|

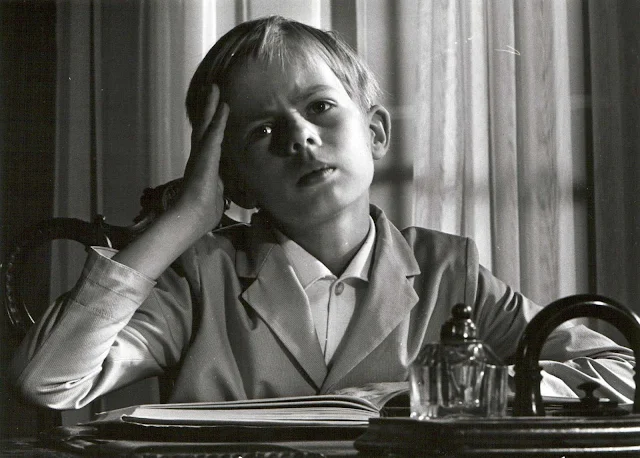

| Jarl Kulle in All These Women |

Cornelius: Jarl Kulle

Humlan (Bumblebee): Bibi Andersson

Isolde: Harriet Andersson

Adelaide: Eva Dahlbeck

Madame Tussaud: Karin Kavli

Traviata: Gertrud Fridh

Cecilia: Mona Malm

Beatrica: Barbro Hiort af Ornäs

Jillker: Allan Edwall

Tristan: Georg Funkquist

The Young Man: Carl Billquist

Director: Ingmar Bergman

Screenplay: Erland Josephson, Ingmar Bergman

Cinematography: Sven Nykvist

Production design: P.A. Lundgren

Film editing: Ulla Ryghe

Roger Ebert called Ingmar Bergman's All These Women "the worst film he has ever made," and I don't think it's because the butt of so many of the jokes in the movie was a critic. It's an arch, highly stylized comedy, supposedly inspired by Federico Fellini's

8 1/2 (1963), though apart from the zings at critics and the gathering together of the various women in an artist's life, there's not much that Bergman's film has in common with Fellini's. Bergman's artist, a cellist named Felix, has just died, and the film opens at his funeral through which a number of his "widows" parade to view the corpse. The funeral is presided over by Cornelius, Felix's supposed biographer, actually a music critic who was trying to persuade Felix to perform one of his compositions: "A Fish's Dream, Abstraction #4." The film flashes back to the days before Felix's death when Cornelius arrived at the cellist's estate and encountered his wife, Adelaide; his mistress, called "Bumblebee"; and several other women who had various connections, presumably sexual, to Felix. What follows is much running about, some slapstick, some misfired attempts by Cornelius to bed Bumblebee while trying to gather information about Felix's private life, and much tiresome and unfunny ado set to music cues ranging from Bach to "Yes, We Have No Bananas."

All These Women was Bergman's first film in color, but the print shown on Turner Classic Movies is sadly faded, with captions that are hard to read. I also sampled the print on the Criterion Channel; it's better, but still rather washed-out looking. The cinematographer, Sven Nykvist, is a celebrated master, so the color flaws may be that of the aging Eastmancolor negative. Only the fact that the film is a lesser work of the director who gave us

The Seventh Seal (1957),

Persona (1966), and

Fanny and Alexander (1982) really argues for restoring it, however.