A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Tuesday, February 28, 2017

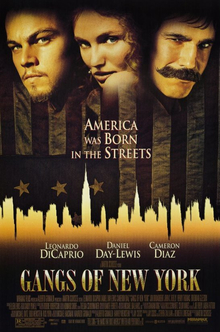

Gangs of New York (Martin Scorsese, 2002)

Gangs of New York is such a sprawling, unfocused movie that I can almost imagine the filmmakers throwing up their hands and sighing, "Well, at least we've got Daniel." Because Daniel Day-Lewis's performance as Bill "The Butcher" Cutting holds the film together whenever it tends to sink into the banality of its revenge plot or to wander off into the eddies of New York City history. A historical drama like Gangs of New York needs two things: a compelling central story and an audience that knows something about the history on which it's based. But for all their violence and their anticipation of problems that continue to manifest themselves in the United States, the Draft Riots of 1863 and the almost two decades of gang wars that led up to them are mostly textbook footnotes to most Americans. Director Martin Scorsese's determination to depict them led to the hiring of a formidable team of screenwriters -- Jay Cocks, who wrote the story, and Steven Zaillian and Kenneth Lonergan, who collaborated with Cocks on the screenplay. Unfortunately, the narrative thread that they came up with is tired. As a boy, Amsterdam Vallon saw his father, an Irish Catholic nicknamed "Priest" (Liam Neeson), cut down by Bill the Butcher in a huge battle between the Irish immigrant gang, the Dead Rabbits, and Bill's Protestant gang, the Natives. Sixteen years later Vallon (Leonardo DiCaprio) returns to the Five Points neighborhood determined to get revenge on Bill, who has managed to make peace with many of the old members of Vallon's father's gang and to become a power-player aligned with Tammany Hall and Boss Tweed (Jim Broadbent). Vallon is introduced to Bill's criminal enterprise by an old boyhood friend, Johnny (Henry Thomas), and he begins to fall under Bill's spell -- along with that of a pretty pickpocket, Jenny Everdeane (Cameron Diaz). But the relationship between Vallon and Jenny stirs the jealousy of Johnny, who is smitten with her, and he reveals to Bill that Vallon is the son of his old enemy, leading to a climactic showdown -- one that just happens to occur simultaneously with the Draft Riots. There's a lot of good stuff in Gangs of New York, including Michael Ballhaus's cinematography and Dante Ferretti's production design -- the sets were constructed at Cinecittà Studios in Rome. But the awkward attempt to merge the romantic revenge plot with the historical background shifts the focus away from what the film is supposedly about: racism, anti-immigrant nativism, political corruption, and exploitation of the poor. "You can always hire one half of the poor to kill the other half," Tweed says. Oddly (and sadly), Gangs of New York seems more relevant today than it did in 2002, when the country was recovering from the 9/11 attacks. Then, the Oscar-nominated anthem by U2, "The Hands That Built America," which concludes the film seemed to promise a spirit of unity, an affirmation that the country had overcome the antagonisms depicted in the movie. Today it has a far more ironic effect.

Monday, February 27, 2017

Y Tu Mamá También (Alfonso Cuarón, 2001)

|

| Gael García Bernal in Y Tu Mamá También |

Julio Zapata: Gael García Bernal

Tenoch Iturbide: Diego Luna

Narrator: Daniel Giménez Cacho

Silvia Allende de Iturbide: Diana Bracho

Diego "Saba" Madero: Andrés Almeida

Ana Morelos: Ana López Mercado

Manuel Huerta: Nathan Grinberg

Maria Eugenia Calles de Huerta: Verónica Langer

Cecilia Huerta: Maria Aura

Alejandro "Jano" Montes de Oca: Juan Carlos Remolina

Chuy: Silverio Palacios

Director: Alfonso Cuarón

Screenplay: Carlos Cuarón, Alfonso Cuarón

Cinematography: Emmanuel Lubezki

Production design: Marc Bedia, Miguel Ángel Álvarez

Film editing: Alfonso Cuarón, Alex Rodríguez

Alfonso Cuarón's Y Tu Mamá También is kept aloft for so long by wit and energy, and by the skills of its actors, director, and cinematographer, that it's a disappointment to consider the way it deflates a little at the end. It is, on the whole, a brilliant transfiguration of several well-worn genres: the teen sex comedy, the road movie, the coming-of-age fable. Cuarón has credited Jean-Luc Godard's Masculin Féminin (1966) as a major inspiration, but I think it owes as much to François Truffaut's Jules and Jim (1962), not least in Daniel Giménez Cacho's superbly ironic voiceover narrator, who provides a larger context for the actions of the three main characters. It's the narrator, for instance, who tells us that the traffic jam that holds up our middle-class teenagers was caused by the death of a working man who tried to cross the freeway because otherwise he would have had to walk a mile and a half out of his way to use the only crossing bridge. Or that Chuy, the fisherman who befriends the trio when they finally reach the secluded beach, will lose his livelihood to developers and commercial fisheries and wind up as a janitor in an Acapulco hotel. Somehow, Cuarón manages to avoid heavy-handedness with these comments, injecting the necessary amount of serious social commentary into a story about two horny Mexico City teenagers and the older woman who goes in search of a beach called "Heaven's Mouth" with them. Even in the story, the subtext of social class in contemporary Mexico keeps peeking through: There's a slight tension between the upper-middle-class Tenoch, whose father is a government official, and the lower-middle-class Julio that's suggestive of Tenoch's sense of privilege. Similarly, Luisa, who was trained as a dental technician, confesses to a sense of inferiority to her husband, Jano, Tenoch's cousin, and his better-educated friends. The screenplay by Cuarón and his brother, Carlos, deserved the Oscar nomination it received for these attempts to provide a deep backstory for the characters. Even so, the film owes much to the obvious rapport between Luna and García Bernal, and to the steady centering influence of Verdú, all of whom participated in rehearsals that were often improvisatory embroidering on the Cuaróns's screenplay. Cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, who would go on to receive three consecutive Oscars for much showier work on Cuarón's Gravity (2013) and on Alejandro Iñárritu's Birdman (2104) and The Revenant (2015), here maintains a strictly documentary style of camerawork, though often with the subtle use of long takes and wide-angle lenses. As I said, I think the film deflates a bit at the end with the revelation of Luisa's death: It seems an unnecessary attempt to moralize, to provide a motive -- knowing that she has terminal cancer -- for her running away and having sex with the boys, turning it into only a final fling. Would we think less of Luisa if she were simply asserting her right to be as pleasure-driven as her philandering husband? Were the Cuaróns attempting to obviate slut-shaming by giving Luisa cancer? I hope not, because the film shows such intelligence and sensitivity otherwise.

Sunday, February 26, 2017

Tomorrow (Joseph Anthony, 1972)

|

| Olga Bellin and Robert Duvall in Tomorrow |

Saturday, February 25, 2017

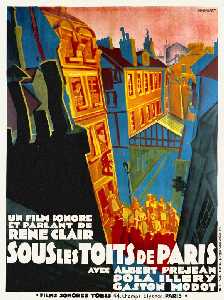

Under the Roofs of Paris (René Clair, 1930)

Under the Roofs of Paris, writer-director René Clair's sometimes shaky but often charming bridge between silent films and talkies, begins with cinematographer Georges Périnal's lovely crane shot that slowly descends from the rooftops of Paris -- actually the rooftops of art director Lazare Meerson's elaborate and ingenious set -- to the street where song-plugger Albert (Albert Préjean) is conducting a singalong of "Sous les Toits de Paris," the film's French title song, trying to sell copies of the sheet music. As the camera pans around the crowd, we meet several more characters prominent in the film: the thief Émile (Bill Bocket), who is carefully lifting small valuables from women's purses; the dandyish gangster Fred (Gaston Modot); and a pretty young Romanian woman, Pola (Pola Illéry), who becomes a target for both Émile's thievery and Fred and Albert's attentions. Albert is a success at selling the song, as we see in a vertical pan up the façade of an apartment building, from each window of which comes the sound of someone singing it. This beautiful shot demonstrates how quickly Clair, a reluctant convert, caught on to the innovations possible in sound films. It may have influenced Rouben Mamoulian's brilliant montage in Love Me Tonight (1932), which tracks from Maurice Chevalier singing "Isn't It Romantic?" in his Paris tailor shop as the song spreads across country to Jeanette MacDonald singing it in her château. But Clair also displays some of the uncertainty of silent filmmakers in his dialogue scenes, which have the curious sluggish pace found in early talkies whose directors haven't figured out the rhythm of scenes that aren't interrupted by intertitles. In fact, Clair uses synchronized dialogue sparingly: There are a lot of scenes in which we don't hear what characters are saying, sometimes because the music in the bar where they're talking is too loud, and sometimes because we're viewing them through windows and glass doors. Much of the film uses familiar silent storytelling techniques -- to good effect. The story deals with Albert's ill-fated love for Pola, which develops when Fred steals her house key, making it necessary for her to spend the night (chastely and comically) in Albert's apartment. But then Albert is caught with some of Émile's loot -- the thief has stashed it in Albert's room -- and sent to jail. During his absence, Pola falls for Albert's friend Louis (Edmond T. Gréville), leaving things to be resolved at the film's bittersweet end, when the camera tracks away from Albert plugging a new song back up to the rooftops. The film plays on a characteristic fascination with Parisian lower-class life that includes slumming well-dressed upper-class types dropping in on the dives to see how the other half lives -- a motif that recurs in other French films set in the Paris underworld, like Jacques Becker's Casque d'Or (1952).

Friday, February 24, 2017

Brute Force (Jules Dassin, 1947)

Surprisingly violent for a film made under the Production Code, Brute Force gives us a prison-break story in which we root for the prisoners, but it still comes down heavily on the crime-does-not-pay moral: "Nobody escapes," says one of the movie's few survivors to the camera at the end. "Nobody ever really escapes." Under Jules Dassin's direction, Richard Brooks's screenplay tries to have it both ways: The cons are heroic and the guards are villainous, but law and order must prevail. The easy way out of this is to kill off both the heroes and the villains. The chief hero is Joe Collins, played by Burt Lancaster with his usual handsomely bullish intensity. The chief villain is the head guard, Capt. Munsey, played against type by Hume Cronyn. The imbalance between the two is exhibited early in the film when Munsey tries to dress down Collins but is confronted with a massive Lancastrian cold shoulder. But Munsey has guile on his side, along with ambition to supplant the weakling Warden Barnes (Roman Bohnen), who is under political pressure to toughen up enforcement in the prison, from which reports of unrest among the inmates have been emerging. Dassin tells us all we need to know about Munsey when we see him in his office, which has little homoerotic touches in its decor like a picture of a male torso, along with a large Hitlerian photograph of Munsey himself. While beating a prisoner with a rubber hose to elicit information about a planned prison break, Munsey turns up the volume on the Wagner he is playing on the phonograph. Not that the cons are any less gentle: To punish a prisoner who collaborated with the guards, they force him into the machine that stamps out license plates, and during the climactic prison break, a stoolie is strapped to the front of a mine car and shoved out into the gunfire from the guards. The film never really lightens things up, though there are some flashback scenes involving tender moments between some of the prisoners and what the credits bill as "the women on the 'outside,'" including Ann Blyth as Collins's cancer-stricken wife. There are some good performances from Charles Bickford as the con who edits the prison newspaper and joins the escape plan after he learns that his expected parole has been put on indefinite hold, and Art Smith as the prison's cynical, alcoholic doctor, along with solid support from Sam Levene, Jeff Corey, Howard Duff, and a horde of well-chosen ugly-mug extras.

Thursday, February 23, 2017

Eat Drink Man Woman (Ang Lee, 1994)

|

| Yu-Wen Wang, Chien-Lien Wu, and Kuei-Mei Yang in Eat Drink Man Woman |

Wednesday, February 22, 2017

The Grapes of Wrath (John Ford, 1940)

Did Tom Joad's descendants vote for Donald Trump? Do Marfa Lapkina's support Vladmir Putin? John Ford's The Grapes of Wrath begins with a tractor pushing people from the land they've worked, while The Old and the New (Sergei Eisenstein and Grigori Aleksandrov, 1929) ends with a tractor helping people harvest their crops. It's just coincidence that I watched two movies about oppressed farm laborers on consecutive nights, but the juxtaposition set me thinking about the ways in which movies lie to us about matters of politics, history, and social justice (among other things). In both cases, a core of truth was pushed through filters: in Eisenstein's, that of the Soviet state, in Ford's that of a Hollywood studio. So in the case of The Old and the New we get a fable about the wonders of collectivism and technology, whereas in The Grapes of Wrath we get a feel-good affirmation of the myth that "we're the people" and that we'll be there "wherever there's a fight, so hungry people can eat." Both films are good, but neither, despite many claims especially for The Grapes of Wrath, is great, largely because their messages overwhelm their medium. Movies are greatest when they immerse us in people's lives, thoughts, and emotions, not when they preach at us about them. It's what makes William Faulkner's As I Lay Dying a greater novel than John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath. Both are superficially about the odysseys of two poor white families, but Faulkner lets us live in and with the Bundrens while Steinbeck turns the Joads into illustrated sociology. Ford won the second of his record-setting four Oscars for best director for this film, and it displays some of his strengths: direct, unaffected storytelling and a feeling for people and the way they can be tied to the land. It has some masterly cinematography by Gregg Toland and a documentary-like realism in the use of settings along Route 66. The actors, including such Ford stock-company players as John Carradine, John Qualen, and Ward Bond, never let Hollywood gloss show through their rags and stubble -- although I think the kids are a little too clean. Nunnally Johnson's screenplay mutes Steinbeck's determination to go for the symbolic at every opportunity -- we are spared, probably thanks for once to the censors, the novel's ending, in which Rosasharn breastfeeds an old man. But there's a sort of slackness to the film, a feeling that the kind of exuberance of which Ford was capable in movies like Stagecoach (1939) and The Searchers (1956) has been smothered under producer Darryl F. Zanuck's need to make a Big Important Film. I like Henry Fonda in the movie, but I don't think he's ever allowed to turn Tom Joad into a real character; it's as if he spends the whole movie just hanging around waiting to give his big farewell speech to Ma (Jane Darwell, whose own film-concluding speech won her an Oscar).

Tuesday, February 21, 2017

The Old and the New (Sergei Eisenstein and Grigori Aleksandrov, 1929)

Sergei Eisenstein's last silent film almost deserves the old joke that you can always tell a Soviet film because the hero is a tractor. The Old and the New (sometimes called Old and New; the Russian language has no definite or indefinite articles) does conclude with a kind of ballet of tractors, but its hero is human: Marfa Lapkina, an actual Russian peasant who essentially plays herself in a story about the efforts to organize a kolkhoz, a collective farm. We first see Marfa struggling to survive as a farmer who doesn't even have a horse. Reduced to begging, she goes to the fat, greasy kulaks in her neighborhood, who reject her pleas for help. But a revolutionary organizer arrives in the village to set up a collective and introduce the locals to farm machinery. The rest of the film depicts Marfa's rise to leadership of the collective, battling the resistance of stick-in-the-muds, kulaks who poison the collective's bull, and bureaucrats who drag their feet on providing the collective with a tractor. The film was begun in 1927 under the title The General Line, but Eisenstein's work on it was interrupted so he could finish October (Ten Days That Shook the World), a celebration of the tenth anniversary of the Bolshevik revolution. Meanwhile, Leon Trotsky, whose ideas about collective agriculture were the original impetus for the film, fell from power -- a foreshadowing not only of the difficulties Eisenstein was to have dealing with Soviet ideology as Stalin consolidated his power, but also of the troubles ahead for Russian farmers in the 1930s. The film was taken out of Eisenstein's hands and re-edited, but the restored version we have today is visually fascinating: The opening scenes of suffering Russian peasants, strikingly filmed by Eduard Tisse, bring to mind the work of Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange in documenting American farmers in the South and the Dust Bowl during the Depression. There are several bravura montages, some of which are used for a comic effect we don't usually expect from Eisenstein, such as the "wedding scene" in which the bride turns out to be the collective's cow and the groom the bull, and the demonstration of a new milk separator that builds to an orgasmic release of cream from the machine's lovingly filmed spigots. But the propaganda is also thick and heavy in the depiction of kulaks and bureaucrats, and especially in the treatment of the Orthodox church in a scene in which an ecclesiastical procession goes out to pray for rain to end the drought. The images of the sweaty clergy and congregants carrying icons and prostrating themselves in supplication are intercut with images of bleating sheep. Eisenstein left the Soviet Union, accompanied by Tisse and his co-director Girgori Aleksandrov, in 1928; after a disastrous attempt to work in the United States and Mexico, he was persuaded to return to Russia in 1932 but didn't complete another film until Alexander Nevsky in 1938.

Monday, February 20, 2017

Svengali (Archie Mayo, 1931)

|

| Marian Marsh, Bramwell Fletcher, and John Barrymore in Svengali |

Trilby O'Farrell: Marian Marsh

The Laird: Donald Crisp

Billee: Bramwell Fletcher

Madame Honori: Carmel Myers

Gecko: Luis Alberni

Monsieur Taffy: Lumsden Hare

Bonelli: Paul Porcasi

Director: Archie Mayo

Screenplay: J. Grubb Alexander

Based on a novel by George L. Du Maurier

Cinematography: Barney McGill

Art direction: Anton Grot

Film editing: William Holmes

Music: David Mendoza

George Du Maurier's 1894 novel was called Trilby, as were many of the stage adaptations and early silent film versions. But if you cast John Barrymore as the sinister hypnotist, you almost have to call your film Svengali. It's one of Barrymore's juiciest movie performances, but it surprisingly didn't earn him an Oscar nomination -- an honor he never received. To add to the irony, the best actor Oscar that year went to his brother Lionel for A Free Soul (Clarence Brown, 1931), and one of the actors who did receive a nomination was Fredric March for playing Tony Cavendish, an obvious caricature of John Barrymore, in The Royal Family of Broadway (George Cukor and Cyril Gardner, 1930). Though Barrymore's Svengali doesn't particularly deserve an award, it's the best thing about the film aside from the sets by Anton Grot that were influenced by German expressionism and did earn Grot a nomination, as did cinematographer Barney McGill's filming of them. Like many early talkies, Svengali is slackly paced, as if director Archie Mayo, who learned his craft in the silent era, was still slowing things down so title cards could be placed at the appropriate intervals. It also has some problems of tone: Svengali is not quite the sinister monster you expect him to be from his reputation as an archetype of masterful control. In the beginning he's the butt of horseplay from some of his fellow Paris bohemians, the painters known as The Laird and Taffy, who decide he doesn't bathe often enough and dump him into a bathtub. We know his potential for evil after he causes Madame Honori to commit suicide, but even her character is played for comedy before her untimely end. In this adaptation, by J. Grubb Alexander, the plot revolves around Svengali's manipulation of Trilby, an artist's model whose potential as a singer -- even though she can't quite carry a tune -- he deduces from the shape of her mouth. He uses his hypnotic powers to turn her into a diva, though the one performance we see from her, a bit of the Mad Scene from Lucia di Lammermoor, doesn't merit the ovation it receives -- perhaps he hypnotized the audience, too. But control of Trilby comes at a cost: Svengali's health begins to decline, and Trilby's career along with it, until at the end they both die as she performs in a nightclub in Cairo, second-billed to a troupe of belly-dancers. Only the lovestruck young artist known as "Little Billee," who has devoted his life to tracking Trilby in hopes of winning her back, is there to witness her end. Thanks to Barrymore, and some good support from character actors like Luis Alberni, who plays Svengali's assistant with the improbable name Gecko, Svengali is never unwatchable, and it mostly avoids the antisemitic notes that many have observed in the character, who is said to have mysterious origins, perhaps in Poland, in the novel and its adaptations.

Sunday, February 19, 2017

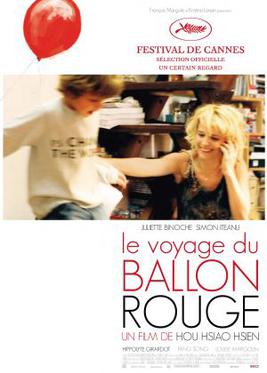

Flight of the Red Balloon (Hou Hsiao-Hsien, 2007)

The Red Balloon (Albert Lamorisse, 1956) is a short film that won the Oscar for best original screenplay, even though it's only a little over half an hour long and has only a few lines of spoken dialogue. In it, a boy (writer-director Lamorisse's young son, Pascal) on his way to school finds a large red balloon that has become caught in a lamppost. He soon discovers that he can't take the balloon with him on a bus or into his school, but the balloon is waiting for him after classes. He's also forbidden to bring the balloon into his home, but it floats up to his bedroom window and he lets it in. Over the next couple of days, the balloon tags along, sometimes getting the boy into trouble, until it's finally punctured by a rock fired from another boy's slingshot and slowly dies. Whereupon balloons from all over Paris flock to the boy, who gathers them and floats away over the rooftops. It's a small charmer, with ravishing views of 1950s Paris by cinematographer Edmond Séchan. The balloon becomes emblematic of childhood innocence in conflict with the daily grind of adulthood, which is why I think it still strikes a chord with audiences and, in the case of Taiwanese director Hou Hsiao-Hsien, inspired an hommage: The Voyage of the Red Balloon. Hou's film, which he co-wrote with François Margolin, is nearly four times the length of Lamorisse's and doesn't have such a neatly symbolic resolution. In it, a boy, Simon (Simon Iteanu), lives with his mother, Suzanne (Juliette Binoche), in a cramped Paris apartment. Suzanne is a puppeteer -- a profession that links her with childhood -- who hires a Chinese film student, Song (Fang Song), as a part-time nanny for Simon. Song is working on her own homage to The Red Balloon, and we see bits of it as she poses Simon with a balloon and films it floating around the city. But much of Hou's film deals with the domestic turmoil that surrounds Simon as Suzanne, a divorcee, tries to cope with juggling career and household problems. She leases part of the building to Marc (Hippolyte Girardot), who has been stiffing her on the rent and tends to pop into her apartment at odd times to use her kitchen and leave it a mess. She is trying to evict him so she'll have a place for her daughter, who lives with Suzanne's ex-husband in Brussels, to stay when she comes to Paris in the summer. Simon patiently endures his mother's frazzled nerves and finds a companion in Song, who quietly manages to bring a little order into the household. By film's end, nothing is really resolved in their lives, but a red balloon peeps into the apartment windows and floats above the skylight over Simon's bed, as if childhood has persisted for the time being against all the assaults against it. It's a poetic, meditative kind of film that gains its strength from immersing us into the lives of others. It seems to me to stretch out a little longer than it should, but it features another terrific performance by Binoche.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)