The influence of American movies on the work of Akira Kurosawa is well-known. His viewings of American Westerns, for example, helped shape such classics as

Seven Samurai (1954) and

Yojimbo (1961). But

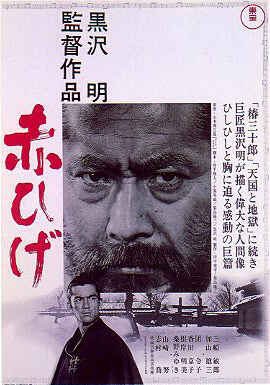

Red Beard seems to me an instance in which the influence wasn't so fortunate. It's a kind of reworking of MGM's series of

Dr. Kildare movies of the 1930s and '40s, in which the ambitious young intern Dr. Kildare tangles with the crusty older physician Dr. Gillespie and thereby learns a few lessons -- a dynamic that persists today in TV series like

Grey's Anatomy and soap operas like

General Hospital. In

Red Beard, ambitious young Dr. Noboru Yasumoto (Yuzo Kayama) is sent to work under crusty older Dr. Kyojo Niide (Toshiro Mifune), known as "Red Beard" for an obvious facial feature. It's the 19th century, the last years of the Tokugawa shogunate, and Yasumoto, having finished his studies in Nagasaki, expects that the influence of his father, a prominent physician, will land him a role as the shogun's personal physician. He's angry when he finds that he's been sent to a rural clinic that mainly serves the poor. There is one affluent patient at the clinic, however: a young woman known as "The Mantis" (Kyoko Kagawa) because she stabbed two of her lovers to death. Her wealthy father has built a house for her on the grounds of the clinic, but only Red Beard is allowed to approach and treat her. Yasumoto initially rebels against the assignment, feeling disgust for the patients: When he asks the physician he's replacing at the clinic what smells like "rotten fruit," he's told that that's the way the poor smell. But eventually (and predictably), he learns to respect the work of Red Beard and to value the lives of his patients.

Red Beard is hardly a bad movie: Kurosawa brilliantly stages the first encounter of Yasumoto and The Mantis, who has escaped from her house, in a carefully framed sequence, a long take in which the doctor and the madwoman begin at opposite sides of the wide screen -- it's filmed in Tohoscope, an anamorphic process akin to Cinemascope -- with a tall candlestick between them. Gradually, accompanied by slow camera movements, the two approach each other, the doctor trying to gauge the motives and the sanity of the young woman. Finally the calm framing of the scene is shattered into a series of quick cuts, as she attacks with a pair of scissors, and the scene ends with a brief shot of Red Beard suddenly opening the door.

Red Beard was shot by two acclaimed cinematographers, Asakazu Nakai and Takao Saito, both of whom frequently worked with Kurosawa, and the production design was by Yoshiro Muraki, who fulfilled Kurosawa's exacting demands for meticulous faithfulness to the period, including the construction of what was virtually a small village, using only materials that would have been available in the period. But what keeps

Red Beard from the first rank of Kurosawa's films, I think, is the sentimental moralizing, the insistence of having the characters "learn lessons." Yasumoto, having learned his initial lesson about valuing the lives of the poor, is given a young patient, Otoyo (Terumi Niki), rescued from a brothel where she has essentially gone feral. (During the rescue scene, Kurosawa can't resist having his longtime star Mifune show off some of his old chops: The doctor takes on a gang of thugs outside the brothel and single-handedly leaves them with broken arms, legs, and heads. It's a fun scene, but not particularly integral to the character.) When Yasumoto has succeeded in teaching Otoyo to respond to kindness, it then becomes her turn to teach others what she has learned. The moralizing overwhelms the film, leaving us longing for the deeper insight into the characters found in films by Kurosawa's great contemporaries Yasujiro Ozu and Kenji Mizoguchi.