Sometimes linked with Hour of the Wolf (1968) and Shame (1968) as a third element of a trilogy set on Fårö island, Ingmar Bergman's The Passion of Anna is a characteristically intense working out of themes of grief and guilt, involving two couples whose lives intersect against a backdrop of mysterious instances of cruelty toward animals. I find it one of Bergman's more forgettable films, but it has strong admirers.

A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Liv Ullmann. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Liv Ullmann. Show all posts

Tuesday, June 4, 2019

The Passion of Anna (Ingmar Bergman, 1969)

Monday, October 9, 2017

Shame (Ingmar Bergman, 1968)

|

| Liv Ullmann and Max von Sydow in Shame |

Jan Rosenberg: Max von Sydow

Jacobi: Gunnar Björnstrand

Mrs. Jacobi: Brigitta Valberg

Filip: Sigge Fürst

Lobelius: Hans Alfredson

Director: Ingmar Bergman

Screenplay: Ingmar Bergman

Cinematography: Sven Nykvist

Production design: P.A. Lundgren

Film editor: Ulla Ryghe

One of Ingmar Bergman's bleakest and best films, Shame is unencumbered by the theological agon that makes many of his films tiresome (not to say irrelevant) for some of us. It's a fable about a couple, Eva and Jan, two musicians seeking to escape from a devastating war by exiling themselves to an island. At the start of the film their life is almost idyllic: Their radio and telephone don't work, so they remain in blissful ignorance of the problems of the world outside. He's a bit scattered and idle; she's practical and businesslike. They quarrel a little over their temperamental differences, but they have developed a self-sustaining life, raising chickens and cultivating vegetables in their greenhouse. But needless to say, no couple is an island: The war comes to them. When they take the ferry into town, selling crates of berries and stopping to drink wine with a friend who has just been drafted, they begin to be aware that the larger conflict will not remain at a distance for long. There will be no retreat for them into the simple life. Under the pressure of war, their relationship changes: Eva becomes more careless, Jan loses his passivity. In the end, desperate to flee the despoiled island, they join a group on a fishing boat heading for the mainland only to wind up in a dead calm -- a literal one, for they are stuck in a sea filled with corpses, an image that, because so much of the film is straightforward in narrative and imagery, manages to avoid the heavy-handedness that often afflicts Bergman's films. There is also, for Bergman, a surprising lack of specificity about the war in the film: There are no direct allusions to particular wars, such as World War II, the one that raged in his childhood, or to the war of the day in Vietnam -- there are no images of burning monks as in Persona (1966). The war of the film is generic -- soldiers, planes, trucks, and tanks lack insignia and the names and nationalities of the two sides are never mentioned. It's as if war is an ongoing condition of the human race.

Monday, June 5, 2017

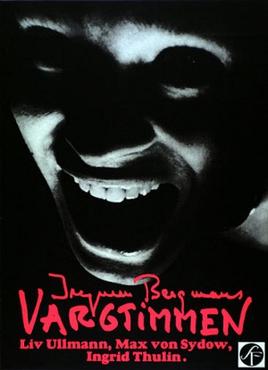

Hour of the Wolf (Ingmar Bergman, 1968)

Ingmar Bergman's Hour of the Wolf is unquestionably a "horror movie" -- i.e., one filled with incidents and images and narrative details aimed at shocking the viewer. It takes place on a remote island with a mysterious castle. Figures appear who may be either humans or demons. There's a scene in which a man walks up the wall and across the ceiling and one in which a woman peels off first her wig and then her face. The protagonist either murders or imagines that he has murdered a small boy. That protagonist is Johan Borg (Max von Sydow), an artist, who has come to the island with his wife, Alma (Liv Ullmann), to recover after an illness -- physical or mental, we're not told. Johan can't sleep, and Alma sits up with him at night while he tells her about the demons whose images he has sketched, so no wonder that her own mental state becomes fragile. One day, she meets an old woman who tells her that she should read Johan's diary, which he keeps under his bed. She does so, rather like Bluebeard's wife persisting in opening his castle's doors, uncovering some disturbing entries regarding his continued obsession with an old love, Veronica Vogler (Ingrid Thulin). They're invited to a dinner party at the castle by the baron (Erland Josephson), where they meet a variety of unlovely sophisticates and are entertained by a rather bizarre puppet show excerpt from Mozart's The Magic Flute (an opera that Bergman would film, in a less bizarre manner, seven years later). But the climax of the evening comes when the baroness (Gertrud Fridh) takes the Borgs to her bedroom to show off her prized possession: Johan's portrait of Veronica Vogler. From then on, it's a deep descent into madness for Johan and a desperate attempt by Alma to save both of them from self-destruction. The "creep factor" in Bergman's movies is never entirely missing, but Hour of the Wolf cranks it up higher than ever. The problem is that the creepiness is sustained almost to the point of tedium, and with a concomitant loss of credibility. The remote island setting prevents the film from grounding itself in normality, so that the action plays out on one sustained note of oppressive isolation. Hour of the Wolf has many admirers, who rightly point out that Bergman, with the considerable help of his actors and his cinematographer, Sven Nykvist, has crafted a nightmare of erotic obsession with the utmost skill. But I like to compare Hour of the Wolf to another horror movie released the same year, Roman Polanski's Rosemary's Baby, a "commercial" product aimed at a general audience, which suggests evil things going on beneath the surface of a commonplace urban setting, and ask which is the more successful: the sustained psychological oppressiveness of the Bergman film or the sinister mixture of comedy and shock of the Polanski movie?

Tuesday, April 12, 2016

Persona (Ingmar Bergman, 1966)

There comes a time in the history of any art when the pressure to do something new is exceeded by the difficulty of finding that newness. I think Persona is a good example of that problem. By the mid-1960s we had seen the great innovations in filmmaking of Buñuel, Antonioni, Resnais, and Godard, among many others. So when Ingmar Bergman chooses to open Persona with a montage of apparently random images, or chooses to dwell on images of self-immolating Buddhist monks during the Vietnam war or children being rounded up by the Gestapo, or to repeat an entire scene, or to resort to a kind of Verfremdungseffekt by showing the director and his crew filming the scenes we're watching, we can mutter to ourselves, "Seen that one before." The remarkable thing is that none of this apparently derivative film and narrative technique seriously weakens the movie, which is one of Bergman's best. Even though we can dismiss the killing of the sheep in the opening montage as a kind of homage to (or borrowing from) Buñuel's Un Chien Andalou (1929), or point at the opening of Resnais's Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959) as another example of such a montage, or cite Godard's political engagement as a precursor of Bergman's use of Vietnam and the Holocaust in his film, none of that really matters. Persona stands firm on its own, largely because of the phenomenal performances of Bibi Andersson as Alma and Liv Ullmann as Elisabet, and the extraordinary art of Sven Nykvist's black-and-white cinematography. The only other film in Bergman's opus that seriously challenges it for primacy, I think, is Cries and Whispers (1972), and that largely because Bergman had by that time realized that innovation could be a dead end and that concentrating on story and character without cinematic tricks was all that was needed to make a successful film. The core of Persona lies in the fascinating, ever-shifting relationship between the mute Elisabet and the garrulous Alma, and we don't even need the sequence in which the images of the two actresses merge into one to get the point. It's sometimes said that the film works because Andersson and Ullmann look so much alike, but they really don't. Andersson has a kind of conventional prettiness: As I noted in my entry on The Devil's Eye (Bergman, 1960), she could almost pass as the heroine of a 1960s American sitcom like Donna Reed or Elizabeth Montgomery. Ullmann has a stronger face: a more determined gaze, powerful cheekbones, a fuller, more sensuous mouth. The two women could not have exchanged roles in the film without a serious disruption in their relationship: Even though she's three years younger than Andersson, Ullman has to play the mature, successful actress, and Andersson the eager young nurse. What gives their relationship in the film its marvelous tension is the sense that Alma is imbibing, in an almost vampiric way, the strength that Elisabet possessed before her onstage breakdown. Part of me wishes that Bergman had had the conviction to tell the two women's stories without the narrative gimmicks, but another part tells me that Persona has to be judged for what it is, and that it's one of the great films.

Links:

Bibi Andersson,

Ingmar Bergman,

Liv Ullmann,

Persona,

Sven Nykvist

Wednesday, March 30, 2016

Scenes From a Marriage (Ingmar Bergman, 1973)

|

| Erland Josephson and Liv Ullmann in Scenes From a Marriage |

Thursday, March 17, 2016

Cries and Whispers (Ingmar Bergman, 1972)

Cries and Whispers is both of a time and timeless. It is very much a product of the last great moviegoing age, when people would see a challenging film and go back to their homes or coffee shops or dorm rooms and debate what it meant. Today, if a movie provokes discussion it's usually on social media, where seriousness gets short shrift. Moreover, the discussion is likely to get interrupted by someone who has just seen the latest installment of some hot TV series and wants to try out their theories. Moreover, the combination of visual beauty and emotional rawness in Bergman's film is something rarely encountered today. We are, I think, wary of emotion, too eager to lapse into ironic distancing from the depiction of disease, suffering, death, cruelty, passion, spite, and grief that permeates Cries and Whispers. No director I know of is trying to do what Bergman does in so unembarrassed a fashion in this movie. And that, in turn, is what makes it timeless: The emotions on view in the film are universal, and Bergman's treatment of them without melodrama or sentiment is unequaled. Personal filmmaking is becoming a lost art: There are a few prominent adherents to it today, such as Paul Thomas Anderson or Terrence Malick, and their films are usually greeted with a sharp division of opinion between critics who find them pretentiously self-indulgent and those who find them audaciously original. But we seldom see performances as daring as Harriet Andersson's death scene, Kari Sylwan's attempts to comfort her, Ingrid Thulin's self-mutilation, and Liv Ullmann's confrontations with the others. And we seldom see them in a narrative that teeters between realism and nightmare as effectively as Bergman's screenplay, in a setting so evocative as production designer Marik Vos-Lundh's, or via such sensitive camerawork as Sven Nykvist's. The film has often been compared to Chekhov, and for once it's a film that merits the comparison.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)