A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Tuesday, October 25, 2016

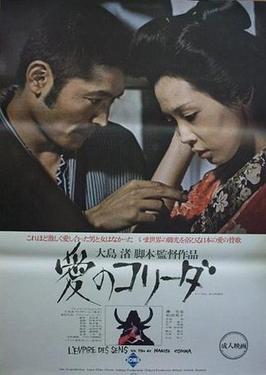

In the Realm of the Senses (Nagisa Oshima, 1976)

Even 40 years later, In the Realm of the Senses still has the power to shock, and not just because of the full nudity and unsimulated copulation -- we've all seen pornography in some form. It's that we've never seen them used in service of story, characterization, and theme as well as they are in this film. It's based on an actual incident that took place in Japan in 1936: Sada Abe killed her lover, Kichizo Ishida, during an experiment in erotic asphyxiation, then cut off his genitals and carried them with her for three days until she was arrested. Fascinated by this story, and by producer Anatole Dauman's suggestion that they should make a pornographic film, Oshima wrote the screenplay and set about putting together a cast and crew. The lead actors, Tatsuya Fuji as Kichizo and Eiko Matsuda as Sada, are extraordinary, transcending the mere shock value of their physical encounters with their commitment to illuminating the motives and the inner life of the couple. They give as complete a portrait of sexual obsession as we're ever likely to encounter in a movie. Oshima doesn't skimp on portraying the excesses of their passion: Sada persuades Kichizo to have sex with the 68-year-old geisha who comes to serenade them -- he is somewhat disgusted, but she is aroused when he does. The maids who tend to their room complain that it smells -- "We like it that way," Sada replies -- and the older man with whom Sada has been having sex to get money to support the lovers ends their relationship by saying she smells somewhat like a dead rat. But Oshima also portrays them as symbolic rebels against the militarism of 1930s Japan -- making love not war, if you will -- in a scene in which Kichizo, returning to Sada, passes marching troops being cheered by flag-waving schoolchildren. The real Sada was tried for his murder and mutilation, but served only five years in prison and became something of a folk legend in Japan, living on until the 1970s. A French and Japanese co-production, In the Realm of the Senses was filmed in Japan, but the footage had to be developed in France to avoid prosecution, and it has never been released in Japan without cuts or strategic blurring of its sex scenes. The movie is often quite beautiful, with cinematography by Hideo Ito and sets by Shigemasa Toda, but it's certainly not a film for all viewers.

Monday, October 24, 2016

My Man Godfrey (Gregory La Cava, 1936)

I don't know if director Gregory La Cava and screenwriters Morrie Ryskind and Eric Hatch intentionally set out to subvert the paradigm of the romantic screwball comedy in My Man Godfrey, but they did. It has all the familiar elements of the genre: the "meet-cute," the fallings-in and fallings-out, and the eventual happily-ever-after ending. And it is certainly one of the funniest members of the genre. William Powell is his usual suave and sophisticated self, and nobody except Lucille Ball ever played the beautiful nitwit better than Carole Lombard. But are Godfrey (Powell) and Irene (Lombard) really made for each other? Isn't there something really amiss at the ending, when Irene all but railroads Godfrey into marriage? Knowing that marriage is an inevitability in the genre, I kept wanting Godfrey to pair off with Molly (Jean Dixon), the wisecracking housemaid who conceals her love for him. And even Cornelia (Gail Patrick), the shrew Godfrey has tamed, seems like a better fit in the long run than Irene, with her fake faints and tears. The film gives us no hint that Irene has grown up enough to deserve Godfrey. Or is that asking too much of a film obviously derived from the formula? Perhaps it's just better to take it for what it is, and to enjoy the wonderful performances by Alice Brady, Eugene Pallette, Alan Mowbray, and Mischa Auer, and the always-welcome Franklin Pangborn doing his usual fussy, exasperated bit. A lot could be written, and probably has been, about how the film reflects the slow emergence from the Depression, with its scavenger-hunting socialites looking for a "forgotten man." a figure that only three years earlier, in Gold Diggers of 1933 (Mervyn LeRoy), had been treated with something like reverence in the production number "Remember My Forgotten Man." Had sensibilities been so hardened over time that the victims of the Depression could be treated so lightly? In any case, My Man Godfrey was a big hit, and was the first movie to have Oscar nominations -- for Powell, Lombard, Auer, and Brady -- in all four acting categories. It was also nominated for director and screenplay, though not for best picture.

Sunday, October 23, 2016

Kagemusha (Akira Kurosawa, 1980)

In the climactic moments of Kagemusha director Akira Kurosawa does something I don't recall seeing in any other war movie: He shows the general, Katsuyori (Ken'ichi Hagiwara) sending wave after wave of troops, first cavalry, then infantry, against the enemy, whose soldiers are concealed behind a wooden palisade, from which they can safely fire upon Katsuyori's troops. It's a suicidal attack, reminiscent of the charge of the Light Brigade, but Kurosawa chooses not to show the troops falling before the gunfire. Instead, he waits until after the battle is over and Katsuyori has lost, then pans across the fields of death to show the devastation, including some of the fallen horses struggling to get up. It's an enormously effective moment, suggestive of the dire cost of war. The film's title has been variously interpreted as "shadow warrior," "double," or decoy." In this case, he's a thief who bears a remarkable resemblance to the formidable warlord Takeda Shingen and is saved from being executed when he agrees to pretend to be Shingen. (Tatsuya Nakadai plays both roles.) This masquerade is designed to convince Shingen's enemies that he is still alive, even though Shingen dies soon after the kagemusha agrees to the ruse. The impostor proves to be surprisingly effective in the part, fooling Shingen's mistresses and winning the love of his grandson, and eventually presiding over the defeat of his enemies. But he gains the enmity of Shingen's son, Katsuyori, who not only resents seeing a thief playing his father but also holds a grudge against Shingen for having disinherited him in favor of the grandson. So when the kagemusha is exposed as a fake to the household, he is expelled from it, and Katsuyori's arrogance leads to the defeat in the Battle of Nagashino -- a historical event that took place in 1575. The poignancy of the fall of Shingen's house is reinforced at the film's end, when his kagemusha reappears in rags on the bloody battlefield, then makes a one-man charge at the palisade and is gunned down. The narrative is often a little slow but the film is pictorially superb: Yoshiro Muraki was nominated for an Oscar for art direction, although many of his designs are based on Kurosawa's own drawings and paintings, made while he was trying to arrange funding for the film. Two American admirers, Francis Ford Coppola and George Lucas, finally came through with the financial support Kurosawa needed -- they're listed as executive producers of the international version of the film, having persuaded 20th Century Fox to handle the international distribution.

Saturday, October 22, 2016

Intolerance (D.W. Griffith, 1916)

|

| The Belshazzar's Feast set for Intolerance |

|

| Edwin Long, The Babylonian Marriage Market, 1875. |

Friday, October 21, 2016

Love & Friendship (Whit Stillman, 2016)

Jane Austen's greatest novels -- by which I mean Emma, Pride and Prejudice, Mansfield Park, and Persuasion -- do tend to run to formula. The heroines are all marriageable young women who for one reason or another are having trouble finding a mate. They are usually put in jeopardy of marrying scoundrels -- Emma to Frank Churchill, Elizabeth Bennet to Mr. Wickham, Fanny Price to Henry Crawford -- or fools -- Emma to Mr. Elton, Elizabeth to Mr. Collins -- or in Anne Elliot's case not at all, a calamitous fate in the world of the novels. Eventually, however, they find their Mr. Knightley or Darcy or Edmund or Capt. Wentworth and live happily ever after. The pattern is so familiar that it persists to this day in romance novels, but it's not why we read Jane Austen. We read her for the wit, the moral observations, the deft interplay of personalities, which is why even the best movies made from her books are slightly unsatisfying: Film can't do justice to what's on the page. And that's why I think Love & Friendship may be the best Jane Austen movie ever: What's on the page in its source, Lady Susan, the epistolary novella she never submitted to a publisher, departs radically from the formula. The titular heroine (played brilliantly in the film by Kate Beckinsale) is herself the scoundrel, more in the mold of Henry Crawford's sister, Mary, in Mansfield Park than any of Austen's more familiar heroines. And she winds up marrying the fool, the wealthy Sir James Martin (Tom Bennett), whom she originally planned as a husband for her daughter, Frederica (Morfydd Clark), after having courted Reginald DeCourcy (Xavier Samuel), who winds up marrying Frederica. Whit Stillman's screenplay is a brilliant transformation of what's on the pages of the source, where the point of view is limited to that of the letter writers. The freedom to manipulate point of view in the film allows him to play with inverting the formula: In the film, Reginald takes on the role usually played by Austen's heroines, i.e., almost marrying the scoundrel. With Bennett's considerable help, Stillman makes Sir James Martin into one of the funniest fools ever, so blithely out of it that he is astonished to learn that Frederica reads "both verse and poetry" and thinks that Moses delivered 12 commandments -- after being told that there are only ten, he tries to decide which two he should discard. He also winds up after his marriage to Lady Susan in a ménage à trois that includes Lord Manwaring (Lochlann O'Mearáin), but he remains apparently unaware that Manwaring is her real lover and the father of the child she is carrying. That last could never have found its way into print in Austen's day, of course, but Stillman succeeds in integrating it into a convincingly Austenian context. The performers, which also include Chloë Sevigny, Jemma Redgrave, James Fleet, and in a cameo role, Stephen Fry, are uniformly fine. If there is a flaw to the film, it may be that it's "rather too light, and bright, and sparkling," which is the criticism that Austen made of Pride and Prejudice. But if it sometimes feels like a parody of a Jane Austen novel, it's a masterly one.

Thursday, October 20, 2016

Hail the Conquering Hero (Preston Sturges, 1944)

What sort of nerve must it have taken to make a film that pokes fun at patriotism, mother love, small towns, political campaigns, and the Marines in the middle of World War II? Preston Sturges's film begins in a small nightclub, where a singer (Julie Gibson) and her backup group of singing waiters launch into a stickily sentimental song, "Home to the Arms of Mother" (music and lyrics by Sturges), whereupon John F. Seitz's camera begins a traveling shot from the group and down a long bar at the end of which we see Woodrow Lafayette Pershing Truesmith (Eddie Bracken) drowning his sorrows. When a group of six Marines on leave after having fought at Guadalcanal enters the bar, Woodrow buys a round for them, and is prodded into telling them his sad story: He joined the Marines, trying to follow in the footsteps of his father, a Marine who died in World War I, but was discharged because of chronic hay fever. But instead of returning home to the arms of mother, he went to work in a shipyard and arranged for a friend to send his letters to her from overseas, disguising the fact that he was no longer a Marine. One of the men, Sgt. Heppelfinger (William Demarest), learns that Woodrow's father was his old buddy who fought with him at Belleau Wood, while another, Bugsy (Freddie Steele), is appalled that Woodrow hasn't been home to see his mother since the start of the war. So the Marines collude to take an extremely reluctant Woodrow back to his hometown and pretend that he's a war hero who has just been discharged. Naturally, the plan backfires spectacularly when the whole town joins in the celebration and even railroads Woodrow into running against the corrupt mayor (Raymond Walburn). Speed is of the essence in a farce like this, because if anyone ever gave Woodrow a moment to talk, the whole thing would collapse like a soufflé. On the other hand, too much fast talk can be wearying, so Sturges introduces a romantic subplot: Feeling that he can never return home, Woodrow has written his girlfriend, Libby (Ella Raines), that he has met someone else, so Libby has gone and got herself engaged to Forrest Noble (Bill Edwards), the son of the town's corrupt mayor. To slow the pace down, Sturges introduces a long walk-and-talk tracking scene in which Libby, confused by her revived feelings for Woodrow, tries to sort things out with Forrest, but to no avail. It's a funny, beautifully written scene, but it doesn't quite work because neither Raines nor Edwards is up to the acting demands it puts on them -- I kept thinking how much better Joel McCrea and Claudette Colbert or Henry Fonda and Barbara Stanwyck would have played it. Bracken, however, is wonderful, as are Demarest, Steele, Walburn, and other members of Sturges's usual crew of brilliant character actors, including Franklin Pangborn as the harried planner of the celebration and Jimmy Conlin as the town judge. This was, sadly, the last film Sturges made under his Paramount contract, which he ended because of studio interference during the making of the movie. It objected, perhaps rightly, to Ella Raines's lack of star power, but also took the film out of Sturges's hands and edited it. After a couple of disastrous previews of the studio version, however, Sturges was called back in for rewrites and some new scenes. The revised Sturges version was a hit, and earned him an Oscar nomination for best screenplay.

Wednesday, October 19, 2016

Belle de Jour (Luis Buñuel, 1967)

Belle de Jour is a famously enigmatic film, venturing into (and often blurring) the space between reality and fantasy, between waking life and dreams. It has led a lot of people astray, into questions like: What's buzzing in the Asian client's box that so frightens the other prostitutes in the brothel, but so satisfies Séverine (Catherine Deneuve)? Why does Séverine so often hear cats meowing? What is the Duke (Georges Marchal) doing that so shakes the coffin in which he has posed Séverine and causes her to flee into the rain? Why is Pierre (Jean Sorel) so fascinated by the wheelchair that foreshadows his fate? How much of any of this is meant to be reality? Critics have been more or less preoccupied by these and other matters of speculation and interpretation for almost 50 years. But I, for one, am content to invoke Keats's "negative capability," which he defined as the ability of an artist to be "in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason." Of course, it would be abrogating the critics' responsibility if they failed to pursue the aesthetic and moral effects of the enigmas introduced into the film by Luis Buñuel and screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière. I'm arguing that their effect is collective and cumulative, that pursuing any one of these details in search of a definitive answer is like concentrating on the threads at the expense of seeing the tapestry. Belle de Jour is subject to all forms of analysis -- Freudian, Jungian, Lacanian, Marxist, feminist, you name it -- but without exhausting its possibilities to tantalize. I think Buñuel's major achievement in the film is in sticking to his roots in surrealism without resorting to surrealist clichés: Every scene, even the obvious fantasies like the one in which Séverine is pelted with muck by Pierre and Husson (Michel Piccoli), is grounded in actuality, down to the specific address and the mundane Parisian location given to the brothel run by Madame Anaïs (Geneviève Page). It's only in reflecting on the film that we begin to question which scenes are "real" and which aren't. Belle de Jour is one of those inexhaustible films that you revisit with the certain knowledge that it will look slightly different to you every time.

Tuesday, October 18, 2016

Madame de... (Max Ophuls, 1953)

The word "tone" is much bandied about by critics, myself included. We speak of a film as being "inconsistent in tone" or its "melancholy, despairing tone" or its "shifts in tone." But ask us -- or, anyway, me -- what we mean by the term, and you may get a lot of stammering and hesitation. Even my old copy of the Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics falls back on calling it "an intangible quality ... like a mood in a human being." So when I say that Madame de... is a masterwork in its manipulation of tone, you have to take that observation as a kind of awestruck, slightly inarticulate response to a film that begins in farce and ends in tragedy. The American title of the film was The Earrings of Madame de..., but to my mind that puts the emphasis on what is, in effect, merely a MacGuffin. The earrings were given to Countess Louise de... (Danielle Darrieux) by her husband, General André de... (Charles Boyer), on their wedding day. (Their full surname is coyly hidden throughout the film: A sound blots out the latter part of the name when it is spoken, and it is hidden by a flower when it appears on a place card at a banquet. The effect is rather like a newspaper gossip column trying to avoid a libel suit when reporting a scandal among the aristocracy.) The scandal is set in motion when Louise, a flirtatious woman with many admirers, decides to sell the earrings to pay off the debts she wants to hide from André. Their marriage has obviously come to a pause: Though they remain affectionate with each other, they have separate bedrooms and at night they talk to each other through doors that open on a connecting room. Louise takes the earrings to the jeweler (Jean Debucourt) from whom André originally purchased them. But when she tries to persuade André that she lost them at the opera and the "theft" is reported in the newspapers, the jeweler tries to sell them back to the general. To put an end to the business, André pays for them, then presents them to his mistress, Lola (Lia Di Leo), as a parting gift: Their affair over, she is leaving for Constantinople. There, Lola gambles them away, but they are bought by an Italian diplomat, Baron Donati (Vittorio De Sica), who is on his way to a posting in Paris. And of course Donati meets Louise, they fall in love, and he presents the earrings to her as a gift. Recognizing them, she has no recourse but to hide them, but they will resurface with fatal results. How Max Ophuls gradually shades this plot from a situation suited to a Feydeau farce into a poignant conclusion is a part of the film's magic. It depends to a great extent on the superb performances of Darrieux, Boyer, and De Sica, but also on Ophuls's typically restless camera, handled -- as in Ophuls's La Ronde (1950), Le Plaisir (1952), and Lola Montès (1955) -- by cinematographer Christian Matras, as it explores Jean d'Eaubonne's elegant fin de siècle sets. Much depends, too, on the film editor, Borys Lewin, who helps Ophuls accomplish one of the movies' great tours de force, following Louise and Donati as they dance what appears to be an extended waltz but gradually shows itself to be several waltzes taking place over the period of time in which they fall in love. It's a cinematic showpiece, but it's fully integrated into what has to be one of the great movies.

Monday, October 17, 2016

Dukhtar (Afia Nathaniel, 2014)

Sunday, October 16, 2016

Easy Living (Mitchell Leisen, 1937)

Easy Living is one of my favorite screwball comedies, but I once had a nightmare that took place in the set designed by Hans Dreier and Ernst Fegté for the film. It was the luxury suite in the Hotel Louis, with its amazingly improbable bathtub/fountain, and I dreamed that we had just bought a place that looked like it and were moving in. I don't remember much else, other than that I was terribly anxious about how we were going to pay for it. Most of my dreams are anxiety dreams, I think, which may be why I love screwball comedies so much: They take our anxieties about money and love and work, like Mary Smith (Jean Arthur) worrying about how she's going to pay the rent and even eat now that she's lost her job, and transform them into dilemmas with comic resolutions. Too bad life isn't like that, we say, but with maybe a kind of glimmer of hope that it will turn out that way after all. Easy Living, with its screenplay by Preston Sturges, is one of the funniest screwball comedies, but it's also, under Mitchell Leisen's direction, one of the most hilarious slapstick comedies. How can you not love a film in which a Wall Street fat cat (Edward Arnold) falls downstairs? Or the celebrated scene in which the little doors in the Automat go haywire, producing food-fight chaos that builds and builds? The fall of the fat cat and the rush on the Automat reveal that Easy Living was a product of the Depression, anxiety made pervasive and world-wide, when we needed hope in the form of comic nonsense to keep us going. This is also an essential film for those of us who love Preston Sturges's movies, for although he didn't direct it, his hand is evident throughout, not only in the dialogue but also in the casting, with character actors who would later form part of Sturges's stock company, Franklin Pangborn, William Demarest, and Robert Greig among them. Ray Milland displays a Cary Grant-like glint of amusement at what's going on, Luis Alberni spouts Sturges's wonderful malapropisms as the hotel owner Louis Louis, and Mary Nash brings the right amount of indignation and humor to her role as Arnold's wife. I only wonder why Ralph Rainger and Leo Robin weren't credited for their title song, which is heard (though without its lyrics), as background music throughout the film.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)