A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Friday, April 22, 2016

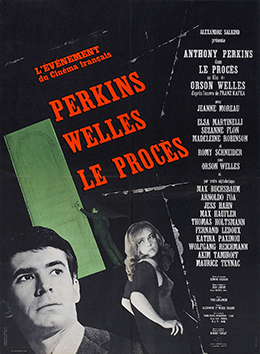

The Trial (Orson Welles, 1962)

There may be sensibilities more different from each other than those of an exiled Midwestern bon vivant and a consumptive Middle European Jew, but they rarely come together in a work of art the way they did in Orson Welles's version of Franz Kafka's The Trial. It was made in that fertile middle period of Welles's career that also saw the creation of Touch of Evil (1958) and Chimes at Midnight (1965), and it holds its own against those two landmarks in the Welles oeuvre. In the end, of course, the Wellesian sensibility dominates, the American tendency to affirmation overcoming (barely) Kafka's pessimism: Welles's Josef K. (Anthony Perkins) is rather more assertive than Kafka's protagonist. He doesn't succumb "Like a dog!" to his assailants but defies them. That said, Perkins, now carrying the indelible stamp of Norman Bates into all his roles, is superlative casting: We can believe that he's guilty -- even if we never find out what his supposed crime is -- while at the same time we sympathize with his plight. The real triumph of the film is in finding the settings in which to stage K.'s ordeal, ranging from K.'s stark, low-ceilinged apartment to bleak modern high-rise apartment and office buildings, to ornate beaux arts exteriors, to the labyrinthine courts of the law. The film was shot in the former Yugoslavia, in Italy, and in the abandoned Gare d'Orsay in Paris. Welles chose a novice, Edmond Richard, who had never shot a feature film, as his cinematographer. Richard went on to shoot Chimes at Midnight, too, as well as some of Luis Buñuel's best films, including The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972). The cast includes Jeanne Moreau, Romy Schneider, Elsa Martinelli, and Akim Tamiroff, with Welles himself playing the role of Hastler, K.'s attorney, after failing to persuade Jackie Gleason or Charles Laughton to take the part. The Trial is probably longer and slower than it needs to be, and there is some inconsistency of style: The scenes involving Hastler, his mistress (Schneider), and K. are shot with more extreme closeups than the rest of the film, where the sets tend to overwhelm the human figures. And the ending, with its explosion followed by a rather wispy mushroom cloud, is a little too obviously an attempt to bring a story written during World War I into the atomic era. Some think it's a masterpiece, but I would just rank it as essential Welles -- which may or may not be the same thing.

Thursday, April 21, 2016

Alice in the Cities (Wim Wenders, 1974)

|

| Yella Rottländer and Rüdiger Vogler in Alice in the Cities |

Alice: Yella Rottländer

Lisa: Lisa Kreuzer

Director: Wim Wenders

Screenplay: Wim Wenders, Veith von Fürstenberg

Cinematography: Robby Müller

Film editing: Peter Przygodda

The Alice of Wenders's movie, played by 9-year-old Yella Rottländer, is not the plucky Victorian girl of Lewis Carroll's books, but I think they might recognize one another. Both find themselves cast adrift in a strange world in which what little guidance they have is decidedly eccentric. In Wenders's film, Alice has come to America with her mother, Lisa, who is caught up in a relationship that's not working out. Having decided to return to Germany, Alice and Lisa find themselves at a ticket counter with a German writer, Philip, who is also going home after flubbing an assignment to tour the States and write about his experiences. Flights to Germany have been canceled by an air traffic controllers' strike, but Philip helps Lisa book tickets on the same flight he's taking to Amsterdam, where they hope to make it home by ground transportation. Because Lisa speaks no English, he also helps her book a hotel room that he ends up sharing with them. And then Lisa decides to make one last effort to connect with her boyfriend, and leaves Alice with Philip, saying that she'll meet them in Amsterdam. Which she doesn't do. Philip, a cranky egotistical loner, now has a 9-year-old girl on his hands. Moreover, she hasn't lived in Germany for several years and remembers only that she has a grandmother whose name she doesn't know but who she thinks might live in Wuppertal. And off this unlikely pair goes on an oddball odyssey. What makes the film work is Wenders's lack of sentimentality, Rüdiger's depiction of Philip's gradually eroding self-centeredness, and Rottländer's entirely natural portrayal of a child in search of roots that she has never been taught she should have. It's shot in a documentary style by Robby Müller, who captures Philip's experience in an America where every place -- gas stations, fast-food joints, cheap motels -- tries to look like every other place, as well as Philip and Alice's journey through a Europe that's beginning to develop the same syndrome. Like Wenders, Philip takes photographs of urban desolation, but in the end his essential humanism prevails.

Wednesday, April 20, 2016

Wings of Desire (Wim Wenders, 1987)

Angels are usually a tiresome element in movies. I loathe the stickiness of the way they're conceived in movies like It's a Wonderful Life (Frank Capra, 1946), and even actors of the caliber of Cary Grant and Denzel Washington can't do much with playing them in films like The Bishop's Wife (Henry Koster, 1947) and its remake, The Preacher's Wife (Penny Marshall, 1996). Maybe it's because I subscribe to Rilke's dictum, Ein jeder Engel ist schrecklich -- every angel is terrible. Only a filmmaker of genius like Wim Wenders can transcend the essential cheesiness of their presence in a plot -- a cheesiness that lingers in the American remake of Wings of Desire, City of Angels (Brad Silberberg, 1988). The idea that there are angels watching over our lives, reading our thoughts, but unseen except by other angels and sometimes by children, is not a very original one. But what distinguishes the working out of this idea by Wenders and scenarists Peter Handke and Richard Reitlinger is the empathetic approach to them as beings who have been around since Creation, watching the course of humankind and unable to alter it, and occasionally so moved by what they see that they choose to give up immortality and become human. And that these angels have a specific territory to cover, in this case the city of Berlin, a nexus of human cruelty and human suffering. Even so, the concept could easily slip into banality without the blend of humor and melancholy that Wenders brings to it, without performers of the caliber of Bruno Ganz and Otto Sander as the angels Damiel and Cassiel, and without the poetic cinematography of Henri Alekan. It was also an inspired choice to cast Peter Falk as himself, an actor shooting a movie set in the Nazi era who is often stopped on the Berlin streets by people who know him as Columbo, the detective he played on television. It's also a witty touch to have Falk turn out to be an ex-angel, able to sense but not see the presence of Damiel and Cassiel. In many ways, however, the real star of the film is the city of Berlin itself -- although Wenders was prevented from shooting in the eastern sector of the city, he uses the Wall as a kind of correlative to the division between angels and humans. Almost everything works in the film, including the shifts from monochrome (the angels' point of view) to color (the humans'), the shabby little bankrupt circus whose star (Solveig Dommartin) Damiel literally falls for, and the score by Jürgen Knieper. I'm not hip enough to appreciate Nick Cave's songs, but their melancholy eccentricity is an essential part of the texture of the film.

Tuesday, April 19, 2016

E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (Steven Spielberg, 1982)

There are movies you can watch over and over, either to savor something you hadn't particularly noticed before or in delighted anticipation of favorite parts. And then there are movies that you wish you could watch the way you did the first time you saw them, with surprise and exhilaration. I first saw E.T. in the summer of its initial release, with my wife and 8-year-old daughter in a theater in Chestnut Hill, Mass. It was an unspoiled delight, not layered over with the years' accretions of commentary and critique. I can never again see the movie that we saw that afternoon in Chestnut Hill. Watching it last night for the first time in years, I found that the best thing about it is that it brought back faint memories of the initial experience. It hasn't grown in my estimation, but on the other hand it also hasn't diminished very much. Spielberg is one of the great cinematic storytellers, particularly in his ability to narrate without words -- a gift that began to vanish from filmmaking with the arrival of sound almost 90 years ago. The opening of the film, with the scurrying, botanizing aliens and the clumsy, sinister humans who want to spy on them, is a near perfect example of showing instead of telling, and Spielberg's use of that technique is threaded throughout the movie. He also knows how to direct people, even precocious actors like Henry Thomas, Drew Barrymore, and Robert MacNaughton, who are utterly convincing in the way that movie kids rarely were before E.T. and seldom have been since. Yes, there are sequences that don't quite work, like the liberation of the frogs in the science class, and the special effects, such as the kids on the flying bicycles, look antiquated. The appearance of the resuscitated E.T., shrouded in a sheet and with a glowing heart, evoking Christian iconography, is a serious misstep. There are times when the John Williams score verges on overkill. And it undeniably helped set the film industry off in the wrong direction away from making movies for adults and toward crowd-pleasers. But all of that is part of the accretion of time. There is a timeless core to E.T. that helps it secure its place among the great movies.

Monday, April 18, 2016

Ant-Man (Peyton Reed, 2015)

|

| Michael Douglas and Paul Rudd in Ant-Man |

Dr. Hank Pym: Michael Douglas

Hope van Dyne: Evangeline Lilly

Darren Cross/Yellowjacket: Corey Stoll

Paxton: Bobby Canavale

Sam Wilson/Falcon: Anthony Mackie

Director: Peyton Reed

Screenplay: Edgar Wright, Joe Cornish, Adam McKay, Paul Rudd

Based on the comics by Stan Lee, Larry Lieber, Jack Kirby

Cinematography: Russell Carpenter

Production design: Shepherd Frankel

Film editing: Dan Lebenthal, Colby Parker Jr.

Music: Christophe Beck

The main reason to see Ant-Man is Paul Rudd, once again proving that casting is the chief thing Marvel has going for it in its efforts to capture the comic-book movie world. Like Robert Downey Jr. in the various Iron Man and Avengers movies, or Chris Pratt in his leap to superstardom in Guardians of the Galaxy (James Gunn, 2014), Rudd has precisely the right tongue-in-cheekiness to bring off a preposterous role, one that the end credits assure us he will be playing again. Rudd, whose quick wit is known from his talk show appearances, also had a hand in the screenplay, which was begun by Edgar Wright and Joe Cornish and revised and finished by Rudd and Adam McKay. For once, a comic book film is better before the CGI flash-and-dazzle take over -- the concluding portion of the film is a bit of a muddle, considering that most of the performers in the action sequences are ants. Indeed, the most impressive special effects in the movie are not the action sequences but the "youthening" of Michael Douglas, who is first seen as the much younger Hank Pym in 1989, looking much as he did in The War of the Roses (Danny DeVito, 1989), one of the films used by the special effects artists as reference. On the other hand, it has to be said here that Rudd doesn't look much older than he did 21 years ago in Clueless (Amy Heckerling, 1995).

Rififi (Jules Dassin, 1955)

The success of Rififi had a lasting effect on the "caper" or "heist" genre, which is still with us in one form or another, including the Mission: Impossible movies. Dassin's 30-minute sequence depicting the break-in and safe-cracking was hailed as a tour de force. I can't help wondering if Robert Bresson saw Rififi before he made his great 1956 film A Man Escaped, which takes a similar wordless and music-free approach to showing the preparations for Fontaine's prison break. Other than that, of course, nothing could be further from Fontaine's noble efforts to find freedom than the larcenous thuggery of Dassin's jewel thieves. Dassin knows, of course, that audiences respond positively to cleverness and skill, which is virtually all that his quartet of thieves have going for them. Tony (Jean Servais) is a brutal ex-con who beats his former mistress (Marie Sabouret) with a belt; Jo (Carl Möhner) is a swaggering, handsome guy for whom Tony took the rap for an earlier heist because Jo has a wife and child; Mario (Robert Manuel) is an easy-going ne'er-do-well; and César (Dassin under the pseudonym Perlo Vita) is a professional safe-cracker. Dassin manipulates us into thinking of these guys as heroes, if only because the gang led by Pierre Grutter (Marcel Lupovici), who wants to muscle in on their ill-gotten gains, is even worse. In the end, both sides are wiped out, but not before Jo's little boy (Dominique Maurin) is kidnapped and held for ransom. The final sequence of the film is particularly harrowing, especially to contemporary viewers used to mandated seatbelts and conscientious childproofing: A dying Tony drives the 5-year-old boy across Paris in an open convertible as the delighted kid stands on and even clambers over the seats of the speeding car. For all its unpleasantness, Rififi is as memorable as it was influential. It led to countless imitations, usually more light-hearted, including Dassin's own Topkapi (1964). It also revived Dassin's career, which had been at a standstill after he was blacklisted in Hollywood; Rififi's international success was a defiant nose-thumbing directed at HUAC's witch hunts.

Sunday, April 17, 2016

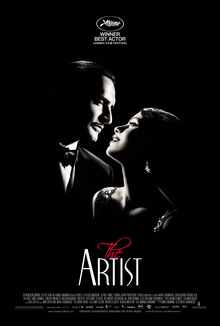

The Artist (Michel Hazanavicius, 2011)

There are two classic movies about the effect of the arrival of sound on films and the people who were silent-movie stars, Singin' in the Rain (Stanley Donen and Gene Kelly, 1952) and Sunset Blvd. (Billy Wilder, 1950). Neither of them won the Academy Award for best picture. Coming half a century later, Michel Hazanavicius's The Artist, which did, looks oddly like an anachronism. It is certainly a tour de force: a mostly silent film with a few witty irruptions of sound in the middle when the protagonist George Valentin (Jean Dujardin), having learned that his career as a film star is ending, suddenly begins to hear sounds, even though he seems incapable of producing them himself. (At the end of the film, Valentin speaks one line, "With pleasure," revealing his French accent.) The project grew out of Hazanavicius's admiration of silent films and their directors, and it fulfilled his own desire to make one himself. The title and the central predicament of George Valentin are an acknowledgement of the fact that silent film is a distinct art form, one lost with the advent of sound. At the expense of his career, Valentin insists on preserving the art -- much as Charles Chaplin did by refusing to make City Lights (1931) and Modern Times (1936) into talkies, long after sound had taken hold. But Valentin is no Chaplin, and his effort, an adventure story in the mode of the films that had made him famous, is a flop, coincidentally opening on the day in 1929 when the stock market crashed. Meanwhile, a younger fan and something of a protégée of his, Peppy Miller (Bérénice Bejo), becomes a huge star in talkies. From this point on, the script almost writes itself, especially if you've seen any of the versions of A Star Is Born, which is why some of us wonder how this undeniably entertaining film became such a hit and a multiple award-winner. It was nominated for 10 Academy awards and won half of them: picture, actor, director, costume design (Mark Bridges), and original score (Ludovic Bource). To my mind, Hazanavicius's screenplay is at fault for not making Valentin's supine reaction to sound entirely credible: Is it actor's ego? A fear of the new? Embarrassment at his accent? And the decision to play Valentin's suicide attempt as comedy feels like a failure of tone on the part of the writer-director. That said, the performances by Dujardin, Bejo, and the always invaluable John Goodman as the studio boss keep the movie alive. I just don't think it belongs in the company of Singin' in the Rain and Sunset Blvd.

Saturday, April 16, 2016

Wild Strawberries (Ingmar Bergman, 1957)

The portrait of old age in Wild Strawberries was created by a writer-director who was 39, which is about the right time for someone to become obsessed with the past and with the portents of dreams. In the film, Isak Borg (Victor Sjöström) is 78, and by that time -- speaking as one who is nearing that age -- most of us have come to terms with the past and made sense of (or perhaps just accepted as a given) the memories and dreams that persist in haunting us. But although Bergman's film, one of the handful of breakthrough films he made in the mid-1950s, may not ring entirely true psychologically, it holds up thematically. Isak Borg is about to be commemorated with an honorary degree, one that stamps him as over the hill, and it's not surprising that it forces him to reflections about the course of his life. He is not about to go gentle into a night that he thinks of as neither good nor bad, but the journey he takes during the film -- this is an Ingmar Bergman "road movie," after all -- helps him decide to accept his life, mistakes and all. The brilliantly crabby performance by Sjöström holds it all together, even though the movie occasionally misfires: The squabbling young hitchhikers Anders (Folke Sundquist) and Viktor (Björn Bjelfenstam), who come to blows over religious faith, could almost be a self-parody of Bergman's own obsession, which would play itself out rather tiresomely in his "trilogy of faith," Through a Glass Darkly (1961), Winter Light (1963), and The Silence (1963). And the dream sequence in which Borg sees his late wife (Gertrud Fridh) and her lover (Åke Fridell) adds little to our understanding of the character. It's also possible to find the reconciliation of Borg's son (Gunnar Björnstrand) and daughter-in-law (Ingrid Thulin) a little too easily achieved, as if thrown in as a correlative to Borg's own affirmation. The radiant performance of Bibi Andersson in the double role of Borg's cousin Sara and the young hitchhiker who shares her name, however, almost brings the film into convincing focus. I don't think Wild Strawberries is a masterpiece, but it's certainly one of the essential films in the Bergman oeuvre.

Friday, April 15, 2016

42nd Street (Lloyd Bacon, 1933)

Julian Marsh: Warner Baxter

Dorothy Brock: Bebe Daniels

Peggy Sawyer: Ruby Keeler

Billy Lawler: Dick Powell

Abner Dillon: Guy Kibbee

Lorraine Fleming: Una Merkel

Ann Lowell: Ginger Rogers

Pat Denning: George Brent

Thomas Barry: Ned Sparks

Director: Lloyd Bacon

Screenplay: Rian James, James Seymour

Based on a novel by Bradford Ropes

Cinematography: Sol Polito

Art direction: Jack Okey

Songs: Al Dubin, Harry Warren

Costume design: Orry-Kelly

Choreography: Busby Berkeley

42nd Street is only mildly naughty, bawdy, or sporty, as the lyrics of Al Dubin and Harry Warren's title song would have it, but once Busby Berkeley takes over to stage the three production numbers at the movie's end, it is certainly gaudy. What naughtiness and bawdiness it contains would not have been there at all once the Production Code went into effect a year or so later. It's doubtful that Ginger Rogers's character would have been called "Anytime Annie" once the censors clamped down, or that anyone would say of her, "She only said 'no' once and then she didn't hear the question." Or that it would be so clear that Dorothy Brock is the mistress of foofy old moneybags Abner Dillon. Or that there would be so many crotch shots of the chorus girls, including the famous tracking shot between their legs in Berkeley's "Young and Healthy" number. Although it's often remembered as a Busby Berkeley musical, it's mostly a Lloyd Bacon movie, and while Bacon is not a name to conjure with these days, he does a splendid job of keeping the non-musical part of the film moving along satisfactorily. It helps that he has a strong lead in Warner Baxter as the tough, self-destructive stage director Julian Marsh, balanced by such skillful wisecrackers as Rogers, Una Merkel, and Ned Sparks. But it's a blessing that this archetypal backstage musical became a prime showcase for Berkeley's talents. Dick Powell's sappy tenor has long been out of fashion, and Ruby Keeler keeps anxiously glancing at her feet while she's dancing, but Berkeley's sleight-of-hand keeps our attention away from their faults. Nor does anyone really care that his famous overhead shots that turn dancers into kaleidoscope patterns would not be visible to an audience in a real theater. In the "42nd Street" number, Berkeley also introduces his characteristic dark side: Amid all the song and dance celebrating the street, we witness a near-rape and a murder. It's a dramatic twist that Berkeley would repeat with even greater effect in his masterpiece, the "Lullaby of Broadway" number from Gold Diggers of 1935. Berkeley's serious side, along with the somewhat downbeat ending showing an exhausted Julian Marsh, alone and ignored amid the hoopla, help remind us that the studio that made 42nd Street, Warner Bros., was also known for social problem movies like I Am a Fugitive From a Chain Gang (Mervyn LeRoy, 1932) and the gangster classics of James Cagney, Humphrey Bogart, and Edward G. Robinson.

Thursday, April 14, 2016

Death in Venice (Luchino Visconti, 1971)

|

| Dirk Bogarde in Death in Venice |

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)