A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Friday, February 19, 2016

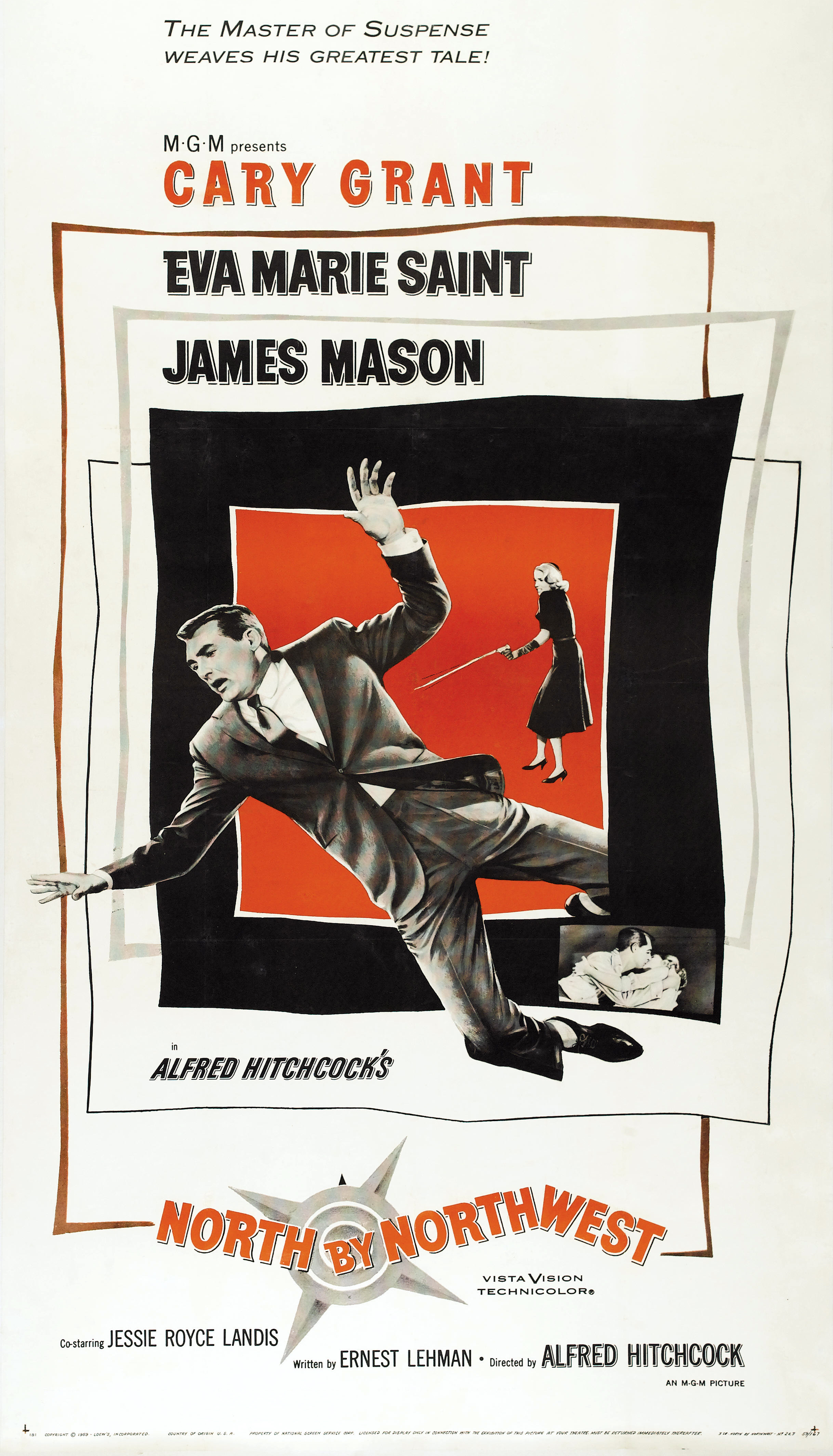

North by Northwest (Alfred Hitchcock, 1959)

There's a famous gaffe in North by Northwest, in the scene in which Eve Kendall (Eva Marie Saint) shoots Roger Thornhill (Cary Grant). Before she fires the gun, you see a young extra in the background stop his ears against the noise, even though it's supposed to surprise and panic the crowd. It's so obvious a mistake that you wonder how the editor, George Tomasini (who was nominated for an Oscar for the film), could have missed it. The usual explanation is that he couldn't find a way to cut it out, or didn't have footage to replace it. And after all, in the days before home video, would the audience in the theater notice? Even if they did, they would have no easy way to confirm that they had actually seen it. But I have a different suspicion: I think that they showed the goof to Alfred Hitchcock, and that he laughed and left it in. For above all else, North by Northwest is a spoof, a good-natured Hitchcockian jest about a genre that he had virtually invented in 1935 with The 39 Steps: the chase thriller, in which the good guy finds himself on the run, pursued by both the bad guys and other good guys. The ear-plugging kid fits in with the film's general insouciance about plausibility. A couple who climb down the face of Mount Rushmore, she in heels (and later in stocking feet) and he in street shoes? A lavish modern house with a private air strip that seems to be on top of the mountain, only a few hundred yards from the monument? A good-looking man who seems to go unnoticed by the crowds in New York and Chicago and on the train in between, even though his face is on the front page of every newspaper? A beautiful blond woman who shows up just at the right moment to take him in and not only hide him on the train but make love to him? Only a director with Hitchcock's skill and aplomb could take on such a tall tale and make it work, keeping you thoroughly entertained in the process. Of course, he had a good screenplay by Ernest Lehman to work with, along with one of the greatest leading men of all time. He had a leading lady with enough skill to evoke his favorite leading lady, Grace Kelly, without embarrassing herself (as Tippi Hedren came close to doing when she tried). He had Bernard Herrmann's wonderful score, alternately pulse-pounding and romantic, and Robert Burks's cinematography. He had James Mason, Martin Landau, and Jessie Royce Landis as support. I would call it my favorite Hitchcock film, but that's maybe only because I've just seen it, and my ranking will probably change the next time I see Notorious (1946) or Rear Window (1954) again.

Thursday, February 18, 2016

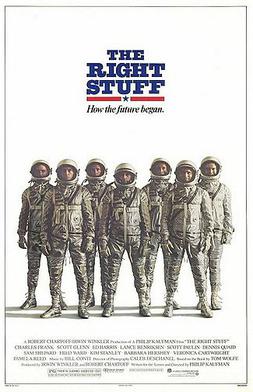

The Right Stuff (Philip Kaufman, 1983)

With its brightly irreverent tone toward subject matter that typically brought out pious patriotism in Americans, The Right Stuff feels more like a film of the 1970s than of the Reagan '80s, which may be why it was a box-office disappointment. It remains true that some of the parts of the film -- the caricatures of the German scientists, the publicists, the press, and politicians like Lyndon Johnson (Donald Moffat) -- don't fit snugly with the genuine heroism shown by the astronauts and test pilot. But that's because writer-director Philip Kaufman dared to assume a point of view on the material that was fresh and unconventional -- a rarity in American film of the '80s. Some of the tone of the film can be found in its source, Tom Wolfe's book, which was designed as a corrective to the "official story" of the Mercury 7 that was provided by Life magazine. Instead of squeaky clean superbeings devoted to wife and family, the astronauts were just human beings, frequently raunchy, irreverent, and more than a little inclined to step out of marital bounds. The film's great glory is its all-star cast (though few of the actors in it were stars before it was made), with particularly good work coming from Sam Shepard, who received a supporting actor Oscar nomination as Chuck Yeager, the test pilot that the astronauts wanted to be, even as NASA and the scientists wanted them just to be glorified lab rats, plus Scott Glenn as Alan Shepard, Ed Harris as John Glenn, Dennis Quaid as Gordon Cooper, and Fred Ward as Gus Grissom. There is similar strength in the female cast, particularly Barbara Hershey as Glennis Yeager, Veronica Cartwright as Betty Grissom, Pamela Reed as Trudy Cooper, and Mary Jo Deschanel as the publicity-shy Annie Glenn, whose embarrassment at her stammer leads to a wonderfully satisfying standoff against an increasingly irate LBJ -- a man whose whims were seldom ignored. Deschanel's husband, Caleb, is the film's cinematographer. (Yes, they are the parents of Zooey Deschanel.) The movie was nominated for eight Academy Awards and won four: for sound, film editing, sound effects editing, and Bill Conti's score.

Wednesday, February 17, 2016

Tomorrowland (Brad Bird, 2015)

A critical and commercial flop, Tomorrowland is a little too much a film for kids to satisfy sci-fi geeks, and a little too heavy on the sci-fi to hold the attention of kids. It has a few good things going for it: the presence of George Clooney and Hugh Laurie in its cast, and nice performances from two young actors, Britt Robertson as Casey and Raffey Cassidy as Athena. (It's particularly good to see a sci-fi movie for kids with girls as the protagonists.) Unfortunately, the screenplay by director Bird and Damon Lindelof, with contributions to the story from Jeff Jensen, is dauntingly overcomplicated and more than a little preachy. The premise is that somewhere after the 1964 New York World's Fair, with its glittering images of the future, our culture took a turn toward pessimism. We no longer believe that we can progress toward a more equitable society or that we can solve environmental problems with collective application of science and technology, and this pessimism creates a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy. Those of us who were old enough in 1964, after the Kennedy assassination and at the beginning of the Vietnam War, may remember the mood a little more darkly than the film posits. But even granted the premise, it seems unlikely that our contemporary malaise is going to be lightened by launching a cyberpunk spaceship designed by Gustave Eiffel, Jules Verne, Nikola Tesla, and Thomas Edison into another dimension. Keegan-Michael Key has an amusing bit as the proprietor of a sci-fi memorabilia shop who says his name is Hugo Gernsback, an in-joke for science fiction fans. (His partner, played by Kathryn Hahn, is named Ursula. As in Le Guin, perhaps?) The special effects are elaborately routine CGI stuff.

Tuesday, February 16, 2016

It Happened One Night (Frank Capra, 1934)

|

| Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert in It Happened One Night |

Monday, February 15, 2016

House of Flying Daggers (Yimou Zhang, 2004)

From the kaleidoscopic color of the Peony Palace at the beginning of the film through the final duel seen through the scrim of a blizzard, House of Flying Daggers is visually extraordinary, fully deserving of its Academy Award nomination for Xiaoding Zhao's cinematography. It tends, however, to be a collection of brilliant set pieces, including a spectacular battle in a bamboo forest, held together by what could be a conventional love triangle -- if only the stories of the three members of the triangle, Jin (Takeshi Kaneshiro), Leo (Andy Lau), and Mei (Zhang Ziyi ), weren't so extraordinarily complicated. In the story by director Zhang Yimou , Feng Li, and Bin Wang, it is 859 C.E., and the police are trying to root out the House of Flying Daggers, a group of Robin Hood-style rebels against the government of the Tang Dynasty. Police captain Leo and his subordinate, Jin, hear that an agent of the Flying Daggers is working incognito at the Peony Palace, a brothel, so they arrest Mei, a blind dancer. But neither Mei nor Leo is exactly who they appear to be, which is unfortunate for Jin, who falls in love with Mei, with fatal consequences. In the end, it's best just to sit back and admire the performances of the three actors, especially Zhang Ziyi , who is truly astonishing in both the action sequences and the dramatic scenes. In addition to Zhao's cinematography, the visual impact of the film depends largely on the work of production designer, Tingxiao Huo, art director Zhong Han, and costume designer Emi Wada. Most of the exterior scenes, with the exception of the bamboo forest, were filmed on location in the Carpathian Mountains of Ukraine.

Sunday, February 14, 2016

Of Human Bondage (John Cromwell, 1934)

Somerset Maugham's 1915 autobiographical novel Of Human Bondage is one of those books nobody seems to read anymore. It's not "literary" enough for academia and it's too old-fashioned for today's readers of popular fiction. But it was a big deal when RKO bought the screen rights intending it as a vehicle for Leslie Howard as the protagonist, Philip Carey. It was director John Cromwell who, having just seen Bette Davis in The Cabin in the Cotton (Michael Curtiz, 1932), thought the young Warner Bros. contract player might be right for the role of the cockney waitress Mildred in Of Human Bondage. (The Cabin in the Cotton is the one in which she plays a backwoods seductress who tells Richard Barthelmess's character, "I'd like to kiss you, but I just washed my hair.") Davis, who was unhappy with the way Warners was handling her career, also wanted to play Mildred, and finally wore down Jack Warner's resistance to lending her to RKO. It was the film that made her a star, though she continued to battle with Warners for as long as they held her contract. It is a sensational performance in a not-very-good movie. The infatuation of Philip with Mildred is only a small part of the novel, though it's probably the most interesting, and to emphasize it, screenwriter Lester Cohen had to jettison a great deal of plot and trim some of Philip's other relationships -- notably with the romance novelist Norah (Kay Johnson) and the young Sally Athelny (Frances Dee) -- to the point of incoherence. Nor did he really succeed in making Philip's attraction to Mildred entirely credible, considering that much of the movie deals with her coldness toward him. Howard does what he can, but it's really all Davis's show, and when she's not on screen you feel everything go slack. When Academy Awards time came around, everyone expected her much talked-about performance to land her a nomination for best actress, but she was overlooked. The outcry led the Academy to change its rules for the Oscars, allowing write-ins for the first time, but although Academy records show that Davis came in third, the award went to Claudette Colbert for It Happened One Night (Frank Capra). Next year, Davis would win the first of her two Oscars for Dangerous (Alfred E. Green), a movie that's if anything even weaker than Of Human Bondage, so the award is widely regarded as a kind of consolation prize for the previous year's oversight.

Saturday, February 13, 2016

Sunset Blvd. (Billy Wilder, 1950)

Sunset Blvd., with the abbreviation, is the "official" title because it's the only way we see it in the credits of the film: as a shot of the street name stenciled on a curb. So from the beginning we are all in the gutter, and later we are looking at the stars -- or at least one fading star, Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson). Accepting the role of Norma was a truly courageous act by Swanson: She must have known that it was the part of a lifetime, but that posterity would remember her as the campy has-been silent star, and not as the actress who had a long and distinguished career, playing both comedy and drama with equal skill, or as the spunky title character of Sadie Thompson (Raoul Walsh, 1928), which earned her her first Oscar nomination. The role of Norma Desmond might have won her an Oscar if it hadn't been for another star whose career was beginning to fade: Bette Davis, who was nominated for All About Eve (Joseph L. Mankiewicz). The conventional wisdom has it that Swanson and Davis split the votes, allowing Judy Holliday to win for Born Yesterday (George Cukor). This was also a landmark film for William Holden, who had been an unremarkable leading man until his performance as Joe Gillis established his type: the somewhat cynical, morally compromised protagonist. It would earn him an Oscar three years later for another Wilder film, Stalag 17 (1953), and would be his stock in trade through the rest of his career, in films like Picnic (Joshua Logan, 1955), The Bridge on the River Kwai (David Lean, 1957), The Wild Bunch (Sam Peckinpah, 1969), and Network (Sidney Lumet, 1976). Holden almost didn't get to play Gillis; Montgomery Clift was offered the role but backed out. One story has it that Clift thought the role, of a man out to get the money of a woman he doesn't love, was too much like one he had just played, in The Heiress (William Wyler, 1949), while others have said that he backed out because the story of a man's affair with an older woman would remind people of his own earlier affair with the singer Libby Holman, 16 years his senior. There is in fact an unfortunate whiff of disapproval in Wilder's treatment of the age difference between Norma Desmond and Joe Gillis -- Norma is said to be 50, which was Swanson's age when the film was made, while Holden, who was 32, was made up to look even younger. Wilder, it must be observed, seemed to have no problems when the age difference was reversed, as in his 1954 film Sabrina, in which a 54-year-old Humphrey Bogart romances a 25-year-old Audrey Hepburn, or the 1957 Love in the Afternoon, with 28-year-old Hepburn and 56-year-old Gary Cooper. None of this, however, seriously detracts from the fact that Sunset Blvd. remains one of the great movies, with its its superb black-and-white cinematography by John F. Seitz. It won Oscars for the mordant screenplay by Wilder, Charles Brackett, and D.M. Marshman Jr., the art direction and set decoration of Hans Dreier, John Meehan, Sam Comer, and Ray Moyer, and the score by Franz Waxman. It's also one of the few films to receive nominations in all four acting categories: In addition to Swanson and Holden, Nancy Olson and Erich von Stroheim received supporting player nominations, but none of them won.

Friday, February 12, 2016

Diabolique (Henri-Georges Clouzot, 1955)

Diabolique (or Les Diaboliques) was probably one of the first foreign language films I ever saw (although I'm sure I must have seen it in a version dubbed into English, as most U.S. releases were back then). The only thing I retained from it, I'm afraid, is the surprise ending. So I'm glad to say that it holds up after all these years, as any good thriller must even when you know its twists. I am, for the record, not one who is spoiled by "spoilers": I knew the gimmick in The Crying Game (Neil Jordan, 1992) before I saw it, and I like to think I appreciated it more because I could see how it was being set up, and I enjoyed The Sixth Sense (M. Night Shyamalan, 1999) more the second time I watched it. To my mind, any good thriller with a twist has to work independently of that twist, which Diabolique does. What it has going for it especially is Clouzot's superb control of atmosphere: sets (Léon Barsacq), music (Georges Van Parys), cinematography (Armand Thirard), and of course the performances of Véra Clouzot as Christina, Simone Signoret as Nicole, Paul Meurisse as Michel, Charles Vanel as Fichet, and a gallery of mildly grotesque supporting players, all working together to create a thoroughly sordid and unpleasant but also hypnotizing milieu. Even before the murder takes place, I was seriously creeped out by the shabby old school, its rowdy boys and ratty staff, and the sadism displayed by Michel toward his wife and mistress. That said, the story doesn't entirely hold together in any dispassionate post-viewing analysis. Without giving away any of the film's secrets, I spotted numerous loose threads. To name one, why is Christina so insistent on not divorcing Michel when she's perfectly willing to go along with a plot to murder him? We are expected to believe that she's a devout Catholic with religious scruples against divorce, but surely the church is at least as much against murdering your husband as it is against divorcing him. But I'm perfectly happy to ignore the implausible when the movie is as gripping as this one is.

Thursday, February 11, 2016

Red River (Howard Hawks, 1948)

Another essential movie. There's a post going the rounds on Facebook that asks you to name the movies you've watched more than five times that you would still watch again. I haven't responded to it because there are too many movies that fit the category for me, but this would certainly be on my list. Each time I watch Red River, I have a little different reaction to it. Sometimes, for example, I'm glad when the character of Tess Millay (Joanne Dru) shows up, because it's kind of a relief from all that male bonding of the cattle drive. But this time I found that she annoyed me. I know she's meant to be the "Hawksian woman" of the movie, the character embodied so well by Jean Arthur in Only Angels Have Wings (1939), Rosalind Russell in His Girl Friday (1940), and especially Lauren Bacall in To Have and Have Not (1944) and The Big Sleep (1946). The Hawksian woman talks back to men, asserting her place in the world they dominate. But Tess Millay just talks, and even talks about how much she talks. Moreover, she's obviously there primarily to serve as a reincarnation of Fen (Colleen Gray), the woman whom Tom Dunson (John Wayne) loved and lost when he left the wagon train at the beginning of the movie. Still, even this bit of unnecessary narrative linkage is forgivable in a movie that offers so much. There is, of course, what I think of as Wayne's best performance as Dunson -- some prefer his work in The Searchers (John Ford, 1956), which I find too artfully staged by Ford. Here he shows he can do everything from Hawks's characteristic swiftly overlapping dialogue to the paranoid trail-boss martinet to the tough guy hiding his tender side. And there's Montgomery Clift's remarkable movie debut as Matthew Garth -- Red River was filmed before The Search (Fred Zinnemann, 1948), though the latter was released first. Clift, who was stage-trained, somehow learned that movie acting is done in large part with the face, and he uses his eyes particularly expressively -- he reminds me of the great silent film actors in that regard. The scene in which Garth and Cherry Valance (John Ireland) handle each other's guns is one of the great homoerotic moments in movies, but it's prepared for by the way Clift and Ireland look at each other when they first meet. And then there's one of the great supporting casts in movies, including Walter Brennan, Noah Beery Jr., and a whole lot of cattle. (Hawks, who also produced the film, graciously gave Arthur Rosson, the second unit director in charge of the cattle drive scenes, a co-director credit.) Dimitri Tiomkin's music added immeasurably to the film, but surprisingly went unnominated by the Academy, which took notice only of Christian Nyby for editing and Borden Chase for the film's story. (It was based on his story in the Saturday Evening Post, and was turned into a screenplay by Charles Schnee -- though a lot of the dialogue is so Hawksian that I suspect the director deserved a screenplay credit, too.) Naturally, like most Hawks films, it won no Oscars.

Wednesday, February 10, 2016

For a Few Dollars More (Sergio Leone, 1965)

*Actually, he has a name in both films: In Fistful he is called "Joe," which is obviously just a generic name for an americano, while in the sequel he is known as Monco, the Italian word for "one-armed," in reference to his tendency to use his left hand while keeping his gun hand under his poncho.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)