A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Wednesday, November 30, 2016

Tuesday, November 29, 2016

Nothing Sacred (William A. Wellman, 1937)

It's a bit startling to see a classic screwball comedy like Nothing Sacred in color. We're used to movies from the 1930s in the crisp elegance of black and white, so if you came across this movie without knowing anything about it, you might think it was one of those films that Ted Turner tried to "colorize." Part of the problem is that the tones in early Technicolor films are so muted: Some have faded with age, but getting the true sharp color contrasts that we're used to was more difficult in these early films, especially since Technicolor had very conservative ideas about what could be done with the process, and its "consultants," like the oft-credited Natalie Kalmus, the wife of the company's founder, were there to peer over the cinematographer's shoulder at all times. In addition, one of the problems with the color on Nothing Sacred is that a lapse of copyright on the film allowed many inferior prints to circulate before it could be restored to its original version. To my way of thinking, color adds little to this particular film, except in the glimpses of New York City in 1937. Carole Lombard plays Hazel Flagg, who, through a misdiagnosis by her small-town Vermont physician, Dr. Downer (Charles Winninger), is thought to be dying of radium poisoning. A New York reporter, Wally Cook, reads a short item about Hazel in the newspaper and persuades his editor, Oliver Stone (Walter Connolly), that it has the makings of a circulation-building sob story. Although Hazel and her doctor have subsequently learned that she's perfectly healthy, they agree to go along with the scheme to celebrate her as a dying heroine in the big city. And so it goes, in a frequently deft skewering of high-pressure journalism -- the very thing you might expect from the screenwriter, Ben Hecht, a former newspaperman who did a similar skewering in his play The Front Page. After Hecht had a falling-out with the film's producer, David O. Selznick, the screenplay was worked over by a number of uncredited wits, including Dorothy Parker, Moss Hart, George S. Kaufman, and Budd Schulberg. The film could have used a somewhat lighter hand at directing: William A. Wellman is best known as a tough guy -- his nickname was "Wild Bill" -- with credits like Wings (1927), The Public Enemy (1931), The Story of G.I. Joe (1945), and Battleground (1949), but he does get to stage a very funny fight scene between Lombard and March.

Monday, November 28, 2016

The Sea of Trees (Gus Van Sant, 2015)

For a movie that attempts a "feel-good" ending, The Sea of Trees sure does spend a lot of time making you feel bad, from the moment its grim-faced protagonist, Arthur Brennan (Matthew McConaughey), arrives in Japan. He plans to kill himself in the "Suicide Forest" near Mount Fuji. But then he tries to help Takumi Nakamura (Ken Watanabe), a man he meets there, find his way out of the forest, and encounters all manner of hardships and injuries. There are also flashbacks to Arthur's troubled marriage and the death of his wife, Joan (Naomi Watts). We are plunged into one misery after another before a twist into fantasy convinces Arthur not only that life is worth living but also that love persists after death. Yet the misery dominates the tone of the film, despite three excellent actors and a well-regarded director, Gus Van Sant. Some of the blame must fall on the screenwriter, Chris Sparling, but mostly it seems to be a failure to leaven the material with anything that gives us a sense that the promise of its ending has been earned. Imagine Ghost (Jerry Zucker, 1990) without Whoopi Goldberg and instead two hours of moping around by Demi Moore recalling life with Patrick Swayze, and you'll have a sense of the overall effect of The Sea of Trees. One major problem, I think, is in the miscasting of McConaughey as the lead. He's a very good film actor, as his Oscar-winning performance in Dallas Buyers Club (Jean-Marc Vallée, 2013), his scene-stealing bit in The Wolf of Wall Street (Martin Scorsese, 2013), and his work on the first season of the series True Detective (2014) amply demonstrates. But he is, I think, a character lead, terrific in roles full of wit and sass and energy, whereas what's called for in films like The Sea of Trees is a conventional romantic leading man. As hard as he works to make it plausible, his character in this film never rings true. But then not much else in the film does, either.

Sunday, November 27, 2016

The Cameraman (Edward Sedgwick and Buster Keaton, 1928)

|

| Buster Keaton in The Cameraman |

Sally: Marceline Day

Stagg: Harold Goodwin

Editor: Sidney Bracey

Cop: Harry Gribbon

Director: Edward Sedgwick, Buster Keaton

Screenplay: Clyde Bruckman, Lew Lipton, Richard Schayer; titles by Joseph Farnham

Cinematography: Reggie Lanning, Elgin Lessley

Art direction: Fred Gabourie

Film editing: Hugh Wynn, Basil Wrangell

The Cameraman, Buster Keaton's first film under contract to MGM, isn't quite up to the standards set by The General (Keaton and Clyde Bruckman, 1926) or Steamboat Bill Jr. (Charles Reisner and Keaton, 1928), but then what is? Keaton plays a sidewalk photographer who is smitten with Sally, a receptionist in the studios of MGM's newsreel department. To try to win her, he buys an antique movie camera and sets out to get a job with the studio. Of course he screws up his first attempt and is shown the door, but several adventures later he succeeds in getting not only the job but also the girl. Keaton would come to regret signing with MGM, a studio strongly producer-driven, and he fought with producer Lawrence Weingarten over the concept and script for The Cameraman, eventually getting his own way after persuading the studio's creative director, Irving G. Thalberg, to back him. But the relationship with the studio was fated to end, especially when sound arrived and Keaton came to be seen as a relic of a fading era. There are some masterly moments in The Cameraman, such as the scene in which he and a much larger man struggle to change into their swimsuits in a too-small changing cubicle, (The scene, incidentally, gives us a glimpse of a shirtless Keaton, revealing a strikingly toned athletic body, the product of years of doing his own stunts.) There are perhaps too many scenes that Keaton is forced to share with a very cute trained monkey, distracting us from his own work, but this is probably the last of the great Keaton films.

Saturday, November 26, 2016

Stalker (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1979)

|

| Aleksandr Kaidanovsky in Stalker |

Andrei Tarkovsky's dystopian fantasy has something of the flavor of a Russian folk tale. The archetypes are there: the perilous quest, the trio of seekers, the anagnorisis, the catharsis, the disillusioned return. The title character, splendidly played by Aleksandr Kaidanovsky, is not a "stalker" in the current sexual sense but rather a man who guides others into the Zone, a mysterious area cordoned off from the rest of the world by the military. In the Zone, the Stalker says, is a Room that fulfills each person's secret desires. The men he guides in the film are a cynical Writer (Anatoliy Solonitsyn) and an ambitious Professor (Nikolay Grinko) -- archetypes of art and science, who throughout their journey make the cases for their respective world-views. The film begins in monochrome -- sometimes stark black-and-white, sometimes a bilious orange -- in the Stalker's bedroom, where he shares a bed with his wife (Alisa Freindlich) and his young daughter, whom they call Monkey (Natasha Abramova). Before he leaves to meet the the Writer and Professor, the wife chides him for taking on another dangerous mission. To get to the Zone, they have to pass through a heavily guarded section, and when they reach it, the film turns to color. But the Zone is no Oz, despite the obvious allusion. It is distinguished from the bleak industrial outside world by an abundance of vegetation that covers not only ruins of a former industrial society but also the tanks, weaponry, and corpses of the military that tried to invade and conquer it. The Zone is also magical, continually frustrating attempts to move through it and reach the Room, but the Stalker has learned how to anticipate and avoid its tricks. He says that as a Stalker he is forbidden to enter the Room, but the truth is that he knows the fate of an earlier Stalker, called Porcupine, who did enter it. Tarkovsky's usual long takes demand actors of considerable skill, and all of the company possess it. Although Freindlich's role as the wife is a smaller one, since she doesn't accompany them on the journey, she has a compelling scene at the film's end that's a master class in how to deliver a monologue. The shoot was a legendarily troubled one, since the locations were actual badly polluted industrial ruins, and many of the crew grew ill from the toxins in the abandoned chemical plant -- there are those who claim that the deaths from lung cancer of Tarkovsky, his wife, Larisa, who was a second-unit director, and Solonitsyn were a result of exposure to chemicals during the filming of Stalker. In fact, much of the film was shot at least twice, after cinematographer Georgi Rerberg was fired and replaced with Aleksandr Knyazhinsky, doubling the exposure of many of the cast and crew. Backstory aside, Stalker is a fascinating glimpse into Tarkovsky's mind and milieu.

Friday, November 25, 2016

Eastern Promises (David Cronenberg, 2007)

The Russian mafia seems to have supplanted the Italian kind in the popular imagining of the violent criminal world. It has long been a staple of TV crime shows like Law & Order, but David Cronenberg gave it the most impressive and terrifying embodiment yet in Eastern Promises. The film, set in London, is a strikingly globalized production, with a Canadian director and English screenwriter (Steven Knight) and actors who are Danish-American (Viggo Mortensen), British (Naomi Watts), German (Armin Mueller-Stahl), French (Vincent Cassel), Polish (Jerzy Skolimowski), and Irish (Sinéad Cusack). Yet the film somehow maintains a strong semblance of authenticity, thanks to strong performances. Mortensen, long a favorite of mine, gives an intensely compelling, and Oscar-nominated, portrayal of a Russian undercover agent infiltrating the mob. His celebrated battle in the steam bath, in which he, naked and unarmed, is attacked by two well-clothed thugs carrying linoleum knives should never let you take another two-against-one battle in a James Bond film seriously. (Or not until Daniel Craig does it in the nude.) Mueller-Stahl demonstrates once again that one can smile and smile and be a villain, and Cassel steals scenes with his portrayal of Mueller-Stahl's careless, dissipated weakling of a son. My only complaint about Eastern Promises is a rather saccharine ending to Watts's portion of the story. The story of Mortensen's character ends inconclusively, with his apparent ascension to the role of boss of the mob, a risky position for an undercover agent. A sequel has been proposed and postponed, and at last report seems to be dead.

Thursday, November 24, 2016

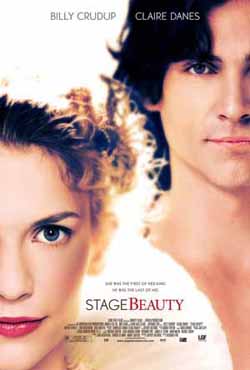

Stage Beauty (Richard Eyre, 2004)

It's a measure of how the discourse on sexual identity has changed over the past 12 years that Stage Beauty, in which it is a central theme, seems now to have missed the mark completely. Billy Crudup, an actor who should be a bigger star than he is, plays Edward Kynaston, an actor in Restoration London who was noted for his work in female roles at a time when such parts were usually still played by boys and men. Kynaston, as the film tells us, was praised by the diarist Samuel Pepys as "the loveliest lady that ever I saw in my life." As the film begins, he is performing as Desdemona in a production of Othello, and is aided by a dresser, Maria (Claire Danes), who longs to act. After his performance ends, she borrows his wig, clothes, and props, and performs in a local tavern as "Margaret Hughes." When King Charles II (Rupert Everett) lifts the ban on women appearing on stage, Kynaston not only finds his career threatened, but when the king's mistress, Nell Gwynn (Zoë Tapper), overhears him fulminating about the inadequacy of actresses, she persuades the king to forbid men from playing women's roles: The king gives as his reason that it encourages "sodomy." Although the actual Kynaston performed male as well as female roles, in the film he is stymied by an inability to act male parts. Eventually, Maria, who is having trouble with her own new career, calls upon Kynaston to coach her in his most famous role, Desdemona, while at the same time teaching him how to act like a man on stage. Together, they appear as Othello and Desdemona and, with a violently naturalistic performance of the death scene, bring down the house. The premise, taken from a play by Jeffrey Hatcher, who also wrote the screenplay, allows for some insight into the nature of gender, but the film never approaches it satisfactorily. Instead, we have a conventional ending that suggests not only that Kynaston and Hughes revolutionized acting with less stylized performance -- something that certainly didn't occur in the classically oriented Restoration theater -- but also that they fell in love. Earlier in the film, Kynaston is shown in a same-sex relationship with George Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham (Ben Chaplin), who leaves him to get married. The film never quite resolves whether Kynaston is gay, bi, sexually fluid, or simply somehow confused by having been celebrated as a beautiful woman. And while it's risky to apply 21st-century psychology to 17th-century sexual mores, Stage Beauty's indifference to historical accuracy seems to demand that it do so. As unsatisfactory a film as it is, Stage Beauty has a few things to recommend it, starting with Crudup's fine performance. Danes is hindered by a screenplay that never concentrates on her character long enough to bring it into focus, but she and Crudup have strong chemistry together. And the supporting cast includes such British acting stalwarts as Everett, Chaplin, Tom Wilkinson, Richard Griffiths, and Edward Fox, as well as Hugh Bonneville, now best known for Downton Abbey, as Pepys. It's startling to see Robert Crawley, Earl of Grantham, peering out from beneath a Restoration periwig.

Wednesday, November 23, 2016

What's Up, Doc? (Peter Bogdanovich, 1972)

As a film genre, the screwball comedy flourished for about a decade, from 1934 to 1944, or from Twentieth Century (Howard Hawks, 1934) to Hail the Conquering Hero (Preston Sturges, 1944.) Like so much else in movie history, including the Western, it was killed off by television, by half-hour sitcoms like I Love Lucy that slurped up its essence and made the 90-minute theatrical versions seem like overkill. We can still glimpse some of the heart of the screwball comedy in films like David O. Russell's Silver Linings Playbook (2012) and American Hustle (2013) or Wes Anderson's The Royal Tenenbaums (2001), but Peter Bodganovich's What's Up, Doc? is probably the last pure example of the genre as it was in its heyday. Like the masters of the genre -- Hawks and Sturges are the masters, but Gregory La Cava, George Stevens, Mitchell Leisen, and Frank Capra made worthy contributions -- Bogdanovich followed a few rules: One, get stars who usually played it straight to make fools of themselves. Two, make use of as many comic character actors as you can stuff into the film. Three, never pretend that the world the film is taking place in is the "real world." Four, never, ever let the pace slacken -- if your characters have to kiss or confess, make it snappy. On the first point, Bogdanovich found the closest equivalents to Cary Grant and Katharine Hepburn (or Clark Gable, Joel McCrea, James Stewart on the one hand, Rosalind Russell, Claudette Colbert, Jean Arthur on the other) that he could among the stars of his day. Ryan O'Neal was coming off the huge success of the weepy Love Story (Arthur Hiller, 1970) and a five-year run on TV's Peyton Place and Barbra Streisand had won an Oscar for Funny Girl (William Wyler, 1968). Granted, O'Neal is no Cary Grant: His timing is a little off and he overdoes a single exasperated look, but he makes a suitable patsy. But has Streisand ever been more likable in the movies? She plays the dizzy troublemaker with relish, capturing the essence of Bugs Bunny -- the other inspiration for the movie -- to the point that you almost expect her to turn to the camera and say, "Ain't I a stinker?" As to the second point, we no longer have character actors of the caliber of Eugene Pallette, Franklin Pangborn, or William Demarest, but Bogdanovich recruited some of the best of his day: Kenneth Mars, Austin Pendleton, Michael Murphy, and others, and introduced moviegoers to the sublime Madeline Kahn. And he set it all in the ever-picturesque San Francisco, while making sure no one would ever confuse the movie version with the real thing, including a chase sequence up and down its hills that follows no possible real-world path. And he kept the pace up with gags involving bit players: the pizza maker so distracted by Streisand that he spins his dough up to the ceiling, the banner-hanger and the guys moving a sheet of glass, the waiter who enters a room with a tray of drinks but takes one look at the chaos there and turns right around, the guy laying a cement sidewalk that's run over so many times by the car chase that he flings down his trowel and jumps up and down on his mutilated handiwork. This is masterly comic direction of a sort we don't often see -- and, sadly, never saw again from Bogdanovich, whose career collapsed disastrously with a string of flops in the mid-1970s. Here, he was working with a terrific team of writers, Buck Henry, David Newman, and Robert Benton, who turned his story into comedy gold.

Tuesday, November 22, 2016

The Passion of Joan of Arc (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1928)

|

| Renée Jeanne Falconetti in The Passion of Joan of Arc |

*So far, Filmstruck hasn't moved much beyond streaming on the computer, though it's supposed to be included on Roku early next year. In my household, with two others competing for bandwidth, this meant that I had frequent interruptions as the film refreshed itself. Oddly enough, I didn't mind as much as I usually would, because Dreyer's images are so compelling that I was content to pause and study them.

Monday, November 21, 2016

Wizard of Oz (Larry Semon, 1925)

|

| Dorothy Dwan and Larry Semon in Wizard of Oz |

Sunday, November 20, 2016

Queen Margot (Patrice Chéreau, 1994)

|

| Daniel Auteuil and Isabelle Adjani in Queen Margot |

Saturday, November 19, 2016

Jamaica Inn (Alfred Hitchcock, 1939)

According to Stephen Whitty's excellent The Alfred Hitchcock Encyclopedia, the director thought Jamaica Inn "completely absurd" and didn't even bother to make his familiar cameo appearance in it. Hitchcock was right: It's a ridiculously plotted and often amateurishly staged film -- although Hitchcock must take some of the blame for the scenes in which characters sneak around talking in stage whispers and pretending they're hidden from their pursuers when they're in plain sight for anyone with average peripheral vision. Much of Hitchcock's attitude toward the film has been ascribed to his clashes with Charles Laughton, who was an uncredited co-producer and resisted any attempts by the director to rein in one of his more ridiculous performances. As Sir Humphrey Pengallan, the county squire and justice of the peace who is secretly raking in a fortune by collaborating with smugglers who loot shipwrecked vessels after murdering their crew, Laughton wears a fake nose and oddly placed eyebrows and hams it up mercilessly. Maureen O'Hara, in her first major film role, struggles with a confusingly written character who sometimes displays fire and initiative and at other times seems alarmingly obtuse. The rest of the cast includes such stalwarts of the British film and stage as Leslie Banks, Emlyn Williams, and Basil Radford, with a surprising performance by Robert Newton as the movie's romantic lead, Jem Traherne, an agent working undercover to expose the smugglers. You look in vain at the young Newton for traces of his terrifying Bill Sykes in Oliver Twist (David Lean, 1948) or his Long John Silver in Treasure Island (Byron Haskin, 1950). The production design is handsome, and the film begins with an exciting storm at sea, but the screenplay, based on a Daphne Du Maurier novel and written by the usually capable Sidney Gilliat and Joan Harrison, quickly falls apart. Hitchcock's last film in England, Jamaica Inn was a critical flop but a commercial success.

Friday, November 18, 2016

The Mirror (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1975)

What are the limits of narrative cinema? If, indeed, The Mirror is narrative -- that question needs to be developed in more ways than I care to go into here. It's easy to say that Andrei Tarkovsky's film is non-linear, jumping back and forth in time with no clues about when and where we are in any given moment. Even the switches from black-and-white to color turn out to be red herrings if you're trying to sort out chronology. There is a fine line between frustration and stimulation, and Tarkovsky dances along it as we the viewers similarly traverse the line between ennui and involvement. It is, I gather from reading several essays that reinforce my impressions of the film, a memory piece in which Alexei, a man on his deathbed, recalls his childhood in Russia before, during, and after World War II. His memories include his mother, Maria, and his wife, Natalia, both played beautifully by Margarita Terekhova. Similarly, Ignat Daniltsev plays both the young Alexei and his son, Ignat. There are lucid episodes throughout the film, mixed with newsreel footage from the wartime and postwar periods, along with bits of fantasy and surrealism. I would like to say that The Mirror is hypnotic, because it begins with a scene in which a therapist uses hypnotism to try to cure a young man of a speech impediment, but that oversimplifies the effect of the film. I love and admire the previous Tarkovsky films I have seen -- Ivan's Childhood (1962), Andrei Rublev (1966), and Solaris (1972) -- but I will have to see it again to decide if I want to join the consensus on its greatness: It took 19th place in the 2012 Sight and Sound critics poll of the greatest films of all time, and an astonishing 9th place in the directors' poll. I concede that it is "poetic," including the fact that Arseniy Tarkovsky, the director's father, reads his own poems in the film, and there are scenes of extraordinary beauty, the work of cinematographer Georgi Rerberg. But is that all we should ask of a film?

Thursday, November 17, 2016

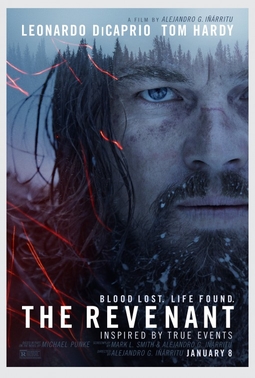

The Revenant (Alejandro González Iñárritu, 2015)

I have suggested before, in my comments on Birdman (2014), Babel (2006), and 21 Grams (2003), that in Alejandro G. Iñárritu's films there seems to be less than meets the eye, but what meets the eye, especially when Emmanuel Lubezki is the cinematographer, as he is in The Revenant, is spectacular. The Revenant had a notoriously difficult shoot, owing to the fact that it takes place almost entirely outdoors during harsh weather, and it went wildly over-budget. Leonardo DiCaprio underwent significant hardships in his performance as Hugh Glass, the historical fur trader who became a legend for his story of surviving alone in the wilderness after being mauled by a grizzly bear. In the end, it was a major hit, more than making back its costs and getting strong critical support and 12 Oscar nominations, of which it won three -- for DiCaprio, Lubezki, and Iñárritu. I won't deny that it's an impressive accomplishment, and probably the best of the four Iñárritu films I've seen. It's full of tension and surprises, and fine performances by DiCaprio; Tom Hardy as John Fitzgerald, the man who leaves Glass to die in the wilderness; and the ubiquitous Domhnall Gleeson as Andrew Henry, the captain of the fur-trapping expedition who aids Glass in his final pursuit of Fitzgerald. Lubezki's cinematography, filled with awe-inspiring scenery and making good use of Iñárritu's characteristic long tracking takes, fully deserves his third Academy Award, making him one of the most honored people in his field. The visual effects blend seamlessly into the action, especially in the harrowing grizzly attack. And yet I have something of a feeling of overkill about the film, which seems to me an expensive and overlavish treatment of a tale of survival and revenge -- great and familiar themes that have here been overlaid with the best that today's money can buy. The film concentrates on Glass's suffering at the expense of giving us insight into his character. It substitutes platitudes -- "Revenge is in God's hands" -- for wisdom. And what wisdom it ventures upon, like Glass's native American wife's saying, "The wind cannot defeat the tree with strong roots," is undercut by the absence of characterization: What, exactly, are Glass's roots?

Wednesday, November 16, 2016

O Brother, Where Art Thou? (Joel Coen and Ethan Coen, 2000)

On the scale for goofy Coen brothers films, O Brother, Where Art Thou? falls somewhere between Raising Arizona (1987) and The Big Lebowski (1998) from goofiest to least goofy. It is, I think, more over-the-top than is absolutely necessary, especially in the idiot hick accents adopted by John Turturro and Tim Blake Nelson in their roles. Or maybe they just seem that way because of the differently over-the-top performance of George Clooney as Ulysses Everett McGill, a man who thinks he talks more intelligently than he does. Still, I like Clooney in this mode, more than I do when he's playing a serious character, and it's to the Coens' credit that they cast him in the role: His performance gives an odd kind of off-balance stability to that of the other two. The chief glory of the movie, however, is its music, chosen by T Bone Burnett, superbly evoking a time and place. As for that time and place, Depression-era Mississippi, the movie pretty much ignores reality in favor of goofing around. It was the era of Bilbo and Vardaman, politicians of deeply cynical evil, and the rival candidates played by Charles Durning and Wayne Duvall don't even approach their horror, even when lampooning it. I laughed when the Ku Klux Klan performed what looked like a marching band half-time routine with a chant that evokes the parading monkey guards in The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming, 1939), but maybe it's the outcome of the recent presidential election that made me feel a little nauseated at even the notion of a comical Klan. A kind of irresponsibility mars the Coens' approach to the material, brilliantly funny as it often is. That said, the pacing of the movie is lively, and it's filled with ever-watchable performers like Durning, Holly Hunter, and John Goodman at their best. And there's always that music: If I'm inclined to forgive the Coens for their irresponsibility, it's because they introduced a lot of people who went out and bought the soundtrack album to some great music.

Tuesday, November 15, 2016

Children of Men (Alfonso Cuarón, 2006)

|

| Clive Owen in Children of Men |

Julian: Julianne Moore

Jasper: Michael Caine

Kee: Claire-Hope Ashitey

Luke: Chiwetel Ejiofor

Patric: Charlie Hunnam

Miriam: Pam Ferris

Syd: Peter Mullan

Nigel: Danny Huston

Marichka: Oana Pellea

Ian: Phaldut Sharma

Tomasz: Jacek Koman

Director: Alfonso Cuarón

Screenplay: Alfonso Cuarón, Timothy J. Sexton, David Arata, Mark Fergus, Hawk Ostby

Based on a novel by P.D. James

Cinematography: Emmanuel Lubezki

Production design: Jim Clay, Geoffrey Kirkland

Film editing: Alfonso Cuarón, Alex Rodríguez

Music: John Taverner

George Lucas did something shrewd when he prefaced his first Star Wars movie in 1977 with the phrase "A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away." Deliberately echoing the formulaic "Once upon a time," Lucas emphasized the fairy-tale essence of his science-fiction fable. But other creators of science fiction haven't been so careful, or perhaps have been more insouciant. George Orwell's 1984 was written in 1948, and all Orwell did was set the novel in a year that inverted the last two digits of the year of its completion. He wasn't presenting a literal forecast of actual life in the year 1984, he was serving as a prophet of what was actually present and nascent in his own time: totalitarianism and pervasive invasion of privacy. So 32 years later, we still find an uneasy resonance of Orwell's book in our own times. Similarly, when Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clark teamed to write the screenplay for 2001: A Space Odyssey (Kubrick, 1968), they weren't necessarily predicting deep exploration of the solar system and encounters with mysterious monoliths -- though I rather suspect they were hoping for at least the first -- but rather speculating on the origins of human nature and consciousness and their relationship to artificial intelligence. Similarly, the dystopian world of Blade Runner (Ridley Scott, 1982), populated by replicants and traversed by flying cars, is supposedly set in 2019 -- a year now close at hand -- but is also centrally concerned with the nature of humanity in a corporate capitalist society. What I'm getting at is that sometimes science fiction writers and filmmakers distance themselves as Lucas does from any notion that they're commenting on the "real world," but sometimes embrace a specific foreseeable date, with a view to making either a prediction of the way things will evolve or a comment on the problems of their own day. This is why I find Alfonso Cuarón's Children of Men such a puzzling film. It gives us a dank dystopian London that resembles the dank dystopian Los Angeles of Blade Runner, and it sets it in a specific time, the year 2027, a world in which human beings stopped bearing children 18 years earlier: i.e., in the year 2009 -- only three years after the film was made. But unlike Blade Runner, it doesn't seem to be telling us anything specific about either a predicted future or the way we lived then. It's a very entertaining film, full of violent action and suspense, with some wizardly work by Oscar nominees cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki and editors Cuarón and Alex Rodríguez. The way they handle the film's much-praised long-take sequences, aided by special effects to give the sense of complex action taking place in a single traveling shot, is exceptional -- anticipating Lubezki's work in making the entirety of Birdman (Alejandro González Iñárritu, 2014) seem to be a continuous take. There are also fine performances by Clive Owen, Julianne Moore, Chiwetel Ejiofor, Clare-Hope Ashitey, and the inevitably wonderful Michael Caine. But what is at the core of the film? Why does the failure of humankind to reproduce precipitate the worldwide cataclysm that the movie presents us? We have fretted so long about overpopulation that it would seem a blessing to have at least a pause in it, in which the world's scientists might take time to resolve the problem, or at least to discover the reason for the widespread infertility. Instead, we have a story that's largely about the mistreatment of immigrants. Why would non-reproducing immigrants, in a world with a declining population and therefore less pressure on natural resources, be a problem? Is it possible that this film, based on but radically altered from a novel by P.D. James, is promoting the extreme "pro-life" view, not only anti-abortion but also anti-contraception? Or is it simply that, as one character puts it, "a world without children's voices" is inevitably a terrible place? The film's failure to suggest a larger context for its action seems to me to by a weakness in an otherwise extraordinary film.

Monday, November 14, 2016

Pigsty (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1969)

Pier Paolo Pasolini's Pigsty is too much like what people think of when they hear the phrase "art house movie," especially when they have in mind films of the late 1960s. It's enigmatic and disjointed, and has a tendency to treat images as if they were ideas -- significant ideas. There are two narratives at work in the film: One features Pierre Clémenti as some kind of feral human wandering a volcanic landscape in which he finds a butterfly and a snake and eats both, then dons the helmet and musket he finds beside a skeleton. It's some unspecified pre-modern era -- the helmet and the garb of the soldiers and priests he meets later make think 17th century. He kills and eats another man he meets, then begins to gather a group of fellow cannibals. The other story takes place in Germany in 1967 and centers on Julian Klotz (Jean-Pierre Léaud), the son of a wealthy ex-Nazi (Alberto Lionello) who styles his hair and mustache like his late Führer and is pursuing a merger with a Herr Herdhitze (Ugo Tognazzi), who is a rejuvenated Heinrich Himmler, having undergone extensive plastic surgery. Julian, meanwhile, is an aimless youth who resists the urgings of his fiancée, Ida (Anne Wiazemsky) to join in leftist protest movements and to have sex with her. He'd rather spend time with the pigs in a nearby sty. The efforts at satire in the modern section are as heavy-handed as they sound in this summary, especially since Pasolini has chosen to have much of the exposition delivered by the actors in the flat-footed style of a 19th-century melodrama. There are some acting standouts, however, in both sections, especially Léaud, who seems to be having more fun than his role allows; Clémenti and Pasolini regular Franco Citti throw themselves into their feral roles, and Tognazzi is suavely menacing in his. If the whole thing is meant as a satire on dog-eat-dog (or man-eat-man or pig-eat-man) capitalism, it is sometimes too oblique and sometimes too blatant. Pasolini is a challenging, original filmmaker as always, but this one doesn't transcend the often inchoate artistic fervor of the '60s avant garde.

Sunday, November 13, 2016

In the Mood for Love (Wong Kar-wai, 2000)

In the British Film Institute's Sight and Sound critics' poll of the greatest films of all time, Wong Kar-wai's In the Mood for Love placed at No. 24, in a tie with Rashomon (Akira Kurosawa, 1950) and Ordet (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1955). I have to admit that I wouldn't rank it quite so high, especially putting it on a par with the other two films, but its intense, elliptical love story -- one in which there is no nudity, no sex scenes, and in fact not even a consummation of the affair -- is certainly unique and challenging. It's a film whose claustrophobic settings occasionally reminded me of the below-deck scenes in L'Atalante (Jean Vigo, 1934). The would-be lovers, Chow (Tony Leung Chiu-Wai) and Su Li-zhen (Maggie Cheung), are as trapped in their Hong Kong rooms as the newlyweds in L'Atalante are on their river barge, with the additional limitations that they are trapped in their marriages, in their offices, and in the social conventions of the 1960s. In one marvelous sequence she is trapped in his room when their landlady, Mrs. Suen (Rebecca Pan), comes home earlier than expected and then stays up all night playing mahjong with the neighbors, preventing her from leaving and adding fuel to the gossip but also fueling their intimacy. It's a masterstroke that we never see their respective spouses or even receive direct confirmation of what Chow and Su Li-zhen suspect: that her husband and his wife are having an affair with each other. They can't redouble the scandal by openly pairing off with each other, and in the end the paralysis becomes so ingrained in them that they are unable to consummate their relationship even when they are liberated from their claustrophobic living arrangements. Wong makes the most of the cinematography of Christopher Doyle and Mark Lee Ping-bin, framing them in the clutter of the offices where they work, focusing intensely on them as they meet in restaurants, using a variety of techniques such as slow motion and swish-pans, always with the effect of emphasizing their alienation. The score is often exquisitely appropriate, with themes by Michael Galasso and Shigeru Umebayashi as well as pop recordings by Nat King Cole and others. The historical references -- the tension evident in Hong Kong as it approaches the handover by Britain to China, a 1966 newsreel featuring Charles de Gaulle, Chow's final scene in Angkor Wat -- strike me as an unnecessary attempt to give the relationship of Chow and Su a connection to something larger than just a frustrated love affair. The story is poignant and resonant enough without them.

Saturday, November 12, 2016

The 47 Ronin (Kenji Mizoguchi, 1941)

|

| Chojuro Karawasaki in The 47 Ronin |

Friday, November 11, 2016

The Big Sleep (Howard Hawks, 1946)

|

| Humphrey Bogart and Martha Vickers in The Big Sleep |

Vivian Rutledge: Lauren Bacall

Eddie Mars: John Ridgely

Carmen Sternwood: Martha Vickers

Book Shop Owner: Dorothy Malone

Mona Mars: Peggy Knudsen

Bernie Ohls: Regis Toomey

Gen. Sternwood: Charles Waldron

Norris: Charles D. Brown

Lash Canino: Bob Steele

Harry Jones: Elisha Cook Jr.

Joe Brody: Louis Jean Heydt

Director: Howard Hawks

Screenplay: William Faulkner, Leigh Brackett, Jules Furthman

Based on a story by Raymond Chandler

Cinematography: Sidney Hickox

Art direction: Carl Jules Weyl

Film editing: Christian Nyby

Music: Max Steiner

I've cited Keats's "negative capability" before in warning about getting too involved with the literal details of a movie at the expense of missing the total effect, and it still seems appropriate here when it comes to figuring out exactly who did what to whom in Howard Hawks's The Big Sleep. Screenwriters William Faulkner, Leigh Brackett, and Jules Furthman are said to have consulted Raymond Chandler, the author of the novel they were adapting, about certain obscurities of the plot, and Chandler admitted that he didn't know either, which is as fine an example of being "in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason" as even Keats could come up with. So ask not who killed the Sternwoods' chauffeur, or even who really killed Shawn Regan -- if, in fact, Regan is dead. This is one of the most enjoyable of films noir, if a movie that has so many sheerly pleasurable moments can really be called noir. It's also one of the most deliciously absurd -- or maybe absurdist -- movies ever made, including its persistent presentation of Humphrey Bogart's Philip Marlowe as an irresistible hunk, who has bookstore clerks, hat check girls, waitresses, and female taxi drivers swooning at his presence. The only thing that makes this remotely credible is that Lauren Bacall, and not just Vivian Sternwood Rutledge, actually did. In his review for the New York Times, Bosley Crowther, one of the most obtuse critics who ever took up space in a newspaper, called it a "poisonous picture" and commented that Bacall "still hasn't learned to act" -- an incredible remark to anyone who has just watched her exchange with Bogart ostensibly about horse racing. This is, of course, one of Howard Hawks's greatest movies, and of course it received not a single Oscar nomination -- not even for Martha Vickers's delirious Carmen Sternwood. Vickers was so good in her role that her part had to be trimmed to put more focus on Bacall, who was being groomed for stardom. Sadly, Vickers never found another role as good as Carmen. Dorothy Malone, who did go on to stardom and an Oscar, steals her scene as the bookstore owner amused and aroused by Marlowe's charisma. And then there's Elisha Cook Jr. as a small-time hapless hood not far removed from the Wilmer who stirred Sam Spade's homophobia in The Maltese Falcon (John Huston, 1946). Except this time his demise elicits something Marlowe would seem otherwise incapable of: pity.

Monday, November 7, 2016

Excuses, Excuses

I watched Samurai Rebellion (Masaki Kobayashi, 1967) last night, but I'm not going to write about it today because I'm facing a deadline for a book review. Back with more posts after that's done.

Sunday, November 6, 2016

The Great Beauty (Paolo Sorrentino, 2013)

The great beauty referred to in the title of Paolo Sorrentino's film is Rome itself, which for millennia has transcended the ugliness that has overrun its seven hills. It's a city whose beauty and ugliness are seen in the film from the point of view of Jep Gambardella (Toni Servillo), who is celebrating his 65th birthday as the film begins. Jep first received acclaim 40 years earlier for a well-received novella, but the rest of his life has been spent as a celebrity journalist, interviewing and gossiping about the rich and famous. This career has earned him his own fame and fortune -- he lives in a luxurious apartment whose balcony overlooks the Colosseum. He's a bit like a straight Roman Truman Capote. The Rome in which Jep moves is filled with absurdity and excess: a performance artist who runs headlong into an ancient aqueduct; a little girl who has made millions by splashing canvases with paint and then smearing and tearing at them in a tantrum; a doctor who maintains a kind of assembly-line botox clinic in which patrons take numbers as if they were waiting in a delicatessen; a saintly centenarian Mother Teresa-style missionary whose spokesman is an oily dude with a shark-toothed grin; an archbishop considered next in line for the papacy who can only talk about food; and hordes of glitterati who spout inanities that they think will pass for wit. The Great Beauty is a satire, of course, but oddly it's a satire with heart: Jep Gambardella's long-since-broken heart. Servillo is terrific in the key role: elegant and cynical, but also capable of exposing idiots for what they are. Jep and the film in which he appears have obviously been compared to Marcello Mastroianni's character in La Dolce Vita (Federico Fellini, 1960), but Jep is less jaded than Marcello, less ground down by the decadence. And Sorrentino's view of his Rome is more genially ironic than Fellini's carnival of grotesques. Beautifully filmed by Luca Bigazzi, with a score by Lele Marchitelli augmented with works by contemporary composers like David Lang, Arvo Pärt, John Taverner, Henryk Górecki, and Vladimir Martynov, The Great Beauty was a deserving winner of the 2013 Oscar for foreign-language film.

Saturday, November 5, 2016

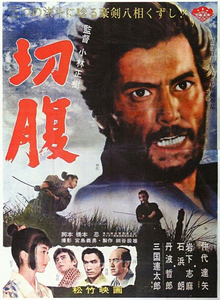

Harakiri (Masaki Kobayashi, 1962)

A study in tragic irony, Harakiri was intended as a commentary on Japan's history of hierarchical societies, from the feudal era through the Tokugawa shogunate and down to the militarism that brought the country into World War II and finally the corporate capitalism in which the salaryman becomes the latest iteration of the serf, pledging fidelity to a ruling lord. Working from a screenplay by Shinobu Hashimoto from a novel by Yasuhiko Takiguchi, director Masaki Kobayashi sets his film on a steady pace that at first feels static. There are long scenes of talk, with little moving except the camera's slow pans and zooms. But as Kobayashi's protagonist, Hanshiro Tsugumo (brilliantly played by Tatsuya Nakadai), tells his harrowing tale of loss, the film opens out into beautifully crafted scenes of action, as well as one terrifying and painful scene of cruelty, in which a man is made to commit the title's ritual disembowelment with a sword made of bamboo. Although there is an extended fight sequence in which Hanshiro takes on the entire household of the Ii clan, the true climax of the film is the duel between Hanshiro and Hikokuro Omodaka (Tetsuro Tanba), the greatest swordsman in the Ii household. Especially in this scene, the cinematography of Yoshio Miyajima makes a brilliant case for black and white film, aided by the editing of Hisashi Sagara that cuts between the dueling men and the waving grasses on the windswept hillside where the fight takes place. Harakiri is one of the best samurai films ever made, but even that observation contains its own note of irony, since Kobayashi's aim with the film is to validate his protagonist's assertion that "samurai honor is ultimately nothing but a façade."

Friday, November 4, 2016

A War (Tobias Lindholm, 2015)

|

| Pilou Asbæk in A War |

Maria Pederson: Tuva Novotny

Martin R. Olsen: Søren Malling

Kajsa Danning: Charlotte Munck

Najib Bisma: Dar Salim

Lasse Hassan: Dulfi Al-Jabouri

Director: Tobias Lindholm

Screenplay: Tobias Lindholm

Cinematography: Magnus Nordenhof Jønck

A war movie that appeals more to the brain and the heart than to the viscera, Tobias Lindholm's A War raises some haunting ethical questions about war and justice. Claus, a Danish officer, while leading a detachment of his men in an assault on the Taliban, calls in an air strike on what he believes to be the source of the gunfire that has pinned them down and left one of his soldiers critically injured. Under cover of the bombing they are able to make it to the rescue helicopter, but Claus is later charged with a war crime: There is no evidence that the gunfire came from the village where the bombing killed civilians, women and children. At the trial, held back in Denmark, Claus is acquitted after one of his men perjures himself, claiming that he had seen a muzzle flash from the village, justifying Claus's decision. But it's not a "happy ending." The film has provided many emotional justifications for Claus's action: We earlier saw Lasse, the critically injured man whose life Claus saves by calling in the air strike, in extreme emotional distress after witnessing the death of one of his fellow soldiers who stepped on a land mine. Claus had comforted Lasse, but nevertheless insisted that he go on this near-fatal mission. Claus also struggles with guilt because he had turned away an Afghan family seeking refuge in the military compound: They had been threatened by the Taliban after they sought medical help for their little girl, suffering from a bad burn. Reconnoitering for the assault, Claus discovers that the Taliban had made good on their threat and slaughtered the family. Claus is also struggling with pressure from home, where his wife, Maria, is having trouble looking after their three small children: The middle child is acting out at school, and the youngest, a toddler, has had to have his stomach pumped after swallowing some pills. Writer-director Lindholm beautifully balances the combat scenes with those depicting Maria's difficulties at home. But he also stages a fine courtroom scene in which the prosecutor demonstrates that Claus is in fact guilty as charged: There was no evidence that the destroyed village was the source of the gunfire that pinned down Claus and his men. So, even though his acquittal comes at the expense of a witness's lie, are we right to feel good that Claus is free and able to look after his family? There are hints that Claus will never be free of the burden of guilt: After the verdict, he is seen tucking in his children at night. The feet of one of the children are sticking out from under the covers, and Claus carefully pulls the blanket over them. It's a moment that echoes the earlier scene in which Claus discovered the slaughtered Afghan family: One of the dead children's feet were protruding from the covers just like Claus's own child's. Lindholm beautifully trusts the audience to recall this detail, without having Claus flash back to it himself, but the final scene of the film, in which Claus sits alone on his patio, smoking, suggests that he will always be alone with his guilt.

Thursday, November 3, 2016

The Navigator (Donald Crisp and Buster Keaton, 1924)

Buster Keaton always makes me grin. The first time I did it while watching The Navigator was when rich twit Rollo Treadaway (Keaton) puts on a straw hat and then gracefully steadies it with the crook of his cane. Keaton can do more with a hat -- or, later, hats -- than anyone, even Cary Grant with the outsize hat in my favorite scene in The Awful Truth (Leo McCarey, 1937). And then the grin became a guffaw when Rollo gets in his chauffeur-driven limousine to go propose to Betsy O'Brien (Kathryn McGuire), another rich twit. The limo starts out and immediately makes a U-turn to the other side of the street, where Betsy lives. It's not just Keaton's physical grace and dexterity, for all that he pretends to be a klutz, or even the unexpectedness of some of the gags that make me so happy. It's primarily the sense of joy I get in watching a kid play with his toys. For Keaton has such wonderful toys in his movies. In The General (Keaton and Clyde Bruckman, 1926) he has an entire antique railroad train to play with (and destroy); in Go West (Keaton, 1925) it's a herd of cattle; in Steamboat Bill Jr. (Charles Reisner but really Keaton, 1928) it's a town in a terrific windstorm. So you can imagine his delight when he heard than a retired Army transport ship was for sale, and he could refit this enormous toy into the cruise ship Navigator and do with it as he pleased. And he certainly made the most of it, using the exposed decks and corridors for a hilarious game of unwitting hide-and-seek between Rollo and Betsy, turning the galley into an improbable kitchen for two rich twits who have never had to cook their own breakfast, and donning an old-fashioned diving suit for an extended underwater sequence: Keaton does the only pratfall I've ever seen anyone do underwater and in a diving suit, legs straight out as all the great slapstick comics did pratfalls. There are some occasional slow moments: The battle with the "cannibals" goes on much too long. But the pacing mostly stays so rapid that you want to rewind and watch some scenes to see what you miss -- a luxury denied his original audiences, who had to stay and sit through it twice. McGuire also appeared in Keaton's Sherlock Jr. (1924), proving herself what any of Keaton's leading ladies had to be: game for almost anything, including repeated dives and dunkings. Although Donald Crisp, better known to us as an actor, was an experienced director -- he has 72 IMDb directing credits from 1914 through 1930 -- he turned out to be a mismatch with Keaton, who took over and finished the film, sometimes reshooting scenes that Crisp had directed.

Wednesday, November 2, 2016

Oedipus Rex (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1967)

Seeing Julian Beck as Tiresias in Pier Paolo Pasolini's Oedipus Rex reminded me of an excruciatingly boring evening I spent in Brooklyn in 1968. Some friends had invited me to go with them to see Beck's Living Theatre perform their play Paradise Now, which as I recall featured the semi-naked company, including some pale and pimply dudes in jockstraps, wandering through the audience, yelling at us about our bourgeois complacency. Those who know me will realize that this is not my sort of thing at all. I realize now that Beck and Judith Malina had a tonic effect on theater with their avant-garde productions, and I salute them for that, but I was not receptive to their efforts on that evening. Fortunately, Pasolini's Oedipus, though infused with some of the radicalism of the Living Theatre, is not at all boring. It's sometimes raw and rough-edged, especially by standards of mainstream cinema. The Technicolor camerawork -- the cinematographer is Giuseppe Ruzzolini -- is often very beautiful, with its astonishing images of the Moroccan desert and ancient buildings, but there are some bobbles in the hand-held camera sequences that move beyond shakycam into wobbly-out-of-focuscam. Franco Citti, who made his debut in the title role of Pasolini's Accattone (1961) and appeared in many of his other films, is a bit out of his depth as Oedipus, but Silvana Mangano is an impressive-looking Jocasta, and Beck is a suitably foreboding Tiresias. Pasolini's screenplay does justice to its Sophoclean origins as well as to the perdurable myth, although the frame story that begins in Italy during the Mussolini era, with the Fascist anthem "Giovinezza" on the soundtrack, and ends in Pasolini's present seems extraneous. But the truly astonishing contribution to the film was made by costume designer Danilo Donati, whose eerie designs, seemingly cobbled together from scrap metal, clay, and leaves and branches, don't belong to any particular era but have the right aura of primitive myth. Some examples:

|

| The Oracle of Apollo in Oedipus Rex |

|

| Silvana Mangano as Jocasta |

|

| Headdress for a priest |

Tuesday, November 1, 2016

Star Wars: Episode VII -- The Force Awakens (J.J. Abrams, 2015) revisited

When I blogged about seeing Star Wars: Episode VII -- The Force Awakens, to give it its full and exhausting title, 10 months ago, I was more involved in the novelty of seeing it in a theater and in 3-D than in commenting on the film itself. "I look forward to seeing the movie again, but this time in the comfort of my home and on a smaller 2-D screen," I said then, predicting that it would "play just as well there." So the time has come, and Starz is running it almost every day on one of its many channels, so I availed myself of the opportunity, and I think I was mostly correct. The flat version is less awe-inspiring than the three-dimensional one, but I've long since got beyond the excitement of having lightsaber beams waved in my face, and to my mind the added depth of the images is counteracted by a sense of their insubstantiality: Is it only the force of long habit and familiarity that makes two-dimensional films seem more like documented reality? The 2-D Episode VII stands up because J.J. Abrams knows the grammar of film: the cutting and pacing that has brought excitement to movies ever since Griffith and Eisenstein and other first learned to use them. In 3-D there's always going to be something a little disorienting about the shift from a close-up to a long shot, for example. Perhaps a grammar of 3-D will be developed that lets filmmakers use it as effectively as they do in two dimensions, but that time has yet to come. As for the film itself, it had to do two things: It had to tie the new material to the core trilogy -- I mean Episodes IV-VI, of course -- and it had to whet our appetites for more new stuff. It succeeds on both counts, partly by bringing back Han (Harrison Ford), Leia (Carrie Fisher), and, albeit briefly, Luke (Mark Hamill), and the leitmotifs of John Williams's score, but also by pretty much shamelessly borrowing from what's now called Star Wars: Episode IV -- A New Hope (George Lucas, 1977). (I will always call it just Star Wars.) As I said in my first post, VII is pretty much a remake of IV: Both have "the young hero on a desert planet, the messenger droid found in the junkyard, the gathering of a team to fight the black-clad villain, and the ultimate destruction of a giant weaponized space station." VII also echoes the Oedipal conflict of the subsequent episodes of the core trilogy, with the conflict of father Han and son Kylo Ren (Adam Driver) echoing that of Darth Vader and Luke. What we have to look forward to is some account of Ren's (or Ben's) fall to the Dark Side and some resolution of that character's patricidal act. We also have to find out who or what Supreme Leader Snoke (Andy Serkis) is. Is there a little old man lurking behind what seems to be a hulking hologram, like the Wizard of Oz? And what are the backstories of Poe Dameron (Oscar Isaac), Finn (John Boyega), and Rey (Daisy Ridley)? And what accounts for the luxury casting of the ubiquitous Domhnall Gleeson as the relatively secondary figure General Hux? And why waste a beautiful Oscar winner like Lupita Nyong'o in voicing Maz Kanata -- another character whose backstory needs to be told? So our appetites are whetted, and not just for further adventures of Luke Skywalker.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.png)

.jpg)