A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Tuesday, September 27, 2016

Heaven's Gate (Michael Cimino, 1980)

Heaven's Gate, for all its history as a calamitous flop, is not so much a bad movie as an inchoate one. You can see it go awry from the very beginning, when it tries to pass off the ornate architecture of Oxford University, where the scenes were filmed, for the spare red brick and granite of Harvard Yard. The film opens with a frenzied commencement for the Harvard class of 1870, which devolves into a swirling dance to the "Blue Danube" waltz. It's potentially an exhilarating opening, but it goes on and on and on, and serves almost no purpose in the rest of the film, except to introduce us to James Averill (Kris Kristofferson) and his friend William C. Irvine (John Hurt), members of the graduating class. Then the film jumps 20 years, to Wyoming, where Averill is marshal of Johnson County. We never learn why Averill, who is a wealthy man, winds up in this hard and thankless job, living in near-squalor and hooked up with Ella Watson (Isabelle Huppert), the madam of a brothel. As for Irvine, with whom Averill reunites during a stopover in Casper on his way back to Johnson County, he has somehow become involved with the Wyoming Stock Growers Association, a group of cattlemen led by the sinister Frank Canton (Sam Waterston) who are trying to keep immigrants from settling on the land they want to graze. It's clear that director-screenwriter Michael Cimino at some point wanted Irvine, who is presented as an effete intellectual, to serve as a kind of chorus, commenting on the action, and as a foil to the more robust Averill, but Irvine keeps getting lost in the turns of the narrative and the excesses of Cimino's ideas. (The shooting took so long that Hurt was able to film David Lynch's The Elephant Man during his down time from Heaven's Gate.) In Casper we also meet Nathan Champion (Christopher Walken), who works as a kind of hit man for the cattlemen. But Champion is also a friend of Averill's and a rival of his for the attentions of Ella. There is the core of a more conventional Western in the relationships among these characters, but Cimino isn't interested in being conventional. What he is interested in are the elaborate set pieces like the waltz scene, a later scene with dozens of couples on roller skates, enormous throngs of extras milling through the streets of Casper, crowds of immigrants making their way to Johnson County, and battle scenes in which the citizens of the Johnson County settlement retaliate against the troops led by Canton that are determined to exterminate them. There are pauses in the hullabaloo for quieter scenes designed to work out the triangle formed by Averill, Champion, and Ella, but their characters are so lightly sketched in that we don't have much sense of the motives behind their sometimes enigmatic actions. And yet, it's a somehow maddeningly watchable film, thanks in large part to the often breathtaking cinematography of Vilmos Zsigmond, a committed performance by Huppert, the Oscar-nominated sets of Tambi Larsen and James L. Berkey, and yes, the sheer extravagance of what Cimino throws onto the screen. Without a plausible screenplay it could never have been a good film, but occasionally you can see how it might have been a great one.

Monday, September 26, 2016

Sicario (Denis Villeneuve, 2015)

|

| Benicio Del Toro and Emily Blunt in Sicario |

Alejandro: Benicio Del Toro

Matt Graver: Josh Brolin

Dave Jennings: Victor Garber

Ted: Jon Bernthal

Reggie Wayne: Daniel Kaluuya

Steve Foring: Jeffrey Donovan

Manuel Diaz: Bernardo Saracino

Silvio: Maximiliano Hernández

Director: Denis Villeneuve

Screenplay: Taylor Sheridan

Cinematography: Roger Deakins

Production design: Patrice Vermette

Film editing: Joe Walker

Music: Jóhann Jóhannson

Sicario is a suspenseful, well-directed, superbly acted, and finely photographed film whose chief flaw is that it can't decide between what it needs to be, an action thriller, and what it wants to be, a biting commentary on the international social and political consequences of the War on Drugs. As the latter, Sicario could almost be a postscript to Traffic (Steven Soderbergh, 2000), to the point that it casts Benicio Del Toro, who won an Oscar for the earlier film, in the key role of Alejandro, a CIA operative with a personal agenda. Emily Blunt, an actress who seems to be able to do anything (she's been cast as Mary Poppins in a forthcoming sequel), plays Kate, a young FBI agent whom we first see leading a SWAT raid on a house in Chandler, Ariz., that is suspected of being a link to a Mexican drug cartel. Not only is the house full of dozens of corpses, an outlying building explodes when agents try to open a locked trap door, killing two of them. Because of her work on the raid, Kate is offered an assignment on a special team to capture Manuel Diaz, the man responsible for the bombing. The operation is headed by Matt Graver, a jokey, casual, swaggering type whom Kate's partner, Reggie, mistrusts immediately. Kate herself gets stonewalled when she tries to get more details about their mission, and even what part of the government Graver and his mysterious, taciturn partner, Alejandro, work for. It's the CIA, of course, and Kate's presence on the mission is largely to provide an excuse for the presence of the agency on this side of the border, where it's not supposed to operate unless it's working with domestic law enforcement. Their first mission, in fact, is across the border, to Juárez, where they are to pick up an associate of Diaz's who has been captured and is being extradited. Much of this trip is seen from the air: We watch the line of SUV's, looking from above like large black beetles, that carry the members of the task force across the border, smoothly gliding around the traffic backed up at the checkpoint and into the city. It's on the return trip that they encounter a bottleneck: a staged traffic accident strands the convoy in traffic, where they are ambushed by cartel operatives trying to prevent the captured man from testifying. Having survived this encounter, Kate is naturally more determined than ever to get some answers to her questions about the real nature of the mission and the exact roles being played by Graver and Alejandro in it, but she will find that the more she knows, the more danger she is in. Intercut with Kate's story are vignettes of the life of Silvio, a Juárez cop, and his wife and young son. Director Denis Villeneuve and screenwriter Taylor Sheridan keep the significance of these scenes from us until they finally merge with the principal plotline toward the end of the film. It does not end well, of course. Kate has a disillusioning revelation about the purpose of the mission that has put her in harm's way several times, and although the downer ending of the film has an impact of its own when it comes to social and political commentary, it clashes oddly with the generic thriller medium in which it's set. But Villeneuve's direction serves both elements of the film well, Roger Deakins's cinematography received a well-deserved Oscar nomination, and Joe Walker's film editing probably deserved one.

Sunday, September 25, 2016

McCabe & Mrs. Miller (Robert Altman, 1971)

|

| Warren Beatty and Julie Christie in McCabe & Mrs. Miller |

Saturday, September 24, 2016

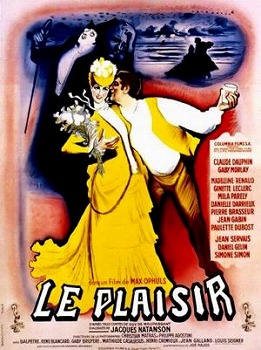

Le Plaisir (Max Ophuls, 1952)

Pleasure, as the poets never tire of telling us, is inextricable from pain. Le Plaisir is an anthology film dramatizing three stories by Guy de Maupassant that center on what has been called the pleasure-pain perplex. An elderly man nearly dances himself to death in an attempt to recapture his youth. The patrons of a brothel quarrel and even come to blows when they discover that it is closed. An artist marries his mistress to atone for his cruelty to her. Max Ophuls brings all of his elegant technique to the stories, including his characteristic restless camera, which prowls around the wonderful sets by Jean d'Eaubonne, who received a well-deserved Oscar nomination for art direction. It's also, like Ophuls's La Ronde (1950), an all-star production -- if your stars are French. Claude Dauphin plays the doctor who treats the youth-seeking dancer; Madeleine Renaud is the madame of the brothel, Danielle Darrieux is one of her "girls," and Jean Gabin plays the madame's brother, who invites her to bring the girls to the country for his daughter's first communion, hence the temporary closure of the brothel; Daniel Gélin is the artist, Simone Simon his model/mistress, and Jean Servais his friend who also narrates the final section. Of the three segments of the film, the middle one is the longest and I think the most successful, moving from the raucous opening scene in which the men of the small Normandy town discover the brothel closed into a comic train ride to the country, which is as fetchingly pastoral a setting as you could wish. The sequence climaxes with the filles de joie dissolving in tears at the first communion -- the little church in which it takes place is one of d'Eaubonne's most inspired sets -- then returning to town and a joyous welcome. Intriguingly, Ophuls never lets us inside the brothel: We see it only as voyeurs, through the windows. Nothing of this segment is "realistic" in the least, making the melancholy first and last segments more important in establishing the film's theme and tone. The first segment does its part to set up the course of the film as a whole, beginning with a riotous opening as tout Paris flocks to the opening of a dance hall, a pleasure palace, followed by scenes of lively dancing, then the collapse of the elderly patron, who is wearing a frozen and rather creepy mask of youth, and concluding with the bleakness of his normal existence, tended by his aging wife, who is fittingly played by Gaby Morlay, once a silent film gamine. The final segment is the bleakest of all, as the film concludes with the artist pushing his wheelchair-bound wife along the seashore, penance for having provoked her suicide attempt. The film leaves me with something like the feeling I get from the song "Plaisir D'Amour."

Plaisir d'amour ne dure qu'un moment.

Chagrin d'amour dure toute la vie.

The pleasure of love lasts only a moment. The pain of love lasts a lifetime.

Plaisir d'amour ne dure qu'un moment.

Chagrin d'amour dure toute la vie.

The pleasure of love lasts only a moment. The pain of love lasts a lifetime.

Friday, September 23, 2016

Shane (George Stevens, 1953)

I had forgotten how important the sexual tension between Shane (Alan Ladd) and Marian Starrett (Jean Arthur) is to the texture and motivation of the film. It's obvious from the moment when she watches him, shirtless and glistening with sweat, help her rather dull (and fully clad) husband, Joe (Van Helflin), uproot a tree stump, and it plays like a low bass note throughout the film, until it becomes the main reason why Shane feels he has to move on at the end. After all, he has just humiliated Joe by knocking him unconscious and taking on the role Joe assumes is his rightful duty, thereby reducing him in the eyes of his wife and son, Joey (Brandon De Wilde). It also doesn't escape the notice of the bad guys, one of whom taunts Shane with the fact that Joe has a pretty wife. (The filters used on some of Arthur's closeups are a giveaway: She was 50 when she made Shane, her last film, but she's plausible as a character 10 or 15 years younger.) It's to George Stevens's credit that he plays all of this as low-key as he does. It would have been much too easy to move the eternal triangle to the center of the film's structure. Shane is an intelligent film, though to my mind it gets a little heavy-handed with the introduction of the black-hatted Wilson (Jack Palance) as the potential nemesis to the knight errant Shane. As fine as Palance's performance is, I wish his character had been given a more complex backstory than just "hired gun out of Cheyenne." Otherwise, the screenplay by A.B. Guthrie Jr. does a fair job of not making its villains too deep-dyed: The chief tormenter of the sodbusters, the cattleman Rufus Ryker (Emile Meyer), is given a speech justifying himself as having gotten there first and settled the land -- we haven't yet reached the point in historical consciousness where the claims of the Native Americans are taken seriously. And Shane's first opponent, Chris Calloway (Ben Johnson), eventually has a change of heart -- not an entirely convincing one to my mind, considering Calloway's behavior in his first encounter with Shane -- and warns Shane that Joe's appointment with Ryker is a trap. Stevens uses Jackson Hole, Wyoming, almost as effectively as John Ford used Monument Valley, and Loyal Griggs won a well-deserved Oscar for his cinematography, even if Paramount's decision to trim the original images at top and bottom to make the film appear to have been shot in a widescreen process resulted in some oddly cropped compositions. Shane is undeniably a classic, but I think it takes itself a little too seriously: The great Western directors, like Ford and Howard Hawks, knew the value of a little comic relief, but in Shane even Edgar Buchanan plays it straight.

Thursday, September 22, 2016

Mean Girls (Mark Waters, 2004)

|

| Rachel McAdams and Lindsay Lohan in Mean Girls |

Wednesday, September 21, 2016

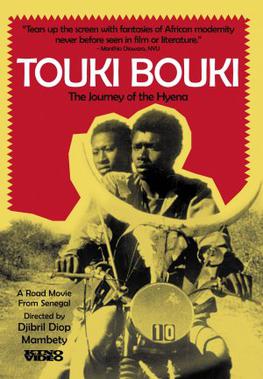

Touki Bouki (Djibril Diop Mambéty, 1973)

Djibril Diop Mambéty once reinterpreted the old cliché about the relationship between movies and dreams by saying, "Cinema is magic in the service of dreams." Touki Bouki is certainly dreamlike, with its jump cuts and flashbacks, its almost hallucinatory saturated colors -- the recently restored version makes the most of Georges Bracher's cinematography -- and its scenes that challenge us to decide whether they represent reality or the characters' fantasies. It was made "the way I dream," Mambéty said. It begins with a nightmare shock: We see a herd of long-horned cattle, filmed with a long lens, approaching us, being guided by a young boy -- a literally bucolic moment. But suddenly the film cuts to a scene of a cow being forced to enter a slaughterhouse, and soon we are inside the abattoir, watching as cattle are being killed, our eyes assaulted by the vivid red of the spurting blood and the filthy, blood-soaked killing floor. It's a horrifying moment, but a real one, and the film, I think, never quite recovers from it. Then we meet the protagonist, a young man called Mory (Magaye Niang). who rides a motorbike with a cow's skull affixed to its handlebars. Mory and his girlfriend, Anta (Mareme Niang), have dreams of escaping their life in the slums on the fringes of Dakar, Senegal, and starting a new one in Paris. On the soundtrack we hear Josephine Baker's song "Paris, Paris, Paris," which becomes a motif in the film, just as later the French soprano Mado Robin's recording of a song about lost love, "Plaisir d'Amour," also recurs. The film then follows Mory and Anta as they explore various ways of getting the money for their trip, some of which are more fantastic than others. When they finally board the ship, however, Mory has a change of heart and runs away, leaving Anta to make the journey on her own. The basic narrative, then, is about the postcolonial dissonance of cultures, and the film is loaded with symbolic motifs like the slaughtered cattle and the skull on Mory's motorbike -- he finds the skull shattered and the bike ruined at the end. But Mambéty's use of the dreamlike elements of montage and camerawork lifts the film above any simplistic symbolic or allegorical treatment of the theme. There are moments in the film that defy literal-minded interpretation: The movie becomes a dream about dreamers.

Tuesday, September 20, 2016

Accattone (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1961)

|

| Franco Citti in Accattone |

Stella: Franca Pasut

Maddalena: Silvana Corsini

Ascenza: Paola Guidi

Amore: Adriana Asti

Director: Pier Paolo Pasolini

Screenplay: Pier Paolo Pasolini, Sergio Citti

Cinematography: Tonino Delli Colli

Film editing: Nino Baragli

There are times in Pasolini's first feature when he seems to be trying out things that he will accomplish with greater finesse in his later films. For example, there are several walk-and-talk tracking shots in which Accattone and another person walk down a street toward a receding camera. This technique was used with greater force and wit in Pasolini's next film, Mamma Roma (1962), in which Anna Magnani strides down a nighttime street, talking about her life, as various people emerge from the darkness to deliver comments on what she is telling us. We've seen this sort of thing done many times since the development of the Steadicam -- it has become a kind of cliché in films and TV shows written by Aaron Sorkin -- but even though the shadow of the retreating camera rig occasionally creeps into the frame in Accattone, Pasolini and cinematographer Tonino Delli Colli execute it with considerable skill. Skill is not always in evidence in Accattone, which has its rough, raw edges. It's not always easy to follow Pasolini's screenplay, drawn in part from his early novels, when it comes to the relationships between the various characters: I'm not clear, for example, who the young woman with several small children is who shares a room with Maddalena and later Stella. Pasolini had worked with Federico Fellini on Nights of Cabiria (1957) and it's instructive to compare the two films: Fellini's has greater technical finish, but it's also less harsh and more sentimental, which may be why Fellini, who originally planned to produce Pasolini's film, withdrew his support. But the rawness of Accattone is entirely appropriate for a film that evokes the spontaneity and actuality of early Italian Neo-Realism with its non-professional actors and ungroomed settings. And it has at its center a charismatic performance by Citti, an untrained actor who went on to a long career on-screen that included an appearance as Calo, one of Michael Corleone's Sicilian bodyguards in The Godfather (Frances Ford Coppola, 1972). "Accattone" is a nickname that means "beggar" or "ne'er-do-well" or "layabout" -- the character's given name is Vittorio Cataldi -- and is entirely appropriate for a character who begins as a pimp and, after hitting the skids and even trying work (at which he shudders), winds up as a thief -- a dead thief. Citti's voice was dubbed in the film, but most of the work is done by his extraordinarily expressive face and by a physical commitment to the role. There is, for example, a terrific fight scene between Accattone and the men of his ex-wife's family, which ends with Accattone and his opponent locked together in a struggle in the dirt, neither willing to relinquish hold. Pasolini also emphasizes the dissonance between a world that produces an Accattone and the religious background from which it springs by using excerpts from Bach's St. Matthew Passion on the soundtrack.

Monday, September 19, 2016

Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (Stanley Kubrick, 1964)

In 1964, Stanley Kubrick told us that the world would end not with a whimper but a "Yeehaaa!" And given the bullying and posturing jingoism currently on display in the American presidential campaign, he may have been right. A lot of Dr. Strangelove has dated: There is no Soviet Union anymore, and the arms race has gone underground (where it may be more dangerous than ever). Some of the gags in the script by Kubrick, Peter George, and Terry Southern have gone stale, such as the jokey character names: Jack D. Ripper, "Bat" Guano, Merkin Muffley. (Although to fault Dr. Strangelove for that is as pointless as faulting Ben Jonson for naming characters in The Alchemist Sir Epicure Mammon and Doll Common. Satire loves its labels.) Where Dr. Strangelove has not dated, however, is in its attitude toward power and those who love and seek it to the point where it becomes an end in itself. Those in Kubrick's film who are capable of seeing the larger picture are ineffectual, like President Muffley (Peter Sellers) and Group Capt. Mandrake (Sellers). They are invariably steamrollered by those in pursuit of the immediate goal, like Gen. Ripper (Sterling Hayden) defending his precious bodily fluids, or Gen. Turgidson (George C. Scott) devoting himself to getting the upper hand on the Russkies, even to the extent of getting our hair mussed a little, or Dr. Strangelove (Sellers) himself, enraptured by the wonders of military technology. But the film really works by Kubrick's mastery of his medium: We find ourselves, against our better judgment, rooting for the bomber crew to reach its target, thanks to the way Kubrick, with the help of film editor Anthony Harvey, manipulates our love of war movie clichés. The film is full of classic over-the-top performances, especially from Hayden and Scott, and of course Sellers's Strangelove is a touchstone mad scientist character, anticipating Edward Teller's selling Ronald Reagan on "star wars" by a couple of decades. In fact, if the film seems to us have dated, it may be that reality has outstripped satire. Who could have invented Donald Trump?

Sunday, September 18, 2016

Les Enfants Terribles (Jean-Pierre Melville, 1950)

Les Enfants Terribles was released in the United States as The Strange Ones, which has the effect of reducing monstrosity to mere nonconformity. For the siblings Elisabeth (Nicole Stéphane) and Paul (Édouard Dermithe) are monsters, even if they are perhaps more destructive to each other than they are to other people. Not that Jean Cocteau, who adapted the screenplay from his own novel, had anything against monsters: He created the most memorable non-animated version of Beauty and the Beast (1946), after all. Les Enfants Terribles was an uneasy collaboration between Cocteau and director Jean-Pierre Melville; being no slouch as a director himself, Cocteau was capable of imposing his ideas on Melville, who was almost 30 years younger. But somehow they prevailed and produced a film that is either a "masterpiece," as David Thomson calls it, or "pretentious poppycock," as Bosley Crowther, the New York Times critic, called it. I trust Thomson's judgments far more than those of Crowther, a notorious fuddy-duddy, but I prefer to think of the film as not "either/or" but instead "both/and." It's certainly not poppycock in any case, especially in its depiction of adolescence as a kind of fever dream, and the way incest flickers around the relationship of Paul and Elisabeth like heat lightning. But there is certainly a whiff of pretentiousness in the voiceover narration (by Cocteau himself) that hammers home the folie à deux of the siblings, which is apparent without any comment. If it's a masterpiece, which I'm not entirely confident in calling it, it becomes one from Melville's staging, in collaboration with production designer Emile Mathys, Henri Decaë's cinematography, and especially the performance of Stéphane, whose invocation of Lady Macbeth in one scene makes me wish she had played the part on film. Melville didn't want to cast Dermithe, Cocteau's lover, in the role of Paul, and I think he was right. At 25, Dermithe was too old and too sturdy to play the neurasthenic 16-year-old who is felled by a snowball. But Renée Cosima is impressive in the dual role of Dargelos, the schoolboy who throws the snowball, and Agathe, who falls into Elisabeth's clutches as a weapon with which to torment her brother.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)