A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Sunday, January 22, 2017

Bad Education (Pedro Almodóvar, 2004)

In the middle of Pedro Almodóvar's Bad Education, two men go into a theater that's holding a film noir festival. When they come out later, one says, "I kept having the feeling those films were about us." Indeed, if Almodóvar's movie is inspired by anything, it's film noir, but filtered through the Technicolor movies made by Alfred Hitchcock in the 1950s. The score by Alberto Iglesias often echoes the melancholy longing of Bernard Herrmann's music for Vertigo (Hitchcock, 1958). The intricate plot for Bad Education begins when a young man (Gael García Bernal) comes to the offices of film director Enrique Goded (Fele Martínez) and identifies himself as Goded's old school friend Ignacio Rodriguez. He doesn't call himself Ignacio anymore, he says. Instead, he goes by his stage name, Ángel Andrade, and he's hoping that Goded will cast him in his next film. Goded is more than surprised to see his old schoolmate -- in fact, he tells his assistant and current lover, Martín (Juan Fernández), Ignacio was his first love -- but he's currently experiencing a creative block and isn't hiring anyone now. So the actor leaves Goded a manuscript of a story he has written. Part of it, he says, is about their school days, and the rest is fiction based on what he thinks might have happened when they grew up. Goded reads the manuscript and is so impressed by the story it tells that he is determined to film it. And so begins an intricate film about memory, imagination, deception, betrayal, obsession, and revenge that centers on a pedophile priest's molestation of his young students. Bad Education was originally given an NC-17 rating by the Motion Picture Association of America for "explicit sexual content," but I suspect it was mostly because the sexual content involves two men. The rating was eventually reduced to R. The performance by García Bernal is spectacular: He manages several identities while retaining the core essential to all of them. Like most Almodóvar films, Bad Education is alive with bright primary colors -- the cinematography is by José Luis Alcaine, the art direction by Antxón Gómez, and the set decoration by Pilar Revuelta, with costumes designed by Paco Delgado and Jean-Paul Gaultier -- but the brightness only serves to heighten the shadows.

Saturday, January 21, 2017

The Gay Divorcee (Mark Sandrich, 1934)

Obviously, The Gay Divorcee wouldn't pass muster as the title for a heterosexual romantic comedy today, but the film's producers had to jump a few hurdles even in 1934, when the Hays Office censors were about to yield to the much stricter Production Code. The title of the Broadway musical on which the movie was based was Gay Divorce, and Catholic censors were strictly opposed to the idea that divorce could be anything other than a sin. However, assuming that she'd done her penance, a divorcee could be gay (in the older sense), just as Franz Lehár's old operetta asserted that a widow could be merry. This was the first teaming of Fred Astaire with Ginger Rogers in which they were the stars: They had been supporting players in their previous film, Flying Down to Rio (Thornton Freeland and George Nicholls Jr., 1933), and their dance numbers had caused such a sensation that RKO was eager to craft a musical around them. Pandro S. Berman, head of production at the studio, purchased the rights to Gay Divorce, in which Astaire had been the star on Broadway, and put a team of writers to work revising the musical's book by Dwight Taylor. The Broadway version had a score by Cole Porter, but all but one of the songs were jettisoned for the film. That song was the best, however: "Night and Day," which gave the stars their first great fall-in-love pas de deux. The screenplay, by many studio hands, takes the farcical premise of the play: Mimi Glossop (Rogers), seeks a divorce from her husand, and since they're in England, where the only justification for divorce is adultery, she, with the help of her Aunt Hortense (Alice Brady) and the lawyer Egbert Fitzgerald (Edward Everett Horton), arranges to be caught in a hotel room with a professional co-respondent, Rodolfo Tonetti (Erik Rhodes, who also played the role on Broadway). Meanwhile, however, she has fallen in love with Guy Holden (Astaire), an American she has just met -- and, of course, met cute. Through a sequence of screwball accidents, she winds up thinking that he's the co-respondent, and is disgusted that he should have such a sordid job. Eventually, everything is sorted out with the help of a hotel waiter (Eric Blore, also from the Broadway cast). In the middle of everything, there's a 20-minute-long production number centered on the film's big song, "The Continental," for which composer Con Conrad and lyricist Herb Magidson won the first Oscar ever given for a song written for a movie. The Gay Divorcee would rank with the best Astaire-Rogers films if it had a better score. Aside from "Night and Day," the rest are mostly forgettable novelty numbers, like "Let's K-nock K-nees," which is performed by a then-unknown Betty Grable with Horton and a gang of chorus members. Still, the movie lifted my spirits on Inauguration Night the way it must have soothed people's feelings during the Depression.

Friday, January 20, 2017

The Lives of Others (Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck, 2006)

Amid the almost universal acclaim, including a best foreign-language film Oscar, for Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck's The Lives of Others, there were some complaints from residents of the former East Germany that the writer-director was not as hard on his Stasi snoop, Gerd Wiesler (Ulrich Mühe), as he should have been. This is my second viewing of the film -- I saw it when it first appeared on DVD -- and I tend to agree. The movie as a whole is chilling -- well-plotted and well-acted -- but I'm not entirely convinced this time around by Wiesler's change of heart regarding the people he's surveiling: the playwright Georg Dreyman (Sebastian Koch) and his lover, the actress Christa-Marie Sieland (Martina Gedeck). At the start of the film, when we first see Wiesler teaching a class to Stasi-spy hopefuls, he's the perfect cold gray participant in a monstrous system of internal domestic espionage. But later, as he learns not only that the motive for spying on Dreyman and Sieland is not merely political but also sexual -- the minister of culture, Bruno Hempf (Thomas Theime) wants Dreyman eliminated so he can have Sieland all to himself -- he begins to be disillusioned with his work. And after a friend of Dreyman's, the blacklisted theater director Albert Jerska (Volkmar Kleinert), commits suicide and Dreyman sits down at the piano to play a piece of music -- composed for the film by Gabriel Yared -- called Sonata for a Good Man that Jerska had given him, Wiesler betrays the first real emotion we see from him in the film: A tear rolls down his cold gray face. Donnersmarck has said that he was inspired by Lenin's statement -- referred to in one point in the film -- that he had to give up listening to music like Beethoven's "Appassionata" sonata because it humanized him, distracting him from the task of revolution. On the other hand, we have all heard the stories of Nazi concentration camp commandants who read Schiller and Goethe and listened to Mozart and Schubert and were never deterred from their horrendous work by it. The flaw in Donnersmarck's film, I think, is that despite Mühe's brilliant performance as Wiesler, we never get enough of his backstory to suggest why he should be suddenly so vulnerable to sentiment. How could he have risen in the ranks of the Stasi to the point that he became not only a trusted agent but also an instructor of future agents if he has this key weakness? On the other hand, it's not a crippling flaw, thanks to exceptional performances and well-handled suspense.

Thursday, January 19, 2017

The Ascent (Larisa Shepitko, 1977)

|

| Boris Plotnikov in The Ascent |

Wednesday, January 18, 2017

The Last Métro (François Truffaut, 1980)

Watching The Last Métro only a day after The Sorrow and the Pity (Marcel Ophüls, 1969) was instructive, if a little bit unfair to François Truffaut's romantic backstage drama. The two films deal with the same milieu, France during World War II, but with such differing approaches that the stark devotion to ferreting out the truth in Ophüls's film makes Truffaut's dramatization of the plight of a Jewish theater owner and his company feel more glossy and sentimental than it perhaps really is. Truffaut, who was born in 1932, was only a boy during the war, so he can't be expected to have the kind of first-hand awareness of events that the adults pictured in his film possess. Consequently, his own preoccupation, the world of actors and directors, takes precedence in the film over the suffering people endured under the Nazis. He has admitted in interviews that The Last Métro is a kind of companion film to Day for Night (1973), his behind-the-camera account of making a movie. What he does recall is the theater -- in his case the movie theater rather than the legitimate stage -- was a kind of refuge from hardship, the hunger and cold brought about by wartime rationing. People gathered in theaters for communal warmth. The story is principally about an actress, Marion Steiner (Catherine Deneuve), who is trying to keep the theater that was run before the war by her husband, Lucas (Heinz Bennent), open. Lucas, who is Jewish, is rumored to have fled to America, but in fact he is hiding in the cellar of the theater while Marion, with the help of the rest of the regular company, stages a play. The director, Jean-Loup Cottins (Jean Poiret), is working from the notes Lucas made on the play before his disappearance. Cottins has his own dangerous secret: He's gay. A new leading man, Bernard Granger (Gérard Depardieu), joins the company, and inevitably a tension develops between him and Marion. Meanwhile, Lucas has figured out ways to listen in on rehearsals and make suggestions to Marion that she passes along to Cottins, who is unaware of Lucas's hiding place. Marion also has the difficulty of dealing with the authorities, who could close the theater at any moment, especially when the influential critic Daxiat (Jean-Louis Richard), a collaborator with the Nazis, takes an interest in her and the play. What takes place on stage, namely the sexual tension between the characters played by Marion and Bernard, often mirrors what's happening backstage. The Last Métro is a well-crafted movie -- Truffaut wrote the screenplay with Suzanne Schiffman -- that was France's entry for the best foreign-film Oscar and won a raft of the French César Awards, including one for cinematographer Nestor Almendros.

The Sorrow and the Pity (Marcel Ophuls, 1969)

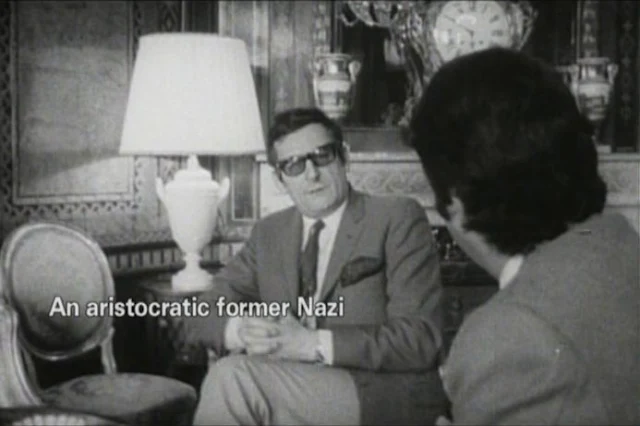

|

| Christian de la Mazière, one of those interviewed in The Sorrow and the Pity |

Tuesday, January 17, 2017

Battleship Potemkin (Sergei Eisenstein, 1925)

A perennial on "best films in history" lists, Battleship Potemkin is certainly one of the best-crafted movies ever. No matter how hokey and manipulative it seemed, I sat enthralled through my most recent viewing as the pounding, throbbing endless crescendo of music and editing surged toward the political victory of the Potemkin over the Czar's fleet. (The music on this version was Edmund Meisel's, which was performed at the Berlin premiere in 1926.) Because of the celebrated "Odessa Steps" sequence, which is cited in every textbook on editing and montage and in every tribute to Sergei Eisenstein or documentary about propaganda, I had forgotten that the real climax of the film is its final sequence. I had also forgotten how truly epic the film feels, with the great massing of crowds before the massacre on the steps. But is it a great film? Not if you're judging a film by any standard other than the way it gets blood pumping. It lacks insight into any human emotion other than resentment and the herd instinct. It's a masterpiece of propaganda. As with other such masterpieces, such as Leni Riefensthal's Triumph of the Will (1935), it lies to us. Which is all right, as long as we know it's lying and can keep our eye on the truth.

Joy (David O. Russell, 2015)

A thoroughly conventional movie with an exceptional cast that features what seems to be the core of writer-director David O. Russell's stock company, Jennifer Lawrence and Bradley Cooper, Joy is the kind of feel-good underdog-against-the-odds movie with screwball touches that could have been made at almost any time in Hollywood history. I can easily imagine it in the 1940s with Rosalind Russell and Fred MacMurray, for example. Joy Mangano (Lawrence) was a brilliant student in high school, but she didn't go on to college, and now struggles to make ends meet, while dabbling with ideas for inventions. A divorcee, she lives in an unusual household: In addition to her two children and her grandmother (Diane Ladd), the ménage also includes Joy's mother (Virginia Madsen), who spends her days in bed watching soap operas, and Joy's ex-husband (Edgar Ramirez), who lives in the basement. Joy's father (Robert De Niro) also joins the household after splitting from his latest wife, but he soon takes up with Trudy, a wealthy widow (Isabella Rossellini). When Joy comes up with the idea for a self-wringing mop, Trudy agrees to help finance it. Joy has to contract the manufacture of some of the mop's parts, and she struggles to market it until the idea comes to sell it on TV. She approaches the QVC shopping channel, where an executive, Neil Walker (Cooper), takes an interest in the product. It becomes a big seller, but then the company Joy contracted to make the parts claims ownership of the design. Facing bankruptcy, Joy fights the claim, wins, and becomes a huge success, marketing other household products. There's a real-life Joy Mangano on whose story the film is based, with the usual disregard for accuracy. Lawrence got an Oscar nomination for her performance, which is, as always, wonderful. She gives the film more than it deserves, and the supporting cast measures up to her. But there are few surprises in the story or in Russell's treatment of it, unlike his previous films with Lawrence and Cooper, Silver Linings Playbook (2012) and American Hustle (2013).

Monday, January 16, 2017

The Antoine Doinel Cycle

The 400 Blows (François Truffaut, 1959)

Antoine Doinel: Jean-Pierre Léaud

Julien Doinel: Albert Rémy

Gilberte Doinel: Claire Maurier

René Bigey: Patrick Auffay

M. Bigey: Georges Flamant

Director: François Truffaut

Screenplay: François Truffaut, Marcel Moussy

Cinematography: Henri Decaë

Music: Jean Constantin

One of the unquestioned great movies, and one of the greatest feature-film directing debuts, The 400 Blows would still resonate with film-lovers even if François Truffaut hadn't gone on to create four sequels tracking the life and loves of his protagonist, Antoine Doinel (Jean-Pierre Léaud). There are, in fact, those who think that the last we should have seen of Antoine was the haunting freeze-frame at the end of the film. But Antoine continued to grow up on screen, and perhaps more remarkably, so did Léaud, carving out his own career after his debut as a 13-year-old. (It's hard to think of any American child actors who were able to maintain a film career into adulthood as well as Léaud did. Mickey Rooney? Dean Stockwell? Who else?) Having Truffaut as a mentor certainly helped, but Léaud had an unmistakable gift. He is on screen for virtually all of the 99-minute run time, and provides a gallery of memorable moments: Antoine in the amusement-park centrifuge, Antoine in the police lockup, Antoine on the run -- in cinematographer Henri Decaë's brilliant long tracking shot. And my personal favorite moment: when the psychologist asks Antoine if he's ever had sex. Léaud responds with a beautiful mixture of surprise, amusement, and embarrassment. It's so genuine a response that I have to think it was improvised, that Truffaut surprised Léaud with the question. But even so, Léaud never drops character in his response. This praise of Léaud is not to undervalue the magnificent supporting cast, or the haunting score by Jean Constantin. It's a film in which everything works.

Antoine and Colette (François Truffaut, 1962)

Antoine Doinel: Jean-Pierre Léaud

Colette: Marie-France Pisier

Colette's Mother: Rosy Varte

Colette's Stepfather: François Darbon

René: Patrick Auffay

Albert Tazzi: Jean-François Adam

Director: François Truffaut

Screenplay: François Truffaut

Cinematography: Raul Coutard

Music: Georges Delerue

Four years after he made The 400 Blows, Truffaut was asked to contribute to an anthology of short films by directors from various countries to be called Love at Twenty. As he had with the first film, Truffaut drew on his own experience, an infatuation with a girl he had met at the Cinémathèque Française. And since Léaud was available -- he had worked with Julien Duvivier on Boulevard (1960) after completing The 400 Blows -- it made sense for him to play Antoine Doinel again. A narrator tells us that Antoine had been sent to another reform school after escaping from the first, and that this time he had responded well to a psychologist: After leaving school, he has found a job working for the Phillips record company and is living on his own. Then he sees a pretty young woman at a concert of music by Berlioz and falls for her. Colette is not much interested in him, but she is evidently flattered by his advances. Her parents like Antoine and encourage him so much that he rents a room across the street from them. (Truffaut had done the same thing during his crush.) But one evening when he comes to dinner at their apartment, a man named Albert calls on Colette and she leaves Antoine watching TV with her parents. It's a droll little film, scarcely more than an anecdote, and the stable, lovestruck Antoine doesn't seem much like either the rebellious Antoine of the first film or the more scattered Antoine of the later ones in the cycle.

Stolen Kisses (François Truffaut, 1968)

Antoine Doinel: Jean-Pierre Léaud

Christine Darbon: Claude Jade

Georges Tabard: Michael Lonsdale

Fabienne Tabard: Delphine Seyrig

M. Blady: Michael Lonsdale

Mme. Darbon: Claire Duhamel

Lucien Darbon: Daniel Ceccaldi

Director: François Truffaut

Screenplay: François Truffaut, Claude de Givray, Bernard Revon

Cinematography: Denys Clerval

Music: Antoine Duhamel

The Antoine of Stolen Kisses is in his 20s, but has reverted to the more haphazard ways of his adolescence: He has been kicked out of the army, and now relies on a series of odd jobs to get by. But he has also renewed acquaintance with a young woman he met before going into the army, Christine Darbon. Like Colette's parents, hers are quite taken with Antoine, and they help him get a job as a night clerk in a hotel. He gets fired from that job after helping a private detective who is spying on an adulterous couple, but the detective helps Antoine get a job with his agency. While working for the detective agency, he has to pose as a clerk in a shoe store, and winds up in a liaison with the store owner's wife, Fabienne. When that ends badly, he becomes a TV repairman, which brings him back to Christine, with whom he winds up in bed after trying to fix her TV. At the film's end, a strange man who has been following Christine comes up to her and Antoine in the park and declares his love for her. She says he must be crazy, and Antoine, who perhaps recognizes his earlier infatuation with Colette in the man's obsession, murmurs, "He must be." Stolen Kisses is the loosest, funniest entry in the cycle, though it was made at a time when Truffaut was politically preoccupied: The film opens with a shot of the shuttered gates of the Cinémathèque Française, which was shut down in a conflict between its director, Henri Langlois, and culture minister André Malraux. This caused an uproar involving many of the directors of the French New Wave. Some of Antoine's anarchic approach to life may have been inspired by the rebelliousness toward the establishment prevalent in the film community. But it's clear that the idea of a cycle of Antoine Doinel films has been brewing in Truffaut's mind: There is a cameo appearance by Marie-France Pisier as Colette and Jean-François Adam as Albert, now married and the parents of an infant.

Bed and Board (François Truffaut, 1970)

Antoine Doinel: Jean-Pierre Léaud

Christine Darbon Doinel: Claude Jade

Mme. Darbon: Claire Duhamel

Lucien Darbon: Daniel Ceccaldi

Kyoko: Hiroko Berghauer

Director: François Truffaut

Screenplay: François Truffaut, Claude de Givray, Bernard Revon

Cinematography: Néstor Almendros

Music: Antoine Duhamel

Antoine and Christine have married, and they have settled down in a small apartment. (There's some indication that it's paid for by her parents.) She gives violin lessons and he sells flowers -- carnations, which he dyes, using some environmentally questionable potions. But settling down isn't in Antoine's nature, and when Christine gets pregnant he looks for more lucrative work. He finds a curious sinecure in a company run by an American: Antoine maneuvers model ships by remote control through a mockup of a harbor. ("It gives me time to think," he says.) One day, a Japanese businessman comes to see the demonstration, accompanied by a pretty translator named Kyoko (Hiroko Berghauer), and Antoine is soon involved in an affair with her. Naturally, this precipitates a breakup, though by film's end they have seemingly reconciled. Still, it's obvious that the marriage is not destined to be permanent. They can't even agree on a name for their son: She wants him to be called Ghislain, and he wants to call him Alphonse. Antoine wins out by a trick: He's the one who goes to the registry office to legalize the boy's name. Antoine also spends time writing a novel about his boyhood, to which Christine objects: "I don't like this business of writing about your childhood, dragging your parents through the mud. I don't know much but I do know one thing: If you use art to settle accounts, it's no longer art." Truffaut had his own regrets about the portrait of his parents in The 400 Blows. Less farcical than Stolen Kisses, Bed and Board still has a strong vein of comedy tinged with melancholy.

Love on the Run (François Truffaut, 1979)

Antoine Doinel: Jean-Pierre Léaud

Colette Tazzi: Marie-France Pisier

Christine Doinel: Claude Jade

Liliane: Dani

Sabine Barnerias: Dorothée

Xavier Barnerias: Daniel Mesguich

M. Lucien: Julien Bertheau

Director: François Truffaut

Screenplay: François Truffaut, Marie-France Pisier, Jean Aurel, Suzanne Schiffman

Cinematography: Néstor Almendros

Music: Georges Delerue

Truffaut admitted that he wasn't happy with the final film in the cycle. It's a bit too heavily reliant on flashback clips from the four earlier films, and if it's intended to show that Antoine has finally stabilized now that he's in his 30s and divorced from Christine, it doesn't quite make the case. He has a new girlfriend, Sabine, his novel has been published several years earlier, and he works as a proofreader for a printing house. He's on friendly terms with Christine, and agrees to take their son, Alphonse, to the train station when the boy leaves for a summer music camp. At the station, he runs into Colette, now a defense lawyer, who is on her way to confer with a client -- a man who has murdered his 3-year-old boy. Perhaps a little too coincidentally, Colette is involved with Sabine's brother, Xavier, and having encountered Antoine before, she has bought a copy of his novel to read on the train. Antoine impulsively boards the train, and sets up a meeting with Colette in the dining car, after which she invites him back to her compartment. All of this sets up a series of revelations: Colette's marriage to Albert broke up after their small daughter was killed by a car. She claims that she supplements her small income as a lawyer by prostituting herself with men she meets on trains. Antoine finally made peace with his mother after her death when he met her old lover, M. Lucien, who persuaded him to visit his mother's grave. (There is a flashback to the scene in The 400 Blows when Antoine, playing hooky, sees his mother kissing a strange man on the street.) Antoine became infatuated with Sabine after hearing a man in a phone booth arguing with a woman on the other end of the line and then tearing up her photograph. Antoine picked up the pieces from the floor, put them together, and after some sleuthing, discovered the woman was Sabine. His marriage to Christine finally broke up after he slept with her friend Liliane, who he previously had thought was having a lesbian relationship with Christine. And so on. The result of all the flashbacks and revelations is not to round out the Antoine Doinel saga, but to make Love on the Run feel over-contrived. Marie-France Pisier, incidentally, contributed to the screenplay, which is mostly by Truffaut.

|

| Jean-Pierre Léaud in The 400 Blows |

Julien Doinel: Albert Rémy

Gilberte Doinel: Claire Maurier

René Bigey: Patrick Auffay

M. Bigey: Georges Flamant

Director: François Truffaut

Screenplay: François Truffaut, Marcel Moussy

Cinematography: Henri Decaë

Music: Jean Constantin

One of the unquestioned great movies, and one of the greatest feature-film directing debuts, The 400 Blows would still resonate with film-lovers even if François Truffaut hadn't gone on to create four sequels tracking the life and loves of his protagonist, Antoine Doinel (Jean-Pierre Léaud). There are, in fact, those who think that the last we should have seen of Antoine was the haunting freeze-frame at the end of the film. But Antoine continued to grow up on screen, and perhaps more remarkably, so did Léaud, carving out his own career after his debut as a 13-year-old. (It's hard to think of any American child actors who were able to maintain a film career into adulthood as well as Léaud did. Mickey Rooney? Dean Stockwell? Who else?) Having Truffaut as a mentor certainly helped, but Léaud had an unmistakable gift. He is on screen for virtually all of the 99-minute run time, and provides a gallery of memorable moments: Antoine in the amusement-park centrifuge, Antoine in the police lockup, Antoine on the run -- in cinematographer Henri Decaë's brilliant long tracking shot. And my personal favorite moment: when the psychologist asks Antoine if he's ever had sex. Léaud responds with a beautiful mixture of surprise, amusement, and embarrassment. It's so genuine a response that I have to think it was improvised, that Truffaut surprised Léaud with the question. But even so, Léaud never drops character in his response. This praise of Léaud is not to undervalue the magnificent supporting cast, or the haunting score by Jean Constantin. It's a film in which everything works.

Antoine and Colette (François Truffaut, 1962)

|

| Jean-Pierre Léaud and Marie-France Pisier in Antoine and Colette |

Colette: Marie-France Pisier

Colette's Mother: Rosy Varte

Colette's Stepfather: François Darbon

René: Patrick Auffay

Albert Tazzi: Jean-François Adam

Director: François Truffaut

Screenplay: François Truffaut

Cinematography: Raul Coutard

Music: Georges Delerue

Four years after he made The 400 Blows, Truffaut was asked to contribute to an anthology of short films by directors from various countries to be called Love at Twenty. As he had with the first film, Truffaut drew on his own experience, an infatuation with a girl he had met at the Cinémathèque Française. And since Léaud was available -- he had worked with Julien Duvivier on Boulevard (1960) after completing The 400 Blows -- it made sense for him to play Antoine Doinel again. A narrator tells us that Antoine had been sent to another reform school after escaping from the first, and that this time he had responded well to a psychologist: After leaving school, he has found a job working for the Phillips record company and is living on his own. Then he sees a pretty young woman at a concert of music by Berlioz and falls for her. Colette is not much interested in him, but she is evidently flattered by his advances. Her parents like Antoine and encourage him so much that he rents a room across the street from them. (Truffaut had done the same thing during his crush.) But one evening when he comes to dinner at their apartment, a man named Albert calls on Colette and she leaves Antoine watching TV with her parents. It's a droll little film, scarcely more than an anecdote, and the stable, lovestruck Antoine doesn't seem much like either the rebellious Antoine of the first film or the more scattered Antoine of the later ones in the cycle.

Stolen Kisses (François Truffaut, 1968)

|

| Jean-Pierre Léaud in Stolen Kisses |

Christine Darbon: Claude Jade

Georges Tabard: Michael Lonsdale

Fabienne Tabard: Delphine Seyrig

M. Blady: Michael Lonsdale

Mme. Darbon: Claire Duhamel

Lucien Darbon: Daniel Ceccaldi

Director: François Truffaut

Screenplay: François Truffaut, Claude de Givray, Bernard Revon

Cinematography: Denys Clerval

Music: Antoine Duhamel

Bed and Board (François Truffaut, 1970)

|

| Claude Jade and Jean-Pierre Léaud in Bed and Board |

Christine Darbon Doinel: Claude Jade

Mme. Darbon: Claire Duhamel

Lucien Darbon: Daniel Ceccaldi

Kyoko: Hiroko Berghauer

Director: François Truffaut

Screenplay: François Truffaut, Claude de Givray, Bernard Revon

Cinematography: Néstor Almendros

Music: Antoine Duhamel

Antoine and Christine have married, and they have settled down in a small apartment. (There's some indication that it's paid for by her parents.) She gives violin lessons and he sells flowers -- carnations, which he dyes, using some environmentally questionable potions. But settling down isn't in Antoine's nature, and when Christine gets pregnant he looks for more lucrative work. He finds a curious sinecure in a company run by an American: Antoine maneuvers model ships by remote control through a mockup of a harbor. ("It gives me time to think," he says.) One day, a Japanese businessman comes to see the demonstration, accompanied by a pretty translator named Kyoko (Hiroko Berghauer), and Antoine is soon involved in an affair with her. Naturally, this precipitates a breakup, though by film's end they have seemingly reconciled. Still, it's obvious that the marriage is not destined to be permanent. They can't even agree on a name for their son: She wants him to be called Ghislain, and he wants to call him Alphonse. Antoine wins out by a trick: He's the one who goes to the registry office to legalize the boy's name. Antoine also spends time writing a novel about his boyhood, to which Christine objects: "I don't like this business of writing about your childhood, dragging your parents through the mud. I don't know much but I do know one thing: If you use art to settle accounts, it's no longer art." Truffaut had his own regrets about the portrait of his parents in The 400 Blows. Less farcical than Stolen Kisses, Bed and Board still has a strong vein of comedy tinged with melancholy.

Love on the Run (François Truffaut, 1979)

|

| Claude Jade and Jean-Pierre Léaud in Love on the Run |

Colette Tazzi: Marie-France Pisier

Christine Doinel: Claude Jade

Liliane: Dani

Sabine Barnerias: Dorothée

Xavier Barnerias: Daniel Mesguich

M. Lucien: Julien Bertheau

Director: François Truffaut

Screenplay: François Truffaut, Marie-France Pisier, Jean Aurel, Suzanne Schiffman

Cinematography: Néstor Almendros

Music: Georges Delerue

Truffaut admitted that he wasn't happy with the final film in the cycle. It's a bit too heavily reliant on flashback clips from the four earlier films, and if it's intended to show that Antoine has finally stabilized now that he's in his 30s and divorced from Christine, it doesn't quite make the case. He has a new girlfriend, Sabine, his novel has been published several years earlier, and he works as a proofreader for a printing house. He's on friendly terms with Christine, and agrees to take their son, Alphonse, to the train station when the boy leaves for a summer music camp. At the station, he runs into Colette, now a defense lawyer, who is on her way to confer with a client -- a man who has murdered his 3-year-old boy. Perhaps a little too coincidentally, Colette is involved with Sabine's brother, Xavier, and having encountered Antoine before, she has bought a copy of his novel to read on the train. Antoine impulsively boards the train, and sets up a meeting with Colette in the dining car, after which she invites him back to her compartment. All of this sets up a series of revelations: Colette's marriage to Albert broke up after their small daughter was killed by a car. She claims that she supplements her small income as a lawyer by prostituting herself with men she meets on trains. Antoine finally made peace with his mother after her death when he met her old lover, M. Lucien, who persuaded him to visit his mother's grave. (There is a flashback to the scene in The 400 Blows when Antoine, playing hooky, sees his mother kissing a strange man on the street.) Antoine became infatuated with Sabine after hearing a man in a phone booth arguing with a woman on the other end of the line and then tearing up her photograph. Antoine picked up the pieces from the floor, put them together, and after some sleuthing, discovered the woman was Sabine. His marriage to Christine finally broke up after he slept with her friend Liliane, who he previously had thought was having a lesbian relationship with Christine. And so on. The result of all the flashbacks and revelations is not to round out the Antoine Doinel saga, but to make Love on the Run feel over-contrived. Marie-France Pisier, incidentally, contributed to the screenplay, which is mostly by Truffaut.

Sunday, January 15, 2017

Blood Simple (Joel Coen and Ethan Coen, 1984)

So many of the Coen brothers' best films, like Miller's Crossing (1990), Fargo (1996), and No Country for Old Men (2007), are about plans that backfire, that it's no surprise their first feature, Blood Simple, has a plot that hinges on just that. When Texas bar owner Julian Marty (Dan Hedaya) discovers that his wife, Abby (Frances McDormand), is having an affair with one of his bartenders, Ray (John Getz), he hires a private detective, Visser (M. Emmet Walsh), who discovered the affair, to kill them. But Visser has other ideas: He finds Ray and Abby asleep in Ray's bed, takes a picture of them, and steals Abby's gun. Then he doctors the photograph to make it look like he has shot them to death, collects the reward from Marty, and then shoots Marty with Abby's gun to frame her for his murder. But wait, there's more! It involves the fact that Marty is not (yet) dead, that he kept a copy of the doctored photo in his safe when he paid off Visser, and that Visser accidentally left his cigarette lighter behind in Marty's office. And so on, as almost everyone gets what's coming to them. Blood Simple may be just a tad over-plotted, and there are a few things that seem too contrived -- Visser's carelessness with the lighter, for one. But on the whole, it's good nasty fun, with some solid performances. McDormand, in her first film role, is strikingly pretty, and manages a remarkable character transition from naïveté to resourcefulness. Walsh and Hedaya, two reliable character actors, make the most of their juicy roles. Cinematographer Barry Sonnenfeld and composer Carter Burwell, both making their feature film debuts, help craft the film's very effective noir atmosphere.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)