie of fits and starts: moments of great energy interrupted by stretches of talk. As usual, Godard plays with viewers' expectations throughout, staging a sequence near the beginning in which a woman guns down her husband, only to ignore any follow-up action, and having a political protester immolate himself off-screen with only the somewhat indifferent reports of Paul and his girlfriend, Madeleine (Chantal Goya), as reactions to the event. The soundtrack is spiced with what sound like gunshots but turn out to be only billiard balls clashing against each other in a neighboring room. Some people dislike Godard because of his uncompromising resistance to conventional story-telling and scene-framing, and there is some rather self-conscious "movieness" about Masculin Féminin, as when the characters go to a film within the film and Paul has to make a special trip to the projection booth to complain that it's being shown in the wrong aspect ratio. But on the whole I find Godard's movies provide a necessary tonic against complacency.

Thursday, October 1, 2015

Pierrot le Fou (Jean-Luc Godard, 1965)

Roger Ebert did something critics seldom do: He changed his opinion of a movie. (Think about it: How many of us would like to be held to our original opinions of some films that were fun to watch the first time but haven't held up -- like, say, Braveheart (Mel Gibson, 1995) or Forrest Gump (Robert Zemeckis, 1994)?) Ebert gave Pierrot le Fou three and a half stars when he reviewed it in 1966, lauding Godard's "virtuoso display of his mastery of Hollywood genres." But in 2007, reviewing a re-release of the film, he reduced the assessment to two and a half stars: "I now see it," he wrote, "as the story of silly characters who have seen too many Hollywood movies." I think my opinion of the film might have been the reverse of Ebert's: If I had seen it 20 or 30 years ago, I might have dismissed it as a pretentious and arty example of the French New Wave at its worst, mixing silly antics with facile social and political satire. Instead, it now strikes me as a brilliant deconstruction of Hollywood film noir, gangster movies, and romantic adventure, almost perverse in its opening up of the traditional claustrophobic black-and-white atmosphere of noir with its bright wide-screen Eastmancolor images. And without Pierrot le Fou, or other Godard films like Breathless (1960) or Bande à Part (1964), would Hollywood have had the inspiration or the nerve to make movies like Bonnie and Clyde (Arthur Penn, 1967)? Yes, the characters played by Jean-Paul Belmondo and Anna Karina are silly, but Godard makes us see through their eyes the absurdity of the commerce-ridden milieu in which they exist. There is no core to their lives, no matter how much Ferdinand (Belmondo) and Marianne (Karina) may try to establish one with art and literature on his part or with a pursuit of fun on hers. The French have always loved to épater le bourgeoisie, and Godard plants himself firmly in that tradition, but the absurdity of Ferdinand's self-immolation (or -detonation), painting his face blue and wrapping his head in explosives, suggests that there is a price to be paid for shaking up the squares. But until we reach that point, Allons-y, Alonso!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)