A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Friday, February 3, 2017

Yi Yi (Edward Yang, 2000)

In his Criterion Collection essay on Yi Yi, Kent Jones does something that I endorse completely: He compares writer-director Edward Yang's film to the work of George Eliot. As I was watching Yi Yi, I kept thinking that it gave me the same satisfaction that a good novel does: that of participating in the lives of people I would never know otherwise. George Eliot's aesthetic was based on the premise that art serves to enlarge human sympathy. It's an idea echoed in the film by a character who quotes his grandfather saying that since the introduction of motion pictures, we now live three times longer than we did before -- we experience that many more things The remark in context is ironic, given that the character, a teenager (Pang Chang Yu) who will later commit a murder, mentions killing as one of the experiences now vicariously afforded to us by movies. But the general import of the observation stands: Yi Yi gives us the sweep of life, beginning with a wedding and ending with a funeral, and taking in along the way birth, found and lost love, and other experiences of the Jian family and acquaintances in Taiwan. The central character, N.J. (Nien-Jien Wu), is a businessman caught up in the machinations of his company while trying to deal with family problems: His mother-in-law suffers a stroke and lies comatose; his brother-in-law's wedding to a pregnant bride is interrupted by a furious ex-girlfriend; his wife has an emotional breakdown and leaves for a Buddhist retreat in the mountains; his daughter, Ting-Ting (Kelly Lee), is in the throes of adolescent self-consciousness and blames herself because her grandmother suffered a stroke while taking out the garbage Ting-Ting had been told to take care of; his small son, Yang-Yang (Jonathan Chang), refuses to join the family in taking turns talking to his comatose grandmother, and he keeps getting in trouble at school. And these matters are complicated by the reappearance of N.J.'s old girlfriend, Sherry (Sun-Yun Ko), now married to a Chicago businessman, who joins N.J. in Tokyo on a business trip that puts him at odds with his company. The separate experiences of N.J., Ting-Ting, and Yang-Yang overlap and sometimes ironically counterpoint one another, and the film is laced together by recurring images and themes. Although it's three hours long, Yi Yi never seems slack. A lesser director would have cut some of the sequences not essential to the narrative, such as the performances of Beethoven's "Moonlight" Sonata and the Cello Sonata No. 1, or the long pan across the lighted office windows in nighttime Taipei, but these give an essential emotional lift to a film that has rightly been called a masterwork.

Links:

Edward Yang,

Jonathan Chang,

Kelly Lee,

Nien-Jien Wu,

Pang Chang Yu,

Sun-Yun Ko,

Yi Yi

Thursday, February 2, 2017

The King of Kings (Cecil B. DeMille, 1927)

Director Cecil B. DeMille always had a fondness for unintentionally hilarious dialogue. Think of Anne Baxter's Nefretiri purring to Charlton Heston's Moses in The Ten Commandments (1956), "Oh, Moses, Moses, you stubborn, splendid adorable fool!" I'm almost sorry that The King of Kings is a silent film, so that we can't hear Mary Magdalene (Jacqueline Logan) utter the line: "Harness my zebras -- gift of the Nubian king! This Carpenter shall learn that he cannot hold a man from Mary Magdalene!" After the intertitle card fades, she swans off to rescue her lover, Judas Iscariot (Joseph Schildkraut), from the clutches of Jesus (H.B. Warner). It seems that Judas has become a disciple of Jesus because he believes that he has a chance at a powerful position in the new kingdom that Jesus is planning. This isn't the only hashing-up of the gospels that the credited scenarist, Jeanie Macpherson, commits, but it's the most surprising one. It also gives director DeMille an opportunity to introduce some sexy sinning before he gets pious on us: The Magdalene is vamping around a somewhat stylized orgy and wearing a costume (probably designed by an uncredited Adrian, who was good at that sort of thing) that leaves one breast almost bare. This opening sequence is also in two-strip Technicolor, as is the Resurrection scene some two and a half hours later. Yes, it's an enormously tasteless movie. Warner's Jesus is the usual blue-eyed blond in a white bathrobe found in vulgar iconography, and the actor has little to do but stand around looking wistful and sad at the plight of the world, occasionally giving a little smile that, with Warner's thin, lipsticked mouth, verges dangerously on a smirk. The film goes heavy on the miracles, even recasting one of the gospel writers, Mark, as a boy (Michael D. Moore) cured of lameness by Jesus. (When he throws away his crutch, it accidentally strikes one of the Pharisees standing nearby, only adding to their enmity to Jesus.) Unfortunately, DeMille stages the revival of Lazarus in a way that enhances its creepiness, having him emerge from a sarcophagus swathed in bandages like a horror-film mummy. Still, there's entertainment to be had, if you're not too demanding. Schildkraut's Judas is fun to watch at times: Once, he even skulks away like Dracula with his face hidden by his cloak. His father, Rudolph Schildkraut, plays the sneering high priest Caiaphas, Victor Varconi is a suitably conflicted Pontius Pilate, and William Boyd, soon to make his name as Hopalong Cassidy, is Simon of Cyrene, who helps Jesus carry the cross. The storm and earthquake after the Crucifixion is a DeMille-style special-effects extravaganza. The cinematography by J. Peverell Marley leans heavily on filters and screens to cast halos around Jesus, but does what it can to bring DeMille's characteristic tableau groupings to life. Fortunately, the movie also goes out of its way to avoid arousing antisemitism: The crowds calling for crucifixion are shown to be largely made up of bribed bullies who are suppressing those who want Jesus released, and one man furiously rejects the bribe by saying that as a Jew he cannot betray a brother.

Wednesday, February 1, 2017

An Inn in Tokyo (Yasujiro Ozu, 1935)

|

| Takeshi Sakamoto and Tomio Aoki in An Inn in Tokyo |

Otaka: Yoshiko Okada

Otsune: Choko Iida

Zenko: Tomio Aoki

Kuniko: Kazuko Ojima

Policeman: Chishu Ryu

Masako: Takayuki Suematsu

Director: Yasujiro Ozu

Screenplay: Masao Arata, Tadao Ikeda, Yasujiro Ozu

Cinematography: Hideo Shigehara

Does any filmmaker have a clearer, less sentimental view of the moral conundrum of childhood than Yasujiro Ozu? We tend to think that because children are innocent they are naturally good, when in fact their egotism leads them into trouble. In Ozu's I Was Born, But... (1932) and Good Morning (1959), the naive self-centeredness of children causes problems both for them and for their middle-class parents. Much the same thing happens in An Inn in Tokyo, one of Ozu's late silent films, but the consequences are more serious. Kihachi is a single father down on his luck, trudging the road through an industrial district in search of work, accompanied by his two small sons, Zenko and Masako. Kihachi is a loving father -- there's a wonderful scene in which he pretends to be drinking sake that Zenko is serving him, after which the boys pretend to eat the food they can't afford -- but perhaps a little too indulgent. The boys capture stray dogs which they turn in to the police because there's a small reward, part of a rabies-control effort. But when Zenko collects the reward, he spends it on a cap he has wanted, instead of the food and shelter they need. Later, when Kihachi goes to a job interview, he tells them to wait for him by the side of the road with the small bundle that contains all of their possessions. But after a while they decide to follow him, and squabble over which one is to carry the bundle. Zenko takes off, leaving his younger brother behind, but Masako abandons the bundle, and when they go back to retrieve it, it's gone. And when they are left with only enough money for either food or lodging for the night, Kihachi unwisely leaves the decision up to the boys, who naturally choose the immediate gratification of food -- leaving them out in the cold when it starts to rain. The film is often compared to the neo-realist films of Vittorio De Sica that were made more than a decade later, and it has the same graceful sensitivity to the plight of the underclass that De Sica's Bicycle Thieves (1948) demonstrates. Life improves for a while for Kihachi and the boys when he meets an old friend who helps him get a job. But in the end he is undone by his own kindness: He has met a young woman with a small daughter on the road, and when the little girl falls ill with dysentery, Kihachi resorts to theft in order to help her pay the hospital bills. In a heartbreaking ending, he turns himself in to the police. The performances are quietly marvelous, and while the existing restored print still shows the ravages of time, it's still possible to appreciate the cinematography of Hideo Shigehara, who collaborated frequently with Ozu in the pre-War period.

Tuesday, January 31, 2017

The Hateful Eight (Quentin Tarantino, 2015)

The title, The Hateful Eight, is pretty clearly an homage of sorts to such films as The Magnificent Seven (John Sturges, 1960), The Dirty Dozen (Robert Aldrich, 1967), and even The Wild Bunch (Sam Peckinpah, 1969). And it's well to remember how all of those films were once criticized for excessive violence and The Wild Bunch was once threatened with an NC-17 rating. None of them contained anything like the violence of The Hateful Eight, which is visited on all of the characters, but most memorably on the one woman among the eight: Daisy Domergue (Jennifer Jason Leigh), who is subjected to torrents of blood, vomit, and blown-out brains along with repeated blows to the face and a final drawn-out hanging. Writer-director Quentin Tarantino and his defenders excuse the excess of violence by arguing that his cinematic violence is a metaphor for racial and sexual violence in America and an expression of the revenge mentality that undermines the due administration of justice. As Oswaldo Mobray (Tim Roth) argues in the film, "dispassion is the very essence of justice. For justice delivered without dispassion is always in danger of not being justice." That Mobray is using this argument to forestall any actual dispassionate justice meted out to him only reinforces its irony -- a kind of postmodern irony that some will argue tends to lead us into spirals of self-defeat. That's why Tarantino's films often feel so nihilistic, despite their wit and technical prowess. At more than three hours, The Hateful Eight is about an hour too long, which I think is a fatal flaw, considering that the suspense lags as the slow revelation of its plot twists emerges. The wait for the eruptions of violence that we know are coming produces a kind of prurience, but there is no cathartic release when they arrive. The movie is well-acted by Leigh, Roth, Samuel L. Jackson, Kurt Russell, Walton Goggins, Demián Bichir, Bruce Dern, and Michael Madsen as the eight, and Channing Tatum gives a remarkable performance in his late surprise appearance. The music by Ennio Morricone won a well-deserved, long overdue Oscar, and the cinematography by Robert Richardson makes the most of the shift from spectacular mountain scenery to the claustrophobic setting of the major part of the film. But Tarantino has settled into predictability, and I want him to show us something new.

Monday, January 30, 2017

Mulholland Dr. (David Lynch, 2001)

Mulholland Dr. defies exegesis like no other film I know. Sure, you can trace its origins: Car-crash amnesia is a soap-opera trope; the mysterious mobsters and other manipulators are film noir staples; the portrayal of Hollywood as a nightmare dreamland is straight from Sunset Blvd. (Billy Wilder, 1950), which the film even imitates by having its before-the-credits title appear on a street sign. But writer-director David Lynch isn't out to parody the sources -- not entirely, anyway. What he is up to is harder to pinpoint. There's a part of me that thinks Lynch just wants to have fun -- a nasty kind of fun -- manipulating our responses. At the beginning, we're on to him in that regard: We laugh at the minimal conversation between the two detectives (Robert Forster and Brent Briscoe) at the crash site. We recognize the naive awe on the face of Betty Elms (Naomi Watts), as she arrives in Los Angeles, as a throwback to the old Hollywood musicals in which choruses of hopefuls arrive at the L.A. train station singing "Hooray for Hollywood!" (Has anyone ever been inspired to sing and dance when arriving at LAX?) We're delighted by the appearance of Ann Miller as the landlady, just as later we identify Lee Grant, Chad Everett, and even Billy Ray Cyrus in their cameos. Even the seemingly disjointed scenes -- the director, Adam Kesher (Justin Theroux), is bullied by the Castiglianes (Dan Hedaya and the film's composer, Angelo Badalamenti), or a man (Patrick Fischler) recounts his nightmare at a restaurant called Winkie's, or a hit man (Mark Pellegrino) murders three people -- are standard thriller stuff, designed to keep us guessing -- though at that point, having seen this sort of thing in films by Quentin Tarantino and others, we feel confident that everything will fit together. And then, suddenly, it doesn't. Betty vanishes and Diane Selwyn (Watts), whom we have thought dead, is alive. The amnesia victim known as Rita (Laura Harring) is now Camilla Rhodes, the movie star that Betty wanted to be, and Diane, Camilla's former lover, wants to kill her. It's such a complete overthrow of conventional narrative that there are really only two basic responses, neither of them quite sufficient: One is to dismiss the film as a wacked-out experiment in playing with the audience -- "a load of moronic and incoherent garbage," in the words of Rex Reed -- or to try to assimilate it into some coherent and consistent scheme, like the theory that the first two-thirds of the film are the disillusioned Diane Selwyn's dream-fantasy of what her life might have been as the fresh and talented Betty. There is truth in both extremes: Lynch is playing with the audience, and he is portraying Los Angeles as a land of dreamers. But his film will never be forced into coherence, and it can't be entirely dismissed. I think it is some kind of great film -- the Sight & Sound critics poll in 2010 ranked it at No. 28 in the list of greatest films of all time -- but I also think it's self-indulgent and something of a dead end when it comes to narrative filmmaking. It has moments of sheer brilliance, including a performance by Watts that is superb, but they are moments in a somewhat annoying whole.

Sunday, January 29, 2017

A Serious Man (Joel Coen and Ethan Coen, 2009)

|

| Michael Stuhlbarg in A Serious Man |

Uncle Arthur: Richard Kind

Sy Abelman: Fred Melamed

Judith Gopnik: Sari Lennick

Danny Gopnik: Aaron Wolff

Sarah Gopnik: Jessica McManus

Rabbi Marshak: Alan Mandel

Don Milgram: Adam Arkin

Rabbi Nachtner: George Wyner

Mrs. Samsky: Amy Landecker

Director: Joel Coen, Ethan Coen

Screenplay: Joel Coen, Ethan Coen

Cinematography: Roger Deakins

Production design: Jess Gonchor

Music: Carter Burwell

Joel and Ethan Coen's A Serious Man is a mordant tragicomedy that was surprisingly nominated for a best picture Oscar, edging out films like A Single Man (Tom Ford), Julie & Julia (Nora Ephron), Bright Star (Jane Campion), Fantastic Mr. Fox (Wes Anderson), and my own preference, About Elly (Asghar Farhadi). Perhaps the Coen brothers were still coasting on the acclaim and the Oscars they received for No Country for Old Men (2007), but A Serious Man seems to me a decidedly lesser work, too dependent on comic Jewish stereotypes -- the pot-smoking kid studying for his bar mitzvah, the sister saving for a nose job, the feckless uncle who hogs the bathroom, and so on. The protagonist, Larry Gopnik, is a lesser, latter-day Job, whose "comforters" include some preoccupied, cliché-spouting rabbis whom Larry seeks out as he tries to deal with his troubles: His wife wants a divorce so she can marry a widowed family friend, Sy Abelman; his freeloading brother Arthur keeps getting in trouble with the police; his bid for tenure as a physics professor is threatened by a student -- a stereotyped Asian -- who tries to slip him an envelope full of cash so Larry will change his grade; a gentile neighbor seems to be displaying passive-aggressive hostility; a provocatively sexy neighbor sunbathes naked while Larry is on the roof trying to adjust the TV antenna, and so on. He is plagued with nightmares in which all of these figures combine to torment him. The Coens seem to regard all of this as a kind of parable: They begin the film with their version of a Jewish folktale involving a man, his wife, and a dybbuk, and they end it with an approaching tornado -- is God going to speak out of the whirlwind? But the result, especially given the setting in 1960s suburbia, feels more like imitation Philip Roth. There's a lot to admire in the film, including Roger Deakins's cinematography, and some of the theological issues it raises are worth raising, but it left me with a sour feeling.

Saturday, January 28, 2017

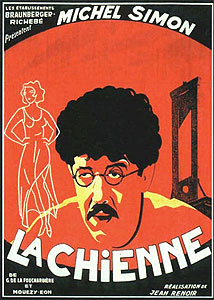

La Chienne (Jean Renoir, 1931)

Seeing Michel Simon as the milquetoast Maurice Legrand in La Chienne after L'Atalante (Jean Vigo, 1934) and Boudu Saved From Drowning (Jean Renoir, 1932) is something of a revelation, even if at the end of La Chienne he has become something like Boudu. But the entire film is a revelation: The second sound film by Renoir, it demonstrates an innovative mastery of what was essentially a new medium, one that even the Americans who claimed to have invented synchronized sound were still struggling with. Renoir -- with the help of sound technicians Denise Batcheff and Marcel Courmes -- creates an auditory ambience still rare in 1931, relying on dialogue and sound effects created on set and not in post-production. The most often-cited example is the rasp of the paper knife held by Lulu (Janie Marèse) as she cuts the pages of the book she's trying to read -- just before Legrand kills her with it. But the film is full of small auditory details like the squeaking of the shoes worn by the defense attorney (Sylvain Itkine) as he paces nervously back and forth before his doomed client, Dédé (Georges Flamant). But beyond the technical mastery, which also includes some brilliant camerawork by cinematographer Theodor Sparkuhl, the film is a tour de force of bitter irony, not least because Renoir keeps it from falling into sensationalism or unrelieved darkness. Legrand, initially the henpecked husband to a termagant (Magdeleine Bérubet), brings calamity to several lives, not only those of Lulu and Dédé, but also those of his wife and her supposedly dead ex-husband (Roger Gaillard). And yet, at the film's end he survives, not only unbroken but in many ways a stronger man than he was at the film's beginning. His story is framed as a puppet show with, as a puppet claims, "no moral message." But though Legrand commits fraud, adultery, and murder without receiving the official punishment of the law, the moral is aimed at those who scorned and abused him: Beware the worm who may turn and prove to be a viper.

Friday, January 27, 2017

Young and Innocent (Alfred Hitchcock, 1937)

If Alfred Hitchcock hadn't made The 39 Steps (1935) before Young and Innocent, the latter film might be taken for a somewhat less tightly plotted and certainly less well-cast sketch for the earlier one. Instead of Robert Donat as the man wrongly accused of murder on the run with Madeleine Carroll as his reluctant accomplice, we get the considerably lower-wattage Derrick De Marney and Nova Pilbeam. Young and Innocent (released in America as The Girl Was Young) feels almost like a retread, in which Hitchcock is trying out a few things that he'll use with more finesse in later films but isn't concerned with much in the way of plausibility and motivation. There is, for example, the focus on the hands when Erica Burgoyne (Pilbeam) is trapped in a car that's sliding into a sinkhole, and Robert Tisdall (De Marney) reaches out to grasp her. We'll see it again with variations in Saboteur (1942) and North by Northwest (1959), but there with more integration into the plot; here the sinking car seems to be only a gimmick introduced to allow Hitchcock to play with suspense-building techniques. There's also a long tracking crane shot that gradually focuses in on the villain (George Curzon) with a give-away tic that anticipates the tracking shot in Notorious (1946) that ends up on the key in Ingrid Bergman's hand. Hitchcock also uses Young and Innocent to exploit his well-known fear of the police, this time by mocking them, as when two cops are forced to hitch a ride with a farmer hauling livestock in his cart: When they complain about how crowded the cart is, the farmer tells them it was only built for ten pigs. Otherwise, Young and Innocent is agreeably nonchalant about plot essentials: Why was Tisdall mentioned in the murdered woman's will? Why did everyone assume that when he ran for help after discovering her body he was actually fleeing the scene of the crime? Why does he flee from the courtroom instead of sticking around to plead his case? Why does Erica so swiftly believe in his innocence? The film is nonsense, but it's enjoyable nonsense if you turn off such questions and go along for the ride. The screenplay, loosely based on a novel by Josephine Tey, is credited to Charles Bennett, Edwin Greenwood, and Anthony Armstrong, but I suspect it was much reworked by Hitchcock and his wife, Alma Reville, who is credited with "continuity," to allow for the director's experiments in suspense.

Thursday, January 26, 2017

Talk to Her (Pedro Almodóvar, 2002)

|

| Javier C'amara, Leonor Watling, Rosario Flores, and Dario Grandinetti in Talk to Her |

Wednesday, January 25, 2017

Umberto D. (Vittorio De Sica, 1952)

Umberto D. is sometimes grouped with Shoeshine (Vittorio De Sica, 1946) and Bicycle Thieves (De Sica, 1948) as the completing element in a trilogy about the underclass in postwar Rome. Shoeshine could be said to be a film about youth, Bicycle Thieves about middle age, and Umberto D. about old age. All three were directed by De Sica from screenplays by Cesare Zavattini that earned the writer Oscar nominations. Although Umberto D. is unquestionably a great film, it also seems to me the weakest of the three, largely because De Sica and Zavattini can't fully avoid the trap of sentimentality in telling a story about an old man and his dog. Umberto D. also relies too heavily on its score by Alessandro Cicognini to tug on our heartstrings. These flaws are mostly redeemed by the great sincerity of the performances, particularly by Carlo Battisti as Umberto, but also by Maria Pia Casilio as the pregnant housemaid, and Lina Gennari as Umberto's greedy landlady. Battisti, a linguistics professor who never acted before or after this film, is the perfect embodiment of the crusty Umberto Domenico Ferrari, a retired civil servant living on a pension that's inadequate to his needs. We're told that he has "debts," which include back rent to the landlady. He has no family except his dog, a small terrier called Flike, whom he dotes on, and no friends except for the housemaid, whose plight, since she's pregnant by one of two soldiers who have no intention of marrying her, is not much better than his. The film is most alive when it follows these characters on their daily rounds: the maid getting up in the morning and starting her daily chores, which include a continuing battle against the ants that infect the flat, and Umberto walking Flike, encountering old friends who carefully avoid noticing his plight or helping him out of it. He's too proud to beg and unwilling to go into a shelter because he would have to abandon Flike. In the end, he is forced out of the flat by the landlady, and wanders into a park where he tries to give Flike away to a little girl who has played with him there before. Her nursemaid, however, refuses to consider it -- dogs are dirty, she says. In a desperate moment, he picks up Flike, ready to stand in front of an oncoming train and die with him on the railroad tracks, but the dog panics, squirms out of his arms, and runs away. The film concludes with Umberto, having regained Flike's confidence, playing with the dog, their future still uncertain. The inconclusiveness of the final scene helps reduce the sentimentality that has flooded the sequence and focus our attention on Umberto's plight, rather than gratify our desire for closure.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)