A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Monday, November 7, 2016

Excuses, Excuses

I watched Samurai Rebellion (Masaki Kobayashi, 1967) last night, but I'm not going to write about it today because I'm facing a deadline for a book review. Back with more posts after that's done.

Sunday, November 6, 2016

The Great Beauty (Paolo Sorrentino, 2013)

The great beauty referred to in the title of Paolo Sorrentino's film is Rome itself, which for millennia has transcended the ugliness that has overrun its seven hills. It's a city whose beauty and ugliness are seen in the film from the point of view of Jep Gambardella (Toni Servillo), who is celebrating his 65th birthday as the film begins. Jep first received acclaim 40 years earlier for a well-received novella, but the rest of his life has been spent as a celebrity journalist, interviewing and gossiping about the rich and famous. This career has earned him his own fame and fortune -- he lives in a luxurious apartment whose balcony overlooks the Colosseum. He's a bit like a straight Roman Truman Capote. The Rome in which Jep moves is filled with absurdity and excess: a performance artist who runs headlong into an ancient aqueduct; a little girl who has made millions by splashing canvases with paint and then smearing and tearing at them in a tantrum; a doctor who maintains a kind of assembly-line botox clinic in which patrons take numbers as if they were waiting in a delicatessen; a saintly centenarian Mother Teresa-style missionary whose spokesman is an oily dude with a shark-toothed grin; an archbishop considered next in line for the papacy who can only talk about food; and hordes of glitterati who spout inanities that they think will pass for wit. The Great Beauty is a satire, of course, but oddly it's a satire with heart: Jep Gambardella's long-since-broken heart. Servillo is terrific in the key role: elegant and cynical, but also capable of exposing idiots for what they are. Jep and the film in which he appears have obviously been compared to Marcello Mastroianni's character in La Dolce Vita (Federico Fellini, 1960), but Jep is less jaded than Marcello, less ground down by the decadence. And Sorrentino's view of his Rome is more genially ironic than Fellini's carnival of grotesques. Beautifully filmed by Luca Bigazzi, with a score by Lele Marchitelli augmented with works by contemporary composers like David Lang, Arvo Pärt, John Taverner, Henryk Górecki, and Vladimir Martynov, The Great Beauty was a deserving winner of the 2013 Oscar for foreign-language film.

Saturday, November 5, 2016

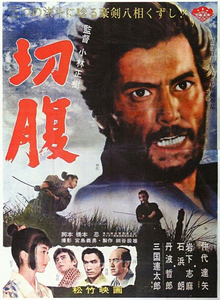

Harakiri (Masaki Kobayashi, 1962)

A study in tragic irony, Harakiri was intended as a commentary on Japan's history of hierarchical societies, from the feudal era through the Tokugawa shogunate and down to the militarism that brought the country into World War II and finally the corporate capitalism in which the salaryman becomes the latest iteration of the serf, pledging fidelity to a ruling lord. Working from a screenplay by Shinobu Hashimoto from a novel by Yasuhiko Takiguchi, director Masaki Kobayashi sets his film on a steady pace that at first feels static. There are long scenes of talk, with little moving except the camera's slow pans and zooms. But as Kobayashi's protagonist, Hanshiro Tsugumo (brilliantly played by Tatsuya Nakadai), tells his harrowing tale of loss, the film opens out into beautifully crafted scenes of action, as well as one terrifying and painful scene of cruelty, in which a man is made to commit the title's ritual disembowelment with a sword made of bamboo. Although there is an extended fight sequence in which Hanshiro takes on the entire household of the Ii clan, the true climax of the film is the duel between Hanshiro and Hikokuro Omodaka (Tetsuro Tanba), the greatest swordsman in the Ii household. Especially in this scene, the cinematography of Yoshio Miyajima makes a brilliant case for black and white film, aided by the editing of Hisashi Sagara that cuts between the dueling men and the waving grasses on the windswept hillside where the fight takes place. Harakiri is one of the best samurai films ever made, but even that observation contains its own note of irony, since Kobayashi's aim with the film is to validate his protagonist's assertion that "samurai honor is ultimately nothing but a façade."

Friday, November 4, 2016

A War (Tobias Lindholm, 2015)

|

| Pilou Asbæk in A War |

Maria Pederson: Tuva Novotny

Martin R. Olsen: Søren Malling

Kajsa Danning: Charlotte Munck

Najib Bisma: Dar Salim

Lasse Hassan: Dulfi Al-Jabouri

Director: Tobias Lindholm

Screenplay: Tobias Lindholm

Cinematography: Magnus Nordenhof Jønck

A war movie that appeals more to the brain and the heart than to the viscera, Tobias Lindholm's A War raises some haunting ethical questions about war and justice. Claus, a Danish officer, while leading a detachment of his men in an assault on the Taliban, calls in an air strike on what he believes to be the source of the gunfire that has pinned them down and left one of his soldiers critically injured. Under cover of the bombing they are able to make it to the rescue helicopter, but Claus is later charged with a war crime: There is no evidence that the gunfire came from the village where the bombing killed civilians, women and children. At the trial, held back in Denmark, Claus is acquitted after one of his men perjures himself, claiming that he had seen a muzzle flash from the village, justifying Claus's decision. But it's not a "happy ending." The film has provided many emotional justifications for Claus's action: We earlier saw Lasse, the critically injured man whose life Claus saves by calling in the air strike, in extreme emotional distress after witnessing the death of one of his fellow soldiers who stepped on a land mine. Claus had comforted Lasse, but nevertheless insisted that he go on this near-fatal mission. Claus also struggles with guilt because he had turned away an Afghan family seeking refuge in the military compound: They had been threatened by the Taliban after they sought medical help for their little girl, suffering from a bad burn. Reconnoitering for the assault, Claus discovers that the Taliban had made good on their threat and slaughtered the family. Claus is also struggling with pressure from home, where his wife, Maria, is having trouble looking after their three small children: The middle child is acting out at school, and the youngest, a toddler, has had to have his stomach pumped after swallowing some pills. Writer-director Lindholm beautifully balances the combat scenes with those depicting Maria's difficulties at home. But he also stages a fine courtroom scene in which the prosecutor demonstrates that Claus is in fact guilty as charged: There was no evidence that the destroyed village was the source of the gunfire that pinned down Claus and his men. So, even though his acquittal comes at the expense of a witness's lie, are we right to feel good that Claus is free and able to look after his family? There are hints that Claus will never be free of the burden of guilt: After the verdict, he is seen tucking in his children at night. The feet of one of the children are sticking out from under the covers, and Claus carefully pulls the blanket over them. It's a moment that echoes the earlier scene in which Claus discovered the slaughtered Afghan family: One of the dead children's feet were protruding from the covers just like Claus's own child's. Lindholm beautifully trusts the audience to recall this detail, without having Claus flash back to it himself, but the final scene of the film, in which Claus sits alone on his patio, smoking, suggests that he will always be alone with his guilt.

Thursday, November 3, 2016

The Navigator (Donald Crisp and Buster Keaton, 1924)

Buster Keaton always makes me grin. The first time I did it while watching The Navigator was when rich twit Rollo Treadaway (Keaton) puts on a straw hat and then gracefully steadies it with the crook of his cane. Keaton can do more with a hat -- or, later, hats -- than anyone, even Cary Grant with the outsize hat in my favorite scene in The Awful Truth (Leo McCarey, 1937). And then the grin became a guffaw when Rollo gets in his chauffeur-driven limousine to go propose to Betsy O'Brien (Kathryn McGuire), another rich twit. The limo starts out and immediately makes a U-turn to the other side of the street, where Betsy lives. It's not just Keaton's physical grace and dexterity, for all that he pretends to be a klutz, or even the unexpectedness of some of the gags that make me so happy. It's primarily the sense of joy I get in watching a kid play with his toys. For Keaton has such wonderful toys in his movies. In The General (Keaton and Clyde Bruckman, 1926) he has an entire antique railroad train to play with (and destroy); in Go West (Keaton, 1925) it's a herd of cattle; in Steamboat Bill Jr. (Charles Reisner but really Keaton, 1928) it's a town in a terrific windstorm. So you can imagine his delight when he heard than a retired Army transport ship was for sale, and he could refit this enormous toy into the cruise ship Navigator and do with it as he pleased. And he certainly made the most of it, using the exposed decks and corridors for a hilarious game of unwitting hide-and-seek between Rollo and Betsy, turning the galley into an improbable kitchen for two rich twits who have never had to cook their own breakfast, and donning an old-fashioned diving suit for an extended underwater sequence: Keaton does the only pratfall I've ever seen anyone do underwater and in a diving suit, legs straight out as all the great slapstick comics did pratfalls. There are some occasional slow moments: The battle with the "cannibals" goes on much too long. But the pacing mostly stays so rapid that you want to rewind and watch some scenes to see what you miss -- a luxury denied his original audiences, who had to stay and sit through it twice. McGuire also appeared in Keaton's Sherlock Jr. (1924), proving herself what any of Keaton's leading ladies had to be: game for almost anything, including repeated dives and dunkings. Although Donald Crisp, better known to us as an actor, was an experienced director -- he has 72 IMDb directing credits from 1914 through 1930 -- he turned out to be a mismatch with Keaton, who took over and finished the film, sometimes reshooting scenes that Crisp had directed.

Wednesday, November 2, 2016

Oedipus Rex (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1967)

Seeing Julian Beck as Tiresias in Pier Paolo Pasolini's Oedipus Rex reminded me of an excruciatingly boring evening I spent in Brooklyn in 1968. Some friends had invited me to go with them to see Beck's Living Theatre perform their play Paradise Now, which as I recall featured the semi-naked company, including some pale and pimply dudes in jockstraps, wandering through the audience, yelling at us about our bourgeois complacency. Those who know me will realize that this is not my sort of thing at all. I realize now that Beck and Judith Malina had a tonic effect on theater with their avant-garde productions, and I salute them for that, but I was not receptive to their efforts on that evening. Fortunately, Pasolini's Oedipus, though infused with some of the radicalism of the Living Theatre, is not at all boring. It's sometimes raw and rough-edged, especially by standards of mainstream cinema. The Technicolor camerawork -- the cinematographer is Giuseppe Ruzzolini -- is often very beautiful, with its astonishing images of the Moroccan desert and ancient buildings, but there are some bobbles in the hand-held camera sequences that move beyond shakycam into wobbly-out-of-focuscam. Franco Citti, who made his debut in the title role of Pasolini's Accattone (1961) and appeared in many of his other films, is a bit out of his depth as Oedipus, but Silvana Mangano is an impressive-looking Jocasta, and Beck is a suitably foreboding Tiresias. Pasolini's screenplay does justice to its Sophoclean origins as well as to the perdurable myth, although the frame story that begins in Italy during the Mussolini era, with the Fascist anthem "Giovinezza" on the soundtrack, and ends in Pasolini's present seems extraneous. But the truly astonishing contribution to the film was made by costume designer Danilo Donati, whose eerie designs, seemingly cobbled together from scrap metal, clay, and leaves and branches, don't belong to any particular era but have the right aura of primitive myth. Some examples:

|

| The Oracle of Apollo in Oedipus Rex |

|

| Silvana Mangano as Jocasta |

|

| Headdress for a priest |

Tuesday, November 1, 2016

Star Wars: Episode VII -- The Force Awakens (J.J. Abrams, 2015) revisited

When I blogged about seeing Star Wars: Episode VII -- The Force Awakens, to give it its full and exhausting title, 10 months ago, I was more involved in the novelty of seeing it in a theater and in 3-D than in commenting on the film itself. "I look forward to seeing the movie again, but this time in the comfort of my home and on a smaller 2-D screen," I said then, predicting that it would "play just as well there." So the time has come, and Starz is running it almost every day on one of its many channels, so I availed myself of the opportunity, and I think I was mostly correct. The flat version is less awe-inspiring than the three-dimensional one, but I've long since got beyond the excitement of having lightsaber beams waved in my face, and to my mind the added depth of the images is counteracted by a sense of their insubstantiality: Is it only the force of long habit and familiarity that makes two-dimensional films seem more like documented reality? The 2-D Episode VII stands up because J.J. Abrams knows the grammar of film: the cutting and pacing that has brought excitement to movies ever since Griffith and Eisenstein and other first learned to use them. In 3-D there's always going to be something a little disorienting about the shift from a close-up to a long shot, for example. Perhaps a grammar of 3-D will be developed that lets filmmakers use it as effectively as they do in two dimensions, but that time has yet to come. As for the film itself, it had to do two things: It had to tie the new material to the core trilogy -- I mean Episodes IV-VI, of course -- and it had to whet our appetites for more new stuff. It succeeds on both counts, partly by bringing back Han (Harrison Ford), Leia (Carrie Fisher), and, albeit briefly, Luke (Mark Hamill), and the leitmotifs of John Williams's score, but also by pretty much shamelessly borrowing from what's now called Star Wars: Episode IV -- A New Hope (George Lucas, 1977). (I will always call it just Star Wars.) As I said in my first post, VII is pretty much a remake of IV: Both have "the young hero on a desert planet, the messenger droid found in the junkyard, the gathering of a team to fight the black-clad villain, and the ultimate destruction of a giant weaponized space station." VII also echoes the Oedipal conflict of the subsequent episodes of the core trilogy, with the conflict of father Han and son Kylo Ren (Adam Driver) echoing that of Darth Vader and Luke. What we have to look forward to is some account of Ren's (or Ben's) fall to the Dark Side and some resolution of that character's patricidal act. We also have to find out who or what Supreme Leader Snoke (Andy Serkis) is. Is there a little old man lurking behind what seems to be a hulking hologram, like the Wizard of Oz? And what are the backstories of Poe Dameron (Oscar Isaac), Finn (John Boyega), and Rey (Daisy Ridley)? And what accounts for the luxury casting of the ubiquitous Domhnall Gleeson as the relatively secondary figure General Hux? And why waste a beautiful Oscar winner like Lupita Nyong'o in voicing Maz Kanata -- another character whose backstory needs to be told? So our appetites are whetted, and not just for further adventures of Luke Skywalker.

Monday, October 31, 2016

Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! (Pedro Almodóvar, 1989)

The vivid Technicolor imagination of Pedro Almodóvar doesn't serve him as well in Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! as it did in his immediately previous hit film Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (1988). This film feels rather like an uneasy mashup of a romantic comedy and a bondage porno. Actually, "porno" is too strong a word, for even though Tie Me Up! received an NC-17 rating on its release in the United States, there's very little in it that can't be seen any night on the mainstream shows of pay-cable outlets like HBO and Showtime. The most explicit scenes involve Marina (Victoria Abril) taking a bath with a mechanical tub toy shaped like a frogman that nuzzles into her private parts -- a scene that's more funny than erotic -- and an extended sex scene with Marina and Ricky (Antonio Banderas) that's undeniably erotic but not especially revealing -- it mainly shows their upper bodies, except for an overhead shot that reveals Banderas's posterior. What's more objectionable -- especially in the context of today's renewed dialogue about rape and sexual harassment in the context of the presidential campaign -- is the film's central plot premise: Ricky, who has just been released from a mental institution (whose director and nurses he has been happily bedding), kidnaps film star Marina, whom he once picked up and had sex with during an escape from the institution. In the course of trying to make Marina fall in love with him, Ricky keeps her tied up. Eventually, she finds herself falling in love with him, and the film ends with Ricky going off to live with her and her family. It can be argued that the premise is freighted with irony: Ricky's attempt to win Marina leads to his being severely beaten by the drug dealers he goes to see to procure something to relieve her toothache and other pains -- as a recovering drug addict, Marina finds almost any painkiller short of morphine ineffective. The kidnapper gets a measure of punishment for his misdeed, in other words. But the film's unsteady tone and the somewhat pat "happy ending" don't overcome the essentially distasteful sexual politics of the premise. Though it's a misfire, the movie gets good performances out of Banderas and Abril, as well as Loles León as Marina's exasperated sister, Lola, and Francisco Rabal as Marina's director, desperately trying to control the chaotic production of what may be his last film. The brightly colorful sets by production designer Esther Garcia, art director Ferran Sánchez, and set decorator Pepon Sigler, and the cinematography by José Luis Alcaine are also a plus.

Sunday, October 30, 2016

The Lavender Hill Mob (Charles Crichton, 1951)

The late 1940s and early 1950s were a golden age for British film comedy, and Alec Guinness was right at the heart of it with his roles in The Lavender Hill Mob, Kind Hearts and Coronets (Robert Hamer, 1949), The Man in the White Suit (Alexander Mackendrick, 1951), The Captain's Paradise (Anthony Kimmins, 1953), and The Ladykillers (Mackendrick, 1955). It was the period when comic actors like Margaret Rutherford, Terry-Thomas, Alastair Sim, and the young Peter Sellers became stars, and British filmmakers found the funny side of the class system, economic stagnation, and postwar malaise. For it wasn't a golden age for Britain in other regards. Some of the gloom against which British comic writers and performers were fighting is on evidence in The Lavender Hill Mob, but it mostly lingers in the background. As the movie's robbers and cops career around London, we get glimpses of blackened masonry and vacant lots -- spaces created by bombing and still unfilled. The mad pursuit of millions of pounds by Holland (Guinness) and Pendlebury (Stanley Holloway) and their light-fingered employees Lackery (Sidney James) and Shorty (Alfie Bass) seems to have been inspired by the sheer tedium of muddling through the war and returning to the shriveled routine of the status quo afterward. Who can blame Holland for wanting to cash in after 20 years of supervising the untold wealth in gold from the refinery to the bank? "I was a potential millionaire," he says, "yet I had to be satisfied with eight pounds, fifteen shillings, less deductions." As for Pendlebury, an artist lurks inside the man who spends his time making souvenir statues of the Eiffel Tower for tourists affluent enough to vacation in Paris. "I propagate British cultural depravity," he says with a sigh. Screenwriter T.E.B. Clarke taps into the deep longing of Brits stifled by good manners -- even the thieves Lackery and Shorty are always polite -- and starved by the postwar rationing of the Age of Austerity. Clarke and director Charles Crichton of course can't do anything so radical as let the Lavender Hill Mob get away with it, but they come right up to the edge of anarchy by portraying the London police as only a little more competent than the Keystone Kops. The film earned Clarke an Oscar, and Guinness got his first nomination.

Saturday, October 29, 2016

Oldboy (Park Chan-wook, 2003)

It's about as improbable a premise for a thriller you'll find: A man, out on a drunken spree, wakes up imprisoned in what looks like a cheap hotel room where he stays, not knowing who put him there or why, for 15 years. His only contact with the outside world is a television set; his food is slipped to him through a slot in the door, and occasionally gas that puts him to sleep is pumped in the room so that it can be cleaned while he is unconscious. Then one day he is suddenly released and provided with cash and a cell phone. He begins to hunt compulsively for answers about who has done this to him. It's a mad plot, riffing on themes of guilt and obsession that are worthy of Kafka or Dostoevsky, but instead are cast in the idiom of horror movies and martial arts films. Eventually, the protagonist, Oh Dae-su (Choi Min-sik), will find the answers to what he seeks, but the truth will be more shattering than satisfying. Oldboy won the Grand Prix at the Cannes Festival, and no one who knows movies will be surprised to find that the jury was presided over by Quentin Tarentino, who gets the same inspiration from violent pop culture that Park Chan-wook demonstrates. The screenplay for Oldboy, on which Park shares credit with Lim Chun-hyeong and Hwang Jo-yun, was based on a Japanese manga. Park has said that he named his protagonist Oh Dae-su as a near homonym for Oedipus, who shared a similar fate when he discovered the truth, but Oldboy is closer to Saw (James Wan, 2004) than to Sophocles. Nevertheless, Oldboy has provocative things to say about guilt and revenge, and Choi's performance as the abused and haunted Dae-su is superb. Yu Ji-tae is suavely menacing as the villain, and Kang Hye-jeong is touching as Mi-do, who aids Dae-su in his quest. The often startlingly grungy production design is by Ryu Seong-hie and the cinematography by Chung Chung-hoon. There is a stunningly accomplished long take in the middle of the film in which the camera follows Dae-su as he single-handedly battles an army of opponents in a hallway that stretches across the wide screen like a frieze on the entablature of a temple. For once, however, a tour-de-force display of cinema technique doesn't overwhelm the rest of the film.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)