A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Friday, June 24, 2016

Rio Bravo (Howard Hawks, 1959)

I could never countenance plagiarism, but as they say, if you're going to steal, steal from the best. Even if you're Howard Hawks stealing from Howard Hawks, which happens almost shamelessly in Rio Bravo. No one who loves Hawks's Red River (1948) as much as I do could fail to miss how much of Rio Bravo is, let us say, borrowed from that film. There's the byplay between Sheriff John T. Chance (John Wayne) and Stumpy (Walter Brennan), which echoes that of Dunson (Wayne) and Groot (Brennan) in Red River. Ricky Nelson's young gun Colorado Ryan is a reworking of Montgomery Clift's Matthew Garth. And Angie Dickinson's Feathers could almost be a parody of Joanne Dru's motormouth Tess Millay. But the Hawksian borrowings don't stop with Red River. When Feathers kisses Chance for the first time and then goes in for a second kiss in which he participates more enthusiastically, she comments, "It's better when two people do it," which is a direct steal from a similar scene in To Have and Have Not (Hawks, 1944) when "Slim" (Lauren Bacall) tells "Steve" (Humphrey Bogart), "It's even better when you help." The two movies share not only a director but also a screenwriter, Jules Furthman, who is joined in Rio Bravo by Leigh Brackett, who earlier worked together on another Bogart-Bacall-Hawks movie, The Big Sleep (1946). Even the composer of the score for Rio Bravo, Dimitri Tiomkin, gets into the borrowing game, taking a theme from his score for Red River and handing it over to lyricist Paul Francis Webster for the song, "My Rifle, My Pony, and Me," sung by Dean Martin's Dude and Nelson's Colorado. Rio Bravo isn't as great a movie as Red River by a long shot, and it probably signals some creative exhaustion on Hawks's part that he not only borrowed so heavily from his earlier work but also felt it necessary to remake Rio Bravo in two thinly disguised versions also starring Wayne, as El Dorado (1966) and Rio Lobo (1970). But is there a more entertaining self-plagiarism, and a surer demonstration of what made Hawks one of the great filmmakers?

Thursday, June 23, 2016

The Walk (Robert Zemeckis, 2015)

Many years ago in Rome I went with a group of other tourists to the top of the dome of St. Peter's where, stepping out onto the narrow observation platform, I experienced a moment of real terror. Stretching out below me, beyond a barrier that seemed to be only knee-high but was probably at least waist-high, were the ridges of the dome, extending downward like railway tracks into the abyss. They were dotted with metal disks that, the guide told us, mountaineers would place candles on to illuminate the dome at Christmastime. As I shrunk back as far from the guard rail as possible, I realized something about my fear of heights: I'm not afraid of falling so much as jumping. I realized that a momentary psychotic break could easily cause me to hurdle the barrier and plunge to my death. Maybe it was the perspective of the receding ridges that awoke this in me, but I had never experienced anything like it before, and even at the rim of the Grand Canyon I have never experienced it quite the same again. I have it under control. But I'm glad I didn't see The Walk in 3D in theaters, where I've heard that audience members fainted or fled as Philippe Petit (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) took his walk between the twin towers of the World Trade Center. Even watching it in 2D on a TV screen brought back that experience on the dome. And not so much during the walk on the wire as during the preparations, when Petit clambers around on the verge of the building to set up his equipment: There's something about being in the proximity of the crisis moment that knots me up. During the walk itself, the self-possession of Gordon-Levitt's Petit is somehow oddly calming. All of this is to say that The Walk is an oddly unique film in its success at portraying the narrowness of the line between heroism and foolishness. For Petít's walk was singularly foolish, and Gordon-Levitt does a wonderful job of presenting him as an engaging personality with an eccentric obsession that most of us can only marvel at and reluctantly admire. Zemeckis, who wrote the screenplay with Christopher Browne, deserves credit for blending characterization with state-of-the-art film technology that for once isn't used to fling things at the audience but to draw them into a precarious state. It felt like a return to the engaging Zemeckis of the Back to the Future films (1985, 1989, 1990) after the overblown Forrest Gump (1994), Contact (1997), and Cast Away (2000). Remarkably, the film gets away without sentimentalizing the calamitous fate of the twin towers and their inhabitants, although seeing them re-created with cinematic technology does create a subtext for Petit's performance. Only at the very end, when the image of the towers fades into a sunlit "11," do we get a subtle evocation of that date in September 2001.

Wednesday, June 22, 2016

Stalag 17 (Billy Wilder, 1953)

After their success with Sunset Blvd. (1950), Billy Wilder and Charles Brackett went their separate ways. They had been one of the most successful teams in Hollywood history since 1938, when they began collaborating as screenwriters, and then as a producer (Brackett), director (Wilder), and co-writer team starting with Five Graves to Cairo in 1943. But Wilder decided that he wanted to be a triple-threat: producer, director, and writer. His first effort in this line, Ace in the Hole (1951), was, however, a commercial flop. so he seems to have decided to go for the sure thing: film versions of plays that had been Broadway hits and therefore had a built-in attraction to audiences. His next three movies, Stalag 17, Sabrina (1954), and The Seven Year Itch (1955), all fell into this category. But what Wilder really needed was a steady writing collaborator, which he didn't find until 1957, when he teamed up with I.A.L. Diamond for the first time on Love in the Afternoon. The collaboration hit pay dirt in 1959 with Some Like It Hot, and won Wilder his triple-threat Oscar with The Apartment (1960). Which is all to suggest that Stalag 17 appeared while Wilder was in a kind of holding pattern in his career. It's not a particularly representative work, given its origins on stage which bring certain expectations from those who saw it there and also from those who want to see a reasonable facsimile of the stage version. The play, set in a German P.O.W. camp in 1944, was written by two former inmates of the titular prison camp, Donald Bevan and Edmund Trczinski. In revising it, Wilder built up the character of the cynical Sgt. Sefton (William Holden), partly to satisfy Holden, who had walked out of the first act of the play on Broadway. Sefton is in many ways a redraft of Holden's Joe Gillis in Sunset Blvd., worldly wise and completely lacking in sentimentality, a character type that Holden would be plugged into for the rest of his career, and it won him the Oscar that he probably should have won for that film. But it's easy to see why Holden wanted the role beefed up, because Stalag 17 is the kind of play and movie that it's easy to get lost in: an ensemble with a large all-male cast, each one eager to make his mark. Harvey Lembeck and Robert Strauss, as the broad comedy Shapiro and "Animal," steal most of the scenes -- Strauss got a supporting actor nomination for the film -- and Otto Preminger as the camp commandant and Sig Ruman as the German Sgt. Schulz carry off many of the rest. The cast even includes one of the playwrights, Edmund Trczinski, as "Triz," the prisoner who gets a letter from his wife, who claims that he "won't believe it," but an infant was left on her doorstep and it looks just like her. Triz's "I believe it," which he obviously doesn't, becomes a motif through the film. Bowdlerized by the Production Code, Stalag 17 hasn't worn well, despite Holden's fine performance, and it's easy to blame it for creating the prison-camp service comedy genre, which reached its nadir in the obvious rip-off Hogan's Heroes, which ran on TV for six seasons, from 1965 to 1971.

Tuesday, June 21, 2016

Ace in the Hole (Billy Wilder, 1951)

|

| Jan Sterling and Kirk Douglas in Ace in the Hole |

Lorraine Minosa: Jan Sterling

Herbie Cook: Robert Arthur

Jacob Q. Boot: Porter Hall

Al Federber: Frank Cady

Leo Minosa: Richard Benedict

Sheriff Gus Kretzer: Ray Teal

Director: Billy Wilder

Screenplay: Billy Wilder, Lesser Samuels, Walter Newman

Cinematography: Charles Lang

Music: Hugo Friedhofer

Ace in the Hole has a reputation as one of Billy Wilder's most bitter and cynical films. But today, when media manipulation is such a commonplace topic of discourse, it seems a little shy of the mark: After all, the manipulation in the movie seems to be the work of one man, Chuck Tatum, who milks the story of a man trapped in a cave-in to rehabilitate his own career. Other media types, including the editor and publisher of the small Albuquerque paper Tatum uses to springboard back into the big time, seem more conscientious about telling the truth. As we've seen time and again, it's the audience (the ratings, the ad dollars) that drives the news, with the journalists often reluctantly following. Wilder's screenplay, written with Lesser Samuels and Walter Newman, certainly blames them (or us) for the magnitude of Tatum's manipulation, but the focus on one unscrupulous reporter makes the media the primary evil. Maybe it's just because I've been following the Trump campaign this summer, and just watched the stunning eight-hour documentary about O.J. Simpson on ESPN, O.J.: Made in America, that I'm inclined to blame the great imbalance in what gets covered as news on the audience at least as much as on the reporters and editors who cater to their tastes. That said, Ace in the Hole is pretty effective movie-making -- so much so that it's surprising to learn that it was one of Wilder's biggest flops. It has some terrific lines, like the one from Lorraine, the trampy wife of the cave-in victim: When told by Tatum that she should go to church to keep up the appearance that she's still in love with her husband, she retorts, "I don't go to church. Kneeling bags my nylons." Porter Hall, one of Hollywood's great character actors, is wonderfully wry as the editor forced by Tatum into hiring him, and Robert Arthur, one of Hollywood's perennial juveniles, does good work as Herbie, the young reporter corrupted by Tatum's ambition. Sterling spent her long career typecast as a floozy, but that's probably because she did such a good job of it. Douglas is, as usual, intense, which has always made me feel a little ambivalent about him as an actor; I wish he would unclench occasionally, but I admire his willingness to take on such an unlikable role and make the character ... well, unlikable. He's the right actor for Wilder, who seems to be on the verge of trying to give Tatum a measure of redemption, but can't quite let himself do it.

Monday, June 20, 2016

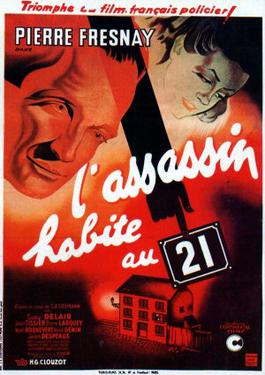

The Murderer Lives at Number 21 (Henri-Georges Clouzot, 1942)

Henri-Georges Clouzot is best-known today for the chilling Diabolique (1955) and the nail-biter The Wages of Fear (1953), but his first feature was a comedy-mystery somewhat in the manner of The Thin Man (W.S. Van Dyke, 1934). In The Murderer Lives at Number 21, police inspector Wenceslas Vorobechik (Pierre Fresnay), known as Wens, sets out to solve a series of murders in which the killer leaves a calling card: Monsieur Durand. Eventually, he is aided (and occasionally stymied) by his mistress, Mila Milou (Suzy Delair), who gets involved in the case because she thinks the celebrity of bringing the killer to justice would help her nascent career as a singer and actress. Clouzot made the film for a company backed by the occupying German forces, who wanted films to replace American imports. The movie shows no sign of Nazi propaganda, and there are those who claim that Clouzot inserted subtle anti-German jokes into the film. It was based on a novel by Stanislas-André Steenman, who worked on the screenplay with Clouzot, who brought the characters of Wens and Mila over from an earlier short film. Wens and Mila have a relationship somewhat reminiscent of Nick and Nora Charles, although no Thin Man film ever contained a scene like the one in which Mila squeezes out the blackheads on Wens's face -- a gratuitous bit that is presumably designed to show the intimacy of their relationship. Compared to Clouzot's later work, it's a slight but amusing movie, enlivened by the oddball inhabitants of the boarding house at No. 21 Avenue Junot that Wens moves into, disguising himself as a clergyman, after he receives a tip that the murderer lives there.

Sunday, June 19, 2016

The Hollywood Revue of 1929 (Charles Reisner, 1929)

Designed to show off the novelty of sound -- and, in two sequences, the coming novelty of Technicolor -- The Hollywood Revue of 1929 was enthusiastically received by critics and audiences, though it lost the best picture Oscar to The Broadway Melody (Harry Beaumont, 1929). Today, both movies are creaky antiques, despite the effort that MGM put into producing them. In fact, The Hollywood Revue often seems like an attempt to promote The Broadway Melody, which had opened three and a half months earlier, since it gives prominent spots to that film's stars, Charles King, Bessie Love, and Anita Page. The rest of it feels a lot like amateur night at MGM, as the studio's stars are trotted out for songs and skits that often feel tired and incoherent. In a few years, MGM would be boasting that it had more stars than there are in heaven, but many of the stars showcased in the Revue are forgotten today -- like King, Love, and Page -- or were on the wane -- like John Gilbert, Marion Davies, and Buster Keaton. The ones that remained stars, like Jack Benny and Joan Crawford, did so by reinventing themselves. The Revue, which modeled itself on theatrical conventions like the minstrel show and vaudeville, both of which were on the outs, failed to break ground for the Hollywood musical: It would take a few years for Warner Bros. to do that, with 42nd Street (Lloyd Bacon, 1933) and the unfettered imagination of Busby Berkeley taking the backstage musical formula of The Broadway Melody and some of Sammy Lee's choreographic tricks from the Revue -- including overhead kaleidoscope shots -- and improving on them. The Revue has a few highlights even today: Joan Crawford trying a little too hard to sparkle as she sings (passably) and dances (clunkily); Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy in their first sound film, doing a magic act with Jack Benny's intervention; Cliff Edwards and the Brox Sisters doing "Singin' in the Rain," which gets a Technicolor reprise with most of the company at the film's end; Keaton acrobatically clowning his way (silently) through an "underwater" drag routine; and Norma Shearer and John Gilbert in Technicolor performing a bit of the balcony scene from Romeo and Juliet, first as Shakespeare wrote it and then in 1929's slang. To get to them, however, you have to sit through a lot of dud routines and dated songs like Charles King's paean to maternity, "Your Mother and Mine," which must have been aimed right at the mushy heart of Louis B. Mayer.

Saturday, June 18, 2016

Tillie's Punctured Romance (Mack Sennett, 1914)

Tillie's Punctured Romance was Mack Sennett's first venture into feature-length production, and perhaps the first feature-length comedy ever made. Despite the later reputation of Charles Chaplin, it was designed as a starring vehicle and film debut for Marie Dressler, then the much bigger star. It was adapted from her Broadway hit, Tillie's Nightmare, and Dressler claimed that it was she who persuaded Sennett to cast Chaplin as her leading man. Adding Sennett's then-lover Mabel Normand, who also had a hand in developing Chaplin's early career, created a wonderful dynamic, but the teaming was never repeated: Chaplin's ambitions led him into writing and directing his own films; Normand and Sennett split in 1918, and her career suffered from her drug addiction and association with director William Desmond Taylor, whose murder in 1922 caused a scandal; Dressler was unable to establish a film career after the failure of two short films in which she also played Tillie, though she returned to the screen in 1927 after a nine-year absence. It's a shame, because Dressler was one of the few comic actresses capable of upstaging Chaplin, as their scenes together demonstrate. She had a rare gift for over-the-top physical comedy, which was Sennett's forte. For this anarchic comery, he marshaled all of his regular company, including Mack Swain and Chester Conklin, as well as the Keystone Kops, without ever eclipsing Dressler. Later in her career, Dressler would evoke pathos as well as laughs, but Sennett never lets Tillie be anything but a clown, except at the very ending, when she and Mabel share in their triumph over Chaplin's con man.

Friday, June 17, 2016

The Patsy (King Vidor, 1928)

King Vidor is not generally known as a comedy director, and The Patsy shows why: Vidor seems to have no sense of how to set up a gag, merely letting the skilled comic acting of Marion Davies as the put-upon younger sister, Pat Hamilton, and Marie Dressler and Dell Henderson as her parents, do the work. The result is a giddy, silly movie with a good many laughs, but not much coherence. Pat is smitten with Tony Anderson (Orville Caldwell), but her sister, Grace (Jane Winton) has her hooks in him -- until, that is, she starts running around with playboy Billy Caldwell (Lawrence Gray). Pat tries to win Tony by memorizing joke books -- for a silent film The Patsy is unusually heavy on gags in the intertitles -- but this only makes her parents, especially her domineering mother, think she's gone mad. Then she tries to make Tony jealous by pretending that she's in love with Billy, arriving at his house when he's drunk and trying to woo him by imitating movie stars like Mae Murray, Lillian Gish, and Gloria Swanson. Davies's skill and charm makes all of this palatable if not plausible, but almost every scene is stolen by Dressler, who uses face and body to upstage everyone. Vidor and Davies teamed again the same year for Show People, another comedy.

Thursday, June 16, 2016

The Divine Lady (Frank Lloyd, 1929)

Frank Lloyd is a director nobody remembers today except for the fact that he won two best director Oscars. Unfortunately, they were for movies that almost no one except film scholars and Oscar completists watch today: this one and Cavalcade (1933). His other distinction is that his Oscar for The Divine Lady is the only one that has ever been awarded for a film that was not nominated for best picture.* (As if to make up for this anomaly, Mutiny on the Bounty, which Lloyd also directed, won the best picture Oscar for 1935, but he lost the directing Oscar to John Ford for The Informer.) It's a moderately entertaining film about the affair of Emma Hamilton (Corinne Griffith) and Lord Horatio Nelson (Victor Varconi) -- a story better told in That Hamilton Woman (Alexander Korda, 1941) with Vivien Leigh and Laurence Olivier as the lovers. Griffith is one of those silent stars whose career didn't make it into the sound era, reportedly because her voice was too nasal. She was, however, considered* for the best actress Oscar, which went to Mary Pickford for Coquette. She doesn't have to speak in The Divine Lady: Although it has a synchronized music track, including Griffith supposedly singing (but probably dubbed) "Loch Lomond", and sound effects, including cannon fire during Nelson's naval battles, there is no spoken dialogue. The only truly standout performance is a small one by Marie Dressler as Emma's mother: She has a funny slapstick bit at the beginning of the movie, but disappears from the movie far too soon. The cinematography by John F. Seitz (miscredited as "John B. Sietz" in the opening titles) was also considered* for an Oscar, but it went to Clyde De Vinna for White Shadows in the South Seas (W.S. Van Dyke and Robert J. Flaherty, 1928).

*If you want to get technical about it, there were no official nominations in any of the Oscar categories for the 1928-29 awards. What are usually regarded as nominees are the artists and films that Academy records show were under consideration for awards. In Lloyd's case, he was also under consideration for directing the films Drag and Weary River during the same time period, but when his win was announced, only The Divine Lady -- which was not considered for a best picture Oscar -- was specified.

*If you want to get technical about it, there were no official nominations in any of the Oscar categories for the 1928-29 awards. What are usually regarded as nominees are the artists and films that Academy records show were under consideration for awards. In Lloyd's case, he was also under consideration for directing the films Drag and Weary River during the same time period, but when his win was announced, only The Divine Lady -- which was not considered for a best picture Oscar -- was specified.

Wednesday, June 15, 2016

On the Waterfront (Elia Kazan, 1954)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

_poster.jpg)

_poster.jpg)