A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Friday, December 16, 2016

The Lobster (Yorgos Lanthimos, 2015)

Thursday, December 15, 2016

Deadpool (Tim Miller, 2016)

Good nasty fun, and a fine example of having your cake and eating it too. By which I mean that, thanks to director Tim Miller, screenwriters Rhett Reese and Paul Wernick, and star Ryan Reynolds, Deadpool succeeds not only in sending up the destructive violence of comic-book superhero movies, but also in providing its own entertainingly destructive violence. Reynolds plays Wade Wilson, a former special forces op who, learning that he has cancer, submits to an experimental treatment that leaves him disfigured but invulnerable. And so it goes, as Wilson crafts a superhero costume to hide his disfigurement and calls himself Deadpool. (He takes his name from the "dead pool" run by his friend Weasel (T.J. Miller), who runs a bar whose regulars frequently get themselves into mortal scrapes and place bets on who'll get killed next.) No truth, justice, and the American way for Deadpool, whose chief aim is to get even with Ajax (Ed Skrein), who caused his disfigurement and claims to have a way of reversing it. The whole thing is an excuse for cynical wisecracks and the kind of destruction that in the usual superhero films is brought about by the fight against evil. In this case, Deadpool is only on the side of right by default: Ajax and his minions are so much worse. The film made a lot of money, surprising only those who thought that giving it an R rating -- for sex and naughty language as well as the usually more-tolerated violence -- would eliminate, or at least severely reduce, the supposed "core audience" for comic-book superhero movies: teenage boys. Deadpool does nothing to advance the art of film, but it still serves to expose the less idealistic side of superheroism.

Links:

Deadpool,

Ed Skrein,

Paul Wernick,

Rhett Reese,

Ryan Reynolds,

T.J.Miller,

Tim Miller

Wednesday, December 14, 2016

Salt of the Earth (Herbert J. Biberman, 1954)

|

| Striking miners in Salt of the Earth |

Sunday, December 11, 2016

Apocalypse Now (Francis Ford Coppola, 1979)

|

| Martin Sheen in Apocalypse Now |

Col. Kurtz: Marlon Brando

Lt. Col. Kilgore: Robert Duvall

Jay "Chef" Hicks: Frederic Forrest

Lance B. Johnson: Sam Bottoms

Tyrone "Clean" Miller: Laurence Fishburne

Chief Phillips: Albert Hall

Col Lucas: Harrison Ford

Photojournalist: Dennis Hopper

Director: Francis Ford Coppola

Screenplay: John Milius, Francis Ford Coppola, Michael Herr

Based on a novel by Joseph Conrad

Cinematography: Vittorio Storaro

Production design: Dean Tavoularis

Film editing: Lisa Fruchtman, Gerald B. Greenberg, Walter Murch

The familiar story of the confused and sometimes disastrous making of Apocalypse Now has been told many times, and never better than by Francis Ford Coppola's wife, Eleanor, in her 1991 documentary Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker's Apocalypse. So it's not worth going into here, except to note that the subtitle of her film plays on both the current meaning of the word "apocalypse" -- i.e., a disaster of great magnitude -- and the original one: a disclosure or revelation. It might be said that the enormous expenditure and hardship that Francis Coppola experienced during the making of Apocalypse Now was revelatory, not only to Coppola but also to the film industry, which was reaching the limits of its tolerance of unconstrained visionary filmmaking. It would cross that limit the following year with Heaven's Gate, Michael Cimino's film that took down a venerable production force, United Artists, along with its director. Coppola's career, unlike Cimino's, would recover, but he would never again be the director he was in his prime, with the first two Godfather films. And American filmmaking would never again be as prone to take risks as it was in the 1970s. As for the film itself, Apocalypse Now remains one of the essential American movies if only because it epitomizes the nightmare that was the Vietnam War. Coppola deserves much of the credit for this embodiment of Lord Acton's familiar dictum: "Power tends to corrupt. Absolute power corrupts absolutely." But there are others who should share the credit with him, including screenwriters John Milius and Michael Herr, who made the connection between Joseph Conrad's tale of imperialism gone wrong, Heart of Darkness, and the war. The ambience of the film is largely the work of production designer Dean Tavoularis, cinematographer Vittorio Storaro, who won a well-deserved Oscar, and Walter Murch and his sound team, who also won. And while Marlon Brando's Kurtz is a disappointment and Martin Sheen never quite meets the demands of his role as Capt. Willard, they are surrounded by marvelous support from Robert Duvall, Frederic Forrest, Dennis Hopper, and a very young and almost unrecognizable Laurence Fishburne (billed as Larry), among others.

Saturday, December 10, 2016

Die Nibelungen (Fritz Lang, 1924)

Die Nibelungen: Siegfried

|

| Hanna Ralph in Die Nibelungen: Siegfried |

Kriemhild: Margarete Schön

Brunnhild: Hanna Ralph

Siegfried: Paul Richter

King Gunther: Theodor Loos

Hagen Tronje: Hans Adalbert Schlettow

Mime / Alberich: Georg John

Die Nibelungen: Kriemhild's Revenge

|

| Margarete Schön in Die Nibelungen: Kriemhild's Revenge |

Queen Ute: Gertrud Arnold

King Gunther: Theodor Loos

Hagen Tronje: Hans Adalbert Schlettow

King Etzel: Rudolf Klein-Rogge

Slaodel: Georg John

Director: Fritz Lang

Screenplay: Fritz Lang, Thea von Harbou

Cinematography: Carl Hoffmann, Günter Rittau, Walter Ruttmann

Art direction: Otto Hunte, Karl Vollbrecht

Costume design: Paul Gerd Guderian, Aenne Willkomm

Music: Gottfried Huppertz

Fritz Lang's two-part epic, based on the Middle High German Nibelungenlied, will confuse anyone who knows the story only via Richard Wagner's Ring cycle: There are no Rhinemaidens or gods or Valkyries, nothing of Siegfried's parentage, and, since it lacks gods, consequently no Götterdämmerung. It consists of two films, Siegfried and Kriemhild's Revenge, that tell the story -- parts of which will be familiar from the final two operas in Wagner's cycle -- of how Siegfried slew the dragon and bathed in its blood, becoming invincible except for one spot on his back that the blood failed to touch, then killed the dwarf Alberich and took possession of a magic net that renders him invisible. He travels to Burgundy, where he wins the hand of the beautiful Kriemhild by helping her brother, King Gunther, subdue the warrior maiden Brunnhild. But Siegfried is killed after Gunther's advisor, Hagen, tricks Kriemhild into revealing his vulnerable spot. Brunnhild kills herself and Kriemhild vows revenge on the whole lot, which in the second film she accomplishes by marrying King Etzel, aka Attila, and provoking war between his Huns and the Burgundians. Lang tells the story with an eye-filling blend of tableaus, set-pieces, and scenes swarming with bloody action, concluding with a spectacular fire in which the Burgundians are trapped in Etzel's castle. The performances are pretty spectacular, too. Richter plays Siegfried as a muscular young goof ensnared by fate, Ralph is a formidable Brunnhild, and Schön modulates from naïve to terrifying as Kriemhild. But it's the production design by Otto Hunte and the costuming by Paul Gerd Guderian that lingers most in the memory. The production evokes late 19th- and early 20th-century book illustrators like Arthur Rackham and Walter Crane, but also the stark hieratic figures of Byzantine mosaics, especially Kriemhild, who becomes more powerfully static as the film progresses. Much has been written about the way the film fed into the heroic German myth that was co-opted by the Nazis, especially since the screenwriter, Thea von Harbou, Lang's wife at the time, later joined the party. (Lang, whose mother was Jewish, left Germany in 1934.) In fact, the Nazis sanctioned only the first half, Siegfried, after they came to power. Kriemhild's Revenge, with its depiction of the corruption of power and its nihilistic ending, didn't suit their purposes.

Friday, December 9, 2016

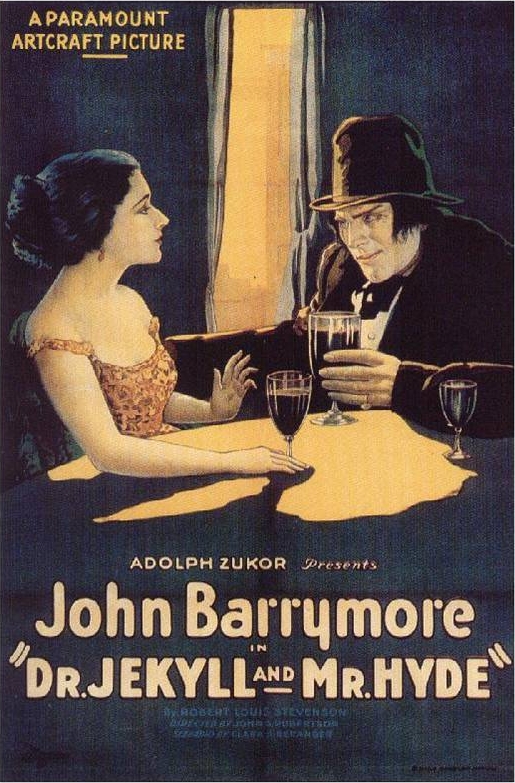

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (John S. Robertson, 1920)

Almost from the moment that Robert Louis Stevenson published his novella Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde in 1886, theatrical producers were snapping it up for adaptation. It was a great vehicle for ham actors who relished the transformation scenes, as long as it could be spiced up a little with a little sex -- the novella is more interested in the psychology of Jekyll/Hyde than in the lurking-horror and damsels-in-distress elements added to most stage and screen versions. There were several film versions before John Barrymore, the greatest of all ham actors, took on the role in 1920. It's an adaptation by Clara Beranger of the first major stage version by Thomas Russell Sullivan, who added a central damsel in distress as Jekyll's love. She's called Millicent Carewe (Martha Mansfield) in the film, which also adds a "dance hall girl" named Gina (Nita Naldi) to the mix. Mansfield is bland and Naldi is superfluous, though rather fun to watch when she goes into her "dance," which consists of a lot of hip-swinging and arm-waving. Barrymore, however, is terrific, giving his transformation into Hyde everything he's got in the way of contortions of face and body. Though the screenplay makes much of the distinction between the virtuous Jekyll and the dissolute Hyde, Barrymore manages to suggest the latency of Hyde in Jekyll even before he swallows the sinister potion -- a reversion to Stevenson's original, in which Jekyll is not quite the upstanding fellow the adaptations tried to make him.

Wednesday, December 7, 2016

Le Samouraï (Jean-Pierre Melville, 1967)

Was anyone, even Jean-Paul Belmondo, ever as cool as Alain Delon is in Le Samouraï? It's not just that he's beautiful, for beauty often works against men in the movies: They get classified as "pretty boys" and stuck in roles in which they're shown up by the more rough-hewn types. It's not just that he shows no emotion, or hardly ever; that could easily be mistaken for "limited acting range." It's not just that he wears clothes -- trenchcoat and carefully placed hat -- elegantly. It's not just that he's playing the movies' most evocative loner, the hit man, whose monomaniacal pursuit of his mission invokes a bit of paranoia in us all. Or that, in its 1960s context, the film echoes the rage against order that stirred youth revolt around the world. Or that he evokes the detachment of existentialist heroes like Meursault in Camus' The Stranger. It's all of these things, of course, but mostly it's that Jean-Pierre Melville, in script (co-written with Georges Pellegrin) and direction, is able to create the perfect atmosphere -- part detective story, part American film noir hommage, part romanticism -- around the character of Jef Costello -- even the name, with its missing "f" and its evocation of the Italian-American mobster Frank Costello, has a certain weird glamour. (The Italian release was called Frank Costello faccia d'angelo, i.e., "Frank Costello Angel Face.") Delon is the perfect choice for the role, emphasizing the absurdity of the premise that someone so striking in appearance could go about his bloody work unnoticed. The absurdity is of course intentional on Melville's part, making mock of the glamorizing of violence. Similarly, the title mocks the glamorizing of violence in samurai films -- not so much those of Kurosawa and Kobayashi as the less-prestigious entries in the genre. The mockery is, however, not malicious but affectionate, and only comic in retrospect. I don't know many other films who unfold themselves so remarkably upon reflection.

Sunday, December 4, 2016

Bringing Up Baby (Howard Hawks, 1938)

Although it's often called the greatest of all screwball comedies, to my mind Bringing Up Baby transcends that label: It's the finest example I know of a nonsense comedy. Screwball comedies like My Man Godfrey (Gregory La Cava, 1936) and Nothing Sacred (William A. Wellman, 1937) usually have one foot in the real world -- the Depression and its Hoovervilles in the case of the former, exploitation journalism in the latter. Bringing Up Baby exists only in a universe where an impossible thing like an "intercostal clavicle"* could exist. Its world is a place where nobody listens to anyone else and everyone seems to be marching to their own drummer. It's what puts Bringing Up Baby in the sublime company of Lewis Carroll's works or James Joyce's Finnegans Wake. Fortunately it's more accessible than the latter and at least as much fun as the former. Nonsense is harder to bring off on film than in literature. Cinema by nature is a documentary medium -- one that's assumed to be recording reality -- and has less flexibility than words do. It's also a collaborative medium, which means that everyone involved in writing, directing, and acting in it has to be on the same wave length, or the whole thing will collapse like a soufflé with too many cooks. That's why Bringing Up Baby is almost sui generis: The only other movies that approach the sublimity of its nonsense are some of the ones with the Marx Brothers or W.C. Fields. Even Howard Hawks once admitted that he thought he had gone too far in crafting a comedy with "no normal people in it." Nevertheless, the soufflé continues to rise, thanks in very large part to Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant, whose four movies together -- the other three were directed by George Cukor: Sylvia Scarlett (1935), Holiday (1938), and The Philadelphia Story (1940) -- seem to me to demonstrate a more potent teaming than the more iconic one of Hepburn with Spencer Tracy. And then there's the sine qua non of the screwball comedy, a supporting cast of character players like Charles Ruggles, Walter Catlett, Barry Fitzgerald, May Robson, and Fritz Feld. The screenplay was put together by Dudley Nichols and Hagar Wilde, from a magazine story by Wilde that Hawks bought and then with their help -- and doubtless much ad-libbing from the cast -- revised out of all recognition. I only hope that whoever came up with the phrase "intercostal clavicle," which Grant delivers with such delight in its rhythms, received a bonus.

*In case you've never thought to look it up, "intercostal" means "between the ribs" and usually refers to the muscles and spaces in the ribcage. The clavicle, or collarbone, sits atop the ribs and therefore can't be between them.

Saturday, December 3, 2016

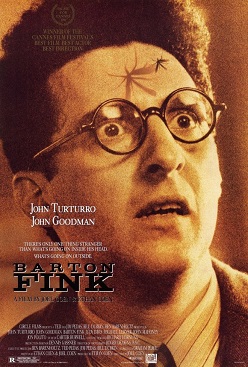

Barton Fink (Joel Coen and Ethan Coen, 1991)

The Coen brothers are nothing if not audacious, and attempting something so outrageous and anomalous as Barton Fink at the beginning of their careers -- it was their fourth feature, after Blood Simple (1984), Raising Arizona (1987), and Miller's Crossing (1990) -- shows a certain amount of courage. It's a curious melange of satire, horror movie, comedy, thriller, fantasy, and fable that had many critics singing its praises. It was their first film to receive notice from the Motion Picture Academy, earning three Oscar nominations: supporting actor Michael Lerner, art directors Dennis Gassner and Nancy Haigh, and costume designer Richard Hornung. And it was the unanimous choice for the Palme d'Or at the 1991 Cannes Film Festival; Joel Coen also won as best director and John Turturro as best actor. Evidently it took everyone by surprise. But I have to admit that although it's a provocative and unsettling movie, I don't much care for it. There's not enough of any one element in the melange to suggest to me that it's anything other than the work of a couple of extraordinarily talented writer-directors riffing on whatever comes to their minds. Barton (Turturro) is a playwright whose hit on Broadway in 1941 gets him a bid to come work in Hollywood. There, studio head Jack Lipnick (Lerner) assigns him to write a wrestling picture for Wallace Beery. Stymied in his attempt to come up with a screenplay, Barton decides to pick the brain of a famous novelist who has also come to work in Hollywood, W.P. Mayhew (John Mahoney). The playwright, the studio head, and the novelist are all caricatures of Clifford Odets, Louis B. Mayer, and William Faulkner, respectively. To my mind, this real-world reference point throws the film off center. Each caricature is well-done: What we see of Barton's play is a deft parody of the Odets-style leftist "little people" dramas like Waiting for Lefty and Awake and Sing! that Odets was known for. Lipnick is a rich, sentimental vulgarian with a mean streak, who like Mayer was born in Minsk. And Mayhew not only goes by the name "Bill," as Faulkner did among his friends and family, he also has a wife back home named Estelle, just as Faulkner did. Moreover, he is an alcoholic who is looked after in Hollywood by his mistress, Audrey Taylor (Judy Davis), who is clearly based on Faulkner's Hollywood mistress, Meta Carpenter. But then we have the turns into horror-fantasy when Barton tries to hole up in a Los Angeles hotel and makes friends with his next-door neighbor, an insurance salesman named Charlie Meadows (John Goodman). Good-time Charlie is later revealed to be a serial killer named Karl Mundt -- another of the Coens' in-jokes, I think: The real-life Karl Mundt was a right-wing dunce who represented South Dakota (neighbor state to the Coens' Minnesota) in Washington from 1939 to 1973. Clearly, Barton Fink is not without a certain baroque fascination to it. It's the kind of film you can spend hours analyzing and annotating. And this makes it, for me, little more than a fabulous mess.

Zootopia (Byron Howard and Rich Moore, 2016)

More evidence that this is a golden age for animation, especially with the perfecting of computer-animation techniques. But Zootopia's success lies as much in its story and its voice actors as in its technology. Actually, the success of the story is a bit of a surprise, considering that it was created by a committee and went through many alterations before settling on the central thread of a young rabbit, Judy Hopps (voice of Gennifer Goodwin), who wants to be a cop, and eventually teams up with a con-man fox, Nick Wilde (voice of Jason Bateman), to solve the mysterious disappearances of several residents of Zootopia, a place where predators and prey have learned to live together amicably. It seems that the disappeared were all predators who "turned feral" before they vanished. No fewer than seven credited writers -- and doubtless many more uncredited -- worked on the story before it was turned into a screenplay by Phil Johnston and Jared Bush (the latter also receives a credit as "co-director," whatever that means). Goodwin and Bateman are full of charm in their line delivery, and Idris Elba, as Judy's blustering and bellowing police chief, brings great energy to his role. Like so many recent computer-animated features, it is sometimes over-crowded with gags taking place on the periphery that it's possible to get a little distracted by them: a sure way of enticing people to watch the movie more than once.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)