A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Monday, April 18, 2016

Rififi (Jules Dassin, 1955)

The success of Rififi had a lasting effect on the "caper" or "heist" genre, which is still with us in one form or another, including the Mission: Impossible movies. Dassin's 30-minute sequence depicting the break-in and safe-cracking was hailed as a tour de force. I can't help wondering if Robert Bresson saw Rififi before he made his great 1956 film A Man Escaped, which takes a similar wordless and music-free approach to showing the preparations for Fontaine's prison break. Other than that, of course, nothing could be further from Fontaine's noble efforts to find freedom than the larcenous thuggery of Dassin's jewel thieves. Dassin knows, of course, that audiences respond positively to cleverness and skill, which is virtually all that his quartet of thieves have going for them. Tony (Jean Servais) is a brutal ex-con who beats his former mistress (Marie Sabouret) with a belt; Jo (Carl Möhner) is a swaggering, handsome guy for whom Tony took the rap for an earlier heist because Jo has a wife and child; Mario (Robert Manuel) is an easy-going ne'er-do-well; and César (Dassin under the pseudonym Perlo Vita) is a professional safe-cracker. Dassin manipulates us into thinking of these guys as heroes, if only because the gang led by Pierre Grutter (Marcel Lupovici), who wants to muscle in on their ill-gotten gains, is even worse. In the end, both sides are wiped out, but not before Jo's little boy (Dominique Maurin) is kidnapped and held for ransom. The final sequence of the film is particularly harrowing, especially to contemporary viewers used to mandated seatbelts and conscientious childproofing: A dying Tony drives the 5-year-old boy across Paris in an open convertible as the delighted kid stands on and even clambers over the seats of the speeding car. For all its unpleasantness, Rififi is as memorable as it was influential. It led to countless imitations, usually more light-hearted, including Dassin's own Topkapi (1964). It also revived Dassin's career, which had been at a standstill after he was blacklisted in Hollywood; Rififi's international success was a defiant nose-thumbing directed at HUAC's witch hunts.

Sunday, April 17, 2016

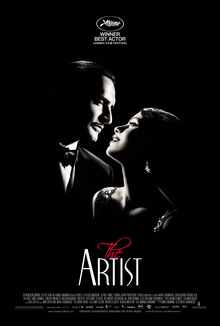

The Artist (Michel Hazanavicius, 2011)

There are two classic movies about the effect of the arrival of sound on films and the people who were silent-movie stars, Singin' in the Rain (Stanley Donen and Gene Kelly, 1952) and Sunset Blvd. (Billy Wilder, 1950). Neither of them won the Academy Award for best picture. Coming half a century later, Michel Hazanavicius's The Artist, which did, looks oddly like an anachronism. It is certainly a tour de force: a mostly silent film with a few witty irruptions of sound in the middle when the protagonist George Valentin (Jean Dujardin), having learned that his career as a film star is ending, suddenly begins to hear sounds, even though he seems incapable of producing them himself. (At the end of the film, Valentin speaks one line, "With pleasure," revealing his French accent.) The project grew out of Hazanavicius's admiration of silent films and their directors, and it fulfilled his own desire to make one himself. The title and the central predicament of George Valentin are an acknowledgement of the fact that silent film is a distinct art form, one lost with the advent of sound. At the expense of his career, Valentin insists on preserving the art -- much as Charles Chaplin did by refusing to make City Lights (1931) and Modern Times (1936) into talkies, long after sound had taken hold. But Valentin is no Chaplin, and his effort, an adventure story in the mode of the films that had made him famous, is a flop, coincidentally opening on the day in 1929 when the stock market crashed. Meanwhile, a younger fan and something of a protégée of his, Peppy Miller (Bérénice Bejo), becomes a huge star in talkies. From this point on, the script almost writes itself, especially if you've seen any of the versions of A Star Is Born, which is why some of us wonder how this undeniably entertaining film became such a hit and a multiple award-winner. It was nominated for 10 Academy awards and won half of them: picture, actor, director, costume design (Mark Bridges), and original score (Ludovic Bource). To my mind, Hazanavicius's screenplay is at fault for not making Valentin's supine reaction to sound entirely credible: Is it actor's ego? A fear of the new? Embarrassment at his accent? And the decision to play Valentin's suicide attempt as comedy feels like a failure of tone on the part of the writer-director. That said, the performances by Dujardin, Bejo, and the always invaluable John Goodman as the studio boss keep the movie alive. I just don't think it belongs in the company of Singin' in the Rain and Sunset Blvd.

Saturday, April 16, 2016

Wild Strawberries (Ingmar Bergman, 1957)

The portrait of old age in Wild Strawberries was created by a writer-director who was 39, which is about the right time for someone to become obsessed with the past and with the portents of dreams. In the film, Isak Borg (Victor Sjöström) is 78, and by that time -- speaking as one who is nearing that age -- most of us have come to terms with the past and made sense of (or perhaps just accepted as a given) the memories and dreams that persist in haunting us. But although Bergman's film, one of the handful of breakthrough films he made in the mid-1950s, may not ring entirely true psychologically, it holds up thematically. Isak Borg is about to be commemorated with an honorary degree, one that stamps him as over the hill, and it's not surprising that it forces him to reflections about the course of his life. He is not about to go gentle into a night that he thinks of as neither good nor bad, but the journey he takes during the film -- this is an Ingmar Bergman "road movie," after all -- helps him decide to accept his life, mistakes and all. The brilliantly crabby performance by Sjöström holds it all together, even though the movie occasionally misfires: The squabbling young hitchhikers Anders (Folke Sundquist) and Viktor (Björn Bjelfenstam), who come to blows over religious faith, could almost be a self-parody of Bergman's own obsession, which would play itself out rather tiresomely in his "trilogy of faith," Through a Glass Darkly (1961), Winter Light (1963), and The Silence (1963). And the dream sequence in which Borg sees his late wife (Gertrud Fridh) and her lover (Åke Fridell) adds little to our understanding of the character. It's also possible to find the reconciliation of Borg's son (Gunnar Björnstrand) and daughter-in-law (Ingrid Thulin) a little too easily achieved, as if thrown in as a correlative to Borg's own affirmation. The radiant performance of Bibi Andersson in the double role of Borg's cousin Sara and the young hitchhiker who shares her name, however, almost brings the film into convincing focus. I don't think Wild Strawberries is a masterpiece, but it's certainly one of the essential films in the Bergman oeuvre.

Friday, April 15, 2016

42nd Street (Lloyd Bacon, 1933)

Julian Marsh: Warner Baxter

Dorothy Brock: Bebe Daniels

Peggy Sawyer: Ruby Keeler

Billy Lawler: Dick Powell

Abner Dillon: Guy Kibbee

Lorraine Fleming: Una Merkel

Ann Lowell: Ginger Rogers

Pat Denning: George Brent

Thomas Barry: Ned Sparks

Director: Lloyd Bacon

Screenplay: Rian James, James Seymour

Based on a novel by Bradford Ropes

Cinematography: Sol Polito

Art direction: Jack Okey

Songs: Al Dubin, Harry Warren

Costume design: Orry-Kelly

Choreography: Busby Berkeley

42nd Street is only mildly naughty, bawdy, or sporty, as the lyrics of Al Dubin and Harry Warren's title song would have it, but once Busby Berkeley takes over to stage the three production numbers at the movie's end, it is certainly gaudy. What naughtiness and bawdiness it contains would not have been there at all once the Production Code went into effect a year or so later. It's doubtful that Ginger Rogers's character would have been called "Anytime Annie" once the censors clamped down, or that anyone would say of her, "She only said 'no' once and then she didn't hear the question." Or that it would be so clear that Dorothy Brock is the mistress of foofy old moneybags Abner Dillon. Or that there would be so many crotch shots of the chorus girls, including the famous tracking shot between their legs in Berkeley's "Young and Healthy" number. Although it's often remembered as a Busby Berkeley musical, it's mostly a Lloyd Bacon movie, and while Bacon is not a name to conjure with these days, he does a splendid job of keeping the non-musical part of the film moving along satisfactorily. It helps that he has a strong lead in Warner Baxter as the tough, self-destructive stage director Julian Marsh, balanced by such skillful wisecrackers as Rogers, Una Merkel, and Ned Sparks. But it's a blessing that this archetypal backstage musical became a prime showcase for Berkeley's talents. Dick Powell's sappy tenor has long been out of fashion, and Ruby Keeler keeps anxiously glancing at her feet while she's dancing, but Berkeley's sleight-of-hand keeps our attention away from their faults. Nor does anyone really care that his famous overhead shots that turn dancers into kaleidoscope patterns would not be visible to an audience in a real theater. In the "42nd Street" number, Berkeley also introduces his characteristic dark side: Amid all the song and dance celebrating the street, we witness a near-rape and a murder. It's a dramatic twist that Berkeley would repeat with even greater effect in his masterpiece, the "Lullaby of Broadway" number from Gold Diggers of 1935. Berkeley's serious side, along with the somewhat downbeat ending showing an exhausted Julian Marsh, alone and ignored amid the hoopla, help remind us that the studio that made 42nd Street, Warner Bros., was also known for social problem movies like I Am a Fugitive From a Chain Gang (Mervyn LeRoy, 1932) and the gangster classics of James Cagney, Humphrey Bogart, and Edward G. Robinson.

Thursday, April 14, 2016

Death in Venice (Luchino Visconti, 1971)

|

| Dirk Bogarde in Death in Venice |

Wednesday, April 13, 2016

The Virgin Spring (Ingmar Bergman, 1960)

The Virgin Spring was probably the first Bergman film I ever saw, and it made a powerful impression that stuck with me for 50-some years. I think that's one reason why I have mixed feelings about it today. In outline, it's a simple tale based on a 13th-century Swedish ballad, in which a young girl on her way to church is raped and murdered, but from the ground where the crime took place, a spring of fresh water erupts miraculously. But watching it today I see a more complex story, full of moral ambiguities. The girl, Karin (Birgitta Pettersson), is not such a paragon as I remembered: She is spoiled and prideful, trying to sleep late and avoid the task of taking the candles to the church. She may not even be as innocent as she is thought to be: The servant, Ingeri (Gunnel Lindblom), who accompanies her says the reason she wants to sleep late is that she was out the previous night flirting with a boy. Karin's mother, Märeta (Birgitta Valberg), is on the one hand a religious fanatic given to self-torture, and on the other an indulgent parent unwilling to discipline her daughter. Karin's father, Töre (Max von Sydow), is divided between the Christian faith he has adopted and a furious desire to wreak revenge on the rapist-murderers. After he has killed the two men and the boy who accompanied them, he expresses remorse but also blames God for his daughter's fate. He vows to build a church on the site, and the spring gushes forth, but as a miracle it seems like a somewhat anticlimactic response to the horror that has gone before. (It's not like the site, where running water is copious, even needs another spring.) Bergman for once is working from a screenplay he didn't write: It's by Ulla Isaksson, which may be why the film is poised so ambiguously between Christian affirmation and Bergman's usual bleak alienation. It is, however, one of Bergman's most beautifully accomplished films, joining him with the cinematographer Sven Nykvist, with whom he had worked only once before (seven years earlier on Sawdust and Tinsel), and with whom he would form one of the great working partnerships in film history. In its evocation of medieval narrative and meticulous re-creation of a milieu (the production designer is P.A. Lundgren), it's superb. But as a film from one of the great modern directors it seems oddly anachronistic and insincere.

Tuesday, April 12, 2016

Persona (Ingmar Bergman, 1966)

There comes a time in the history of any art when the pressure to do something new is exceeded by the difficulty of finding that newness. I think Persona is a good example of that problem. By the mid-1960s we had seen the great innovations in filmmaking of Buñuel, Antonioni, Resnais, and Godard, among many others. So when Ingmar Bergman chooses to open Persona with a montage of apparently random images, or chooses to dwell on images of self-immolating Buddhist monks during the Vietnam war or children being rounded up by the Gestapo, or to repeat an entire scene, or to resort to a kind of Verfremdungseffekt by showing the director and his crew filming the scenes we're watching, we can mutter to ourselves, "Seen that one before." The remarkable thing is that none of this apparently derivative film and narrative technique seriously weakens the movie, which is one of Bergman's best. Even though we can dismiss the killing of the sheep in the opening montage as a kind of homage to (or borrowing from) Buñuel's Un Chien Andalou (1929), or point at the opening of Resnais's Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959) as another example of such a montage, or cite Godard's political engagement as a precursor of Bergman's use of Vietnam and the Holocaust in his film, none of that really matters. Persona stands firm on its own, largely because of the phenomenal performances of Bibi Andersson as Alma and Liv Ullmann as Elisabet, and the extraordinary art of Sven Nykvist's black-and-white cinematography. The only other film in Bergman's opus that seriously challenges it for primacy, I think, is Cries and Whispers (1972), and that largely because Bergman had by that time realized that innovation could be a dead end and that concentrating on story and character without cinematic tricks was all that was needed to make a successful film. The core of Persona lies in the fascinating, ever-shifting relationship between the mute Elisabet and the garrulous Alma, and we don't even need the sequence in which the images of the two actresses merge into one to get the point. It's sometimes said that the film works because Andersson and Ullmann look so much alike, but they really don't. Andersson has a kind of conventional prettiness: As I noted in my entry on The Devil's Eye (Bergman, 1960), she could almost pass as the heroine of a 1960s American sitcom like Donna Reed or Elizabeth Montgomery. Ullmann has a stronger face: a more determined gaze, powerful cheekbones, a fuller, more sensuous mouth. The two women could not have exchanged roles in the film without a serious disruption in their relationship: Even though she's three years younger than Andersson, Ullman has to play the mature, successful actress, and Andersson the eager young nurse. What gives their relationship in the film its marvelous tension is the sense that Alma is imbibing, in an almost vampiric way, the strength that Elisabet possessed before her onstage breakdown. Part of me wishes that Bergman had had the conviction to tell the two women's stories without the narrative gimmicks, but another part tells me that Persona has to be judged for what it is, and that it's one of the great films.

Links:

Bibi Andersson,

Ingmar Bergman,

Liv Ullmann,

Persona,

Sven Nykvist

Monday, April 11, 2016

Boyhood (Richard Linklater, 2014)

Academy voters had essentially two choices for best picture of 2014, not that there weren't six other nominees, two of them, The Grand Budapest Hotel (Wes Anderson) and Whiplash (Damien Chazelle), quite worthy of the honor. But Birdman (Alejandro González Iñárritu) and Boyhood were the front-runners, in large part because they took great risks. In addition to an often surreal approach to its subject matter, Birdman was filmed to give the illusion that most of it was one continuous take -- even though the narrative was not necessarily continuous. And Boyhood was filmed over the course of 12 years, as its protagonist, Mason (Ellar Coltrane), went from the age of 6 to 18 years old. Faced with two such groundbreaking but inimitable films, the Academy chose poorly: It went for the flashy technique of Birdman instead of the profoundly revealing story of the pressures a child faces in the process of growing up. But it's not just Mason's story, it's also that of his mother (Patricia Arquette), his sister (Lorelei Linklater), and his father (Ethan Hawke). Arquette deservedly won a supporting actress Oscar, but Hawke (who was nominated) also demonstrated the remarkable ability to adapt his persona over the extended filming time. The divorced parents face pressures, too: the mother the more immediate one of becoming a single parent and then making disastrously wrong choices as she remarries, the father the long-term one of remaining a presence in the lives of his children. He seems to have it easier than his ex-wife does, but every time Hawke re-appears in the film, he beautifully communicates the sense of having lost something precious. Like his son, he grows, shedding his fecklessness and irresponsibility, just as Mason learns to sift through the continuous barrage of advice from adults and find the wisdom to become his own person. I don't know of any film that so tenderly presents what the quotidian is like, without resorting to melodramatic crisis at its turning points. The only other films I can even compare it to are François Truffaut's The 400 Blows (1959) and Satyajit Ray's Aparajito (1956), which take place in much harsher milieus than the Texas towns and cities in which Linklater sets Boyhood. But even though that world is milder and more familiar than the places in France and India where Truffaut and Ray set their films, Boyhood reveals how the world shapes us -- or as Linklater puts it at the end of his film, "the moment seizes us" -- as well as those films do. I think it's a treasure that belongs in their august company.

Sunday, April 10, 2016

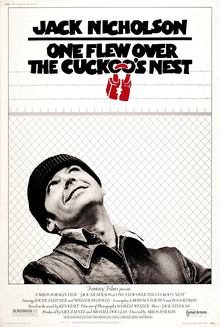

One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (Milos Forman, 1975)

One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest is beginning to show its age, as any 41-year-old movie must. It no longer exhibits the freshness that won it acclaim as a masterpiece and raked in the five "major" Academy Awards: picture, director, actor, actress, and screenplay -- only the second picture in history to do that: The first was It Happened One Night (Frank Capra, 1934), and only one other picture, The Silence of the Lambs (Jonathan Demme, 1991), has subsequently accomplished that feat. Today, however, One Flew has the look of a skillfully directed but somewhat predictable melodrama; its tragic edge has been blunted by familiarity. In treating the material, director Forman goes for straightforward storytelling, without showing us something new or personal as an auteur. And as time has passed, some of the elements of the source, Ken Kesey's novel, that screenwriters Laurence Hauben and Bo Goldman took pains to mitigate -- namely the countercultural glibness and antifeminism -- have begun to show through. It's harder today to wholeheartedly cheer on the raw, anarchic antiauthoritarianism of McMurphy (Jack Nicholson) or to accept as a given the unmitigated villainy of Nurse Ratched (Louise Fletcher). We want our protagonists and antagonists to be a little more complicated than the film allows them to be. There are still many who think it a great film, but if it is, I think it's largely because it's the perfect showcase for a great talent -- Nicholson's -- supported by an extraordinary ensemble that includes a shockingly young-looking Danny DeVito, Scatman Crothers, Sidney Lassick, Christopher Lloyd, Will Sampson, and a touchingly vulnerable Brad Dourif.

Saturday, April 9, 2016

Pulp Fiction (Quentin Tarantino, 1994)

|

| Uma Thurman and John Travolta in Pulp Fiction |

Honey Bunny: Amanda Plummer

Vincent Vega: John Travolta

Jules Winnfield: Samuel L. Jackson

Butch Coolidge: Bruce Willis

Marsellus Wallace: Ving Rhames

Mia Wallace: Uma Thurman

Capt. Koons: Christopher Walken

Fabienne: Maria de Medeiros

Winston Wolfe: Harvey Keitel

Brett: Frank Whaley

Jody: Rosanna Arquette

Lance: Eric Stoltz

Director: Quentin Tarantino

Screenplay: Quentin Tarantino, Roger Avary

Cinematography: Andrzej Sekula

Production design: David Wasco

Film editing: Sally Menke

Watching Pulp Fiction again -- I don't know how many times I've seen it but it feels like a lot -- I'm struck by how much the film is about language. In a way that's appropriate, given that it was nominated for seven Oscars but won only for the screenplay by Tarantino and Roger Avary. And certainly language comes to the fore in the way the film tramples on taboos like the f-word and the n-word, which are repeated so often that you're numbed to the expected shock. And then there's the great biblical tirade by Jules, extrapolated from a passage in Ezekiel and repeated three times to make sure we get the point that Jules is some kind of prophet. And of course there's the familiar pronouncement by Vincent that the French call a quarter-pounder with cheese a Royale with cheese. But throughout the film characters encounter semantic problems, as when Jules asks Brett what country he's from. The puzzled Brett asks, "What?" thereby provoking Jules's response, "'What' ain't no country I've ever heard of. They speak English in What?" Or when Esmeralda (Angela Jones) asks Butch what his name means, and Butch replies, "I'm American, honey. Our names don't mean shit." Or when Pumpkin calls out, "Garçon! Coffee!" and the waitress (Laura Lovelace) corrects him: "'Garçon' means boy." Pumpkin and Honey Bunny have even decided to give up robbing liquor stores because they're owned by "too many foreigners [who] don't speak fucking English." For Pulp Fiction's characters language is a means of establishing dominance, as when Winston Wolfe refuses Vincent's request to say "please" when he's giving orders. It's also a way of establishing intimacy: When Vincent brings Mia home after she has overdosed, she finally tells him the silly joke -- a pun on catch up/ketchup -- that she refused to tell him earlier. So maybe Pulp Fiction isn't exactly about language -- it's also about violence and God and a lot of other things -- but I don't know of many other recent films that are so memorable because of it.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)