|

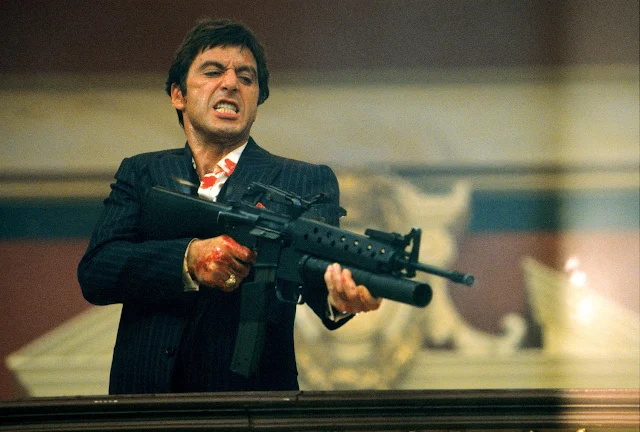

| Al Pacino in The Merchant of Venice |

Cast: Jeremy Irons, Joseph Fiennes, Lynn Collins, Al Pacino, Zuleikha Robinson, Kris Marshall, Charlie Cox, Heather Goldenhersh, Mackenzie Crook, John Sessions, Gregor Fisher, Ron Cook, Allan Corduner, Anton Rodgers, David Harewood, Antonio Gil.

Screenplay: Michael Radford,

based on a play by William Shakespeare.

Cinematography: Benoît Delhomme.

Production design: Bruno Rubeo.

Film editing: Lucia Zucchetti.

Music: Jocelyn Pook.

Michael Radford's

The Merchant of Venice is a respectable, almost satisfying version of an unsatisfying play. To put it mildly,

The Merchant of Venice has not worn well over time, especially in the post-Holocaust world, and not just because of the potential for anti-Semitic caricature in the presentation of the Jewish moneylender, Shylock. Taken as a whole, it's one of Shakespeare's most cynical plays, a portrait of mistrust, not only between Christians and Jews, but also between men and women, husbands and wives, old and young, rich and poor, and perhaps, if we adhere to the contemporary reading that seems to inflect Radford's version, between gay and straight. It's a play full of "othering." In that context, the play's two most familiar speeches, Shylock's "Hath not a Jew eyes" and Portia's "The quality of mercy is not strained" stand out, not as the homiletic antidotes to the prevalent mistrust in the play that they have often been taken to be, but as an ironic response to the omnipresent reality of avarice and prejudice that informs the play. Radford has done a good job of emphasizing the unsavory side of the mercantile life presented in the play. For all that Bassanio and Portia are embodiments of the traditional romantic hero and heroine of Shakespeare comedy, it also becomes clear that they enter into their relationship with less than noble sentiments: Bassanio needs money, which is why he goes to wive it wealthily in Belmont. Portia needs to be relieved of the absurd burden imposed by her late father's will, which leaves to blind chance the identity of her future husband. Radford also underscores the fact that the real love match of the play is between two men, Antonio and Bassanio, with the former willing to risk his fortune and eventually his life for the latter, whereas Bassanio can't even be bound not to part with the ring Portia has given him. It's a queer play indeed. The film is full of good performances, starting with Al Pacino's as Shylock, perhaps the

raison d'être of the film. The part could have brought out Pacino's worst scenery chewing, but he reins himself in to emphasize the long-suffering Shylock, not the bloodthirsty Shylock, and in the end makes the character less stereotypically avaricious. Jeremy Irons is most effective when he shows Antonio's increasing awareness that he has been trapped, partly at least by his love for Bassanio. Joseph Fiennes is less effective as the wooer of Portia than he is as the stalwart friend of Antonio, but that's partly because Lynn Collins maintains Portia as the upper hand in their relationship -- so much so, that we might wonder what she sees in him. Radford has trimmed and rearranged some of the play, downgrading its great purple passage, Lorenzo's speech to Jessica that opens the somewhat anticlimactic Act V, "How sweet the moonlight sleeps upon this bank." In fact, he gives the opening lines of the speech to an off-screen singer, and lets Lorenzo pick up with "Look how the floor of heaven / Is thick inlaid with patines of bright gold." It's a sacrifice of poetry for the sake of drama, and I won't complain. There's poetry enough in the handsome production design and cinematography, full of echoes of Renaissance art.