|

| Kinuyo Tanaka and Ureo Egawa in Where Now Are the Dreams of Youth? |

A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Sunday, May 7, 2017

Where Now Are the Dreams of Youth? (Yasujiro Ozu, 1932)

Friday, May 5, 2017

Wings (Larisa Shepitko, 1966)

Wings was the first feature by Larisa Shepitko, who made only four of them before dying in an automobile accident in 1979, only 41. I've now seen two of her films, the other being her last completed one, The Ascent (1977), and it's clear to me how great a loss her death was. That last film was an extraordinary, harrowing adventure with a brilliant documentary realism but also a profound symbolic resonance. Her first is almost a polar opposite: a low-key character study of a woman whose adventures -- she was a decorated pilot during World War II -- are long behind her. Nadezhda Petrukhina (Mayya Bulgakova) now leads a quiet existence as headmistress of a school that prepares students for work in the construction industry. She is admired by her colleagues and students but unfulfilled by her work. She has an adopted daughter, Tanya (Zhanna Bolotova), but they have grown apart: Nadezhda hasn't even met Tanya's new husband, and when she goes to a party where he's present she mistakenly greets the wrong man as her son-in-law. In addition to supervising repairs at the school and coaching the participants in the school's entry in a theatrical contest, she also has to discipline a rebellious young male student -- with whom, we see, she has a kind of sympathy that is stifled by her official duties. She occasionally sees a man, the director of the local museum where her picture as a war hero is on display -- on a visit to the museum she overhears a girl ask if she's still alive. And occasionally she visits the local airfield to watch cadets being trained. We get a flashback to wartime, when she had a lover, Mitya (Leonid Dyachkov), a fellow pilot whose death in combat she witnessed. Flight, that eternal symbol of freedom, is a strong force even in the earthbound life she leads, and we glimpse her fantasies of soaring through the clouds. So at the film's end, having quit her job, she takes a daring move to achieve that freedom once again. Spare but poetic, with a stunning performance by Bulgakova, Wings was written by Valentin Ezhov and Natalya Ryazantseva and filmed by Igor Slabnevich.

Thursday, May 4, 2017

Ashes and Diamonds (Andrzej Wajda, 1958)

|

| Ewa Krzyzewska and Zbigniew Cybulski in Ashes and Diamonds |

Krystyna: Ewa Krzyzewska

Szczuka: Waclaw Zaztrzezynski

Andrzej: Adam Pawlikowski

Drewnowski: Bogumil Kobiela

Portier: Jan Ciecierski

Director: Andrzej Wajda

Screenplay: Jerzy Andrzejewski, Andrzej Wajda

Based on a novel by Jerzy Andrzejewski

Cinematography: Jerzy Wójcik

Production design: Roman Mann

The plot of Ashes and Diamonds is simple: A group of men carry out an ambush on a road in the countryside only to discover that their intended target was not among the men they killed. So they return to town to plot another way of assassinating the man. The youngest, most volatile member of the group discovers that the man has taken the room next door in the hotel, but while waiting for his opportunity, his flirtation with a pretty young woman turns serious -- they begin to fall in love. Still, renouncing that chance at happiness, he follows through with his mission: He kills the man, but before he can make his escape from the town he is gunned down. It could have been -- probably has been -- the plot of a Western, a gangster film, a spy thriller, or a war movie. But because it's a film made in Poland during the Cold War, and the story it tells is set on the very day in 1945 when the Germans surrendered, it's an intensely political film, not just in what's on the screen but also in what went on while it was being made and released. I mention this because while I want to think about movies in purely aesthetic terms -- i.e., assessing the quality of acting, writing, direction, camerawork, etc. -- it's almost impossible to approach a film like Ashes and Diamonds without taking so-called "external" factors like politics and history into consideration. If you try to watch it without knowing anything about the political situation in Poland in 1945, with the Germans retreating, the Soviets advancing, you'll miss half of the motivation of the characters and most of the intensity of the conflict. And if you disregard the fact that Poland in 1958 was a communist country, you can't understand why the plot to kill a communist leader was such a touchy subject for Andrzej Wajda to handle in a film -- and why the way he handled it was so audacious. It's a film that asks you to do your homework. On as pure an aesthetic level as I can get in thinking about the film, it's visually fascinating, with some splendid deep-focus cinematography by Jerzy Wójcik that pays homage to Gregg Toland's work on Citizen Kane (Orson Welles, 1941). Wajda was quite open about the influence of Welles on his filmmaking -- like Welles, Wajda wanted sets to have ceilings -- but he also expressed a love of American gangster movies and film noir, citing Scarface (Howard Hawks, 1932) and The Asphalt Jungle (John Huston, 1950) among his inspirations for Ashes and Diamonds. The American influence is probably most felt by viewers today in the performance of Zbigniew Cybulski in the role of Maciek, the young assassin. It's a showy, jittery, almost over-the-top performance that validates Cybulski's reputation as "the Polish James Dean." Wajda initially resisted casting Cybulski, wanting a more traditional actor for the role, but once Jerzy Andrzejewski, his co-screenwriter and author of the novel on which the film was based, persuaded him to hire Cybulski, Wajda realized that the handsome young star would attract the younger audience the film not only needed to succeed, but also to educate this audience about their country's past. He even gave in to Cybulski's demand that he be allowed to supply his own wardrobe -- not at all the kind of clothes that a young Polish partisan would have worn in 1945 -- including his signature sunglasses. (A line was inserted to explain that Maciek wore them because he had damaged his eyesight by spending too much time in the sewers of Warsaw during the uprising of 1944.) But Wajda added some idiosyncratic touches of his own to the film, including the bullets setting fire to the jacket of one of the unintended victims of the ambush, and some ventures into symbolism like the upside-down crucifix that looms over Maciek and Krystyna when they visit a ruined church and the white horse that wanders the streets of the town near the film's end. Maciek is shot in a field where white sheets are drying on clotheslines, and when he clutches one of the sheets to himself, his blood shows through -- even though the film is in black and white, this is a reminder that the colors of the Polish flag, like the one the hotel keeper takes out to wave at the film's end, are white and red. Wajda also delighted in the ambiguity of Maciek's death scene, one of Cybulski's most extravagant moments, which takes place on a garbage heap. For the communist censors, he observed, this could be interpreted as the fate of rebels against their rule, while young would-be rebels could see it as the state treating them as garbage.

Wednesday, May 3, 2017

X-Men: Apocalypse (Bryan Singer, 2016)

Oscar Isaac is one of my favorite actors. I loved his work in Inside Llewyn Davis (Joel and Ethan Coen, 2013), A Most Violent Year (J.C. Chandor, 2014), Ex Machina (Alex Garland, 2015), and on the HBO miniseries Show Me a Hero (2015). He even managed to stand out in all the whiz-bang and nostalgia of the latest Star Wars installment. But I sat through the entirety of X-Men: Apocalypse without realizing, until his name appeared in the credits, that he was the one beneath all the makeup and prosthetics as En Sabah Nur, aka Apocalypse. Which makes me wonder: Why bother? Casting an actor of such skill and versatility in a role that could have been played by anyone willing to sit through hours of applying and removing body paint, silicone, and foam latex seems to me a waste of valuable resources. But I guess the same thing could be said about the entire film if you ignore the return the producers got on their estimated $178 million investment. When a film this size feels routine, something has gone awry, and X-Men: Apocalypse is nothing if not routine. There are things I enjoyed about it, like the special effects when Quicksilver (Evan Peters) rescues almost everyone from the explosion that destroys the institute. The trick of seeing everything as Quicksilver sees it -- i.e., as time standing still while he moves at superspeed, dashing from room to room to haul occupants to safety -- is nicely done. And there are good performances from Peters, from James McAvoy as Charles Xavier, Michael Fassbender as Erik Lehnsherr, Jennifer Lawrence as Raven, Nicholas Hoult as Hank McCoy, and Kodi Smit-McPhee as Nightcrawler. I enjoyed seeing Sophie Turner (as the latest iteration of Jean Grey) in something other than Game of Thrones and Hugh Jackman in an unbilled (and extremely violent) cameo as Logan/Wolverine. But there's a kind of heartlessness and thoughtlessness about it, too often characteristic of the superhero blockbuster movie genre, that my experience amounted to a kind of déjà vu. I just hope Isaac got paid well.

Tuesday, May 2, 2017

L'Argent (Robert Bresson, 1983)

When does style become mannerism? And why is it that style is generally thought of as a good thing, and mannerism is often a pejorative? I found myself pondering these questions while watching Robert Bresson's last film, L'Argent. Bresson is one of the directors I most admire, so my first impulse is to admire L'Argent as a superb example of Bresson's austere style: his willingness to let the audience decide what's going on within the characters by restraining his actors' displays of emotion, the simplicity of his mise-en-scène, his use of ambient sound to do the job that other directors rely on musical scores to accomplish. He has a fascinating premise to explore in L'Argent, which he adapted from a story by Tolstoy: the horrible repercussions of the passing of a counterfeit bill by some schoolboys. They spend the bill in a photography shop, buying a picture frame mainly to get some real money in change. When the fake bill is discovered, the shop owner passes it off in payment to Yvon (Christian Patey), the young driver of a heating-oil delivery truck. When Yvon is arrested for passing counterfeit money, he identifies the clerk at the photography shop, Lucien (Vincent Risterucci), who gave him the money. But Lucien perjures himself, saying he had never seen Yvon before, so Yvon is convicted. Though he's given a suspended sentence, he loses the job that he needs to support his wife and small daughter. Unable to find work, he agrees to act as the getaway driver for an acquaintance who's robbing a bank, but is caught and thrown into prison. Life in prison does him no good, especially after he learns that his daughter has died of diphtheria and his wife has decided to start a new life. When he lashes out at a fellow inmate he is thrown into solitary. He attempts suicide, but survives and returns to prison where he finds that Lucien is also an inmate, having robbed the photography store and become rich through various forms of larceny. Embittered, Yvon serves out his term and is released, but he continues his descent into criminality, murdering the keepers of a small hotel and robbing them, and finally finding shelter with an elderly woman (Sylvie Van den Elsen), whom he also murders, along with her entire household. At the end, he confesses and is returned to prison. Bresson's dry, understated telling of this story gives it a kind of dreamlike matter-of-factness that a more florid and violent version couldn't achieve. But there are also moments when you become aware of the way Bresson is telling the story, moments in which, I think, style becomes mannerism, especially if you've seen enough Bresson films to recognize his particular way of dramatizing events. For example, there is one scene in which the camera focuses on a passageway in the Paris Métro: What we see for a long time (perhaps only seconds, but it feels longer given our natural impatience to want things to happen in a movie) are the foot of a stairway, the concrete floor and tiled walls, and the beginning of a passageway to the trains. Bresson holds on this empty space as we hear the train arrive and the doors open and people make their way toward the space, through it, and up the stairs past us. He stays on the space until people -- they are Lucien and two of his friends -- come down the stairs past us and enter the passage. We hear the train doors close and the train depart, and only then does Bresson cut to the platform and the train entering the tunnel. It's a moment of no real narrative importance, but Bresson's holding us there as it happens crafts a kind of suspense, a kind of anxiety of the quotidian that informs the entire film. The only problem I have with the scene is the way it sticks in my memory as an inflection of style. And remembering this moment at the expense of others more important to the theme and narrative of L'Argent makes me think of it as mannered. While it's still a fascinating and challenging film, Bresson's deadpan actors and his focus on emptiness lend themselves easily to caricature and parody, and I think he carries them too far in L'Argent, never finding the balance that make his masterworks -- Diary of a Country Priest (1951), A Man Escaped (1956), Au Hasard Balthazar (1966) -- such essential films.

Monday, May 1, 2017

Bridge of Spies (Steven Spielberg, 2015)

It goes without saying that Steven Spielberg is one of the great directors, with a seldom-equaled skill at visual storytelling and at building tension and suspense. But Spielberg tries too hard to make a statement in Bridge of Spies -- something about defending the Constitution -- when it could have been simply an engaging film about Cold War tensions. It also suffers from the wrong kind of star power: Tom Hanks has devolved from a terrific actor, skilled at both comedy and drama, into the movies' iconic Good Guy. Casting him as the lawyer James Donovan, forced to defend a Soviet spy, deprives the film of any ambiguity about Donovan's defense of Rudolf Abel (Mark Rylance). Hanks's Donovan can simply wrap himself in the Constitution and we're with him all the way, even as public opinion of the time turns against him. As a film actor Hanks has lost his dark side, so we know that whoever he plays will triumph. Imagine Bridge of Spies with Donovan played by George Clooney or Bradley Cooper, stars with just a touch of shadow in their personae, and you can see what I mean. Fortunately, the film is otherwise well-cast, including Rylance's Oscar-winning turn as Abel, as well as Scott Shepherd's impatient CIA man and Sebastian Koch's duplicitous East German lawyer, and the screenplay by Matt Charman and Joel and Ethan Coen manages a good deal of suspense. (Sometimes at the expense of historical accuracy: Donovan was never shot at in his home, as the film has it.) The Coen brothers were brought in to work on the first draft of Charman's screenplay, specifically on the section in which Donovan finds himself negotiating separately with the Soviets and the East Germans to engineer an exchange of Abel for imprisoned U2 pilot Francis Gary Powers (Austin Stowell) and an American student, Frederic Pryor (Will Rogers), who has been accidentally arrested in East Berlin. It's the best part of the movie, as Donovan wrangles not only with the conflicting egos and bureaucracies of the Soviet and East German officials but also with the CIA's insistence that only Powers need be included in the deal. Unfortunately, Spielberg doesn't know when his movie is over. Bridge of Spies should end with the exchange of spies at the bridge, but Spielberg keeps it running as Donovan boards the plane for home, returns to the arms of his family just as the news of his successful negotiation is breaking, gives his wife (Amy Ryan) the jar of marmalade he promised to bring her from London, witnesses her realization that he wasn't in London after all, and soon afterward rides to work on the bus where a woman who had previously frowned at him as a traitor now smiles at him as a hero after seeing his picture in the newspaper. All the while, Thomas Newman's score is telling us what we're supposed to feel. It's sheer sentimental anticlimax, of the sort that many critics decry in what are usually regarded as Spielberg's greatest films, Saving Private Ryan (1998) and Schindler's List (1993). (I happen to agree that the frame story of the aging Ryan's visit to the cemetery in Normandy is unnecessary, though I think the Yad Vashem sequence at the end of the latter film can be justified by the enormity of its subject matter.) Bridge of Spies is by no means a bad movie, but it would have been a lot better if Spielberg hadn't given in to his instinct for overemphasis.

Sunday, April 30, 2017

Il Posto (Ermanno Olmi, 1961)

|

| Loredana Detto and Sandro Panseri in Il Posto |

Domenico Cantoni: Sandro Panseri

Psychologist: Tullio Kezich

Domenico's Older Co-worker: Mara Revel

Director: Ermanno Olmi

Screenplay: Ermanno Olmi

Cinematography: Lamberto Caimi

Production design: Ettore Lombardi

Film editing: Carla Colombo

Music: Pier Emilio Bassi

Kafka was a realist. Anyone who has ever worked for a large, bureaucratic corporation knows this. Being pushed about, subjected to irrational rules and decrees, unable to do more in the face of injustice than simply duck and cover -- these are the facts of corporate life that echo throughout the stories of the former employee of the Workers Accident Insurance Institute in Prague. Ermanno Olmi's Il Posto (i.e. "the job") isn't really based on Kafka, though I suspect Olmi may have been familiar with his work, because the frustration that the film's young protagonist, Dominico Cantoni, runs up against has a striking resemblance to the arbitrary barriers that prevent Kafka's characters from making a break toward freedom. But Il Posto is also clearly under the influence of something Olmi certainly knew firsthand: Italian neorealism. Like Vittorio De Sica and Roberto Rossellini, Olmi works largely with non-professional actors in Il Posto -- on IMDb, Panseri has only two more credits and a note that he was a supermarket manager in Milan -- and the streets of Milan and its suburb of Meda are its principal setting, neither of them the beneficiary of any attempts at sprucing up and glamorizing. The human milieu of Il Posto is the office workers of the lower middle class, people who see a chance at lifetime employment with a big company as salvation from downward mobility. Domenico has left school to help support his family -- father, mother, and younger brother -- and the possibility of landing a job with the unnamed company looks like a godsend. So he rides the train into Milan and goes through a series of tests, including absurd physical and psychological exams obviously designed by someone with just enough knowledge to be a nuisance. On his lunch break, he meets a fellow job applicant, the pretty Antonietta (Loredana Detto became Olmi's wife two years later), and he's pleased to find, a few days later, that they've both been hired. Unfortunately, they have jobs in different parts of the company and their lunch hours don't mesh, so for the rest of the film they are unable to further their relationship. When they do manage to meet, Antonietta tells him about an employees' New Year's Eve party, which he attends only to find that she hasn't shown up. Though no clerical position is immediately available, Domenico is taken on as a messenger between departments, a job that mostly consists of sitting at a small table with his supervisor and waiting. Meanwhile, we meet some of the older employees, most of whom spend their days in the tiny office into which their desks have been crammed dozing, doing busywork, or getting chewed out for being late. Olmi takes a striking departure from Domenico's story to show us snippets of the after-hours lives of these employees, supplying a backstory that keeps them from just being caricatures. Then one of this group dies, and Domenico is promoted to his job. But when he arrives at the man's desk, it's being cleared out and another employee protests that this desk, at the front of the room, should go to someone with seniority. So when it's ready, there's a mad rush to claim it, leaving Domenico in the poorly lighted back of the room. The film ends with a closeup on his face as a mimeograph machine clacks away. He says and does nothing, but when we reflect that the young man has just seen what's involved in attaining a position that will last for the rest of his life, we can imagine his feelings. Il Posto is a small film but a brilliant one that brings to mind more celebrated films about corporate life, such as The Crowd (King Vidor, 1928) and The Apartment (Billy Wilder, 1960), in the company of which it stands up well.

Saturday, April 29, 2017

Lost Highway (David Lynch, 1997)

|

| Patricia Arquette and Bill Pullman in Lost Highway |

Friday, April 28, 2017

Children of Nagasaki (Keisuke Kinoshita, 1983)

|

| Yukiyo Toake* and Go Kato* in Children of Nagasaki |

Maria Midori Nagai*: Yukiyo Toake

Grandmother: Chikage Iwashima

Makoto*: Masatomo Nakabayashi

Director: Keisuke Kinoshita

Screenplay: Keisuke Kinoshita, Taichi Yamada, Kazuo Yoshida

Based on writings by Takashi Nadai

Cinematography: Kozo Okazaki

Music: Chuji Kinoshita

I've seen only three films by Keisuke Kinoshita, but it's clear from those three that the director was haunted throughout his life by the tragedy that militarism inflicted on his country. Morning for the Osone Family (1946) is a depiction of what one family, divided by its attitudes toward the war, went through during its waning years. Twenty-Four Eyes (1954) is a sentimental yet oddly powerful anti-war film that takes place in a pastoral setting virtually untouched by bombing raids, yet deeply wounded by the conflict just over the horizon. Children of Nagasaki was one of his last films, and also one of his least known in the West -- it has no reviews on Rotten Tomatoes, a link to only one review on IMDb, and no entry at all in Wikipedia. But of the three it's the only one that directly confronts the physical horror of the war. It's essentially a biopic of Takashi Nagai, a physician who survived the nuclear explosion in Nagasaki and devoted himself to writing about the event and its aftermath, using his training as a radiologist to document the effects of radiation. Most of Nagai's writing was censored by the occupation authorities and not published until after his death in 1951 from leukemia, with which he had been diagnosed before the bomb fell on Nagasaki. In the film, Nagai is at work when the bomb is dropped, killing his wife. His two children are in the country with their grandmother, and with her help he goes about the task of rebuilding their home and their lives. The film, which begins with scenes from the visit to Nagasaki by Pope John Paul II in 1981, is suffused with Nagai's Roman Catholic faith, and while it's not clear if Kinoshita shared Nagai's faith -- the director is buried in a Buddhist cemetery -- he treats it with deep respect, even reverence. Children of Nagasaki is an uneven film, a little too heavily didactic, as the literally preachy use of the pope to open the film suggests. Three-quarters of the way in, Kinoshita suddenly and clumsily switches to a narrator, Nagai's grown son, reflecting on the life of his father. But he makes one striking choice: not to depict the horrors inflicted on the people of Nagasaki by the bomb at the point in the narrative when they occur, but instead to show them at the end of the film in a flashback, reinforcing the point that such a story can't really have a happy ending.

*These identifications are unconfirmed. IMDb lists only cast members and not the names of the roles they play. I've resorted to guesswork based on other sources in making the identifications. Corrections are welcome.

Thursday, April 27, 2017

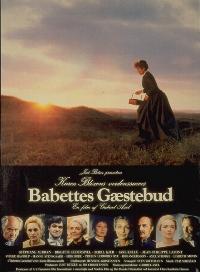

Babette's Feast (Gabriel Axel, 1987)

I had an odd experience this morning when I sat down to write this blog entry: I couldn't remember what film I watched last night. Ordinarily I'd ascribe this memory lapse to a "senior moment," but once I remembered that the film was Gabriel Axel's Babette's Feast, I thought I knew what caused it. This is what I call a "mood movie," one that, like some pieces of music, is designed -- or perhaps better, destined -- to put you into a certain emotional state. In the case of Babette's Feast, it's a kind of sweet melancholy, a state so ephemeral that almost anything can sweep it away -- as my experience of Babette's Feast was wiped away when I watched Survivor and Marvel's Agents of Shield, not exactly sweetly melancholic shows, immediately afterward on TV. This is not meant as a knock on Gabriel Axel's film, the screenplay for which he adapted from a story by Karin Blixen (aka Isak Dinesen). After all, it won the Oscar for best foreign language film, beating out among other contenders Louis Malle's Au Revoir les Enfants. It does what it does extraordinarily well, which is to tell a story, evoke a particular time and place, and present us with memorable characters. It centers on two sisters, Filippa (Bodil Kjer) and Martine (Birgitte Federspiel), who live in a small Danish village where they tend to the aging congregation of a small, austere sect which their father gathered together many years ago. A kindly man, he nevertheless dominated their lives to the extent that suitors were discouraged from marrying them. One of Filippa's suitors was an aging French operatic baritone, Achille Papin (Jean-Philippe Lafont), who was traveling through the village and happened to hear her singing in the church. Smitten with both her beauty and her voice, he offered to give her singing lessons, but when he proposed to take her to Paris and make her a diva, she took fright and turned him down. Some years later, during the unrest in Paris after the fall of the Second Empire in 1871, Papin sends to the sisters a young woman whose life has been threatened. Her name is Babette Hersant, his letter tells them, and she's an excellent cook who would be a fine housekeeper for them. Babette (Stéphane Audran) takes up residence with them and proves to be invaluable, bringing Parisian skills at seeking out the best food in the markets and bargaining for the best price. And then one day Babette receives word that an old lottery ticket has finally paid off to the tune of 10,000 francs. It is also the hundredth anniversary of the founding of the small congregation, and Babette proposes that she cook a dinner for the elderly, cranky, often fractious flock to celebrate. What the sisters don't know, but will soon learn, is that Babette had been one of the most celebrated chefs in Paris. The film climaxes in a triumphant union of the spiritual and the physical, as Babette's feast transforms the group into a true fellowship. Axel stages the feast beautifully, and cinematographer Henning Kristiansen emphasizes the transformation wrought by Babette's food with a steady focus on the faces of the congregants, which change from icy gray to rosy warmth as the meal progresses. There's a lovely little moment in which one of the sternest of the group reaches for a glass, discovers that it's filled with water, makes a face, and eagerly picks up a wine glass instead. As I've said, it's an ephemeral film, and I certainly don't think it deserved the Oscar over the more complex and powerful Au Revoir les Enfants, but on the other hand, what's so bad about feeling good?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)