|

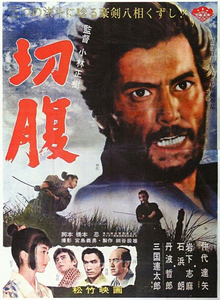

| Koji Takahashi and Jitsuko Yoshimura in Samurai Spy |

Cast: Koji Takahashi, Shintaro Ishihara, Eitaro Ozawa, Kei Sato, Mutsuhiro Toda, Tetsuro Tanba, Eiji Okada, Seiji Miyaguchi, Minoru Hodaka, Misako Watanabe, Yasunori Irikawa, Jitsuko Yoshimura, Jun Hamamura.

Screenplay: Yoshiyuki Fukuda,

based on a novel by Koji Nakada.

Cinematography: Masao Kusugi.

Art direction: Junichi Osumi.

Film editing: Yoshi Sugihara.

Music: Toru Takemitsu.

Samurai Spy begins with a history lesson: a voiceover telling us about the chaos that set in after the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600 and the rivalry between the Tokugawa Shogunate and the Toyotomi Clan. Ordinarily, this kind of information would be helpful to the Western viewer in sorting out what takes place in the film, but such a welter of names and allegiances follows that it left me in a muddle -- one admirer of the film even suggests taking notes. But the point being made by director Masahiro Shinoda seems to be that even the participants in the conflicts of the time weren't sure who was on whose side at any given point. It came down to a spy vs. spy situation, with double crosses at every turn. Let it suffice to say that the central figure in the film is Sasuke Sarutobi, played with steely authority by Koji Takahashi, a spy for his clan who has wearied of unending war, but nevertheless gets caught up in its intrigues. At this point, I simply let myself go with the flow of the film, which is often extraordinarily beautiful. Shinoda intentionally underplays the action usually associated with samurai movies: One fight takes place in a field swept by fog, a kind of now-you-see-it, now-you-don't tease that adds to the film's essential point that in warfare it's not always clear who are the winners and who the losers. Another sequence, beautifully filmed by Masao Kusugi, involves a duel between two men that's viewed from a distance: We see them as small almost antlike figures on a hillside, warily circling each other to the point that we don't know who is who. The nature that surrounds them is blithely indifferent to what seems so important to the combatants. Shinoda uses sound eloquently to reinforce this theme, sometimes introducing the call of a bird in the background to emphasize the beauty that's being violated by mere human concerns. And the movie is certainly flavored by Toru Takemitsu's score. Shinoda is often a difficult filmmaker to comprehend, and I wouldn't recommend his films -- with the possible exception of

Pale Flower (1964), which seems to me the most American-inflected of the movies of his that I've seen -- to someone just starting out with Japanese films, but

Samurai Spy has incidental pleasures even when you don't quite follow what's going on. Just don't expect the clarity of a Kurosawa-style samurai film.