A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Monday, October 31, 2016

Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! (Pedro Almodóvar, 1989)

The vivid Technicolor imagination of Pedro Almodóvar doesn't serve him as well in Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! as it did in his immediately previous hit film Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (1988). This film feels rather like an uneasy mashup of a romantic comedy and a bondage porno. Actually, "porno" is too strong a word, for even though Tie Me Up! received an NC-17 rating on its release in the United States, there's very little in it that can't be seen any night on the mainstream shows of pay-cable outlets like HBO and Showtime. The most explicit scenes involve Marina (Victoria Abril) taking a bath with a mechanical tub toy shaped like a frogman that nuzzles into her private parts -- a scene that's more funny than erotic -- and an extended sex scene with Marina and Ricky (Antonio Banderas) that's undeniably erotic but not especially revealing -- it mainly shows their upper bodies, except for an overhead shot that reveals Banderas's posterior. What's more objectionable -- especially in the context of today's renewed dialogue about rape and sexual harassment in the context of the presidential campaign -- is the film's central plot premise: Ricky, who has just been released from a mental institution (whose director and nurses he has been happily bedding), kidnaps film star Marina, whom he once picked up and had sex with during an escape from the institution. In the course of trying to make Marina fall in love with him, Ricky keeps her tied up. Eventually, she finds herself falling in love with him, and the film ends with Ricky going off to live with her and her family. It can be argued that the premise is freighted with irony: Ricky's attempt to win Marina leads to his being severely beaten by the drug dealers he goes to see to procure something to relieve her toothache and other pains -- as a recovering drug addict, Marina finds almost any painkiller short of morphine ineffective. The kidnapper gets a measure of punishment for his misdeed, in other words. But the film's unsteady tone and the somewhat pat "happy ending" don't overcome the essentially distasteful sexual politics of the premise. Though it's a misfire, the movie gets good performances out of Banderas and Abril, as well as Loles León as Marina's exasperated sister, Lola, and Francisco Rabal as Marina's director, desperately trying to control the chaotic production of what may be his last film. The brightly colorful sets by production designer Esther Garcia, art director Ferran Sánchez, and set decorator Pepon Sigler, and the cinematography by José Luis Alcaine are also a plus.

Sunday, October 30, 2016

The Lavender Hill Mob (Charles Crichton, 1951)

The late 1940s and early 1950s were a golden age for British film comedy, and Alec Guinness was right at the heart of it with his roles in The Lavender Hill Mob, Kind Hearts and Coronets (Robert Hamer, 1949), The Man in the White Suit (Alexander Mackendrick, 1951), The Captain's Paradise (Anthony Kimmins, 1953), and The Ladykillers (Mackendrick, 1955). It was the period when comic actors like Margaret Rutherford, Terry-Thomas, Alastair Sim, and the young Peter Sellers became stars, and British filmmakers found the funny side of the class system, economic stagnation, and postwar malaise. For it wasn't a golden age for Britain in other regards. Some of the gloom against which British comic writers and performers were fighting is on evidence in The Lavender Hill Mob, but it mostly lingers in the background. As the movie's robbers and cops career around London, we get glimpses of blackened masonry and vacant lots -- spaces created by bombing and still unfilled. The mad pursuit of millions of pounds by Holland (Guinness) and Pendlebury (Stanley Holloway) and their light-fingered employees Lackery (Sidney James) and Shorty (Alfie Bass) seems to have been inspired by the sheer tedium of muddling through the war and returning to the shriveled routine of the status quo afterward. Who can blame Holland for wanting to cash in after 20 years of supervising the untold wealth in gold from the refinery to the bank? "I was a potential millionaire," he says, "yet I had to be satisfied with eight pounds, fifteen shillings, less deductions." As for Pendlebury, an artist lurks inside the man who spends his time making souvenir statues of the Eiffel Tower for tourists affluent enough to vacation in Paris. "I propagate British cultural depravity," he says with a sigh. Screenwriter T.E.B. Clarke taps into the deep longing of Brits stifled by good manners -- even the thieves Lackery and Shorty are always polite -- and starved by the postwar rationing of the Age of Austerity. Clarke and director Charles Crichton of course can't do anything so radical as let the Lavender Hill Mob get away with it, but they come right up to the edge of anarchy by portraying the London police as only a little more competent than the Keystone Kops. The film earned Clarke an Oscar, and Guinness got his first nomination.

Saturday, October 29, 2016

Oldboy (Park Chan-wook, 2003)

It's about as improbable a premise for a thriller you'll find: A man, out on a drunken spree, wakes up imprisoned in what looks like a cheap hotel room where he stays, not knowing who put him there or why, for 15 years. His only contact with the outside world is a television set; his food is slipped to him through a slot in the door, and occasionally gas that puts him to sleep is pumped in the room so that it can be cleaned while he is unconscious. Then one day he is suddenly released and provided with cash and a cell phone. He begins to hunt compulsively for answers about who has done this to him. It's a mad plot, riffing on themes of guilt and obsession that are worthy of Kafka or Dostoevsky, but instead are cast in the idiom of horror movies and martial arts films. Eventually, the protagonist, Oh Dae-su (Choi Min-sik), will find the answers to what he seeks, but the truth will be more shattering than satisfying. Oldboy won the Grand Prix at the Cannes Festival, and no one who knows movies will be surprised to find that the jury was presided over by Quentin Tarentino, who gets the same inspiration from violent pop culture that Park Chan-wook demonstrates. The screenplay for Oldboy, on which Park shares credit with Lim Chun-hyeong and Hwang Jo-yun, was based on a Japanese manga. Park has said that he named his protagonist Oh Dae-su as a near homonym for Oedipus, who shared a similar fate when he discovered the truth, but Oldboy is closer to Saw (James Wan, 2004) than to Sophocles. Nevertheless, Oldboy has provocative things to say about guilt and revenge, and Choi's performance as the abused and haunted Dae-su is superb. Yu Ji-tae is suavely menacing as the villain, and Kang Hye-jeong is touching as Mi-do, who aids Dae-su in his quest. The often startlingly grungy production design is by Ryu Seong-hie and the cinematography by Chung Chung-hoon. There is a stunningly accomplished long take in the middle of the film in which the camera follows Dae-su as he single-handedly battles an army of opponents in a hallway that stretches across the wide screen like a frieze on the entablature of a temple. For once, however, a tour-de-force display of cinema technique doesn't overwhelm the rest of the film.

Friday, October 28, 2016

Young Frankenstein (Mel Brooks, 1974)

No telling how many times I've seen this blissful comedy, but I always find something new in it. This time, I was struck by Mel Brooks's musicality. There's the great "Puttin' on the Ritz" number, obviously, and Madeline Kahn bursting into an orgasm-induced rendition of "Ah, Sweet Mystery of Life" as Jeanette MacDonald never sang it. But the score by John Morris is wonderful on its own, as in the serenade to the monster on violin and horn played by Frederick (Gene Wilder) and Igor (Marty Feldman). And even the gag references sing: Frederick's appropriation of Mack Gordon's lyrics to "Chattanooga Choo Choo" when he arrives at the Transylvania (get it?) Station, or the supposedly virginal Elizabeth (Kahn) singing "The Battle Hymn of the Republic." It's also surprising how little really smutty humor Brooks indulges in this time. There's Inga's (Teri Garr) appreciation of the monster's "enormous schwanzstucker," to be sure, but this is PG humor at worst. So many of the gags are just wittily anti-climactic, like Frau Blucher (Cloris Leachman) proclaiming that Victor Frankenstein "vas my ... boyfriend!" Or the Blind Man (Gene Hackman) wistfully calling out to the fleeing monster, "I was gonna make espresso." (Hackman ad-libbed this line, and many other gags in the film, such as Igor's movable hump, were improvised by the actors.) And has a spoof ever been so beautifully staged? The production design is by Dale Hennesy, who had the wit to track down and borrow the original sparking and buzzing laboratory equipment that Kenneth Strickfaden created for the first Frankenstein (James Whale, 1931). The equally evocative black-and-white cinematography is by Gerald Hirschfeld.

Thursday, October 27, 2016

Spectre (Sam Mendes, 2015)

How can there be, by current count, 24 James Bond films? (Not counting the 1967 spoof version of Casino Royale, which had no fewer than five directors, including John Huston.) Why has the series not run its course by now? It has survived regular cast changes, including its central character, who has been played by six different actors: The current Bond, Daniel Craig, had not even been born when the first film in the series, Dr. No (Terence Young, 1962), premiered. Even recurring characters have been recast: M, Miss Moneypenny, and Q have each been played by five actors, and M underwent a change from male to female when Judi Dench took over the role in GoldenEye (Martin Campbell, 1995), though the part reverted to male (Ralph Fiennes) at the end of Skyfall (Sam Mendes, 2012). Yet the series has retained a reassuring familiarity, even to the point of typically beginning with a spectacular action sequence that almost certainly can't be topped in the remaining parts of the film. In Spectre, Bond is in Mexico City, where he shoots a bad guy, setting off an explosion that has him scrambling to escape from the building's collapsing façade, then chases another bad guy escaping from the rubble onto a helicopter, on which they struggle for control as it careens wildly over the crowds celebrating the Day of the Dead in the Zócalo. Then come the credits and another Bond-film staple, the thematic pop song: This one, "Writing's on the Wall," sung by Sam Smith, who co-wrote it with Jimmy Napes, won an Oscar. And then it's down to the usual business: chastisement by M (Fiennes), gadgets by Q (Ben Whishaw), and pursuit of the villains seeking control of the world. In Spectre there are two: One, Max Denbigh (Andrew Scott), is trying to take over control of intelligence services all over the world, while the other is a familiar figure from earlier Bond films, Ernst Stavro Blofeld (Christoph Waltz), who is in cahoots with Denbigh. (Blofeld, who had been a regular supervillain in the Sean Connery era, was absent from the Bond films after 1983 because of copyright litigation that was settled before Spectre, which takes its title from Blofeld's global criminal organization, was filmed.) There are also vodka martinis, shaken not stirred, to be quaffed, and "Bond girls" to be bedded -- although in recent years, Bond's sex life has become less wildly promiscuous and the women have become more complex characters. In Spectre, one of them, Madeleine Swann, is played by Léa Seydoux, a more than capable actress who sometimes seems to be fighting against the limitations of the role, trying to make Madeleine a more interesting figure than the screenplay allows. So to return to the original question: Why do we still gravitate to the Bond films when there are more novel action-adventures to be had? The series has been so frequently imitated -- Tom Cruise's Mission: Impossible movies are virtually indistinguishable in formula from Bond films -- that maybe imitation suggests the answer: We crave the familiar, but we also relish the small surprises when the formula is tweaked. In Spectre, for example, M, Moneypenny (Naomie Harris), and Q all get out of the office and into the field for a change. Spectre is not quite as satisfying an outing as Skyfall, and there are signs of fatigue in Craig's performance, suggesting that his term as Bond has run its course -- though he has reportedly signed on for the next one. But longevity can be its own reward: We have become so comfortable with the formula that it still excites people to speculate about the next James Bond -- Tom Hiddleston? Idris Elba?

Wednesday, October 26, 2016

21 Grams (Alejandro González Iñárritu, 2003)

|

| Melissa Leo and Benicio Del Toro in 21 Grams |

Cristina Peck: Naomi Watts

Jack Jordan: Benicio Del Toro

Mary Rivers: Charlotte Gainsbourg

Michael: Danny Huston

Marianne Jordan: Melissa Leo

Director: Alejandro González Iñárritu

Screenplay: Guillermo Arriaga

Cinematography: Rodrigo Prieto

Music: Gustavo Santaolalla

An egg is an egg no matter how you scramble it. You can whip it into a meringue or a soufflé or an omelet, but it still retains its eggness. The same thing, I think, is true of melodrama: There's no disguising its improbabilities and coincidences, its short cuts around motive and characterization, its intent to surprise and shock. Mind you, I don't have anything against melodrama. Some of my favorite films are melodramas, just as some of our greatest plays, even some of Shakespeare's tragedies, are grounded on melodrama. It's just that you have to approach it without pretension, which is, I think, the chief failing of Alejandro González Iñárritu's 21 Grams. The melodramatic premise is this: The recipient of a heart transplant falls in love with the donor's widow, who then persuades him to try to kill the man who killed her husband. It's the stuff of which film noir was made, but Iñárritu takes screenwriter Guillermo Arriaga's premise and scrambles it, using non-linear narrative devices -- flashbacks and flashforwards -- and casting an unrelievedly dark tone over it, as well as reinforcing a pseudoscientific message in the title, which is explicated at the end of the film. In 1907, a Massachusetts physician named Duncan MacDougall tried to weigh the human soul: He devised a sort of death-bed scales, which would register any loss of weight at the moment a patient died, thereby demonstrating to his satisfaction -- if not to the medical and scientific communities -- that the weight of the soul was approximately three-quarters of an ounce, or 21 grams. I suspect that Arriaga and Iñárritu meant the allusion to this bit of nonsense metaphorically, but it doesn't come off that way. By the end of the film, we are so weighed down with the misery of its protagonists that it feels like sheer bathos. This is not to say that 21 Grams is a total loss as a film. Iñarritu is one of our most celebrated contemporary directors, with back-to-back Oscars for Birdman (2014) and The Revenant (2015) to prove it. I just don't think he's found himself yet, but has become too caught up in narrative gimmicks that prevent him from delivering a completely satisfying film. There is much in 21 Grams to admire: The performances of Sean Penn, Naomi Watts, Benicio Del Toro, and Melissa Leo are as fine as their reputations suggest they would be. The narrative tricks are done with great skill, especially with the aid of cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto, who uses color to make each of the narrative segments distinct from the others, so that when the film cuts from one to another, the viewer feels better oriented. And there's no denying the emotional impact of the film as a whole. It could hardly be otherwise, given the pain suffered by the protagonists: Cristina, who lost her husband and her two little girls; Jack, the ex-con who accidentally killed them and believes that it was all because Jesus wanted it to happen; and Paul, who finds his chance at a new life marred by knowledge that it was at the expense of other people's happiness. But in the end, all of this suffering is off-loaded onto us without any compensatory feeling of having been enlightened by it.

Tuesday, October 25, 2016

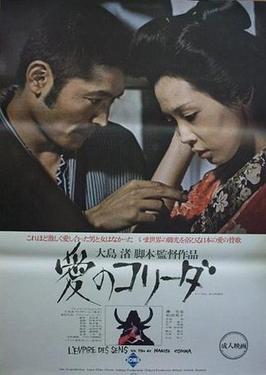

In the Realm of the Senses (Nagisa Oshima, 1976)

Even 40 years later, In the Realm of the Senses still has the power to shock, and not just because of the full nudity and unsimulated copulation -- we've all seen pornography in some form. It's that we've never seen them used in service of story, characterization, and theme as well as they are in this film. It's based on an actual incident that took place in Japan in 1936: Sada Abe killed her lover, Kichizo Ishida, during an experiment in erotic asphyxiation, then cut off his genitals and carried them with her for three days until she was arrested. Fascinated by this story, and by producer Anatole Dauman's suggestion that they should make a pornographic film, Oshima wrote the screenplay and set about putting together a cast and crew. The lead actors, Tatsuya Fuji as Kichizo and Eiko Matsuda as Sada, are extraordinary, transcending the mere shock value of their physical encounters with their commitment to illuminating the motives and the inner life of the couple. They give as complete a portrait of sexual obsession as we're ever likely to encounter in a movie. Oshima doesn't skimp on portraying the excesses of their passion: Sada persuades Kichizo to have sex with the 68-year-old geisha who comes to serenade them -- he is somewhat disgusted, but she is aroused when he does. The maids who tend to their room complain that it smells -- "We like it that way," Sada replies -- and the older man with whom Sada has been having sex to get money to support the lovers ends their relationship by saying she smells somewhat like a dead rat. But Oshima also portrays them as symbolic rebels against the militarism of 1930s Japan -- making love not war, if you will -- in a scene in which Kichizo, returning to Sada, passes marching troops being cheered by flag-waving schoolchildren. The real Sada was tried for his murder and mutilation, but served only five years in prison and became something of a folk legend in Japan, living on until the 1970s. A French and Japanese co-production, In the Realm of the Senses was filmed in Japan, but the footage had to be developed in France to avoid prosecution, and it has never been released in Japan without cuts or strategic blurring of its sex scenes. The movie is often quite beautiful, with cinematography by Hideo Ito and sets by Shigemasa Toda, but it's certainly not a film for all viewers.

Monday, October 24, 2016

My Man Godfrey (Gregory La Cava, 1936)

I don't know if director Gregory La Cava and screenwriters Morrie Ryskind and Eric Hatch intentionally set out to subvert the paradigm of the romantic screwball comedy in My Man Godfrey, but they did. It has all the familiar elements of the genre: the "meet-cute," the fallings-in and fallings-out, and the eventual happily-ever-after ending. And it is certainly one of the funniest members of the genre. William Powell is his usual suave and sophisticated self, and nobody except Lucille Ball ever played the beautiful nitwit better than Carole Lombard. But are Godfrey (Powell) and Irene (Lombard) really made for each other? Isn't there something really amiss at the ending, when Irene all but railroads Godfrey into marriage? Knowing that marriage is an inevitability in the genre, I kept wanting Godfrey to pair off with Molly (Jean Dixon), the wisecracking housemaid who conceals her love for him. And even Cornelia (Gail Patrick), the shrew Godfrey has tamed, seems like a better fit in the long run than Irene, with her fake faints and tears. The film gives us no hint that Irene has grown up enough to deserve Godfrey. Or is that asking too much of a film obviously derived from the formula? Perhaps it's just better to take it for what it is, and to enjoy the wonderful performances by Alice Brady, Eugene Pallette, Alan Mowbray, and Mischa Auer, and the always-welcome Franklin Pangborn doing his usual fussy, exasperated bit. A lot could be written, and probably has been, about how the film reflects the slow emergence from the Depression, with its scavenger-hunting socialites looking for a "forgotten man." a figure that only three years earlier, in Gold Diggers of 1933 (Mervyn LeRoy), had been treated with something like reverence in the production number "Remember My Forgotten Man." Had sensibilities been so hardened over time that the victims of the Depression could be treated so lightly? In any case, My Man Godfrey was a big hit, and was the first movie to have Oscar nominations -- for Powell, Lombard, Auer, and Brady -- in all four acting categories. It was also nominated for director and screenplay, though not for best picture.

Sunday, October 23, 2016

Kagemusha (Akira Kurosawa, 1980)

In the climactic moments of Kagemusha director Akira Kurosawa does something I don't recall seeing in any other war movie: He shows the general, Katsuyori (Ken'ichi Hagiwara) sending wave after wave of troops, first cavalry, then infantry, against the enemy, whose soldiers are concealed behind a wooden palisade, from which they can safely fire upon Katsuyori's troops. It's a suicidal attack, reminiscent of the charge of the Light Brigade, but Kurosawa chooses not to show the troops falling before the gunfire. Instead, he waits until after the battle is over and Katsuyori has lost, then pans across the fields of death to show the devastation, including some of the fallen horses struggling to get up. It's an enormously effective moment, suggestive of the dire cost of war. The film's title has been variously interpreted as "shadow warrior," "double," or decoy." In this case, he's a thief who bears a remarkable resemblance to the formidable warlord Takeda Shingen and is saved from being executed when he agrees to pretend to be Shingen. (Tatsuya Nakadai plays both roles.) This masquerade is designed to convince Shingen's enemies that he is still alive, even though Shingen dies soon after the kagemusha agrees to the ruse. The impostor proves to be surprisingly effective in the part, fooling Shingen's mistresses and winning the love of his grandson, and eventually presiding over the defeat of his enemies. But he gains the enmity of Shingen's son, Katsuyori, who not only resents seeing a thief playing his father but also holds a grudge against Shingen for having disinherited him in favor of the grandson. So when the kagemusha is exposed as a fake to the household, he is expelled from it, and Katsuyori's arrogance leads to the defeat in the Battle of Nagashino -- a historical event that took place in 1575. The poignancy of the fall of Shingen's house is reinforced at the film's end, when his kagemusha reappears in rags on the bloody battlefield, then makes a one-man charge at the palisade and is gunned down. The narrative is often a little slow but the film is pictorially superb: Yoshiro Muraki was nominated for an Oscar for art direction, although many of his designs are based on Kurosawa's own drawings and paintings, made while he was trying to arrange funding for the film. Two American admirers, Francis Ford Coppola and George Lucas, finally came through with the financial support Kurosawa needed -- they're listed as executive producers of the international version of the film, having persuaded 20th Century Fox to handle the international distribution.

Saturday, October 22, 2016

Intolerance (D.W. Griffith, 1916)

|

| The Belshazzar's Feast set for Intolerance |

|

| Edwin Long, The Babylonian Marriage Market, 1875. |

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)