A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Thursday, November 17, 2016

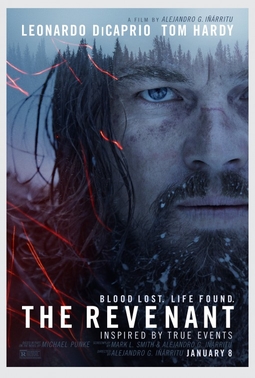

The Revenant (Alejandro González Iñárritu, 2015)

I have suggested before, in my comments on Birdman (2014), Babel (2006), and 21 Grams (2003), that in Alejandro G. Iñárritu's films there seems to be less than meets the eye, but what meets the eye, especially when Emmanuel Lubezki is the cinematographer, as he is in The Revenant, is spectacular. The Revenant had a notoriously difficult shoot, owing to the fact that it takes place almost entirely outdoors during harsh weather, and it went wildly over-budget. Leonardo DiCaprio underwent significant hardships in his performance as Hugh Glass, the historical fur trader who became a legend for his story of surviving alone in the wilderness after being mauled by a grizzly bear. In the end, it was a major hit, more than making back its costs and getting strong critical support and 12 Oscar nominations, of which it won three -- for DiCaprio, Lubezki, and Iñárritu. I won't deny that it's an impressive accomplishment, and probably the best of the four Iñárritu films I've seen. It's full of tension and surprises, and fine performances by DiCaprio; Tom Hardy as John Fitzgerald, the man who leaves Glass to die in the wilderness; and the ubiquitous Domhnall Gleeson as Andrew Henry, the captain of the fur-trapping expedition who aids Glass in his final pursuit of Fitzgerald. Lubezki's cinematography, filled with awe-inspiring scenery and making good use of Iñárritu's characteristic long tracking takes, fully deserves his third Academy Award, making him one of the most honored people in his field. The visual effects blend seamlessly into the action, especially in the harrowing grizzly attack. And yet I have something of a feeling of overkill about the film, which seems to me an expensive and overlavish treatment of a tale of survival and revenge -- great and familiar themes that have here been overlaid with the best that today's money can buy. The film concentrates on Glass's suffering at the expense of giving us insight into his character. It substitutes platitudes -- "Revenge is in God's hands" -- for wisdom. And what wisdom it ventures upon, like Glass's native American wife's saying, "The wind cannot defeat the tree with strong roots," is undercut by the absence of characterization: What, exactly, are Glass's roots?

Wednesday, November 16, 2016

O Brother, Where Art Thou? (Joel Coen and Ethan Coen, 2000)

On the scale for goofy Coen brothers films, O Brother, Where Art Thou? falls somewhere between Raising Arizona (1987) and The Big Lebowski (1998) from goofiest to least goofy. It is, I think, more over-the-top than is absolutely necessary, especially in the idiot hick accents adopted by John Turturro and Tim Blake Nelson in their roles. Or maybe they just seem that way because of the differently over-the-top performance of George Clooney as Ulysses Everett McGill, a man who thinks he talks more intelligently than he does. Still, I like Clooney in this mode, more than I do when he's playing a serious character, and it's to the Coens' credit that they cast him in the role: His performance gives an odd kind of off-balance stability to that of the other two. The chief glory of the movie, however, is its music, chosen by T Bone Burnett, superbly evoking a time and place. As for that time and place, Depression-era Mississippi, the movie pretty much ignores reality in favor of goofing around. It was the era of Bilbo and Vardaman, politicians of deeply cynical evil, and the rival candidates played by Charles Durning and Wayne Duvall don't even approach their horror, even when lampooning it. I laughed when the Ku Klux Klan performed what looked like a marching band half-time routine with a chant that evokes the parading monkey guards in The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming, 1939), but maybe it's the outcome of the recent presidential election that made me feel a little nauseated at even the notion of a comical Klan. A kind of irresponsibility mars the Coens' approach to the material, brilliantly funny as it often is. That said, the pacing of the movie is lively, and it's filled with ever-watchable performers like Durning, Holly Hunter, and John Goodman at their best. And there's always that music: If I'm inclined to forgive the Coens for their irresponsibility, it's because they introduced a lot of people who went out and bought the soundtrack album to some great music.

Tuesday, November 15, 2016

Children of Men (Alfonso Cuarón, 2006)

|

| Clive Owen in Children of Men |

Julian: Julianne Moore

Jasper: Michael Caine

Kee: Claire-Hope Ashitey

Luke: Chiwetel Ejiofor

Patric: Charlie Hunnam

Miriam: Pam Ferris

Syd: Peter Mullan

Nigel: Danny Huston

Marichka: Oana Pellea

Ian: Phaldut Sharma

Tomasz: Jacek Koman

Director: Alfonso Cuarón

Screenplay: Alfonso Cuarón, Timothy J. Sexton, David Arata, Mark Fergus, Hawk Ostby

Based on a novel by P.D. James

Cinematography: Emmanuel Lubezki

Production design: Jim Clay, Geoffrey Kirkland

Film editing: Alfonso Cuarón, Alex Rodríguez

Music: John Taverner

George Lucas did something shrewd when he prefaced his first Star Wars movie in 1977 with the phrase "A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away." Deliberately echoing the formulaic "Once upon a time," Lucas emphasized the fairy-tale essence of his science-fiction fable. But other creators of science fiction haven't been so careful, or perhaps have been more insouciant. George Orwell's 1984 was written in 1948, and all Orwell did was set the novel in a year that inverted the last two digits of the year of its completion. He wasn't presenting a literal forecast of actual life in the year 1984, he was serving as a prophet of what was actually present and nascent in his own time: totalitarianism and pervasive invasion of privacy. So 32 years later, we still find an uneasy resonance of Orwell's book in our own times. Similarly, when Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clark teamed to write the screenplay for 2001: A Space Odyssey (Kubrick, 1968), they weren't necessarily predicting deep exploration of the solar system and encounters with mysterious monoliths -- though I rather suspect they were hoping for at least the first -- but rather speculating on the origins of human nature and consciousness and their relationship to artificial intelligence. Similarly, the dystopian world of Blade Runner (Ridley Scott, 1982), populated by replicants and traversed by flying cars, is supposedly set in 2019 -- a year now close at hand -- but is also centrally concerned with the nature of humanity in a corporate capitalist society. What I'm getting at is that sometimes science fiction writers and filmmakers distance themselves as Lucas does from any notion that they're commenting on the "real world," but sometimes embrace a specific foreseeable date, with a view to making either a prediction of the way things will evolve or a comment on the problems of their own day. This is why I find Alfonso Cuarón's Children of Men such a puzzling film. It gives us a dank dystopian London that resembles the dank dystopian Los Angeles of Blade Runner, and it sets it in a specific time, the year 2027, a world in which human beings stopped bearing children 18 years earlier: i.e., in the year 2009 -- only three years after the film was made. But unlike Blade Runner, it doesn't seem to be telling us anything specific about either a predicted future or the way we lived then. It's a very entertaining film, full of violent action and suspense, with some wizardly work by Oscar nominees cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki and editors Cuarón and Alex Rodríguez. The way they handle the film's much-praised long-take sequences, aided by special effects to give the sense of complex action taking place in a single traveling shot, is exceptional -- anticipating Lubezki's work in making the entirety of Birdman (Alejandro González Iñárritu, 2014) seem to be a continuous take. There are also fine performances by Clive Owen, Julianne Moore, Chiwetel Ejiofor, Clare-Hope Ashitey, and the inevitably wonderful Michael Caine. But what is at the core of the film? Why does the failure of humankind to reproduce precipitate the worldwide cataclysm that the movie presents us? We have fretted so long about overpopulation that it would seem a blessing to have at least a pause in it, in which the world's scientists might take time to resolve the problem, or at least to discover the reason for the widespread infertility. Instead, we have a story that's largely about the mistreatment of immigrants. Why would non-reproducing immigrants, in a world with a declining population and therefore less pressure on natural resources, be a problem? Is it possible that this film, based on but radically altered from a novel by P.D. James, is promoting the extreme "pro-life" view, not only anti-abortion but also anti-contraception? Or is it simply that, as one character puts it, "a world without children's voices" is inevitably a terrible place? The film's failure to suggest a larger context for its action seems to me to by a weakness in an otherwise extraordinary film.

Monday, November 14, 2016

Pigsty (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1969)

Pier Paolo Pasolini's Pigsty is too much like what people think of when they hear the phrase "art house movie," especially when they have in mind films of the late 1960s. It's enigmatic and disjointed, and has a tendency to treat images as if they were ideas -- significant ideas. There are two narratives at work in the film: One features Pierre Clémenti as some kind of feral human wandering a volcanic landscape in which he finds a butterfly and a snake and eats both, then dons the helmet and musket he finds beside a skeleton. It's some unspecified pre-modern era -- the helmet and the garb of the soldiers and priests he meets later make think 17th century. He kills and eats another man he meets, then begins to gather a group of fellow cannibals. The other story takes place in Germany in 1967 and centers on Julian Klotz (Jean-Pierre Léaud), the son of a wealthy ex-Nazi (Alberto Lionello) who styles his hair and mustache like his late Führer and is pursuing a merger with a Herr Herdhitze (Ugo Tognazzi), who is a rejuvenated Heinrich Himmler, having undergone extensive plastic surgery. Julian, meanwhile, is an aimless youth who resists the urgings of his fiancée, Ida (Anne Wiazemsky) to join in leftist protest movements and to have sex with her. He'd rather spend time with the pigs in a nearby sty. The efforts at satire in the modern section are as heavy-handed as they sound in this summary, especially since Pasolini has chosen to have much of the exposition delivered by the actors in the flat-footed style of a 19th-century melodrama. There are some acting standouts, however, in both sections, especially Léaud, who seems to be having more fun than his role allows; Clémenti and Pasolini regular Franco Citti throw themselves into their feral roles, and Tognazzi is suavely menacing in his. If the whole thing is meant as a satire on dog-eat-dog (or man-eat-man or pig-eat-man) capitalism, it is sometimes too oblique and sometimes too blatant. Pasolini is a challenging, original filmmaker as always, but this one doesn't transcend the often inchoate artistic fervor of the '60s avant garde.

Sunday, November 13, 2016

In the Mood for Love (Wong Kar-wai, 2000)

In the British Film Institute's Sight and Sound critics' poll of the greatest films of all time, Wong Kar-wai's In the Mood for Love placed at No. 24, in a tie with Rashomon (Akira Kurosawa, 1950) and Ordet (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1955). I have to admit that I wouldn't rank it quite so high, especially putting it on a par with the other two films, but its intense, elliptical love story -- one in which there is no nudity, no sex scenes, and in fact not even a consummation of the affair -- is certainly unique and challenging. It's a film whose claustrophobic settings occasionally reminded me of the below-deck scenes in L'Atalante (Jean Vigo, 1934). The would-be lovers, Chow (Tony Leung Chiu-Wai) and Su Li-zhen (Maggie Cheung), are as trapped in their Hong Kong rooms as the newlyweds in L'Atalante are on their river barge, with the additional limitations that they are trapped in their marriages, in their offices, and in the social conventions of the 1960s. In one marvelous sequence she is trapped in his room when their landlady, Mrs. Suen (Rebecca Pan), comes home earlier than expected and then stays up all night playing mahjong with the neighbors, preventing her from leaving and adding fuel to the gossip but also fueling their intimacy. It's a masterstroke that we never see their respective spouses or even receive direct confirmation of what Chow and Su Li-zhen suspect: that her husband and his wife are having an affair with each other. They can't redouble the scandal by openly pairing off with each other, and in the end the paralysis becomes so ingrained in them that they are unable to consummate their relationship even when they are liberated from their claustrophobic living arrangements. Wong makes the most of the cinematography of Christopher Doyle and Mark Lee Ping-bin, framing them in the clutter of the offices where they work, focusing intensely on them as they meet in restaurants, using a variety of techniques such as slow motion and swish-pans, always with the effect of emphasizing their alienation. The score is often exquisitely appropriate, with themes by Michael Galasso and Shigeru Umebayashi as well as pop recordings by Nat King Cole and others. The historical references -- the tension evident in Hong Kong as it approaches the handover by Britain to China, a 1966 newsreel featuring Charles de Gaulle, Chow's final scene in Angkor Wat -- strike me as an unnecessary attempt to give the relationship of Chow and Su a connection to something larger than just a frustrated love affair. The story is poignant and resonant enough without them.

Saturday, November 12, 2016

The 47 Ronin (Kenji Mizoguchi, 1941)

|

| Chojuro Karawasaki in The 47 Ronin |

Friday, November 11, 2016

The Big Sleep (Howard Hawks, 1946)

|

| Humphrey Bogart and Martha Vickers in The Big Sleep |

Vivian Rutledge: Lauren Bacall

Eddie Mars: John Ridgely

Carmen Sternwood: Martha Vickers

Book Shop Owner: Dorothy Malone

Mona Mars: Peggy Knudsen

Bernie Ohls: Regis Toomey

Gen. Sternwood: Charles Waldron

Norris: Charles D. Brown

Lash Canino: Bob Steele

Harry Jones: Elisha Cook Jr.

Joe Brody: Louis Jean Heydt

Director: Howard Hawks

Screenplay: William Faulkner, Leigh Brackett, Jules Furthman

Based on a story by Raymond Chandler

Cinematography: Sidney Hickox

Art direction: Carl Jules Weyl

Film editing: Christian Nyby

Music: Max Steiner

I've cited Keats's "negative capability" before in warning about getting too involved with the literal details of a movie at the expense of missing the total effect, and it still seems appropriate here when it comes to figuring out exactly who did what to whom in Howard Hawks's The Big Sleep. Screenwriters William Faulkner, Leigh Brackett, and Jules Furthman are said to have consulted Raymond Chandler, the author of the novel they were adapting, about certain obscurities of the plot, and Chandler admitted that he didn't know either, which is as fine an example of being "in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason" as even Keats could come up with. So ask not who killed the Sternwoods' chauffeur, or even who really killed Shawn Regan -- if, in fact, Regan is dead. This is one of the most enjoyable of films noir, if a movie that has so many sheerly pleasurable moments can really be called noir. It's also one of the most deliciously absurd -- or maybe absurdist -- movies ever made, including its persistent presentation of Humphrey Bogart's Philip Marlowe as an irresistible hunk, who has bookstore clerks, hat check girls, waitresses, and female taxi drivers swooning at his presence. The only thing that makes this remotely credible is that Lauren Bacall, and not just Vivian Sternwood Rutledge, actually did. In his review for the New York Times, Bosley Crowther, one of the most obtuse critics who ever took up space in a newspaper, called it a "poisonous picture" and commented that Bacall "still hasn't learned to act" -- an incredible remark to anyone who has just watched her exchange with Bogart ostensibly about horse racing. This is, of course, one of Howard Hawks's greatest movies, and of course it received not a single Oscar nomination -- not even for Martha Vickers's delirious Carmen Sternwood. Vickers was so good in her role that her part had to be trimmed to put more focus on Bacall, who was being groomed for stardom. Sadly, Vickers never found another role as good as Carmen. Dorothy Malone, who did go on to stardom and an Oscar, steals her scene as the bookstore owner amused and aroused by Marlowe's charisma. And then there's Elisha Cook Jr. as a small-time hapless hood not far removed from the Wilmer who stirred Sam Spade's homophobia in The Maltese Falcon (John Huston, 1946). Except this time his demise elicits something Marlowe would seem otherwise incapable of: pity.

Monday, November 7, 2016

Excuses, Excuses

I watched Samurai Rebellion (Masaki Kobayashi, 1967) last night, but I'm not going to write about it today because I'm facing a deadline for a book review. Back with more posts after that's done.

Sunday, November 6, 2016

The Great Beauty (Paolo Sorrentino, 2013)

The great beauty referred to in the title of Paolo Sorrentino's film is Rome itself, which for millennia has transcended the ugliness that has overrun its seven hills. It's a city whose beauty and ugliness are seen in the film from the point of view of Jep Gambardella (Toni Servillo), who is celebrating his 65th birthday as the film begins. Jep first received acclaim 40 years earlier for a well-received novella, but the rest of his life has been spent as a celebrity journalist, interviewing and gossiping about the rich and famous. This career has earned him his own fame and fortune -- he lives in a luxurious apartment whose balcony overlooks the Colosseum. He's a bit like a straight Roman Truman Capote. The Rome in which Jep moves is filled with absurdity and excess: a performance artist who runs headlong into an ancient aqueduct; a little girl who has made millions by splashing canvases with paint and then smearing and tearing at them in a tantrum; a doctor who maintains a kind of assembly-line botox clinic in which patrons take numbers as if they were waiting in a delicatessen; a saintly centenarian Mother Teresa-style missionary whose spokesman is an oily dude with a shark-toothed grin; an archbishop considered next in line for the papacy who can only talk about food; and hordes of glitterati who spout inanities that they think will pass for wit. The Great Beauty is a satire, of course, but oddly it's a satire with heart: Jep Gambardella's long-since-broken heart. Servillo is terrific in the key role: elegant and cynical, but also capable of exposing idiots for what they are. Jep and the film in which he appears have obviously been compared to Marcello Mastroianni's character in La Dolce Vita (Federico Fellini, 1960), but Jep is less jaded than Marcello, less ground down by the decadence. And Sorrentino's view of his Rome is more genially ironic than Fellini's carnival of grotesques. Beautifully filmed by Luca Bigazzi, with a score by Lele Marchitelli augmented with works by contemporary composers like David Lang, Arvo Pärt, John Taverner, Henryk Górecki, and Vladimir Martynov, The Great Beauty was a deserving winner of the 2013 Oscar for foreign-language film.

Saturday, November 5, 2016

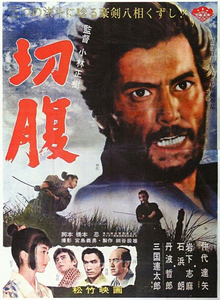

Harakiri (Masaki Kobayashi, 1962)

A study in tragic irony, Harakiri was intended as a commentary on Japan's history of hierarchical societies, from the feudal era through the Tokugawa shogunate and down to the militarism that brought the country into World War II and finally the corporate capitalism in which the salaryman becomes the latest iteration of the serf, pledging fidelity to a ruling lord. Working from a screenplay by Shinobu Hashimoto from a novel by Yasuhiko Takiguchi, director Masaki Kobayashi sets his film on a steady pace that at first feels static. There are long scenes of talk, with little moving except the camera's slow pans and zooms. But as Kobayashi's protagonist, Hanshiro Tsugumo (brilliantly played by Tatsuya Nakadai), tells his harrowing tale of loss, the film opens out into beautifully crafted scenes of action, as well as one terrifying and painful scene of cruelty, in which a man is made to commit the title's ritual disembowelment with a sword made of bamboo. Although there is an extended fight sequence in which Hanshiro takes on the entire household of the Ii clan, the true climax of the film is the duel between Hanshiro and Hikokuro Omodaka (Tetsuro Tanba), the greatest swordsman in the Ii household. Especially in this scene, the cinematography of Yoshio Miyajima makes a brilliant case for black and white film, aided by the editing of Hisashi Sagara that cuts between the dueling men and the waving grasses on the windswept hillside where the fight takes place. Harakiri is one of the best samurai films ever made, but even that observation contains its own note of irony, since Kobayashi's aim with the film is to validate his protagonist's assertion that "samurai honor is ultimately nothing but a façade."

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)