A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Monday, May 22, 2017

Les Maudits (René Clément, 1947)

René Clément's Les Maudits has sometimes been known as The Damned, but lately people have turned to using the French title, perhaps to avoid confusion with Luchino Visconti's 1969 film called The Damned. The confusion is understandable: Both films are about Nazis. In Clément's film, a group of Nazi officials and their hangers-on board a submarine in April 1945. Seeing the writing on the wall, they hope to make it to South America to establish an outpost of what's left of the Reich, but as they're passing through the English channel they're spotted by a destroyer that drops depth charges. The sub is unharmed, but Hilde Garosi (Florence Marly) is knocked unconscious. She's the wife of one of the passengers, an Italian industrialist (Fosco Giachetti), and the mistress of another, a Nazi general (Kurt Kronenfeld), so a contingent is sent ashore into liberated France to find a doctor. Henri Vidal plays Dr. Guilbert, who also serves as a narrator for the film. Having been shanghaied into service on the sub, Guilbert knows that once his usefulness in treating Hilde, who has a mild concussion, is over his days are numbered, so he diagnoses a crew member with a sore throat as having diphtheria, necessitating quarantine and continued treatment. The rest is a fairly suspenseful and engaging submarine movie, with some superb camerawork in the confines of the ship. The cinematographer is Henri Alekan, who pulls off a great tracking shot down the length of the sub, which must have been quite a tour de force in the days before Steadicams. The screenplay by Clément, Jacques Rémy, and Henri Jeanson skillfully gives the mostly unsavory characters complexity, although Marly is a little too much the icily glamorous blond stereotype and Jo Dest, as the SS leader Forster, couldn't be more hissable. Michel Auclair has some good moments as Willy Morus, Forster's aide (and, by implication, boy toy). Although Vidal is the film's ostensible hero, top billing went to the great character actor Marcel Dalio (billed, as often he was in France, by only his surname) in what amounts to a small cameo role as Larga, the South American contact for the Nazis.

Sunday, May 21, 2017

Late Spring (Yasujiro Ozu, 1949)

|

| Hohi Aoki and Setsuko Hara in Late Spring |

Noriko Somiya: Setsuko Hara

Aya Kitagawa: Yumeji Tsukioka

Masa Taguchi: Haruko Sugimura

Katsuyoshi: Hohi Aoki

Shoichi Hattori: Jun Usami

Aiko Miwa: Kuniko Miyake

Jo Onodera: Masao Mishima

Kiku Onodera: Yoshiko Tsubouchi

Misako: Yoko Katsuragi

Shige: Toyo Takahashi

Seizo Hayashi: Jun Tanizaki

Director: Yasujiro Ozu

Screenplay: Kogo Noda, Yasujiro Ozu

Based on a novel by Kazuo Hirotsu

Cinematography: Yuharu Atsuta

Art direction: Tatsuo Hamada

Film editing: Yoshiyasu Hamamura

Music: Senji Ito

The opening of Yasujiro Ozu's Late Spring is deceptively calm: the usual establishing shots of landscape and buildings and trains, the kind of images with which Ozu typically punctuates his narratives, and a group of women gathering for a tea ceremony. One of the women is Noriko, whose brilliant smile is also deceptive. This is the first film in Ozu's so-called "Noriko trilogy," to be followed by Early Summer (1951) and Tokyo Story (1953), in each of which Setsuko Hara plays a woman named Noriko. The three Norikos have nothing in common except that they are all unmarried. (In Tokyo Story she is a widow.) The Noriko of Late Spring lives with her father, Shukichi, who is played by Ozu regular Chishu Ryu. (In Early Summer, Ryu plays Hara's brother, and in Tokyo Story her father-in-law.) The deceptions of what might be called the "get-acquainted" section of Ozu's film, which establishes for us the relationships among the characters, lie in the apparent happiness and contentment of father and daughter and the untroubled world in which they live. But Late Spring was filmed only four years after the end of the war that devastated Japan, which was still under occupation by American forces. The wounds and pain of the country and its people are invisible in the film, partly because of occupation censorship, but they provide a kind of tension in the viewer who knows what the characters must have suffered. There is only a brief mention of this in Late Spring: Noriko has been to the doctor and reports that her health has improved. Another character's reference to "forced work during the war" sheds some light on what may have caused her illness. Later, Noriko and her father visit Kyoto, and he remarks how much nicer it is than "dusty" Tokyo, obliquely referencing wartime destruction. The central deception, however, lies in Noriko's apparent contentment with her unmarried state: She feels it is her duty to spend her life caring for her widowed father, and brushes off any suggestions that at 27 she should really be thinking about getting married -- or worse, that her father might choose to remarry. She calls the second marriage of one of her father's friends "filthy." We who have seen this situation before, however, realize that the deception Noriko is perpetrating is on herself. Perhaps because she has lived through so much change and upheaval, Noriko is trying to persuade herself that her current happiness serving her father can be made permanent. And so she suffers a shock when her father displays interest in a beautiful widow, and another when he suggests that she might meet the young man her Aunt Masa thinks would be a suitable husband for Noriko. What Ozu and his frequent collaborator Kogo Noda establish here, working from a novel called Father and Daughter by Kazuo Hirotsu, is worthy of Henry James or Jane Austen -- I think particularly of Austen's Emma Woodhouse and her self-deluding attachment to her father. Eventually, Noriko is persuaded into marriage -- in a masterstroke of direction we never even see the groom -- by her father's lie: He claims that he has been planning to remarry, thereby eliminating any objection Noriko could have to seeking her own path to fulfillment. The film ends with a melancholy image of Shukichi alone, peeling an apple -- a kind of Jamesian twist on an Austenian situation. This magisterial example of Ozu's late style -- low camera angles, absence of pans and dissolves, emphasis on the somewhat claustrophobic interiors of the Japanese home -- is reinforced by Tatsuo Hamada's art direction and Yuharu Atsuta's cinematography, but most of all by the superb performances of Hara and Ryu.

Friday, May 19, 2017

Angel Face (Otto Preminger, 1953)

|

| Robert Mitchum and Jean Simmons in Angel Face |

Diane Tremayne: Jean Simmons

Mary Wilton: Mona Freeman

Charles Tremayne: Herbert Marshall

Fred Barrett: Leon Ames

Catherine Tremayne: Barbara O'Neil

Director: Otto Preminger

Screenplay: Frank S. Nugent, Oscar Millard

Based on a story by Chester Erskine

Cinematography: Harry Stradling Sr.

Music: Dimitri Tiomkin

Otto Preminger was about to take on the Production Code when he made Angel Face: His next film was The Moon Is Blue (1953), a rather tepid little romantic comedy that offended the Code enforcers because its heroine, though relentlessly virginal, demonstrated an awareness of and interest in extramarital sex that was one of the Code's taboos. With the backing of United Artists, Preminger went ahead and made the film, releasing it without the Code's imprimatur. The result was a succès de scandale, a hit far beyond any actual merits of the film, after it was condemned by the Catholic Legion of Decency and by some local censorship boards. Two years later, Preminger and United Artists would follow the same procedure with The Man With the Golden Arm (1952), a film about drug addiction that also flouted some of the Code's prohibitions. Preminger's stand is usually cited among the landmarks leading to the end of film industry censorship. I mention all this because I was struck by how Preminger also ignores the Code's conventional morality in Angel Face, which makes it clear that Frank Jessup has been sleeping with his girlfriend, Mary Wilton -- among other things, he reveals that he knows what she wears to bed, and when he goes to see her, she's in her slip getting ready to go out and doesn't bother coyly pulling on the usual bathrobe. The thing is, Mary is the film's "nice girl," the character meant to be the foil to the film's murderous Diane Tremayne. But Diane doesn't smoke or drink, and Mary does. Some of the reason for Preminger's blurring of the lines between the usual Hollywood ideas of good and bad in these characters probably stems from a desire to build suspense, keeping us from being entirely sure that Diane is the one who turned on the gas in her stepmother's room or if she really is guilty of the murder for which she stands trial. But I suspect that it has more to do with Preminger's desire to pull his characters out of the usual pigeonholes of Hollywood melodrama, to make them plausible, enigmatic human beings. To some extent he's fighting the script, adapted by Frank S. Nugent and Oscar Millard (with some uncredited help by Ben Hecht) from a story by Chester Erskine, which on the face of it is the usual stuff about a conniving woman who loves her daddy too much and who stands to gain from her stepmother's death, ensnaring an unsuspecting man along the way. Mitchum's sleepy-eyed raffishness could have been used to make him the usual tough-guy collaborator of a femme fatale, like Fred MacMurray's Walter Neff in Double Indemnity (Billy Wilder, 1944) or John Garfield's Frank Chambers in The Postman Always Rings Twice (Tay Garnett, 1946), but it's not a knock on those two great noirs to say that Preminger does something more subtle with Mitchum's Frank Jessup: He's an accomplice and a victim only by accident, letting his hormones put him in harm's (i.e., Mary's) way, and struggling ineffectually, even a little tragically, not to be dragged down by her. Angel Face is not as well-known as those other films, but with its solid performances, its effective and unobtrusive score by Dimitri Tiomkin, and its knockout of an ending, it deserves to be.

Thursday, May 18, 2017

Innocence Unprotected (Dusan Makavejev, 1968)

|

| Ana Milosavljevic in Innocence Unprotected |

Wednesday, May 17, 2017

Scarlet Street (Fritz Lang, 1945)

Fritz Lang's Scarlet Street is based on the same novel by Georges de la Fouchardière that Jean Renoir had adapted for his 1931 film that retained the novel's title, La Chienne. Both films came at oddly significant points in their directors' careers: Renoir's was only his second talkie, but one in which he demonstrated his mastery of the relatively new medium by a creative use of ambient sound. Lang's was made just as World War II was ending -- a moment when it became possible for him to return to Europe, which he had fled to avoid Nazi persecution. Lang chose, however, to stay on in Hollywood for 12 more years, though he grew increasingly annoyed at the creative restrictions imposed on him by the big studios and Production Code censorship. In this context, Scarlet Street stands out as edgy and somewhat defiant. The Code prescribed a kind of lex talionis: any criminal act demands a punishment equivalent in kind and degree. But in Scarlet Street, Christopher Cross (Edward G. Robinson) gets away with not only fraud and theft but also murder -- a double murder, if you consider that the man wrongly accused of the murder goes to the electric chair for it. Cross is punished by homelessness and by auditory delusions of the voices of those who drove him to crime, but that's much less severe than the Code usually prescribed. There were those, of course, including censors in New York State, Milwaukee, and Atlanta, who noticed the Code's laxness and proceeded to ban the film on their own. Today, Scarlet Street is regarded as a classic, one of the premier examples of film noir at its darkest. It doesn't quite measure up to Renoir's version, perhaps because Renoir was freer in expressing his vision of the material than Lang was. Renoir's film had touches of humor and a gentler, more ironic ending, but the ending of Scarlet Street is entirely in keeping with the tone of the rest of the film, with its traces of unfettered Lang: for example, the shocking viciousness of Johnny Prince (Dan Duryea), who if you know how to decode the Code is clearly the pimp to the prostitute Kitty March (Joan Bennett). And Cross's behavior at the end of the film, derelict and delusional, echoes some of the frantic paranoia of Peter Lorre's child murderer in Lang's M (1931). The screenplay is by Dudley Nichols.

Tuesday, May 16, 2017

Je Tu Il Elle (Chantal Akerman, 1974)

|

| Chantal Akerman in Je Tu Il Elle |

Monday, May 15, 2017

The Woman on the Beach (Jean Renoir, 1947)

Imagine The Woman on the Beach if Jean Renoir had made it in France with, say, Simone Signoret, Gérard Philipe, and Jean Gabin, and perhaps you can see what I mean when I say it's the best example of the kind of pressures Renoir felt during his war-imposed exile in Hollywood. Although the war was over, Renoir was under contract to RKO for two more pictures, but after the failure of The Woman on the Beach, the studio canceled the contract, so it was his last American film. If he had made the film in France, he wouldn't have been subjected to the heavy-handedness of Production Code censorship, which almost killed the film from the outset when the Code administrator, Joseph I. Breen,* declared the story, adapted from a novel by Mitchell Wilson, "unacceptable ... in that it is a story of adultery without any compensating moral values." Somehow Breen was persuaded to give in. But Renoir also had to put up with the studio star system, which required performers to look glamorous and handsome even in the most adverse situations. Even though Joan Bennett's character, Peggy Butler, spends a lot of time on the beach doing things like gathering firewood, her hair and makeup are always perfect. After an unfavorable preview of the film, the studio forced reshoots and made some drastic cuts -- the existing version is only 71 minutes long -- that displeased Renoir. What we have now is a sometimes fascinating, sometimes incoherent film. There's an on-again, off-again relationship between a Coast Guard officer, Scott Burnett, played by Robert Ryan, and a young woman named Eve, played by the starlet Nan Leslie, that serves no essential function in the story. Scott's nightmares about being on a sinking ship during wartime and an encounter on the beach with a ghostly woman who looks something like Eve loom large in the early part of the film but then mysteriously vanish along with any other symptoms of the PTSD Scott supposedly suffers from. The focus of the story is on Scott's affair with Peggy -- they apparently have sex in a shipwreck that has washed up on the beach -- and his suspicions about Peggy's husband, Tod (Charles Bickford), a famous painter who is now blind, the result of a fight in which Peggy threw something that severed his optic nerve. But Scott thinks Tod is faking his blindness and puts him to the test, which Tod passes by falling off a cliff without doing himself serious harm. There's a good deal of overheated dialogue: "Peg, you're so beautiful ... so beautiful outside, so rotten inside." In the end, there's a conclusion in which nothing is concluded: Scott seemingly tries but fails to drown both himself and Tod; Tod sets fire to the cabin that contains his cherished surviving paintings; he and Peggy set off for New York; and Scott retires from his commission in the Coast Guard. Some of this might have made emotional sense in a better-crafted film, one not subject to the tinkering and scrubbing that the studio and the censors enforced. Still, Bennett, Ryan, and Bickford perform with conviction, and there are those who find even the film's chaotic presentation of erotic entanglements compelling.

*Renoir doesn't seem to have nursed any hard feelings against Breen: He cast his son, Thomas E. Breen, in a key role in The River (1951).

*Renoir doesn't seem to have nursed any hard feelings against Breen: He cast his son, Thomas E. Breen, in a key role in The River (1951).

Sunday, May 14, 2017

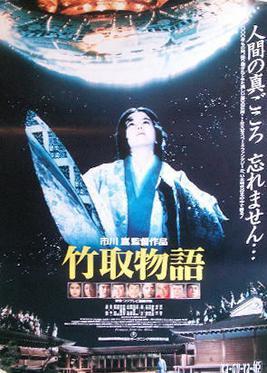

Princess From the Moon (Kon Ichikawa, 1987)

In eighth-century Japan, a man (Toshiro Mifune) and his wife (Ayako Wakao) are mourning the death of their 5-year-old daughter, Kaya. They live beside a forest of bamboo, whose stalks the man cuts and turns into baskets and other artifacts, which he sells to make a living. One night they see a bright light and their hut is shaken by a huge tremor. The next morning, when the man goes out to investigate he finds near his daughter's grave a large egg-shaped object. It begins to crack open and as he watches, a baby crawls from it and begins to grow rapidly until it assumes the form of his dead child. The man and his wife raise the girl as their daughter, Kaya, and discover that the egg-shaped object from which she emerged is pure gold, so they become rich enough to move into a large house. Kaya swiftly grows into a young woman (Yasuko Sawaguchi) whose beauty attracts high-born suitors. But she has brought with her a small crystal ball that eventually reveals her secret: She is from the moon, the sole survivor when the ship that was carrying her crashed. To ward off her suitors, she proposes impossible tasks to win her hand. And then the ball reveals that at the next full moon, a ship will arrive to carry her home. The entire realm has fallen in love with Kaya, and on the night of the full moon, troops are stationed about the house to shoot down any arriving ships. Up to this point, Kon Ichikawa's Princess From the Moon has been a charmingly magical fantasy film, a smart adaptation of an ancient Japanese folktale, The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter, with beautiful sets by Shinobu Muraki, costumes by Emi Wada, and color cinematography by Setsuo Kobayashi. But suddenly Ichikawa imposes on the setting a spaceship out of Close Encounters of the Third Kind (Steven Spielberg, 1977), and Kaya is drawn up into it in flowing robes and accompanied by what appear to be glowing cherubs, an image that recalls Renaissance paintings of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary, like this one by Rubens:

It's a startling shift in tone and technique, to say the least, especially when compounded by the insertion of a pop song, "Stay With Me," by Peter Cetera behind the end credits. Critics, too, were jarred by the overlaying of a sci-fi trope on a traditional tale, but audiences seemed to like it. A somewhat more traditional version of the story, The Tale of the Princess Kagya (Isao Takahata), was produced by Studio Ghibli in 2013 and was nominated for the animated feature Oscar.

It's a startling shift in tone and technique, to say the least, especially when compounded by the insertion of a pop song, "Stay With Me," by Peter Cetera behind the end credits. Critics, too, were jarred by the overlaying of a sci-fi trope on a traditional tale, but audiences seemed to like it. A somewhat more traditional version of the story, The Tale of the Princess Kagya (Isao Takahata), was produced by Studio Ghibli in 2013 and was nominated for the animated feature Oscar.

Saturday, May 13, 2017

Night and the City (Jules Dassin, 1950)

It's fun sometimes to go back and read the reviews Bosley Crowther wrote for the New York Times, panning films that are now regarded as classics. Crowther, if you've forgotten, was the lead film critic for the Times for 27 years, until he panned Bonnie and Clyde (Arthur Penn, 1967) and persisted in attacking the film in follow-up articles until the Times nudged him into retirement. My generation grew up thinking of Crowther as the classic fuddy-duddy. Some of the harsh moralizing that marked his Bonnie and Clyde diatribe was present throughout his career, as in, for example, his comments in his review of Jules Dassin's Night and the City, which he called "a pointless, trashy yarn," a "a turgid pictorial grotesque," "a melange of maggoty episodes," and a "cruel, repulsive picture of human brutishness." It almost makes you want to run right out and see it, doesn't it? But there's a part of me that thinks the old foof was onto something: Night and the City is just a little too dark to be credible, and some elements of it -- such as Richard Widmark's over-the-top performance and the expressionistic camera angles of cinematographer Mutz Greenbaum (billed as Max Greene) -- verge on film noir self-parody. Still, there's a great energy in Night and the City, which often reminds me of Dickens's forays into the underworld -- the titular city is London -- especially when it comes to character names. The chief villain (Francis L. Sullivan, imitating Sydney Greenstreet) is a Mr. Nosseross -- his given name is Philip, not Rye -- and there's a minor character with the über-Dickensian name of Fergus Chilk. Widmark plays Harry Fabian, whose life is a continuous hustle, trying to gather enough money to finance his various get-rich-quick schemes. His long-suffering girlfriend, Mary Bristol (Gene Tierney, in a smaller role than her billing suggests), is a singer in a clip joint run by the Nosserosses -- Philip and his wife, Helen (Googie Withers). Eventually, Harry overreaches by trying to loosen the hold on the pro wrestling exhibition racket in London held by Kristo (Herbert Lom), whose star wrestler is known as the Strangler (Mike Mazurki). Harry cons an honest old Greek wrestler named Gregorius (Stanislaus Zbyszko) into staging a bout between Gregorius's protégé, Nikolas of Athens (Ken Richmond) and the Strangler, but everything goes to hell when Nosseross withdraws his promised financial support. There is a great wrestling scene in which Gregorius himself takes on the Strangler, who has broken Nikolas's wrist. Gregorius wins, but dies of a heart attack afterward, one of the many deaths the movie accumulates. The film makes great atmospheric use of its London setting, which was necessitated because Dassin was about to be blacklisted in Hollywood -- it's to the credit of 20th Century Fox head Darryl F. Zanuck that he warned Dassin of this and, when Dassin decided he would seek work in Europe, allowed him to make the film in London.

Friday, May 12, 2017

Manchester by the Sea (Kenneth Lonergan, 2016)

Sometimes, to appreciate how good a film is you have to imagine how bad it could have been. The conventional way of telling a story is beginning-middle-end, cause-effect-remedy, disease-diagnosis-cure. But if Kenneth Lonergan had taken that strict linear approach in crafting Manchester by the Sea, we would have been deprived of the element of discovery that makes it such a powerful film. To put it this way, Lonergan could have opened with the calamitous event that so blights the life of Lee Chandler (Casey Affleck), and then shown the breakup with his wife, Randi (Michelle Williams); his efforts to lose himself in menial work as a handyman/custodian in Boston; the death of his brother, Joe (Kyle Chandler), and Lee's return to Manchester; the discovery that Joe has made him guardian of Joe's son, Patrick (Lucas Hedges), and the subsequent attempts to arrange his life around that fact. But by postponing the revelation of the terrible event in Lee's life, placing it in a flashback, Lonergan makes it what it has to be: the very center of the film. We want to know what is troubling Lee, why he's so blocked emotionally, and Lonergan makes us wait for the answer, to speculate what it might be. When the revelation comes that he accidentally killed his small children, it probably fulfills what many of us had guessed it might be, so it doesn't come as a brutal surprise but as an elucidation. To put it at the start of the film, including Lee's aborted attempt at suicide, would have turned the film into a sentimental slog toward redemption. But by first showing us the ways in which Lee has responded by hiding away or lashing out at comforters or the curious -- by putting the middle before the beginning, the effect before the cause -- Lonergan focuses on Lee's continuing everyday pain, not on the enormity of what caused it. And then there's the ending: poignant, inconclusive, but at least somewhat hopeful. A conventional ending that provided balm for the pain, a cure for the disease, would have been phony. We may want the film to end with Lee finding some consolation like that of new fatherhood with Patrick, a rapprochement with Randi, even some kind of successful therapy or -- like Elise (Gretchen Mol), Joe's druggie ex-wife and Patrick's strayed mother -- submission into religious faith, but we would be satisfying our desire for a tidy narrative, not Lee's deep needs. Lonergan handles the traditional religious "cure" brilliantly, showing Patrick's discomfort at the evangelical piety of Elise and her new husband, Jeffrey (Matthew Broderick), and his complaint to Lee that Jeffrey is "Christian." Lee reminds him that they're Christians too -- "Catholics are Christians" -- ironically widening the gulf between Patrick and his mother and her husband. Lee's Catholicism is steeped in guilt, an emotion he knows too well and cannot imagine a life without. The strength of a film like Manchester by the Sea lies in its acknowledgment that life is too shaggy, bristly, and spiky to be neatly wrapped up with cures and fixes for whatever ails it.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

_poster.jpg)