|

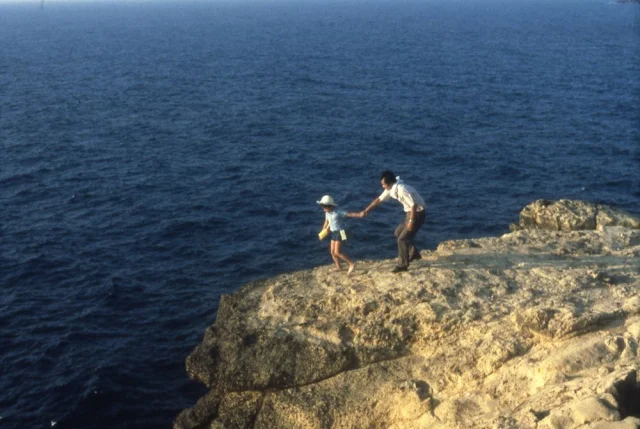

| Anil Chatterjee and Madhabi Mukherjee in The Big City |

Subrata Mazumdar: Anil Chatterjee

Himangshu Mukherjee: Haradhan Bannerjee

Edith Simmons: Vicky Redwood

Priyogopal, Subrata's Father: Haren Chatterjee

Sarojini, Subrata's Mother: Sefalika Devi

Bani, Subrata's Sister: Jaya Bhaduri

Pintu: Prasenjit Sarkar

Director: Satyajit Ray

Screenplay: Satyajit Ray

Based on stories by Narendranath Mitra

Cinematography: Subrata Mitra

Art direction: Bansi Chandragupta

Film editing: Dulal Dutta

Music: Satyajit Ray

For a long time, cities got a bad rap in the movies: Think of Fritz Lang's soul-devouring futuristic city in Metropolis (1027), the hedonistic town that sends out tendrils like the sinister Woman From the City to ensnare country folk like The Man and The Wife in F.W. Murnau's Sunrise (1927), or the weblike New York City that blights the lives of John and Mary in The Crowd (King Vidor, 1928). But these are surviving remnants of the Romanticism that proclaimed "God made the country and man made the town." By the mid-20th century, even our poets, or at least our songwriters, had turned the great big city into a wondrous toy, just made for a girl and boy, and a place where if you can make it there, you can make it anywhere -- a heroic challenge. In The Big City, Satyajit Ray's Kolkata retains some of the old sinister qualities, but it also represents opportunity, especially for women emerging from the shadows of male domination. Ray's domestic drama doesn't set up a contrast between town and country so much as a contrast between the dark, cramped home that Subrata and Arati Mazumdar share with his mother and father and sister and their young son, and the expanse of the city, which offers up tempting alternatives to the tight nuclear household. And those alternatives are something that the older members of that household view with disgust and horror: Arati's going out to work and to supplement the small income of the traditional breadwinner, Subrata. A world opens up for Arati, though it's also a world that can easily crumble around her. Madhabi Mukherjee's wonderful performance as Arati, tremulous and naive at first but gradually gaining fire and courage, animates the film. Obstacles present themselves: Subrata loses his job as a bank clerk, and Arati eventually loses hers by standing up for the Anglo-Indian Edith. But at the end, husband and wife, who have found their marriage tested by her employment, summon up reserves of courage to face the job market. The ending has been criticized as sentimental, but Ray has so carefully shown the growth of both Arati and Subrata that I find it hopeful.