A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Wednesday, December 21, 2016

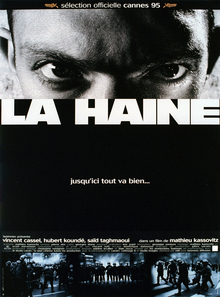

La Haine (Mathieu Kassovitz, 1995)

Would the friendship of the Jew, Vinz (Vincent Cassel), the African, Hubert (Hubert Koundé), and the Arab, Saïd (Saïd Taghmaoui) be possible in the Parisian banlieus today? For that matter, was it in fact possible when writer-director Mathieu Kassovitz made La Haine in 1995? Or was it a symbolic construct to emphasize solidarity against the Establishment and the corrupt police force, somewhat like the ethnic stews of Italian-, Irish-, and Jewish-Americans (but never, sadly, African-Americans) that Hollywood filmmakers put on bomber crews and destroyers during World War II as a way of promoting solidarity against the enemy powers? The question is rhetorical, of course, and not designed to undermine the importance and brilliance of Kassovitz's terrific (and terrifying) film, made in response to outbreaks of violent protest in the poorer suburbs of Paris. It has the quality of some of the best neo-realist Italian films of the postwar years, with the additional sense of something about to erupt that pervades the film and has not dissipated in the 21 years since it was made. If anything, it has spread into the rest of the world, especially in the post-9/11 era. The trio of actors on whom the film mainly focuses is extraordinary, both individually and as an ensemble.

Tuesday, December 20, 2016

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (Rouben Mamoulian, 1931; Victor Fleming, 1941)

MGM's 1941 Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is a virtual remake of Paramount's 1931 version of the Robert Louis Stevenson novella: John Lee Mahin's screenplay is clearly based on the earlier one by Samuel Hoffenstein and Percy Heath. The similarities are so obvious that MGM, having bought the rights to Paramount's version, tried to buy up all prints of it.* Seeing the two versions back-to-back is a pretty good lesson in how things changed in Hollywood over ten years: For one thing, the Production Code went into effect, which means that the "bad girl" Ivy (Miriam Hopkins in 1931, Ingrid Bergman in 1941) ceased to be a prostitute and became a barmaid. Hopkins shows a good deal more skin than does Bergman, and in the 1931 we see the scars on her back, inflicted by Hyde's whip, whereas in 1941 we see only the shocked reaction of those who witness them. As for Jekyll/Hyde (Fredric March in 1931, Spencer Tracy in 1941), the earlier version gives us a lustier Jekyll -- we sense that he's so eager to marry the virtuous Muriel Carew (Rose Hobart) because he wants to go to bed with her. Tracy's Jekyll indulges in a little more PDA with his fiancée, Beatrix Emery (Lana Turner), than her Victorian paterfamilias (Donald Crisp) would like, but there's no sense of urgency in his attraction to her. It's widely known that the original casting had Turner playing Ivy and Bergman as Beatrix, but that Bergman wanted to play the bad girl for a change -- it's clearly the better part -- and persuaded director Victor Fleming to make the switch. March's Hyde is a fearsome, simian creature with a gorilla's skull and great uneven teeth; Tracy's is just a man with a lecherous gaze, unruly hair, bushy eyebrows, and what looks like an unfortunately oversize set of false teeth. March's Jekyll -- pronounced to rhyme with "treacle" -- is a troubled intellectual, whereas Tracy's -- pronounced to rhyme with "heckle" -- is a genial Harley Street physician who genuinely wants to find a cure for bad behavior. March won an Oscar for his performance, and he does lose his sometimes rather starchy manner in the role. Tracy, I think, was just miscast, though in real life he had his own Jekyll/Hyde problems: The everyman persona hid a mean drunk.

*MGM did the same thing to Thorold Dickinson's 1940 film of Gaslight when it made its own version, directed by George Cukor, in 1944, but didn't succeed in either case.

Monday, December 19, 2016

The Jungle Book (Jon Favreau, 2016)

Fuddy-duddy that I am, I can't quite bring myself to approve of Disney's remaking the films it made with traditional cel animation, this time with a combination of live action and CGI. The new version of Beauty and the Beast (Gary Trousdale and Kirk Wise, 1991) is scheduled for next year, and I understand that a live-action remake of Mulan (Tony Bancroft and Barry Cook, 1998) is to follow. But some of my reservations were canceled by this version of The Jungle Book, a worthy remake of the 1967 cel-animated film directed by Wolfgang Reitherman -- one of the celebrated Nine Old Men at Disney -- which was also the last film Walt Disney supervised before his death. That version isn't generally regarded as in the first rank of Disney films anyway; it's mostly remembered for the peppy vocal performances of the songs "The Bare Necessities" and "I Wanna Be Like You" by Phil Harris and Louis Prima respectively. The new version dazzles with its creation of a credible CGI jungle filled with realistic CGI animals, and with some fine voiceover work by Bill Murray as the bear Baloo, Ben Kingsley as the panther Bagheera, Scarlett Johansson as the python Kaa, and especially Idris Elba as the villain, the tiger Shere Khan. It's remarkable to me that Elba, one of the handsomest and most charismatic of actors, has lately done work in which he's heard but not seen: He's also unseen in Zootopia (Byron Howard and Rich Moore, 2016). But then the same thing is true of the beautiful Lupita Nyong'o, whose voice is heard in The Jungle Book as the mother wolf Raksha, just as it was heard as the gnomelike Maz Kanata in Star Wars: Episode VII -- The Force Awakens (J.J. Abrams, 2015). Neel Sethi, this version's Mowgli, is the only live-action actor we see, and he displays a remarkable talent in a performance that took place mostly before a green screen -- puppets stood in for the animals before CGI replaced them. The screenplay by Justin Marks is darker than the 1967 film, and it successfully generates plausible actions for its realistic animal characters. But I think it was a mistake to carry over the songs from the original film, partly because Bill Murray and Christopher Walken (as King Louie, the Gigantopithecus ruler of the apes) are not the equal of Harris and Prima as singers, but also because the animals for which they provide voices are made to move rhythmically -- as a substitute for dancing -- in ways that don't quite suit realistic animals. Director Jon Favreau has also slipped in an allusion to Apocalypse Now (Francis Ford Coppola, 1979) in his introduction of King Louie, lurking in the shadows of a ruined jungle temple like Marlon Brando's Kurtz.

Sunday, December 18, 2016

The Lady From Shanghai (Orson Welles, 1947)

Like most of Orson Welles's Hollywood work, The Lady From Shanghai is the product of clashing wills: Welles's and the studio's -- in this case, Columbia under its infamous boss Harry Cohn. And as usual, the clash shows, sometimes in Welles's brilliance, such as the celebrated shootout in a hall of mirrors at the film's end, and sometimes in his indifference to the material: Is there any real excuse for the farcical courtroom scene that so violates any sense of consistency in the film's tone? Welles miscast himself as the protagonist, Michael O'Hara, a two-fisted Irish seaman, complete with an accent that he must have picked up in his youthful days in the Dublin theater. His soon-to-be ex-wife, Rita Hayworth, was forced upon him by Cohn, whom he angered by having her cut her hair and dye it blond. Her Elsa Bannister is the epitome of the treacherous film noir femme fatale, but it's hard to say whether the screenplay -- mostly by Welles -- or Hayworth's limited acting ability prevents the character from coming into focus. The real casting coup of the film is Everett Sloane as as Elsa's crippled husband, Arthur, and Glenn Anders as his partner, George Grisby. I use the word "partner" intentionally, because the film dodges around the Production Code in its hints that Bannister and Grisby are more than just law-firm partners, evoking the stereotypical catty and mutually destructive gay couple. Welles insisted on filming on location, which means we get some fascinating glimpses of late-1940s Acapulco and San Francisco, shot by Charles Lawton Jr. and the uncredited Rudolph Maté and Joseph Walker. In short, the movie is a mess, but sometimes a glorious mess.

Friday, December 16, 2016

The Lobster (Yorgos Lanthimos, 2015)

Thursday, December 15, 2016

Deadpool (Tim Miller, 2016)

Good nasty fun, and a fine example of having your cake and eating it too. By which I mean that, thanks to director Tim Miller, screenwriters Rhett Reese and Paul Wernick, and star Ryan Reynolds, Deadpool succeeds not only in sending up the destructive violence of comic-book superhero movies, but also in providing its own entertainingly destructive violence. Reynolds plays Wade Wilson, a former special forces op who, learning that he has cancer, submits to an experimental treatment that leaves him disfigured but invulnerable. And so it goes, as Wilson crafts a superhero costume to hide his disfigurement and calls himself Deadpool. (He takes his name from the "dead pool" run by his friend Weasel (T.J. Miller), who runs a bar whose regulars frequently get themselves into mortal scrapes and place bets on who'll get killed next.) No truth, justice, and the American way for Deadpool, whose chief aim is to get even with Ajax (Ed Skrein), who caused his disfigurement and claims to have a way of reversing it. The whole thing is an excuse for cynical wisecracks and the kind of destruction that in the usual superhero films is brought about by the fight against evil. In this case, Deadpool is only on the side of right by default: Ajax and his minions are so much worse. The film made a lot of money, surprising only those who thought that giving it an R rating -- for sex and naughty language as well as the usually more-tolerated violence -- would eliminate, or at least severely reduce, the supposed "core audience" for comic-book superhero movies: teenage boys. Deadpool does nothing to advance the art of film, but it still serves to expose the less idealistic side of superheroism.

Links:

Deadpool,

Ed Skrein,

Paul Wernick,

Rhett Reese,

Ryan Reynolds,

T.J.Miller,

Tim Miller

Wednesday, December 14, 2016

Salt of the Earth (Herbert J. Biberman, 1954)

|

| Striking miners in Salt of the Earth |

Sunday, December 11, 2016

Apocalypse Now (Francis Ford Coppola, 1979)

|

| Martin Sheen in Apocalypse Now |

Col. Kurtz: Marlon Brando

Lt. Col. Kilgore: Robert Duvall

Jay "Chef" Hicks: Frederic Forrest

Lance B. Johnson: Sam Bottoms

Tyrone "Clean" Miller: Laurence Fishburne

Chief Phillips: Albert Hall

Col Lucas: Harrison Ford

Photojournalist: Dennis Hopper

Director: Francis Ford Coppola

Screenplay: John Milius, Francis Ford Coppola, Michael Herr

Based on a novel by Joseph Conrad

Cinematography: Vittorio Storaro

Production design: Dean Tavoularis

Film editing: Lisa Fruchtman, Gerald B. Greenberg, Walter Murch

The familiar story of the confused and sometimes disastrous making of Apocalypse Now has been told many times, and never better than by Francis Ford Coppola's wife, Eleanor, in her 1991 documentary Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker's Apocalypse. So it's not worth going into here, except to note that the subtitle of her film plays on both the current meaning of the word "apocalypse" -- i.e., a disaster of great magnitude -- and the original one: a disclosure or revelation. It might be said that the enormous expenditure and hardship that Francis Coppola experienced during the making of Apocalypse Now was revelatory, not only to Coppola but also to the film industry, which was reaching the limits of its tolerance of unconstrained visionary filmmaking. It would cross that limit the following year with Heaven's Gate, Michael Cimino's film that took down a venerable production force, United Artists, along with its director. Coppola's career, unlike Cimino's, would recover, but he would never again be the director he was in his prime, with the first two Godfather films. And American filmmaking would never again be as prone to take risks as it was in the 1970s. As for the film itself, Apocalypse Now remains one of the essential American movies if only because it epitomizes the nightmare that was the Vietnam War. Coppola deserves much of the credit for this embodiment of Lord Acton's familiar dictum: "Power tends to corrupt. Absolute power corrupts absolutely." But there are others who should share the credit with him, including screenwriters John Milius and Michael Herr, who made the connection between Joseph Conrad's tale of imperialism gone wrong, Heart of Darkness, and the war. The ambience of the film is largely the work of production designer Dean Tavoularis, cinematographer Vittorio Storaro, who won a well-deserved Oscar, and Walter Murch and his sound team, who also won. And while Marlon Brando's Kurtz is a disappointment and Martin Sheen never quite meets the demands of his role as Capt. Willard, they are surrounded by marvelous support from Robert Duvall, Frederic Forrest, Dennis Hopper, and a very young and almost unrecognizable Laurence Fishburne (billed as Larry), among others.

Saturday, December 10, 2016

Die Nibelungen (Fritz Lang, 1924)

Die Nibelungen: Siegfried

|

| Hanna Ralph in Die Nibelungen: Siegfried |

Kriemhild: Margarete Schön

Brunnhild: Hanna Ralph

Siegfried: Paul Richter

King Gunther: Theodor Loos

Hagen Tronje: Hans Adalbert Schlettow

Mime / Alberich: Georg John

Die Nibelungen: Kriemhild's Revenge

|

| Margarete Schön in Die Nibelungen: Kriemhild's Revenge |

Queen Ute: Gertrud Arnold

King Gunther: Theodor Loos

Hagen Tronje: Hans Adalbert Schlettow

King Etzel: Rudolf Klein-Rogge

Slaodel: Georg John

Director: Fritz Lang

Screenplay: Fritz Lang, Thea von Harbou

Cinematography: Carl Hoffmann, Günter Rittau, Walter Ruttmann

Art direction: Otto Hunte, Karl Vollbrecht

Costume design: Paul Gerd Guderian, Aenne Willkomm

Music: Gottfried Huppertz

Fritz Lang's two-part epic, based on the Middle High German Nibelungenlied, will confuse anyone who knows the story only via Richard Wagner's Ring cycle: There are no Rhinemaidens or gods or Valkyries, nothing of Siegfried's parentage, and, since it lacks gods, consequently no Götterdämmerung. It consists of two films, Siegfried and Kriemhild's Revenge, that tell the story -- parts of which will be familiar from the final two operas in Wagner's cycle -- of how Siegfried slew the dragon and bathed in its blood, becoming invincible except for one spot on his back that the blood failed to touch, then killed the dwarf Alberich and took possession of a magic net that renders him invisible. He travels to Burgundy, where he wins the hand of the beautiful Kriemhild by helping her brother, King Gunther, subdue the warrior maiden Brunnhild. But Siegfried is killed after Gunther's advisor, Hagen, tricks Kriemhild into revealing his vulnerable spot. Brunnhild kills herself and Kriemhild vows revenge on the whole lot, which in the second film she accomplishes by marrying King Etzel, aka Attila, and provoking war between his Huns and the Burgundians. Lang tells the story with an eye-filling blend of tableaus, set-pieces, and scenes swarming with bloody action, concluding with a spectacular fire in which the Burgundians are trapped in Etzel's castle. The performances are pretty spectacular, too. Richter plays Siegfried as a muscular young goof ensnared by fate, Ralph is a formidable Brunnhild, and Schön modulates from naïve to terrifying as Kriemhild. But it's the production design by Otto Hunte and the costuming by Paul Gerd Guderian that lingers most in the memory. The production evokes late 19th- and early 20th-century book illustrators like Arthur Rackham and Walter Crane, but also the stark hieratic figures of Byzantine mosaics, especially Kriemhild, who becomes more powerfully static as the film progresses. Much has been written about the way the film fed into the heroic German myth that was co-opted by the Nazis, especially since the screenwriter, Thea von Harbou, Lang's wife at the time, later joined the party. (Lang, whose mother was Jewish, left Germany in 1934.) In fact, the Nazis sanctioned only the first half, Siegfried, after they came to power. Kriemhild's Revenge, with its depiction of the corruption of power and its nihilistic ending, didn't suit their purposes.

Friday, December 9, 2016

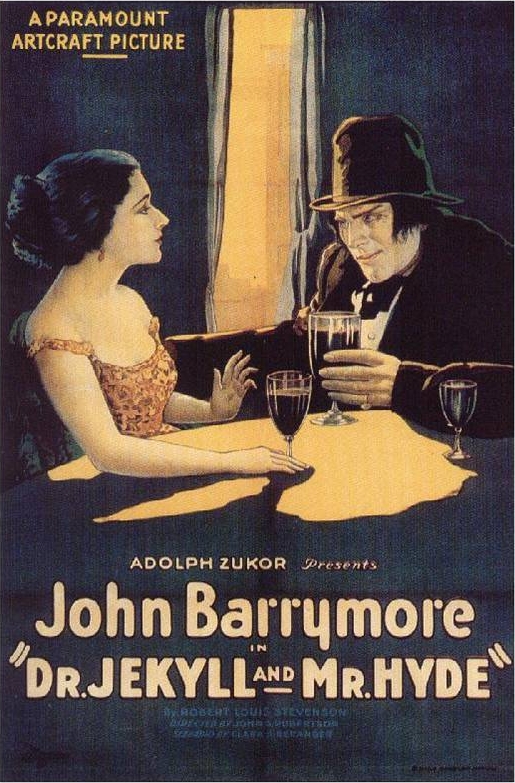

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (John S. Robertson, 1920)

Almost from the moment that Robert Louis Stevenson published his novella Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde in 1886, theatrical producers were snapping it up for adaptation. It was a great vehicle for ham actors who relished the transformation scenes, as long as it could be spiced up a little with a little sex -- the novella is more interested in the psychology of Jekyll/Hyde than in the lurking-horror and damsels-in-distress elements added to most stage and screen versions. There were several film versions before John Barrymore, the greatest of all ham actors, took on the role in 1920. It's an adaptation by Clara Beranger of the first major stage version by Thomas Russell Sullivan, who added a central damsel in distress as Jekyll's love. She's called Millicent Carewe (Martha Mansfield) in the film, which also adds a "dance hall girl" named Gina (Nita Naldi) to the mix. Mansfield is bland and Naldi is superfluous, though rather fun to watch when she goes into her "dance," which consists of a lot of hip-swinging and arm-waving. Barrymore, however, is terrific, giving his transformation into Hyde everything he's got in the way of contortions of face and body. Though the screenplay makes much of the distinction between the virtuous Jekyll and the dissolute Hyde, Barrymore manages to suggest the latency of Hyde in Jekyll even before he swallows the sinister potion -- a reversion to Stevenson's original, in which Jekyll is not quite the upstanding fellow the adaptations tried to make him.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)