A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Wednesday, May 3, 2017

X-Men: Apocalypse (Bryan Singer, 2016)

Oscar Isaac is one of my favorite actors. I loved his work in Inside Llewyn Davis (Joel and Ethan Coen, 2013), A Most Violent Year (J.C. Chandor, 2014), Ex Machina (Alex Garland, 2015), and on the HBO miniseries Show Me a Hero (2015). He even managed to stand out in all the whiz-bang and nostalgia of the latest Star Wars installment. But I sat through the entirety of X-Men: Apocalypse without realizing, until his name appeared in the credits, that he was the one beneath all the makeup and prosthetics as En Sabah Nur, aka Apocalypse. Which makes me wonder: Why bother? Casting an actor of such skill and versatility in a role that could have been played by anyone willing to sit through hours of applying and removing body paint, silicone, and foam latex seems to me a waste of valuable resources. But I guess the same thing could be said about the entire film if you ignore the return the producers got on their estimated $178 million investment. When a film this size feels routine, something has gone awry, and X-Men: Apocalypse is nothing if not routine. There are things I enjoyed about it, like the special effects when Quicksilver (Evan Peters) rescues almost everyone from the explosion that destroys the institute. The trick of seeing everything as Quicksilver sees it -- i.e., as time standing still while he moves at superspeed, dashing from room to room to haul occupants to safety -- is nicely done. And there are good performances from Peters, from James McAvoy as Charles Xavier, Michael Fassbender as Erik Lehnsherr, Jennifer Lawrence as Raven, Nicholas Hoult as Hank McCoy, and Kodi Smit-McPhee as Nightcrawler. I enjoyed seeing Sophie Turner (as the latest iteration of Jean Grey) in something other than Game of Thrones and Hugh Jackman in an unbilled (and extremely violent) cameo as Logan/Wolverine. But there's a kind of heartlessness and thoughtlessness about it, too often characteristic of the superhero blockbuster movie genre, that my experience amounted to a kind of déjà vu. I just hope Isaac got paid well.

Tuesday, May 2, 2017

L'Argent (Robert Bresson, 1983)

When does style become mannerism? And why is it that style is generally thought of as a good thing, and mannerism is often a pejorative? I found myself pondering these questions while watching Robert Bresson's last film, L'Argent. Bresson is one of the directors I most admire, so my first impulse is to admire L'Argent as a superb example of Bresson's austere style: his willingness to let the audience decide what's going on within the characters by restraining his actors' displays of emotion, the simplicity of his mise-en-scène, his use of ambient sound to do the job that other directors rely on musical scores to accomplish. He has a fascinating premise to explore in L'Argent, which he adapted from a story by Tolstoy: the horrible repercussions of the passing of a counterfeit bill by some schoolboys. They spend the bill in a photography shop, buying a picture frame mainly to get some real money in change. When the fake bill is discovered, the shop owner passes it off in payment to Yvon (Christian Patey), the young driver of a heating-oil delivery truck. When Yvon is arrested for passing counterfeit money, he identifies the clerk at the photography shop, Lucien (Vincent Risterucci), who gave him the money. But Lucien perjures himself, saying he had never seen Yvon before, so Yvon is convicted. Though he's given a suspended sentence, he loses the job that he needs to support his wife and small daughter. Unable to find work, he agrees to act as the getaway driver for an acquaintance who's robbing a bank, but is caught and thrown into prison. Life in prison does him no good, especially after he learns that his daughter has died of diphtheria and his wife has decided to start a new life. When he lashes out at a fellow inmate he is thrown into solitary. He attempts suicide, but survives and returns to prison where he finds that Lucien is also an inmate, having robbed the photography store and become rich through various forms of larceny. Embittered, Yvon serves out his term and is released, but he continues his descent into criminality, murdering the keepers of a small hotel and robbing them, and finally finding shelter with an elderly woman (Sylvie Van den Elsen), whom he also murders, along with her entire household. At the end, he confesses and is returned to prison. Bresson's dry, understated telling of this story gives it a kind of dreamlike matter-of-factness that a more florid and violent version couldn't achieve. But there are also moments when you become aware of the way Bresson is telling the story, moments in which, I think, style becomes mannerism, especially if you've seen enough Bresson films to recognize his particular way of dramatizing events. For example, there is one scene in which the camera focuses on a passageway in the Paris Métro: What we see for a long time (perhaps only seconds, but it feels longer given our natural impatience to want things to happen in a movie) are the foot of a stairway, the concrete floor and tiled walls, and the beginning of a passageway to the trains. Bresson holds on this empty space as we hear the train arrive and the doors open and people make their way toward the space, through it, and up the stairs past us. He stays on the space until people -- they are Lucien and two of his friends -- come down the stairs past us and enter the passage. We hear the train doors close and the train depart, and only then does Bresson cut to the platform and the train entering the tunnel. It's a moment of no real narrative importance, but Bresson's holding us there as it happens crafts a kind of suspense, a kind of anxiety of the quotidian that informs the entire film. The only problem I have with the scene is the way it sticks in my memory as an inflection of style. And remembering this moment at the expense of others more important to the theme and narrative of L'Argent makes me think of it as mannered. While it's still a fascinating and challenging film, Bresson's deadpan actors and his focus on emptiness lend themselves easily to caricature and parody, and I think he carries them too far in L'Argent, never finding the balance that make his masterworks -- Diary of a Country Priest (1951), A Man Escaped (1956), Au Hasard Balthazar (1966) -- such essential films.

Monday, May 1, 2017

Bridge of Spies (Steven Spielberg, 2015)

It goes without saying that Steven Spielberg is one of the great directors, with a seldom-equaled skill at visual storytelling and at building tension and suspense. But Spielberg tries too hard to make a statement in Bridge of Spies -- something about defending the Constitution -- when it could have been simply an engaging film about Cold War tensions. It also suffers from the wrong kind of star power: Tom Hanks has devolved from a terrific actor, skilled at both comedy and drama, into the movies' iconic Good Guy. Casting him as the lawyer James Donovan, forced to defend a Soviet spy, deprives the film of any ambiguity about Donovan's defense of Rudolf Abel (Mark Rylance). Hanks's Donovan can simply wrap himself in the Constitution and we're with him all the way, even as public opinion of the time turns against him. As a film actor Hanks has lost his dark side, so we know that whoever he plays will triumph. Imagine Bridge of Spies with Donovan played by George Clooney or Bradley Cooper, stars with just a touch of shadow in their personae, and you can see what I mean. Fortunately, the film is otherwise well-cast, including Rylance's Oscar-winning turn as Abel, as well as Scott Shepherd's impatient CIA man and Sebastian Koch's duplicitous East German lawyer, and the screenplay by Matt Charman and Joel and Ethan Coen manages a good deal of suspense. (Sometimes at the expense of historical accuracy: Donovan was never shot at in his home, as the film has it.) The Coen brothers were brought in to work on the first draft of Charman's screenplay, specifically on the section in which Donovan finds himself negotiating separately with the Soviets and the East Germans to engineer an exchange of Abel for imprisoned U2 pilot Francis Gary Powers (Austin Stowell) and an American student, Frederic Pryor (Will Rogers), who has been accidentally arrested in East Berlin. It's the best part of the movie, as Donovan wrangles not only with the conflicting egos and bureaucracies of the Soviet and East German officials but also with the CIA's insistence that only Powers need be included in the deal. Unfortunately, Spielberg doesn't know when his movie is over. Bridge of Spies should end with the exchange of spies at the bridge, but Spielberg keeps it running as Donovan boards the plane for home, returns to the arms of his family just as the news of his successful negotiation is breaking, gives his wife (Amy Ryan) the jar of marmalade he promised to bring her from London, witnesses her realization that he wasn't in London after all, and soon afterward rides to work on the bus where a woman who had previously frowned at him as a traitor now smiles at him as a hero after seeing his picture in the newspaper. All the while, Thomas Newman's score is telling us what we're supposed to feel. It's sheer sentimental anticlimax, of the sort that many critics decry in what are usually regarded as Spielberg's greatest films, Saving Private Ryan (1998) and Schindler's List (1993). (I happen to agree that the frame story of the aging Ryan's visit to the cemetery in Normandy is unnecessary, though I think the Yad Vashem sequence at the end of the latter film can be justified by the enormity of its subject matter.) Bridge of Spies is by no means a bad movie, but it would have been a lot better if Spielberg hadn't given in to his instinct for overemphasis.

Sunday, April 30, 2017

Il Posto (Ermanno Olmi, 1961)

|

| Loredana Detto and Sandro Panseri in Il Posto |

Domenico Cantoni: Sandro Panseri

Psychologist: Tullio Kezich

Domenico's Older Co-worker: Mara Revel

Director: Ermanno Olmi

Screenplay: Ermanno Olmi

Cinematography: Lamberto Caimi

Production design: Ettore Lombardi

Film editing: Carla Colombo

Music: Pier Emilio Bassi

Kafka was a realist. Anyone who has ever worked for a large, bureaucratic corporation knows this. Being pushed about, subjected to irrational rules and decrees, unable to do more in the face of injustice than simply duck and cover -- these are the facts of corporate life that echo throughout the stories of the former employee of the Workers Accident Insurance Institute in Prague. Ermanno Olmi's Il Posto (i.e. "the job") isn't really based on Kafka, though I suspect Olmi may have been familiar with his work, because the frustration that the film's young protagonist, Dominico Cantoni, runs up against has a striking resemblance to the arbitrary barriers that prevent Kafka's characters from making a break toward freedom. But Il Posto is also clearly under the influence of something Olmi certainly knew firsthand: Italian neorealism. Like Vittorio De Sica and Roberto Rossellini, Olmi works largely with non-professional actors in Il Posto -- on IMDb, Panseri has only two more credits and a note that he was a supermarket manager in Milan -- and the streets of Milan and its suburb of Meda are its principal setting, neither of them the beneficiary of any attempts at sprucing up and glamorizing. The human milieu of Il Posto is the office workers of the lower middle class, people who see a chance at lifetime employment with a big company as salvation from downward mobility. Domenico has left school to help support his family -- father, mother, and younger brother -- and the possibility of landing a job with the unnamed company looks like a godsend. So he rides the train into Milan and goes through a series of tests, including absurd physical and psychological exams obviously designed by someone with just enough knowledge to be a nuisance. On his lunch break, he meets a fellow job applicant, the pretty Antonietta (Loredana Detto became Olmi's wife two years later), and he's pleased to find, a few days later, that they've both been hired. Unfortunately, they have jobs in different parts of the company and their lunch hours don't mesh, so for the rest of the film they are unable to further their relationship. When they do manage to meet, Antonietta tells him about an employees' New Year's Eve party, which he attends only to find that she hasn't shown up. Though no clerical position is immediately available, Domenico is taken on as a messenger between departments, a job that mostly consists of sitting at a small table with his supervisor and waiting. Meanwhile, we meet some of the older employees, most of whom spend their days in the tiny office into which their desks have been crammed dozing, doing busywork, or getting chewed out for being late. Olmi takes a striking departure from Domenico's story to show us snippets of the after-hours lives of these employees, supplying a backstory that keeps them from just being caricatures. Then one of this group dies, and Domenico is promoted to his job. But when he arrives at the man's desk, it's being cleared out and another employee protests that this desk, at the front of the room, should go to someone with seniority. So when it's ready, there's a mad rush to claim it, leaving Domenico in the poorly lighted back of the room. The film ends with a closeup on his face as a mimeograph machine clacks away. He says and does nothing, but when we reflect that the young man has just seen what's involved in attaining a position that will last for the rest of his life, we can imagine his feelings. Il Posto is a small film but a brilliant one that brings to mind more celebrated films about corporate life, such as The Crowd (King Vidor, 1928) and The Apartment (Billy Wilder, 1960), in the company of which it stands up well.

Saturday, April 29, 2017

Lost Highway (David Lynch, 1997)

|

| Patricia Arquette and Bill Pullman in Lost Highway |

Friday, April 28, 2017

Children of Nagasaki (Keisuke Kinoshita, 1983)

|

| Yukiyo Toake* and Go Kato* in Children of Nagasaki |

Maria Midori Nagai*: Yukiyo Toake

Grandmother: Chikage Iwashima

Makoto*: Masatomo Nakabayashi

Director: Keisuke Kinoshita

Screenplay: Keisuke Kinoshita, Taichi Yamada, Kazuo Yoshida

Based on writings by Takashi Nadai

Cinematography: Kozo Okazaki

Music: Chuji Kinoshita

I've seen only three films by Keisuke Kinoshita, but it's clear from those three that the director was haunted throughout his life by the tragedy that militarism inflicted on his country. Morning for the Osone Family (1946) is a depiction of what one family, divided by its attitudes toward the war, went through during its waning years. Twenty-Four Eyes (1954) is a sentimental yet oddly powerful anti-war film that takes place in a pastoral setting virtually untouched by bombing raids, yet deeply wounded by the conflict just over the horizon. Children of Nagasaki was one of his last films, and also one of his least known in the West -- it has no reviews on Rotten Tomatoes, a link to only one review on IMDb, and no entry at all in Wikipedia. But of the three it's the only one that directly confronts the physical horror of the war. It's essentially a biopic of Takashi Nagai, a physician who survived the nuclear explosion in Nagasaki and devoted himself to writing about the event and its aftermath, using his training as a radiologist to document the effects of radiation. Most of Nagai's writing was censored by the occupation authorities and not published until after his death in 1951 from leukemia, with which he had been diagnosed before the bomb fell on Nagasaki. In the film, Nagai is at work when the bomb is dropped, killing his wife. His two children are in the country with their grandmother, and with her help he goes about the task of rebuilding their home and their lives. The film, which begins with scenes from the visit to Nagasaki by Pope John Paul II in 1981, is suffused with Nagai's Roman Catholic faith, and while it's not clear if Kinoshita shared Nagai's faith -- the director is buried in a Buddhist cemetery -- he treats it with deep respect, even reverence. Children of Nagasaki is an uneven film, a little too heavily didactic, as the literally preachy use of the pope to open the film suggests. Three-quarters of the way in, Kinoshita suddenly and clumsily switches to a narrator, Nagai's grown son, reflecting on the life of his father. But he makes one striking choice: not to depict the horrors inflicted on the people of Nagasaki by the bomb at the point in the narrative when they occur, but instead to show them at the end of the film in a flashback, reinforcing the point that such a story can't really have a happy ending.

*These identifications are unconfirmed. IMDb lists only cast members and not the names of the roles they play. I've resorted to guesswork based on other sources in making the identifications. Corrections are welcome.

Thursday, April 27, 2017

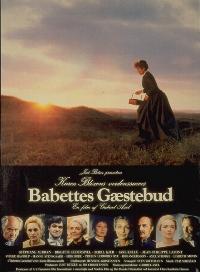

Babette's Feast (Gabriel Axel, 1987)

I had an odd experience this morning when I sat down to write this blog entry: I couldn't remember what film I watched last night. Ordinarily I'd ascribe this memory lapse to a "senior moment," but once I remembered that the film was Gabriel Axel's Babette's Feast, I thought I knew what caused it. This is what I call a "mood movie," one that, like some pieces of music, is designed -- or perhaps better, destined -- to put you into a certain emotional state. In the case of Babette's Feast, it's a kind of sweet melancholy, a state so ephemeral that almost anything can sweep it away -- as my experience of Babette's Feast was wiped away when I watched Survivor and Marvel's Agents of Shield, not exactly sweetly melancholic shows, immediately afterward on TV. This is not meant as a knock on Gabriel Axel's film, the screenplay for which he adapted from a story by Karin Blixen (aka Isak Dinesen). After all, it won the Oscar for best foreign language film, beating out among other contenders Louis Malle's Au Revoir les Enfants. It does what it does extraordinarily well, which is to tell a story, evoke a particular time and place, and present us with memorable characters. It centers on two sisters, Filippa (Bodil Kjer) and Martine (Birgitte Federspiel), who live in a small Danish village where they tend to the aging congregation of a small, austere sect which their father gathered together many years ago. A kindly man, he nevertheless dominated their lives to the extent that suitors were discouraged from marrying them. One of Filippa's suitors was an aging French operatic baritone, Achille Papin (Jean-Philippe Lafont), who was traveling through the village and happened to hear her singing in the church. Smitten with both her beauty and her voice, he offered to give her singing lessons, but when he proposed to take her to Paris and make her a diva, she took fright and turned him down. Some years later, during the unrest in Paris after the fall of the Second Empire in 1871, Papin sends to the sisters a young woman whose life has been threatened. Her name is Babette Hersant, his letter tells them, and she's an excellent cook who would be a fine housekeeper for them. Babette (Stéphane Audran) takes up residence with them and proves to be invaluable, bringing Parisian skills at seeking out the best food in the markets and bargaining for the best price. And then one day Babette receives word that an old lottery ticket has finally paid off to the tune of 10,000 francs. It is also the hundredth anniversary of the founding of the small congregation, and Babette proposes that she cook a dinner for the elderly, cranky, often fractious flock to celebrate. What the sisters don't know, but will soon learn, is that Babette had been one of the most celebrated chefs in Paris. The film climaxes in a triumphant union of the spiritual and the physical, as Babette's feast transforms the group into a true fellowship. Axel stages the feast beautifully, and cinematographer Henning Kristiansen emphasizes the transformation wrought by Babette's food with a steady focus on the faces of the congregants, which change from icy gray to rosy warmth as the meal progresses. There's a lovely little moment in which one of the sternest of the group reaches for a glass, discovers that it's filled with water, makes a face, and eagerly picks up a wine glass instead. As I've said, it's an ephemeral film, and I certainly don't think it deserved the Oscar over the more complex and powerful Au Revoir les Enfants, but on the other hand, what's so bad about feeling good?

Wednesday, April 26, 2017

The Last of Sheila (Herbert Ross, 1973)

Actor Anthony Perkins and songwriter Stephen Sondheim moonlighted as screenwriters to create this jeu d'esprit, a murder mystery involving the kind of elaborate games that Perkins and Sondheim and their friends used to play: treasure hunts with ingenious clues. The setup is this: A year earlier, Sheila, the wife of film producer Clifton Green (James Coburn), was killed in a hit-and-run accident. Green invites six people who were at a party the night of her death to spend a week on his yacht, which is named for her. Before they board, he arranges them for a photo under her name on the prow of the yacht. Then he announces that he is going to give each of them an envelope that contains a secret: something that a person would want to conceal about themselves. Each night, they will dock at a different location and will be given a clue that they must follow to discover the secret. If the person who holds the card with the secret on it solves the puzzle, the hunt of the night is over. So, on the first night, the clues lead to the secret: "Shoplifter." And when Philip (James Mason), a washed-up film director who holds that clue, solves it, the game ends. But the next night, the game isn't completed: Green is found murdered during the hunt. Meanwhile, realization dawns in the group that the secrets were their own: Philip wasn't a shoplifter, but the actress named Alice (Raquel Welch) admits that she once lifted a valuable fur coat from a store. And when the secret for the night Green is killed is revealed to be "Homosexual," Tom (Richard Benjamin), a screenwriter, admits that he and Green once had a brief affair. And so it appears that Green was murdered by someone who didn't want their secret to come out. But just when it appears that the murder has been solved, there's another intricate twist. The screenplay is fiendishly clever, and it's well acted: The other players include Dyan Cannon as a high-powered agent, Joan Hackett as Tom's rich heiress wife, and Ian McShane as Alice's manager-husband. Unfortunately, Herbert Ross directs things a little clunkily, although some of the awkwardness may come from the fact that shooting began on the yacht itself, but bad weather held up the shoot and sets eventually had to be constructed on a soundstage. There was also reportedly some conflict among the cast members and the director, centering on Welch. Today, some of the film's attitudes seem a little antique: Homosexuality is no longer such a terrible secret, although at the time Perkins and Sondheim, both of whom were gay, were still closeted. And perhaps not enough is made of the fact that one of the clues outs a character as a former child molester. The resulting film is something like a soufflé that didn't rise, turning out tasty but a little chewy. The best moments belong to, not surprisingly, Cannon, one of those performers who make every film they're in a little better.

The Seventh Seal (Ingmar Bergman, 1957)

Back in the day, by which I mean the early 1960s, The Seventh Seal was one of the films -- along with Rashomon (Akira Kurosawa, 1950) and La Dolce Vita (Federico Fellini, 1960) -- that you had to have seen just to be considered culturally literate. Its stock has fallen considerably since then, thanks to a distaste for Ingmar Bergman's inquiries into faith. I hadn't seen it for many years until I decided to watch it last night, and I was expecting my reaction to be similar to the one I had recently watching Bergman's Through a Glass Darkly (1961): too much talking, not enough showing. I had, in fact, remembered very little from The Seventh Seal beyond the knight playing chess with death and the final dance of death across the horizon -- both of which have been parodied and copied ever since. And it is, still, much too talky: Epigrams about God and Death pile up on one another tiresomely. But I had forgotten how human a fable it is. I think it succeeds where Through a Glass Darkly fails, partly because of setting: The glum isolation of the island in the later film puts all our concentration on the actors and the torment their characters inflict on one another. If Through a Glass Darkly is intended to raise questions about faith, about human beings' relationship to a god, it misses the mark. The world the characters of the film inhabit is not a world energized by faith, so their preoccupation with it seems pointless. But the setting of The Seventh Seal is an age of faith -- perhaps the last one our civilization will ever know -- which adds an urgency to the characters' wrangling with it. It became obvious to me on this viewing that the key character is not the knight, Antonius Block (Max von Sydow), but his squire, Jöns (Gunnar Björnstrand), the sardonic commentator on the events. Jöns is our surrogate, the skeptic with a decidedly modern view of his era's religious extremism, such as the Crusade he and the knight have just been on. What we're witnessing is the merciful escape from a god that for some reason Bergman's modern characters keep hunting: the god of certainty -- the kind of certainty that breeds fanaticism and bigotry. In the end, Bergman's knight sacrifices himself to Death (Bengt Ekerot) so that ordinary people -- the players Jof (Nils Poppe) and Mia (Bibi Andersson) and their child -- may live to continue their secular amusements that had earlier been interrupted by fanatics and flagellants. Commentators have sometimes likened the plague that threatens the world of The Seventh Seal to the threat of nuclear annihilation, but I think that misses the point: For the medieval world, the Plague was a test of faith; for the modern world, the Bomb is a test of humanity. .

Monday, April 24, 2017

The Makioka Sisters (Kon Ichikawa, 1983)

I haven't read the novel by Junichiro Tanizaki on which Kon Ichikawa based The Makioka Sisters, but it seems to me that he has turned it into something like a Jane Austen novel made by Merchant Ivory.* The lushly melancholy scene at the beginning of the film in which the sisters walk through the blossoming cherry orchards in Kyoto, accompanied by an instrumental arrangement of Handel's aria "Ombra mai fu" from Serse, anticipates by two years the scenes in Tuscany in the Merchant Ivory version of E.M. Forster's A Room With a View (James Ivory, 1985) that are set to music like Puccini's "O mio babbino caro" and "Chi il bel sogno di Doretta." The Jane Austen parallel is even stronger: The plot consists of finding a husband for one of the sisters, Yukiko (Sayuri Yoshinaga), whose marital prospects are endangered by the unconventional behavior of her younger sister, Taeko (Yuko Kotegawa), just as Jane and Elizabeth Bennet's were by the scandalous behavior of their sister, Lydia, in Pride and Prejudice. And just as Austen's novels took place against the distant background of the Napoleonic wars, so do the Japanese military incursions into China -- the film begins in the spring of 1938 -- recede into the background of the domestic problems of the Makioka sisters. There are four Makioka sisters, the proud remnants of a family whose male line has died out, but the husbands of the two oldest sisters, Tsuruko (Keiko Kishi) and Sachiko (Yoshiko Sakuma), have adopted the family name and are helping rebuild its fortunes. The sisters adhere to the family tradition that older sisters must marry before younger, which Taeko, the youngest, rebels against. As the film begins, she has already tried to elope with the irresponsible Okuhata (Yonedanji Katsura), and although the family thwarted that attempt, the story made it into the newspapers, which incorrectly reported Yukiko as the one who tried to elope. The family demands a retraction, but the newspaper only issues a correction. Yukiko is beautiful but shy, and attempts by a matchmaker to arrange a marriage for her have fallen through. There is a wonderful scene in which the family goes to meet a suitor, who turns out to be a terrible but funny bore. Ichikawa, who co-wrote the screenplay with Shinya Hidaka, develops and individualizes the characters of the sisters and their husbands well, and stays just this side of romantic sentimentality. The cinematography by Kiyoshi Hasegawa makes the most of the colorful settings -- spring cherry blossoms and autumn foliage -- and especially the beautiful costumes of Keiko Harada and Ikuko Murakami. Only occasionally does the note intrude that this is an ephemeral world, soon to be swept away by war.

*No, I know. Ismail Merchant and James Ivory never filmed a Jane Austen book. But those who did, like Ang Lee with Sense and Sensibility (1995), were surely working in the Merchant Ivory mode.

*No, I know. Ismail Merchant and James Ivory never filmed a Jane Austen book. But those who did, like Ang Lee with Sense and Sensibility (1995), were surely working in the Merchant Ivory mode.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)