| Promotional posters for the 1955 American release of Summer With Monika |

A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Wednesday, December 30, 2015

Summer With Monika (Ingmar Bergman, 1953)

This early Bergman film, coming before the trifecta of Smiles of a Summer Night (1955), The Seventh Seal (1957), and Wild Strawberries (1957) established his reputation as a director, got its first exposure in the United States in 1955 when an enterprising distributor purchased the rights, cut it by a third, and released it as Monika, the Story of a Bad Girl, with a publicity campaign centered on Harriet Andersson's nude scene. As the original poster at left suggests, the Swedish distributors were not above exploiting Andersson either, but Bergman's adaptation with Per Anders Fogelström of Fogelström's novel, is anything but a naughty sexcapade. It's a film about disaffected youth: Monika and Harry (Lars Ekborg) are in their late teens and trapped in boring jobs. Monika works at a produce store where she is sexually harassed by the male employees, and Harry, a packer and delivery boy in a store that deals in pottery and glassware, is constantly being scolded for being late and lazy. Harry wants to study to be an engineer, but he has to look after his father, who is an invalid. His mother died when he was 8, and he tells Monika that he has always felt alone. Monika is anything but alone: Her father is abusive and her mother barely tends to Monika's noisy young siblings. So when Harry's father goes into a hospital, Monika persuades Harry to run away with her. They steal his father's boat and sail away from Stockholm to the countryside, beautifully filmed by Gunnar Fischer. Their idyll is eventually cut short by their lack of money and Monika's pregnancy. The problem with the film is that a rather puritanical tone eventually seeps in, making Monika the focus of a moral condescension that Bergman would outgrow as his career progressed.

Mon Oncle Antoine (Claude Jutra, 1971)

The title of Claude Jutra's richly textured film seems to promise a coming-of-age story, which is what, eventually, it delivers. But first the film acquaints us with a Quebec asbestos mining town in the 1940s. The first event we witness is a fight between a miner, Jos Poulin (Lionel Villeneuve), and his boss (Georges Alexander), which is hardly a fight at all because the boss speaks English and Jos doesn't, which easily allows him to ignore what the boss is saying and do what he wants to do: quit the mine and go look for work elsewhere. Our first look at Antoine (Jean Duceppe) is when he's doing his work as the town's undertaker: a comically macabre scene in which the corpse is denuded of the "suit" he was wearing for the viewing, which turns out to be a false front quickly plucked off the naked body and saved for another corpse, and the rosary is untwined from his stiffening fingers. Antoine is the owner, with his wife, Cecile (Olivette Thibault), of the town's general store, which employs his teenage nephew, Benoit (Jacques Gagnon); a teen girl, Carmen (Lyne Champagne), who lives at the store because her skinflint father (Benoit Marcoux), who pockets her earnings, doesn't want to pay for her upkeep; and Fernand (Jutra), who clerks at the store. It's Christmas time, though there's not much sentiment in the film's treatment of the holiday. One of the best scenes in the movie comes when the mine boss rides through the town in a little two-wheeled cart, tossing cheap gifts to the children as the grownups frown at his stinginess and comment that he hasn't given out any raises or bonuses. Benoit and a friend throw snowballs at the horse, causing the boss to beat a hasty retreat. One of the most celebrated of Canadian films, Mon Oncle Antoine benefits from Jutra's adaptation with Clément Perron of Perron's story, and from Michel Brault's cinematography, but most of all from the great credibility of its cast.

Tuesday, December 29, 2015

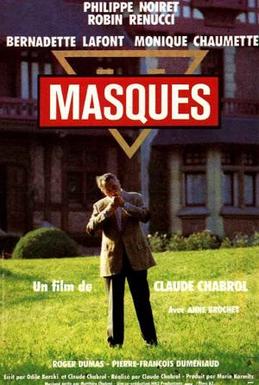

Masques (Claude Chabrol, 1987)

Masques shares the style (and the one-word title) of those 1960s romantic thrillers like Charade (Stanley Donen, 1963), Arabesque (Stanley Donen, 1966), and Kaleidoscope (Jack Smight, 1966) that inevitably got called "Hitchcockian." So it's not surprising that Chabrol, who recognized Hitchcock's genius when Hollywood still thought of him as just a popular entertainer, should cast an hommage to the director in their manner. Roland Wolf (Robin Renucci) is writing a biography of Christian Legagneur (Philippe Noiret), who hosts a cheesy TV talent/game show featuring senior citizens, so he comes to spend a week at Legagneur's estate near Paris. There he's introduced to a houseful of eccentrics: Legagneur's mute chauffeur/cook, Max (Pierre-François Dumeniaud); his secretary, Colette (Monique Chaumette); and a couple, Manu (Roger Dumas), a wine connoisseur who is helping stock Legagneur's cellar, and his wife (or perhaps mistress), who is a masseuse and reads tarot cards (Bernadette Lafont). (Lafont gets third billing after Noiret and Renucci, though hers is decided a secondary role, perhaps because she appeared in Chabrol's first film, Le Beau Serge, in 1958, and worked with him again several times during their long careers.) But most intriguing of all to Wolf is Legagneur's pretty young goddaughter, Catherine (Anne Brochet), who Wolf is told is recovering from a serious illness and is quite fragile. It's clear to the audience from Catherine's erratic behavior that she's drugged -- whether as part of her therapy or not is the question raised in Wolf's mind. For no one in this household is exactly what they seem, least of all Wolf, who, when he's alone in his room, removes a gun from his shaving kit and hides it on a shelf. On the shelf he finds a lipstick and with it, murmuring "Madeleine," he writes a large "M" on a mirror, then rubs it out. Madeleine, we will learn, is Wolf's sister, who is said to have quarreled with Catherine and then left on a trip to the Seychelles, which Wolf seriously doubts. Madeleine is also, of course, the name of the character played by Kim Novak in Hitchcock's Vertigo (1958), one of several "Easter eggs" for Hitchcockians left by Chabrol in the film. Legagneur's TV show, for another example, uses as theme music Gounod's "Funeral March for a Marionette," which was the theme music for Hitchcock's own TV show. Masques failed to find an American distributor when it was first released, but is now available on video. It's definitely minor Chabrol, but Noiret is terrific as the affably sinister Legagneur.

Monday, December 28, 2015

La Cérémonie (Claude Chabrol, 1995)

|

| Valentin Merlet, Jacqueline Bisset, Virginie Ledoyen, and Jean-Pierre Cassel in La Cérémonie |

Sophie: Sandrine Bonnaire

Georges Lelièvre: Jean-Pierre Cassel

Catherine Lelièvre: Jacqueline Bisset

Melinda: Virginie Ledoyen

Gilles: Valentine Merlet

Jérémie: Julien Rochefort

Mme. Lantier: Dominique Frot

Priest: Jean-François Perrier

Director: Claude Chabrol

Screenplay: Claude Chabrol, Caroline Eliacheff

Based on a novel by Ruth Rendell

Cinematography: Bernard Zitzerman

Production design: Daniel Mercier

Film editing: Monique Fardoulis

Music: Matthieu Chabrol

Claude Chabrol's La Cérémonie begins with a long tracking shot through the window of a café, picking up Sophie as she walks toward her appointment with Catherine Lelièvre. Catherine is as chic as Sophie, boyishly dressed with her hair cut in too-short bangs, is drab. The Lelièvres need a housekeeper, Catherine tells her, and Sophie presents the letter of reference from her most recent employer. The interview is slightly awkward, partly because Sophie is oddly oblique in her answers. But Catherine has a large house in a remote location and she needs a housekeeper right away. When Catherine drives Sophie to the house, a young woman named Jeanne appears and hitches a ride to the village near the Lelièvres house; Jeanne, who is as brashly forward as Sophie is reserved, works in the village post office. At the house, Sophie meets Catherine's husband, Georges, a rather blustery businessman, and her son from a previous marriage, the teenage Gilles, and stepdaughter, a university student named Melinda. Sophie proves to be an excellent cook and a reliable maid-of-all-work, but we soon discover that she has a secret or two. One is that she's illiterate, the result of a profound dyslexia. She doesn't drive, being unable to pass a driving test, and pretends that she needs glasses. When Georges insists on taking her to an optometrist, she ducks out of the appointment and buys a cheap pair of drugstore glasses -- though even then she is unable to give the sales clerk the exact change. Waiting for Georges, she meets Jeanne again, and the two women strike up a friendship. Jeanne, it turns out, knows another secret of Sophie's, which is that she was accused of setting fire to her house, killing her disabled father. Jeanne herself was accused of abusing her daughter, born out of wedlock, and causing her death, but both women were acquitted for lack of evidence. And so the stage is set for a story of folie à deux that Chabrol and Caroline Eliacheff adapted from a novel, A Judgment in Stone, by Ruth Rendell. Bonnaire and Huppert are extraordinary in their contrasting styles: Bonnaire passive, almost autistic in manner, Huppert bold and outgoing. The climax, in which a frenzied Jeanne releases Sophie's pent-up hostility, is shattering.

Story of Women (Claude Chabrol, 1988)

"Women's business," according to the subtitle, is what Marie Latour (Isabelle Huppert) tells her husband (François Cluzet) is going on behind closed doors in their apartment. The business is abortion, which Marie provides for prostitutes and other women who are finding childbirth to be a burden during the German occupation of France. But "Women's Business" might also be an apt translation of the original title of Chabrol's film, Une Affaire de Femmes. Based on the true story of Marie-Louise Giraud, who went to the guillotine in 1943 for the abortions she had induced, Story of Women is a deeply feminist film, though never a preachy one. Huppert, as usual, gives an extraordinary performance, emphasizing not only her character's determination to do what she thinks is right for the women she knows, but also her profoundly fatal naïveté about the politics of the era in which she is living. "Women's business" is to survive the ignorance and brutality of men, by any means necessary, but it betrays Marie into some choices that a woman with more knowledge of the way the world works might avoid. She loses sight of the fact that she became an abortionist to survive the deprivation that threatens her life and that of her children, and becomes fixated on their greatly improved standard of living and the possibility that she might earn enough to fulfill her dream of becoming a professional singer. (A distant dream, as her performance of a song in an audition for a music teacher suggests.) In the end, she goes to a guillotine that is not the toweringly glamorous instrument of death we've grown accustomed to from films about the French Revolution, but a grim and shabby little affair cobbled together from plywood and sheet metal -- a fitting image for the shabbiness of the Vichy régime and its treatment of those it saw as a threat.

Sunday, December 27, 2015

Le Beau Serge (Claude Chabrol, 1958)

Le Beau Serge has been called the first film of the French New Wave because it was made before the first features by Claude Chabrol's fellow Cahiers du Cinéma critics, François Truffaut's The 400 Blows (1959) and Jean-Luc Godard's Breathless (1960). The two later films were bigger successes internationally, but the influence of Chabrol's debut on the look, the narrative, and the technique of film continued to be felt, and his next movie, Les Cousins (1959), established Chabrol's reputation. Like Truffaut and Godard, who made international stars of Jean-Pierre Léaud and Jean-Paul Belmondo with their features, Chabrol launched the careers of Gérard Blain and Jean-Claude Brialy, who appeared in his first two films. In Le Beau Serge, Blain plays the title role, a young man who, by staying in his provincial village (Chabrol's own home town of Sardent), becomes an alcoholic layabout, trapped in an unhappy marriage. Brialy plays François, an old friend of Serge's, who left Sardent and became a success, but now returns home after a long absence to recuperate from a lung ailment. The roles are striking in both the similarity to and the differences from the ones Blain and Brialy play in Les Cousins, which takes place in Paris, where Blain is the strait-laced provincial and Brialy is his dissipated cousin. Le Beau Serge follows François's somewhat misguided attempt to help Serge clean up his life, which is complicated when François begins an affair with Serge's sister-in-law, Marie (Bernadette Lafont). In the climax of the film, Serge's wife, Yvonne (Michèle Méritz), goes into labor with the child everyone in the village expects to be deformed or stillborn, as their first child was. In a howling snowstorm, François takes it on himself to go in search of the village's doctor, and then looks for Serge, who is sleeping off a drunk in a chicken coop. The concluding scene, of Serge convulsed in hysterical laughter, is profoundly ambiguous. Chabrol's use of the actual village of Sardent, including many of its townspeople as actors, is brilliantly done, greatly aided by Henri Decaë's cinematography. Les Cousins is a more sophisticated and satisfying film, but it really has to be seen in tandem with Le Beau Serge. Both actors are terrific, but Blain attracted more attention because of his supposed resemblance in both looks and style to James Dean, though to my mind he recalls Montgomery Clift more than Dean.

Saturday, December 26, 2015

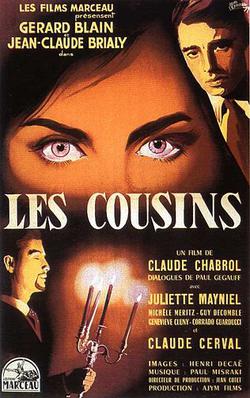

Les Cousins (Claude Chabrol, 1959)

Chekhov's gun plays a major role in Les Cousins, heightening the suspense about who will use it on whom. But the film isn't a suspense thriller, despite Chabrol's admiration for Hitchcock, so much as it is a deliciously perverse adaption of some classic fables: the country mouse and the city mouse, and the ant and the grasshopper. It also resonates ironically with Balzac's Lost Illusions, the novel that a bookseller (Guy Decomble) allows Charles (Gérard Blain) to "steal" from his shop. In the Balzac novel, a young man from the provinces goes to Paris to seek fame, fortune, and love, and his misadventures wreak havoc on himself and the people he loves. In Les Cousins, country mouse/ant Charles goes to Paris to share an apartment with his cousin, Paul (Jean-Claude Brialy), the city mouse/grasshopper, while both study law. Paul is a somewhat decadent hedonist, who tries to introduce the straiter-laced Charles, who is very much dedicated to his mother back home, to the delights of the city. One of these delights is the promiscuous Florence (Juliette Mayniel), with whom Charles falls in love, only to have things end badly when she chooses to live with Paul instead. Chabrol fills the movie with quirky, somewhat sinister characters, though never turns the film into a clear-cut tale of good vs. evil. Innocence doesn't triumph over cynicism here, though cynicism pays a price, which is what makes Chabrol's film such a grandly satisfying one to watch and to think about afterward. Blain and Brialy (in a suitably Mephistophelean mustache and beard) are brilliant, and the cinematographer, Henri Decaë, gives us a grand evocation of Paris in the 1950s.

Friday, December 25, 2015

Sweet Smell of Success (Alexander Mackendrick, 1957)

What do Sweet Smell of Success, His Girl Friday (Howard Hawks, 1940), Sullivan's Travels (Preston Sturges, 1941), and The Searchers (John Ford, 1956) have in common? They are all among the critically acclaimed films that, among other honors, have been selected for inclusion in the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress. And none of them received a single nomination in any category for the Academy Awards. Sweet Smell is, of course, a wickedly cynical film about two of the most egregious anti-heroes, New York newspaper columnist J.J. Hunsecker (Burt Lancaster) and press agent Sidney Falco (Tony Curtis), ever to appear in a film. They make the gangsters of Francis Ford Coppola's and Martin Scorsese's films look like Boy Scouts. So given the inclination of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences to stay on the good side of columnists and publicists, we might expect it to shy away from honoring the film with Oscars. But consider the categories in which it might have been nominated. The best picture Oscar for 1957 went to The Bridge on the River Kwai (David Lean), a respectable choice, and Sidney Lumet's tensely entertaining 12 Angry Men certainly deserved the nomination it received. But in what ways are the other nominees -- Peyton Place (Mark Robson), Sayonara (Joshua Logan), and Witness for the Prosecution (Billy Wilder) -- superior to Sweet Smell? The best actor Oscar winner was Alec Guinness for The Bridge on the River Kwai, another plausible choice. But Tony Curtis gave the performance of his career as Sidney Falco, overcoming his "pretty boy" image -- in fact, the film makes fun of it: One character refers to him as "Eyelashes" -- by digging deep into his roots growing up in The Bronx. Burt Lancaster would win an Oscar three years later for Elmer Gantry (Richard Brooks), a more showy but less controlled performance than the one he gives here. Either or both of them would have been better nominees than Marlon Brando was for his lazy turn in Sayonara, Anthony Franciosa in A Hatful of Rain (Fred Zinnemann), Charles Laughton in Witness for the Prosecution, and Anthony Quinn in Wild Is the Wind (George Cukor). The dialogue provided by Clifford Odets and Ernest Lehman for the film crackles and stings -- there is probably no more quotable, or stolen from, screenplay, yet it went unnominated. So did James Wong Howe's eloquent black-and-white cinematography, showing off the neon-lighted Broadway in a sinister fashion, and Elmer Bernstein's atmospheric score mixed well with the jazz sequences featuring the Chico Hamilton Quintet. Even the performers in the film who probably didn't merit nominations make solid contributions: Martin Milner is miscast as the jazz musician who falls for Hunsecker's sister (Susan Harrison), but he hasn't yet fallen into the blandness of his famous TV roles on Route 66 and Adam-12, and Barbara Nichols, who had a long career playing floozies in movies and on TV, is surprisingly touching as Rita, one of the pawns Sidney uses to get ahead. As a director, Alexander Mackendrick is best known for the comedies he did at Britain's Ealing Studios with Alec Guinness, The Man in the White Suit (1951) and The Ladykillers (1955). His work on Sweet Smell was complicated by clashes with Lancaster, who was one of the film's executive producers, and after making a few more films he accepted a position as dean of the film school at the California Institute of the Arts in 1967, where he spent the rest of his career as an instructor after resigning his administrative position. Sweet Smell currently has a 98% favorable rating on Rotten Tomatoes's Tomatometer and an 8.2 rating on the IMDb.

Niagara (Henry Hathaway, 1953)

Niagara was one of three movies starring Marilyn Monroe that were released in 1953. The other two, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (Howard Hawks) and How to Marry a Millionaire (Jean Negulesco), were hits, confirming what we now know: that Monroe was a peerless comedian, not, as Niagara wants her to be, a film noir siren. She had done earlier turns in legitimate film noir, a small role in The Asphalt Jungle (John Huston, 1950), larger ones in Clash by Night (Fritz Lang, 1952) and Don't Bother to Knock (Roy Ward Baker, 1952), so this time 20th Century-Fox decided to go all out in exploiting her as a femme fatale. There are many things wrong with Niagara, one thing being that it can't quite decide whether it's a noir thriller or a Technicolor travelogue about the eponymous falls and their various tourist attractions. But what's most wrong about it is its misuse of Monroe, who is not even the real lead character in the film: Her role is decidedly secondary to that of Jean Peters. And she is grotesquely exploited in her part as Rose Loomis, unhappily married to a mentally unstable man (Joseph Cotten) and plotting to have her lover (Richard Allan) bump him off. The studio can't resist dressing her in skin-tight clothes, with high heels that make it impossible for her to walk without bumps and grinds, and flaming red lipstick that's obviously freshly put on even when she's supposed to be waking up in the morning. A producer less under the control of the studio than Charles Brackett (who also wrote the clunky screenplay with Walter Reisch and Richard L. Breen) might have made Rose into a credible character, but here she's only an adolescent boy's fantasy. But even a misused Marilyn is better than no Marilyn at all, as we find out two-thirds of the way through the movie when the focus shifts to the character played by Peters and her grinning ass of a husband (Max Showalter), and we have nothing to marvel at but the Falls. If the screenplay had fallen into the hands of a Hitchcock, Niagara might have been a success, but Henry Hathaway directs as if he's bored by the whole thing.

Thursday, December 24, 2015

Annie Hall (Woody Allen, 1977)

|

| Diane Keaton and Woody Allen in Annie Hall |

Annie Hall: Diane Keaton

Rob: Tony Roberts

Allison: Carol Kane

Tony Lacey: Paul Simon

Pam: Shelley Duvall

Robin: Janet Margolin

Mom Hall: Colleen Dewhurst

Duane Hall: Christopher Walken

Director: Woody Allen

Screenplay: Woody Allen, Marshall Brickman

Cinematography: Gordon Willis

Costume design: Ruth Morley

Annie Hall is generally recognized as the movie that took Woody Allen from being a mere maker of comedy films like Bananas (1971) and Sleeper (1973) that were extensions of his persona as a stand-up comedian and into his current status as a full-fledged auteur, with a record-setting 16 Oscar nominations as screenwriter, along with seven nominations as director (the same number as Steven Spielberg, and only one less than Martin Scorsese). It is one of the few outright funny movies to have won the best picture, and also won for Diane Keaton's performance and Allen's direction and screenplay. Watching it today, in the light of his later work, I still find it fresh and original and frankly more satisfying than most of his later films. Marshall Brickman shared the screenwriting Oscar for Annie Hall and was also nominated along with Allen for the screenplay of Manhattan (1979), as was Douglas McGrath for Bullets Over Broadway (1995), one of his most entertaining later movies. Is it possible that Allen should have worked with a collaborator more often? Would that have curbed his tendency to overload his movies with existentialist conundrums and his increasingly creepy fascination with much younger women -- viz., Emma Stone in Irrational Man (2015) and Magic in the Moonlight (2014), Evan Rachel Wood in Whatever Works (2009), and Scarlett Johansson in Scoop (2006) and Match Point (2005)? But it does Allen's achievement in Annie Hall a disservice to view the film in light of his later career (and his private life). He made a step, not a leap, forward from the goofy early comedies by playing on his stand-up persona -- the film opens and ends with Alvy Singer (Allen) cracking jokes and includes scenes in which Alvy does stand-up at a rally for Adlai Stevenson and at the University of Wisconsin. What makes the movie different from the "early, funny ones" -- as a rueful running gag line goes in Stardust Memories (1980) -- is his willingness and ability to turn Alvy into a real person who just happens to be very funny. Keaton's glorious performance also succeeds in giving dimension to what could have been just a caricature. Annie Hall may not have deserved the best picture Oscar in a year that also saw the debut of Star Wars, Steven Spielberg's Close Encounters of the Third Kind, and Luis Buñuel's That Obscure Object of Desire, but it's easy to make a case for it.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)