A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Tuesday, October 18, 2016

Madame de... (Max Ophuls, 1953)

The word "tone" is much bandied about by critics, myself included. We speak of a film as being "inconsistent in tone" or its "melancholy, despairing tone" or its "shifts in tone." But ask us -- or, anyway, me -- what we mean by the term, and you may get a lot of stammering and hesitation. Even my old copy of the Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics falls back on calling it "an intangible quality ... like a mood in a human being." So when I say that Madame de... is a masterwork in its manipulation of tone, you have to take that observation as a kind of awestruck, slightly inarticulate response to a film that begins in farce and ends in tragedy. The American title of the film was The Earrings of Madame de..., but to my mind that puts the emphasis on what is, in effect, merely a MacGuffin. The earrings were given to Countess Louise de... (Danielle Darrieux) by her husband, General André de... (Charles Boyer), on their wedding day. (Their full surname is coyly hidden throughout the film: A sound blots out the latter part of the name when it is spoken, and it is hidden by a flower when it appears on a place card at a banquet. The effect is rather like a newspaper gossip column trying to avoid a libel suit when reporting a scandal among the aristocracy.) The scandal is set in motion when Louise, a flirtatious woman with many admirers, decides to sell the earrings to pay off the debts she wants to hide from André. Their marriage has obviously come to a pause: Though they remain affectionate with each other, they have separate bedrooms and at night they talk to each other through doors that open on a connecting room. Louise takes the earrings to the jeweler (Jean Debucourt) from whom André originally purchased them. But when she tries to persuade André that she lost them at the opera and the "theft" is reported in the newspapers, the jeweler tries to sell them back to the general. To put an end to the business, André pays for them, then presents them to his mistress, Lola (Lia Di Leo), as a parting gift: Their affair over, she is leaving for Constantinople. There, Lola gambles them away, but they are bought by an Italian diplomat, Baron Donati (Vittorio De Sica), who is on his way to a posting in Paris. And of course Donati meets Louise, they fall in love, and he presents the earrings to her as a gift. Recognizing them, she has no recourse but to hide them, but they will resurface with fatal results. How Max Ophuls gradually shades this plot from a situation suited to a Feydeau farce into a poignant conclusion is a part of the film's magic. It depends to a great extent on the superb performances of Darrieux, Boyer, and De Sica, but also on Ophuls's typically restless camera, handled -- as in Ophuls's La Ronde (1950), Le Plaisir (1952), and Lola Montès (1955) -- by cinematographer Christian Matras, as it explores Jean d'Eaubonne's elegant fin de siècle sets. Much depends, too, on the film editor, Borys Lewin, who helps Ophuls accomplish one of the movies' great tours de force, following Louise and Donati as they dance what appears to be an extended waltz but gradually shows itself to be several waltzes taking place over the period of time in which they fall in love. It's a cinematic showpiece, but it's fully integrated into what has to be one of the great movies.

Monday, October 17, 2016

Dukhtar (Afia Nathaniel, 2014)

Sunday, October 16, 2016

Easy Living (Mitchell Leisen, 1937)

Easy Living is one of my favorite screwball comedies, but I once had a nightmare that took place in the set designed by Hans Dreier and Ernst Fegté for the film. It was the luxury suite in the Hotel Louis, with its amazingly improbable bathtub/fountain, and I dreamed that we had just bought a place that looked like it and were moving in. I don't remember much else, other than that I was terribly anxious about how we were going to pay for it. Most of my dreams are anxiety dreams, I think, which may be why I love screwball comedies so much: They take our anxieties about money and love and work, like Mary Smith (Jean Arthur) worrying about how she's going to pay the rent and even eat now that she's lost her job, and transform them into dilemmas with comic resolutions. Too bad life isn't like that, we say, but with maybe a kind of glimmer of hope that it will turn out that way after all. Easy Living, with its screenplay by Preston Sturges, is one of the funniest screwball comedies, but it's also, under Mitchell Leisen's direction, one of the most hilarious slapstick comedies. How can you not love a film in which a Wall Street fat cat (Edward Arnold) falls downstairs? Or the celebrated scene in which the little doors in the Automat go haywire, producing food-fight chaos that builds and builds? The fall of the fat cat and the rush on the Automat reveal that Easy Living was a product of the Depression, anxiety made pervasive and world-wide, when we needed hope in the form of comic nonsense to keep us going. This is also an essential film for those of us who love Preston Sturges's movies, for although he didn't direct it, his hand is evident throughout, not only in the dialogue but also in the casting, with character actors who would later form part of Sturges's stock company, Franklin Pangborn, William Demarest, and Robert Greig among them. Ray Milland displays a Cary Grant-like glint of amusement at what's going on, Luis Alberni spouts Sturges's wonderful malapropisms as the hotel owner Louis Louis, and Mary Nash brings the right amount of indignation and humor to her role as Arnold's wife. I only wonder why Ralph Rainger and Leo Robin weren't credited for their title song, which is heard (though without its lyrics), as background music throughout the film.

Saturday, October 15, 2016

Fugitive Pieces (Jeremy Podeswa, 2007)

I dislike the phrase "Holocaust film," which often gets used with a hint of condescension, suggesting that there is a genre of film that plays on our established feelings of grief and indignation about a terrible passage in history. It seems to imply that filmmakers who tell stories about the Holocaust and its effects are working with a subject that disarms criticism: that if it's about the Holocaust, a film doesn't have to worry about winning over an audience. That attitude ignores, for example, the controversy that surrounded Roberto Benigni's Life Is Beautiful (1997), which was both celebrated and condemned. The enormity of the Holocaust tends to overwhelm conventional cinematic narrative, so that the best films in which it forms the background are those that focus on the experiences of actual people like Oskar Schindler in Schindler's List (Steven Spielberg, 1993) and Wladyslaw Szpilman in The Pianist (Roman Polanski, 2002), or thinly fictionalized accounts drawn from personal experience, like Louis Malle's in Au Revoir les Enfants (1987). Jeremy Podeswa's Fugitive Pieces, adapted by the director from a novel by Anne Michaels, is one of those films that are almost swamped by the historical actuality of the Holocaust; it takes as its subject the experience of "survivor guilt." Its fictional protagonist, Jakob Beer (played as a child by Robbie Kay and as a man by Stephen Dillane), escapes from the Nazis but loses his family. He is rescued by Athos Roussos (Rade Serbedzija), a Greek archaeologist who was working in Poland on a dig and discovered Jakob hiding in the woods. Somehow -- the film is unclear on exactly how -- Athos smuggles Jakob out of Poland to his home in Greece, and after the war the two emigrate to Canada, where Athos has been invited to teach. Jakob grows up haunted by his childhood trauma, and his first marriage, to a woman named Alex (Rosamund Pike), ends when she reads his journals and discovers what a barrier Jakob's experiences have created between them. Jakob is particularly tormented by the loss of his sister, Bella (Nina Dobrev), a talented musician, who often appears in his dreams. Even after publishing a book about his life, Jakob doesn't fully overcome the past until after the death of Athos, whose wisdom he comes to appreciate with the help of another woman, Michaela (Ayelet Zurer). There is a subplot involving the Jewish couple across the hall from Athos and Jakob in Canada, whose son, Ben (Ed Stoppard), grows up hating his father, a Holocaust survivor, for his harshness: The father, for example, berates Ben for not finishing the apple he has been eating, reminding him how grateful people in the camps would have been for the food. Despite excellent performances from everyone, the film sinks too often into sentimentality and stereotypes: Serbedzija's performance is a standout, but he can't overcome the fact that Athos, though a university professor, is presented as too much the wise and kindly peasant-sage, preaching the value of ties to the earth. There are some major gaps in the narrative, like the journey from Poland to Greece, and some overall shapelessness, and the ending is much too pat.

Thursday, October 13, 2016

Bride of Frankenstein (James Whale, 1935)

Funny, campy, occasionally scary, and featuring over-the-top performances by Ernest Thesiger, Dwight Frye, and Una O'Connor, Bride of Frankenstein may also be the saddest of all horror movies. Much has been made of a perceived subtext of the film, based in part on the knowledge that its director, James Whale, and Thesiger were openly gay, and it's possible to see the plight of the monster (Boris Karloff) as analogous to that of the gays of their time, subject to ridicule and repression from a hostile society. In this reading, Whale and Thesiger adopt camp attitudes as a way of thumbing their noses at a hostile, uncomprehending society. But that's an unnecessarily reductive interpretation. The monster is the ultimate outsider, an anomalous and inarticulate being, whatever his sexuality. He briefly finds companionship in the blind hermit (O.P. Heggie) who begins to teach him to speak -- including the word "friend" -- but their relationship is doomed by the intrusion of the world of ordinary humans, a world he can never be part of. In the end, when the mate (Elsa Lanchester) who has been created for him rejects him, his only recourse is self-destruction. "We belong dead!" the monster proclaims. To see Bride of Frankenstein as some sort of parable about gays in society would then be an endorsement of suicide as the only option. Subtexts often reside only in the mind of the beholder, and Whale was too much of an artist to turn his film into any kind of message, however latent in the fantastic tale he is telling. Better instead to relish Karloff's ability to give a subtle performance that shows through pounds of makeup. Or Lanchester's remarkable control and timing in bringing the bride to life, including the squawks and hisses that she claimed to have developed by watching swans in the park. Or John J. Mescall's classic black-and-white cinematography, Charles D. Hall's set designs, and Franz Waxman's score. Yes, Colin Clive and Valerie Hobson are a most improbable couple as the Frankensteins. Clive was far gone into alcoholism and looks it, but nobody could have delivered the line "She's alive! Alive!" more memorably.

Wednesday, October 12, 2016

Au Revoir les Enfants (Louis Malle, 1987)

|

| Raphael Fejtö and Gaspard Manesse in Au Revoir les Enfants |

Tuesday, October 11, 2016

Brooklyn (John Crowley, 2015)

This story about an Irish girl's coming of age has the strong whiff of traditional movie storytelling about it. And that's what makes it so entirely satisfying: It fulfills the need we often feel to be reassured about the stability of familiar things. But it also serves to support its theme, which is that nostalgia can be a trap, or to put it in a phrase that has become a cliché: You can't go home again. Eilis Lacey (Saoirse Ronan) feels stifled in her small Irish town, overshadowed by her pretty and accomplished sister, Rose (Fiona Glascott), and bullied by her vicious, hypocritical employer, Miss Kelly (Brid Brennan), so she decides to go to America. Helped by her church, she gets a room in a Brooklyn boarding house and a job in a department store, gradually loses her shyness and reserve, and falls in love with a sweet-natured young Italian American, Tony Fiorello (Emory Cohen). But when Rose dies suddenly, Eilis returns to Enniscorthy to see her mother and stays long enough to be courted by a young man, Jim Farrell (Domhnall Gleeson), and to begin to see the town in a very different light. The time approaches when she is scheduled to return to America, and she finds herself torn between not just Tony and Jim, but also the small but familiar comforts of the town and a promising but uncertain future in America. She also has a secret that she hasn't shared with anyone, but which the vicious Miss Kelly learns through the Irish-American grapevine. That this dilemma should play itself out with such freshness is a tribute to John Crowley's direction and Nick Hornby's adaptation of Colm Tóibín's novel, but also in very large part to a brilliant performance by Ronan. It's the kind of understated acting that sometimes gets overlooked among performances that chew the scenery with more fervor, but it earned Ronan a well-deserved Oscar nomination. It has to be said that she is supported by splendid performances by Cohen and Gleeson, with Ronan demonstrating a different kind of rapport with each actor. A quiet triumph, but a triumph nevertheless.

Monday, October 10, 2016

Anna Karenina (Joe Wright, 2012)

|

| Jude Law and Keira Knightley in Anna Karenina |

Alexei Karenin: Jude Law

Count Vronsky: Aaron Taylor-Johnson

Stiva Oblonsky: Matthew Macfadyen

Dolly Oblonskaya: Kelly MacDonald

Kitty Scherbatsakaya: Alicia Vikander

Konstantin Levin: Domhnall Gleeson

Countess Vronskaya: Olivia Williams

Princess Betsy: Ruth Wilson

Director: Joe Wright

Screenplay: Tom Stoppard

Based on a novel by Leo Tolstoy

Cinematography: Seamus McGarvey

Production design: Sarah Greenwood

Costume design: Jacqueline Durran

Anyone who wants to shake up an established film genre gets my support, even when what they do doesn't quite work. So I'm okay with what Joe Wright tries to do to the historical costume drama and the adaptation of a famous novel in his version of Anna Karenina. Which isn't to say that I think it works. What does work is the attempt by Wright and his screenwriter, Tom Stoppard, to redress the imbalance I've noted in my entries on two previous film adaptations of Tolstoy's novel, the ones directed by Clarence Brown in 1935 and Julien Duvivier in 1948: the neglect of the half of the novel that deals with Konstantin Levin. Domhnall Gleeson, the Levin of Wright's film, is hardly the Levin Tolstoy describes as "strongly built, broad-shouldered," but Gleeson seems to know what the character is about. And he's beautifully matched with Alicia Vikander, who gives another knockout performance as Kitty. Wright and Stoppard use their story as an effective foil for the obsessive, careless love of Anna and Vronsky. That it's only part of Levin's function in Tolstoy's novel, which gives us a view of Russian reform politics and social structure through Levin's eyes, just goes to show that you can't have everything when you're trying to adapt literature to a medium it isn't quite suited for. Wright has also cast brilliantly. As Karenin, Jude Law elicits sympathy for a character that can easily be reduced to a stock villain, as when Basil Rathbone played him in 1935. I also liked Matthew Macfadyen as Oblonsky, Anna's womanizing brother, and it's fun to see Macfadyen and Knightley together in completely different roles from Mr. Darcy and Elizabeth Bennet, whom they played in Wright's 2005 adaptation of Pride and Prejudice. As Anna, Knightley sometimes looks a bit too much like a gaunt fashion model in the Oscar-winning costumes by Jacqueline Durran, and Taylor-Johnson lays on the preening a bit too much in his bedroom-eyed Vronsky, but they have real chemistry together. Seamus McGarvey's Oscar-nominated cinematography makes the most of Sarah Greenwood's production design. But the decision to film the story partly as as if it were being staged in some impossible, dreamlike theater, but also partly realistically, goes astray. It begins as if it were a comedy, with the philandering Oblonsky sneaking around from his wife both onstage and backstage. And throughout the film, reversions from realistic settings to the theater keep jarring the overall tone. There are occasionally some spectacular uses of the set, as when the horses in Vronsky's race run across a proscenium stage, and in his accident, horse and rider plunge off the stage. Here and elsewhere, Greenwood's design is extraordinarily ingenious. But the theater trope -- all the world's a stage? -- never resolves itself into anything thematically satisfying.

Sunday, October 9, 2016

Anna Karenina (Julien Duvivier, 1948)

|

| Vivien Leigh and Ralph Richardson in Anna Karenina |

Karenin: Ralph Richardson

Vronsky: Kieron Moore

Kitty: Sally Ann Howes

Levin: Niall MacGinnis

Princess Betsy: Martita Hunt

Countess Vronsky: Helen Haye

Sergei: Patrick Skipwith

Director: Julien Duvivier

Screenplay: Jean Anouilh, Guy Morgan, Julien Duvivier

Based on a novel by Leo Tolstoy

Cinematography: Henri Alekan

Costume design: Cecil Beaton

If Greta Garbo is the best reason for seeing Clarence Brown's 1935 version of Anna Karenina, then Ralph Richardson is the best argument for watching this one. As Karenin, Richardson demonstrates an understanding of the character that Basil Rathbone failed to display in the earlier version. In a performance barely distinguished from his usual haughty villain roles, Rathbone played Karenin as a cuckold with a cold heart. Richardson wants us to see what Tolstoy found in Karenin: the wounded pride, the inability to stoop to tenderness that has been bred in him by long contact with Russian society and political status-seeking. Unfortunately, Richardson's role exists in a rather dull adaptation of the novel, directed by Julien Duvivier from a screenplay he wrote with Jean Anouilh and Guy Morgan. Although Vivien Leigh was certainly a tantalizing choice for the title role, she makes a fragile Anna -- no surprise, as she was recovering from tuberculosis, a miscarriage, and a bout with depression that seems to have begun her descent into bipolar disorder. At times, especially in the 19th-century gowns designed by Cecil Beaton, she evokes a little of the wit and backbone of Scarlett O'Hara, but she has no chemistry with her Vronsky, the otherwise unremembered Irish actor Kieron Moore. It's not surprising that producer Alexander Korda gave Moore third billing, promoting Richardson above him. The production, too, is rather drab, especially when compared to the opulence that MGM could provide in its 1935 heyday. There's a toy train early in the film that the special effects people try to pass off as full-size by hiding it behind an obviously artificial snowstorm. As usual, this Anna Karenina is all about building up to Anna's famous demise, this time by taking us into her foreboding nightmare about a railroad worker she saw at the beginning of her affair with Vronsky. And also as usual, the half of the novel dealing with Levin, Tolstoy's stand-in character, is scuttled. In this version, Levin is a balding middle-aged man whose only function is to be rejected by Kitty, who is then thrown over for Anna by Vronsky. There's a perfunctory scene that gives a happy ending to the Levin-Kitty story, but it adds nothing but length to the film. Some of the scenes featuring the supporting cast, especially those with Martita Hunt as Princess Betsy, bring the film to flickering life, but there aren't enough of them to overcome the general dullness.

Saturday, October 8, 2016

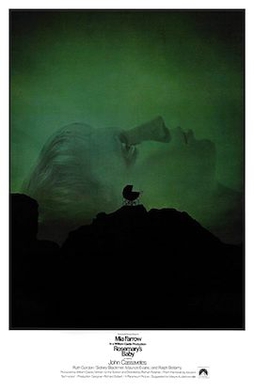

Rosemary's Baby (Roman Polanski, 1968)

I'm not boasting when I say that horror movies don't scare me. Sometimes I wish they did -- I'm missing out on the fun. It's just that since I learned to watch films analytically, studying performance and camerawork and storytelling, I usually see through the formulas of genre films. I know, for example, how to anticipate the surprises when you think that everything's okay and suddenly it isn't anymore -- e.g., the shocker moments in Wait Until Dark (Terence Young, 1967) or Carrie (Brian De Palma, 1976). The best I can hope for from a scary movie is to feel unsettled, which is what Rosemary's Baby does to me. I've seen it often enough to know where it's going, but when it arrives -- especially in the conception scene and in the final reveal -- I invariably suspend my analysis long enough to be drawn in. As director and screenwriter, Roman Polanski is a master, providing lovely, creepy bits like the figures that tiptoe across the background in the scene in which Rosemary (Mia Farrow) thinks she's alone in the apartment. But to my mind the film succeeds mostly because of Farrow's performance: She brings just the right amount of vulnerability to the role -- she doesn't even need the makeup-induced pallor to convince us that she is prey to something terrible. It always strikes me as odd that she has never earned an Oscar nomination. But all the performances in Rosemary's Baby are top-notch, starting with the one that did win an Oscar, Ruth Gordon's deliciously vulgar Minnie Castevet, who pronounces "pregnant" as if it had three syllables. John Cassavetes succeeds in the difficult role of Guy, Rosemary's husband; he has to be plausible as the sympathetic, loving spouse at the start -- giving in to Rosemary's desire for the fatal apartment -- but just abrasive enough with his wisecracks to suggest the cynicism and careerism that leads him to sell his soul to the devil-worshipers. Ralph Bellamy also has to be plausibly caring as Dr. Sapirstein to convince Rosemary and the audience that he's on the right side, while also preparing us for later revelations. Bellamy had a long and interesting career, from the schnook who gets the girl taken away from him by Cary Grant in The Awful Truth (Leo McCarey, 1937) and His Girl Friday (Howard Hawks, 1941), to the distinguished, gentlemanly, but sometimes sinister character in films like Trading Places (John Landis, 1983) and Pretty Woman (Garry Marshall, 1990). It's also good to see other veteran actors -- Sidney Blackmer, Elisha Cook Jr., and even that well-cured ham Maurice Evans -- doing fine ensemble work. Richard Sylbert's production design makes the most of the spooky gothic apartment house -- the exteriors are of the Dakota, but the interiors are sets. And Krzysztof Komeda, who had worked with Polanski in Poland, provides a score that's atmospheric without being overstated -- until it needs to be.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)