A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Friday, November 27, 2015

The Flowers of St. Francis (Roberto Rossellini, 1950)

After his great Neo-Realist films Rome, Open City (1945) and Paisan (1946), and just as he was beginning his relationship with Ingrid Bergman, Rossellini made this sweet-natured film that combines some of his Neo-Realism (the use of non-professional actors) with some of the moral questioning he does in the four Bergman films, especially Europe '51 (1952). Based on two 14th-century books that retold legends of the life of St. Francis and his followers, The Flowers of St. Francis consists of a prologue and nine episodes. The actors, who were Franciscan monks, are not credited, although Francis was played by Brother Nazario Gerardi and the key role of Brother Ginepro by Brother Severino Pisacane. The only professional actor in the film is Aldo Fabrizi, who had worked with Rossellini in Rome, Open City. Fabrizi is the monstrous tyrant Nicolaio, who torments Ginepro until he is won over by the monk's gentle endurance of all the ills inflicted on him -- at one point, Ginepro is used as a human jump rope, then dragged around Nicolaio's camp behind a horse. The title of the film in Italian is Francesco, Giullare di Dio, meaning "God's jester," and the moral lesson constantly taught in the film is that of self-abasement to the point of ridicule. In a key episode, Francis and another friar go in search of perfect happiness. They find it when they go to the house of a man who repeatedly refuses their plea for alms until he finally beats them and kicks them downstairs. Then Francis explains that true happiness is to suffer in the name of Christ, a moral lesson not unlike the one learned by Irene Girard (Bergman) in Europe '51, where it's expressed in more secular terms. (And one that I might use as an excuse the next time I shut the door on a Jehovah's Witness or a Mormon missionary.) The screenplay was written in collaboration with Federico Fellini with consultation from two Roman Catholic priests, though the film is much lighter in tone than that suggests.

Thursday, November 26, 2015

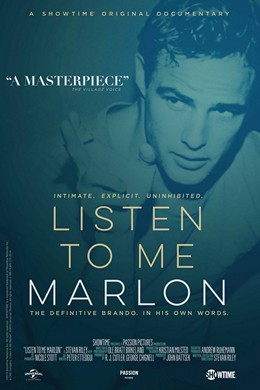

Listen to Me Marlon (Stevan Riley, 2015)

It's a truism that Marlon Brando revolutionized film acting. (With a little help from Montgomery Clift and James Dean, and some pioneering by John Garfield.) And it seems that Brando believed the truism himself: At one point in this fascinating documentary he disses such older film stars as Gary Cooper, Clark Gable, and Humphrey Bogart, asserting that they were always the same in their movies. This misses the point about film stardom, I think, which is that everyone who gets established as a film actor carries their image from movie to movie. How much variety, really, is there in Brando's most memorable film performances? Stanley Kowalski in A Streetcar Named Desire (Elia Kazan, 1951), Johnny Strabler in The Wild One (Laslo Benedek, 1953), Terry Malloy in On the Waterfront (Elia Kazan, 1954), and even Vito Corleone in The Godfather (Francis Ford Coppola, 1972) and Paul in Last Tango in Paris (Bernardo Bertolucci, 1972) are all troubled urban Americans with a rebellious streak. And when Brando tried to break away from that type -- as Emiliano Zapata in Viva Zapata! (1952), Mark Antony in Julius Caesar (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1953), Napoleon in Désirée (Henry Koster, 1954), or Fletcher Christian in Mutiny on the Bounty (Lewis Milestone, 1962) -- the performances leave a lot to be desired. Mind you, I still think Brando was one of the greatest actors in film history, but only when he let himself play roles that suited him -- as Cooper, Gable, and Bogart did. This film, which uses Brando's own tape recordings as its principal source, shows him as a kind of tragic naïf in search of something that would heal the wounds he carried from childhood. He found it in acting when he fell under the spell of Stella Adler, although the Adler shown in this film is given to talking pretentious nonsense about how acting isn't about the words, it's about the soul. Brando also sought healing in sex, in psychoanalysis, in political activism, but the picture that emerges in the film is of a man who never succeeded in escaping his own tormented ego.

Wednesday, November 25, 2015

Some Like It Hot (Billy Wilder, 1959)

Twenty years ago (!), when I wrote my book about movies that had been nominated for Oscars, I had this to say about Some Like It Hot: "Hilarious farce and one of the sweetest natured of Wilder's usually acerbic comedies, thanks to endearing performances by [Jack] Lemmon and [Joe E.] Brown, [Tony] Curtis' high-spirited mimicry of [Cary] Grant, and [Marilyn] Monroe's breath-taking luminosity." Today, after all we've learned about sexual orientation and identity, after many feminist critiques of Hollywood's depiction of women, and after many explorations of Monroe's tragic history, that comment sounds a little naive. Plumb beneath the surface of what seems to be mere entertainment and you'll find disturbance in the depths. Take the celebrated ending of the film, for example. Sugar (Monroe) gets Jerry (Curtis), but at what price? As he warns her, he's exactly the kind of guy she knows is bad for her. And Osgood's (Brown) shrugging off the fact that Daphne (Lemmon) is a man is one of the funniest moments on film, but in fact, the two men have the kind of chemistry together (as in the tango scene) that works, whereas Curtis and Monroe have no real chemistry. Is the film making a case, well in advance of its time, for same-sex attraction? Probably not Wilder's conscious intention, but what does that matter? As for the difficulties of working with Monroe that Wilder and her co-stars later complained about -- though Curtis eventually retracted the much-quoted (including by me) statement that kissing her was "like kissing Hitler" -- this remains perhaps her best film and best performance. Imagine the movie with Mitzi Gaynor (originally thought of for the part and on standby in case Monroe bailed on it) and you have nothing like the one we now know. In lesser hands than Wilder's the clichés (men in drag on run from gangsters) would have resulted in a second-rate comedy. The real marvel is that Wilder produced something enduring out of clichéd material. Curtis and Lemmon are great, even though their roles are the traditional comic teaming of a bully (Curtis) and a patsy (Lemmon), the formula already worked over by Laurel and Hardy, Abbott and Costello, Bing Crosby and Bob Hope, and Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis. Sometimes what you have to do is take the formula and transcend it.

Tuesday, November 24, 2015

The Seven Year Itch (Billy Wilder, 1955)

Tiresome, talky, and unfunny, this may be Billy Wilder's worst film. Wilder blamed the censors, who squelched all the sexual innuendos that he wanted to carry over from David Axelrod's Broadway play. In the play, the protagonist, whose wife and child have gone to Maine to escape the summer heat in Manhattan, has an affair with the young woman who lives upstairs. The censors insisted that they must remain chaste: She spends the night in his apartment, sleeping in his bed while he spends a restless night on the sofa. The lead of the play, the saggy-faced character actor Tom Ewell, was retained for the film, while the biggest female star of the day, Marilyn Monroe, was cast opposite him. The result is a sad imbalance: Ewell, who is on-screen virtually all 105 minutes of the movie, is allowed to overplay the role as if performing to the rear of the balcony. Monroe, whose role is considerably shorter, works hard at giving some substance to her character, though it's little more than the ditzy blonde she had begun to resent having to play. And the match-up of Ewell and Monroe is entirely implausible. (On stage, the part was played by the pretty but decidedly un-Marilynesque Vanessa Brown.) The film is remembered today chiefly for the scene in which Monroe stands on a subway grate and her dress is blown up by train passing below.

Monday, November 23, 2015

The Night of the Hunter (Charles Laughton, 1955)

Is there another great film so inconsistent in tone and technique? For it is a great film for the most part -- certainly every part that features Robert Mitchum in one of the defining roles of his career. And the central section that deals with the river journey of the two children, John (Billy Chapin) and Pearl Harper (Sally Jane Bruce), has a mythic resonance, enhanced by Lillian Gish's marvelously naive retelling of the stories of Moses in the bulrushes and the flight of the Holy Family from Herod's massacre of the innocents. Director Laughton, cinematographer Stanley Cortez, and art director Hilyard M. Brown give us memorable images like that of the drowned Shelley Winters, hair floating like the underwater weeds, or the one of Mitchum on horseback silhouetted in the distance against the night sky as the terrified children cower in a barn. I particularly love one heart-stopping moment: Lillian Gish has been sitting on her screened porch, shotgun on her lap, protecting the children while Mitchum waits outside. Gish and Mitchum have both been singing the hymn "Leaning on the Everlasting Arms" in an ironically peaceful duet. Then a child brings a candle to the porch and its light is reflected on the screen for a moment, hiding Mitchum from Gish's view. She quickly blows out the candle, but by the time she does, he has disappeared. If Laughton had been able to sustain this sort of tension throughout the film, it would be easier to call The Night of the Hunter a masterpiece. But some of his work is undone by the intrusive score by Walter Schumann. And Laughton, in his only film as director, isn't able to bring off what should be the film's climax: the capture, trial, and threatened lynching of Mitchum's character. As staged and edited, it proves anticlimactic. Nor does the Christmasy happy ending succeed in avoiding sentimentality. Some of the film's flaws no doubt result from the screenplay by James Agee, much revised by Laughton, which occasionally works too hard at being "poetic." But it's criminal that the poor initial reception of the film discouraged Laughton from trying his hand as director again.

Sunday, November 22, 2015

Bombshell (Victor Fleming, 1933)

This giddy screwball comedy is one of the earliest examples of the genre, with a screenplay by John Lee Mahin and Jules Furthman that's wall-to-wall wisecracks and frantic antics. It also has more sexual innuendo than later examples of the genre, since it was released a year before the Production Code began to be enforced by the notoriously blue-nosed Joseph Breen. There's even a joke about the censors in the script, in which the movie star played by Jean Harlow is being called on for retakes on Red Dust (1932), because of objections from the Hays Office, the code's precursors. (Mahin wrote the screenplay for Red Dust and Fleming directed it.) The cast is peerless: Harlow plays Lola Burns, a star said to be modeled on Clara Bow, and Lee Tracy is her hyperactive press agent "Space" Hanlon. Tracy has a way of exploding into rooms that reminds me of Kramer on Seinfeld. Fleming was probably not the ideal director for this fast-paced nonsense, which deserves a looser, lighter touch like that of Ernst Lubitsch or Howard Hawks, but he gives his cast freedom and they're equal to the challenge. Watch the ensemble, for example, demonstrate perfect comic timing in some of the scenes that Fleming films in long takes. Even Franchot Tone, one of the more forgettable leading men of the 1930s, demonstrates unexpected comic skill in the scene in which, as the phony Boston socialite Gifford Middleton, he woos Lola with lines like "I'd like to run barefoot through your hair." Also on hand is Louise Beavers, playing a maid of course, in an exchange that wouldn't get by Breen a year later: When Harlow asks what happened to the negligee she gave her, Beavers replies that "it got all tore up night before last." Harlow observes, "Your day off is sure brutal on your lingerie."

Saturday, November 21, 2015

Their Own Desire (E. Mason Hopper, 1929)

Two years before A Free Soul, Norma Shearer made this rather thin talkie, which shows clearly her evolution from silence into sound. She hasn't yet found her voice level: It was only her third talking picture and she still sounds a bit thin, and her laugh is a little shrill. It probably helped that her brother, Douglas Shearer, was the head of MGM's sound department, and could help her get the right pitch, because her next film, The Divorcee (Robert Z. Leonard, 1930), won her the best actress Oscar. (In fact, the Oscar ballot listed her nomination as for both The Divorcee and Their Own Desire, but the official citation showed her as a winner for only the former. Academy record-keeping was primitive at the time, so no one today knows if the voters indicated a preference for the one film over the other -- as they should have, since her performance in The Divorcee is indeed the better one.) In Their Own Desire, Shearer is playing a post-flapper "new woman," lively and athletic: She plays polo, taking a spill from a horse with no ill effects, and gets the attention of men by doing high dives into the country club pool. The man she attracts is played by Robert Montgomery, who was two years younger than 27-year-old Shearer, and both are convincingly coltish in their infatuation. The plot, from a novel by Sarita Fuller adapted by Frances Marion, is pleasantly nonsensical: Shearer and Montgomery fall in love, not knowing that he is the son of the woman (Helene Millard) whom her father (Lewis Stone) has divorced her mother (Belle Bennett) to live with. (The movie was made, obviously, before the institution of the Prohibition Code's proscription on such goings-on.) It's complicated, as they say. MGM made the most of its entry into sound, including two musical numbers: the songs "Blue Is the Night," played during a dance at the country club, and "The Boyfriend Blues," sung to Shearer by a harmonizing quartet. Director Hopper had been making movies since 1911, but he retired from the business in 1935, leaving an oeuvre of no particular distinction though he lived on till 1967.

Friday, November 20, 2015

A Free Soul (Clarence Brown, 1931)

|

| Clark Gable and Norma Shearer in A Free Soul |

Dwight Winthrop: Leslie Howard

Stephen Ashe: Lionel Barrymore

Ace Wilfong: Clark Gable

Eddie: James Gleason

Director: Clarence Brown

Screenplay: John Meehan, Becky Gardiner

Based on a novel by Adela Rogers St. Johns and a play by Willard Mack

Cinematography: William H. Daniels

Art director: Cedric Gibbons

Costume design: Adrian

Norma Shearer made the transition to talkies easily: She had a well-placed voice and, when the role called for it, a natural way of handling dialogue. Unfortunately, A Free Soul doesn't call for much in the way of "natural" for Shearer, and it's one of the films that suggest why, of the major female stars of the 1930s (Garbo, Crawford, Loy, Harlow, Stanwyck, Dietrich, Hepburn, Colbert), she is the least remembered. She works hard at her role as the free-spirited daughter of an alcoholic defense attorney, but too often her work is undone by a tendency, perhaps carried over from silent films, to strike mannered poses: typically, hands on hips, shoulders back, chin high. She looks great, however, in the barely-there gowns designed for her by Adrian, which seem to be held in place by will power (or double-sided tape). The plot calls on her to try to dry out her drunken father by wagering that if he can sober up, she'll give up her relationship with the sexy gangster her father managed to save from a murder rap. That gangster is played by Clark Gable, who got fifth billing (after James Gleason!), a sign of his status at the time. Gable had been making movies, usually in bit parts, since 1923, but this was the film that catapulted him, at age 30, into stardom. He still stands out in the movie as a natural, unaffected presence amid the mannered Shearer, hammy Lionel Barrymore, and pasty-looking Leslie Howard. It doesn't even hurt Gable that he's cast as a heel named Ace Wilfong, which brings to mind the insurance salesman in It's a Gift (Norman Z. McLeod, 1934) who annoys W.C. Fields with his search for Carl LaFong, "Capital L, small a, capital F, small o, small n, small g. LaFong. Carl LaFong." The improbable story comes from a novel by Adela Rogers St. Johns that had been adapted into a play by Willard Mack. (Incidentally, the play had been directed on Broadway in 1928 by George Cukor and starred Melvyn Douglas as Ace Wilfong.) Barrymore won the best actor Oscar on the strength of the courtroom speech he gives at the film's end. Barrymore claimed that he did it in one take with the help of multiple cameras, but the logistics of lighting for that many cameras makes his story hard to credit.

The Blackbird (Tod Browning, 1926)

The Blackbird begins with an atmospheric re-creation of Victorian Limehouse, with set designs by Cedric Gibbons and A. Arnold Gillespie impressively lighted and shot by cinematographer Percy Hilburn. But it turns into a routine melodrama showcase for Lon Chaney, who plays both the title character, a thief, and his alter ego, the Bishop, who pretends to be a missionary in the district. No one seems to suspect that the Blackbird and the Bishop are the same person, because in the latter persona Chaney contorts himself, holding one shoulder higher than the other and twisting one leg into an impossible position. Eventually, this masquerade will prove the truth of your mother's adage that if you keep contorting your face or body like that, it'll freeze that way. But in the meantime, the Blackbird falls for a music hall performer, Fifi Lorraine (Renée Adorée), who is also being pursued by a society toff (Owen Moore) known as West End Bertie. He's a thief, too, but in his case love for Fifi proves stronger than larceny. Browning, who also wrote the story (with Waldemar Young), handles this nonsense well. Adorée is charming, and her slightly risqué puppet show is fun, but the only real reason to see this movie is to admire Chaney's unfailing commitment to his considerable art.

Thursday, November 19, 2015

Blade Runner (Ridley Scott, 1982)

Rick Deckard: Harrison Ford

Roy Batty: Rutger Hauer

Rachael: Sean Young

Gaff: Edward James Olmos

Bryant: M. Emmet Walsh

Pris: Daryl Hannah

J.F. Sebastian: William Sanderson

Zhora: Joanna Cassidy

Director: Ridley Scott

Screenplay: Hampton Fancher, David Webb Peoples

Based on a novel by Philip K. Dick

Cinematography: Jordan Cronenweth

Production design: Laurence G. Paull

Film editing: Marsha Nakashima, Terry Rawlings

Music: Vangelis

I had forgotten that Blade Runner, with its flying cars, ads for Atari and Pan Am, and rainy Los Angeles, was set in the year 2019, which unless things change radically in the next four years puts it on a par with 1984 (Michael Anderson, 1956) and 2001 (Stanley Kubrick, 1968) for missed prognostications. Yet despite this, and even more despite the great advances in special effects technology, this 33-year-old movie hardly feels dated. That's because it isn't over-infatuated with the technological whiz-bang of so many sci-fi films, especially since the advances in CGI. Its effects, supervised by the great Douglas Trumbull, have the solidity and tactility so often missing in CGI work, because they're very much in service of the vision of production designer Laurence G. Paull, art director David L. Snyder, and especially "visual futurist" Syd Mead. But more especially because they're in service of the humanity whose very questionable nature is the point of Hampton Fancher and David Webb Peoples's adaptation of the Philip K. Dick novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? It also helps that the film has a terrific cast. Harrison Ford can't help bringing a bit of Han Solo and Indiana Jones to every movie, but it's entirely appropriate here -- one time when a star image doesn't fight the script. Rutger Hauer makes Roy Batty's death scene memorable, and even Sean Young, a problematic actress at best, comes off well. (I think it's because when we first see her, she's dressed and coiffed like a drag-queen Joan Crawford, so that when she literally lets her hair down she takes on a softness we're not accustomed to from her.) And then there's Edward James Olmos as the enigmatic origamist Gaff, Daryl Hannah, William Sanderson, and especially Joanna Cassidy, who manages to achieve poignancy even wearing a transparent plastic raincoat. I only wish that HBO would scrap its print of the "voice-over" version of the film, with Ford's sporadic narrative and the happy ending demanded by Warner Bros., and show director Scott's 2007 "Final Cut" version instead.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)