A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Wednesday, March 8, 2017

Carol (Todd Haynes, 2015)

With her Mamie Eisenhower bangs and heart-shaped face, Rooney Mara in Carol becomes the reincarnation of such '50s icons as Audrey Hepburn, Jean Simmons, and Maggie McNamara -- particularly the McNamara of The Moon Is Blue (Otto Preminger, 1953), that once-scandalous play and movie about a young woman who defies convention by talking openly about sex while retaining her virginity. It's just coincidence that Carol is set at the end of 1952 and into 1953, the year of the release of The Moon Is Blue, but the juxtaposition of McNamara's Patty O'Neill and Mara's Therese Belivet seems to me appropriate because the 1950s have become such a touchstone for examining our attitudes toward sex. Director Todd Haynes and screenwriter Phyllis Nagy, adapting a novel by Patricia Highsmith, have done an exemplary job in Carol of not tilting the emphasis toward Grease-style caricature or Mad Men-style satire of the era, or exploiting the same-sex relationship in the film for sensationalism or statement-making. Carol is a story about people in relationships, clear-sightedly viewed in a way that Therese herself would endorse. After asking her boyfriend Richard (Jake Lacy) if he's ever been in love with a boy and receiving a shocked reply that he's only "heard of people like that," Therese replies, "I don't mean people like that. I just mean two people who fall in love with each other." It's this matter-of-factness that the film tries to maintain throughout its story of Therese and Carol (Cate Blanchett), the well-to-do wife in a failing marriage. That the film is set in the 1950s, when cracks were showing in the conventional attitudes toward both marriage and homosexuality, gives piquancy to their relationship, but it doesn't limit it. The story could be (and probably is) playing itself out today in various combinations of sexual identity. The film works in large part because of the steadiness of Haynes at the helm, with two extraordinary actresses at the center and beautiful support from Sarah Paulson as Abby, Carol's ex-lover, and Kyle Chandler (one of those largely unsung actors like the late Bill Paxton who make almost everything they appear in better) as Carol's husband, the hard-edged Harge Aird. The sonic texture of the 1950s is splendidly provided by Carter Burwell's score and a selection of classic popular music by artists like Woody Herman, Georgia Gibbs, Les Paul and Mary Ford, Perry Como, Eddie Fisher, Patti Page, Jo Stafford, and Billie Holiday.

Tuesday, March 7, 2017

Assassin(s) (Mathieu Kassovitz, 1997)

|

| Michel Serrault and Mathieu Kassovitz in Assassin(s) |

Max: Mathieu Kassovitz

Hélène: Hélène de Fougerolles

Max's Mother: Danièle Lebrun

Léa: Léa Drucker

Mehdi: Mehdi Benoufa

Mr. Vidal: Robert Gendru

Inspector: François Levantal

Director: Mathieu Kassovitz

Screenplay: Nicolas Boukhrief, Mathieu Kassovitz

Cinematography: Pierre Aïm

Production design: Philippe Chiffre

Music: Carter Burwell

Perhaps no movie since Network (Sidney Lumet, 1976) has sledgehammered television quite so thoroughly as Assassin(s). But where Network took the business of television for its target, Assassin(s) aims at the medium's ubiquity and its desensitizing effect on viewers. It's not a novel point, of course, and even the spin writer-director Mathieu Kassovitz decides to give it -- the effect TV has in creating a culture of violence -- is neither fresh nor unquestioned. The story at the film's center is about an aging professional hit man, Mr. Wagner, who takes on a young petty thief, Max, as his apprentice. It's set in the Parisian banlieus that were the socio-political milieu for Kassovitz's earlier (and much better) film about violence, La Haine (1995). It opens with Mr. Wagner guiding Max into the brutal and entirely gratuitous murder of an elderly man, and then flashes back to bring the story up to a recapitulation of the event -- rubbing our noses in it, so to speak. Max is a layabout and a screwup, but there is a core of reluctance within him that Mr. Wagner is determined to obliterate. Eventually, Max takes on his own protégé, a teenager named Mehdi, who is decidedly not reluctant to engage in a little killing, seeing it as just an extension of the video games he plays. Throughout the film, television sets are blaring game shows, commercials, sitcoms, and even nature documentaries in the background, an ironic if sometimes heavy-handed counterpoint to the murders committed by Mr. Wagner, Max, and Mehdi. Kassovitz stages much of the film well, extracting full shock value, and he sometimes embroiders the realism of the story with surreal touches: At one point, when Mr. Wagner is walking away from Max, we see a demonic tail emerge from beneath Wagner's overcoat -- or is it Max, perpetually stoned, who sees this? More effectively, reinforcing Kassovitz's treatment of the effects of television, Mehdi -- who is coming unglued after his first commissioned hit -- watches a TV sitcom about a group of young people that suddenly turns into violent, necrophiliac pornography, accompanied by a laugh track. Kassovitz showed undeniable talent with La Haine, and some of it is on display here. Assassin(s) was booed at the Cannes festival, and has never received a wide commercial release in the United States, but it's something of a fascinating (if often repellent) failure.

Monday, March 6, 2017

Stage Fright (Alfred Hitchcock, 1950)

|

| Marlene Dietrich and Jane Wyman in Stage Fright |

Charlotte Inwood: Marlene Dietrich

Ordinary Smith: Michael Wilding

Jonathan Cooper: Richard Todd

Commodore Gill: Alastair Sim

Mrs. Gill: Sybil Thorndike

Nellie Goode: Kay Walsh

Mr. Fortescue: Miles Malleson

Freddie Williams: Hector MacGregor

"Lovely Ducks": Joyce Grenfell

Inspector Byard: André Morell

Chubby Bannister: Patricia Hitchcock

Sgt. Mellish: Ballard Berkeley

Director: Alfred Hitchcock

Screenplay: Whitfield Cook, Alma Reville

Based on a novel by Selwyn Jepson

Cinematography: Wilkie Cooper

Art direction: Terence Verity

Film editing: Edward B. Jarvis

Music: Leighton Lucas

The first stage of Marlene Dietrich's Hollywood career, when she was under the tutelage of Josef von Sternberg, ended with her being labeled "poison at the box office" by a disgruntled exhibitor in 1938, a label that helped push many of her contemporaries -- Greta Garbo, Norma Shearer, Luise Rainer -- into early retirement. Dietrich was made of sterner stuff, and after a celebrated turn entertaining American troops during World War II, she carved out a second film career by taking on character roles in films by major directors like Billy Wilder in A Foreign Affair (1948) and Witness for the Prosecution (1957), Fritz Lang in Rancho Notorious (1952), Orson Welles in Touch of Evil (1958), and Alfred Hitchcock in Stage Fright. Of these, the Hitchcock film is surprisingly the least memorable. It may be that Dietrich, who had learned everything she could about lighting and camera angles from Sternberg and cinematographers like Lee Garmes, was too much the diva for Hitchcock, who liked to be in control on his sets. But the fact remains that she is probably the most interesting thing about Stage Fright, a somewhat overcomplicated and sometimes scattered mystery in which we pretty much know whodunit from the beginning. Her appearances often come as a welcome relief from the rather tepid romantic triangle involving the characters played by Jane Wyman, Richard Todd, and Michael Wilding. Dietrich sings -- if that's the right word for what she does, being more diseuse than singer -- a few songs, including "La Vie en Rose" and Cole Porter's "The Laziest Gal in Town," and wears some Christian Dior gowns as Charlotte Inwood, the star of a musical revue in London, who bumps off her husband with the help of her lover, Jonathan Cooper, who is also the lover of a young student at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, Eve Gill. But Eve also gets caught up in the murder plot when she falls for the detective investigating the case, Wilfred Smith. Also providing relief from the romantic plot are Alastair Sim and Sybil Thorndike as Eve's separated and slightly eccentric parents, and some funny cameos by Miles Malleson and Joyce Grenfell. There are some clever Hitchcockian moments, including a flashback that turns out to be a complete misdirection and some skillful tracking shots by cinematographer Wilkie Cooper. But Wyman, the only American-born member of the cast, feels out of her element, and Wilding turns his character into a moonstruck milksop. (Whatever did Elizabeth Taylor see in him?)

Sunday, March 5, 2017

Poil de Carotte (Julien Duvivier, 1932)

Poil de Carotte -- which means "carrot top" -- is a curious amalgam of fairytale themes and psychological realism. The film evokes fairytales with its story of a neglected and exploited child who has a kindly godparent, set in a picturesque French village that, except for the absence of a castle with a prince in it, could have doubled for the setting of Cinderella. We first meet the film's Cinderella analog, François Lepic (Robert Lynen), known universally as "Poil de carotte," as he is about to leave school for a vacation back home. He doesn't really want to go: When we first see him, he is being criticized by a teacher for having written in an essay, "A family is a group of people forced to live together under one roof who can't stand one another." We soon find out how he comes by this cynical definition when he arrives home to his vaguely neglectful father (Harry Baur), his icy, controlling mother (Catherine Fonteney), and his spoiled older siblings, Ernestine (Simone Aubry) and Félix (Maxime Fromiot). His status in the family becomes apparent at the dinner table, where he sits licking his lips in anticipation of the dish of melon slices being passed around, only to have his mother say he doesn't want any, apparently because she doesn't like melons. After dinner, he is sent to take the melon rinds -- he gnaws on them once he's outside -- to the rabbits and to shut the gate to the chicken yard. He protests: It's dark outside and he's scared. But his sister and brother refuse the task because they're both reading, and he's sent out into the night, which he imagines to be full of ghosts dancing in a ring. His only escape from the chores, his mother's harshness, and his father's indifference is to visit his godfather (Louis Gauthier), a cheerful idler, where he wades in the brook and has a mock wedding with a little neighbor girl, Mathilde (Colette Segall), presided over by the godfather playing a tune on his hurdy-gurdy. It's a lovely little pastoral idyll that ends all too soon. As he returns home, Poil de Carotte realizes how lonely and unloved he is, and he begins to contemplate suicide. This abrupt reversal of mood comes from an 1894 novella by Jules Renard that writer-director Julien Duvivier first adapted for a silent movie version in 1926. It's a little too abrupt for a work of psychological truth: Poil de Carotte has been seen as resilient and resourceful up to this point, and his deep depression comes upon him all too suddenly. When he finally achieves a connection with his father, in a scene that despite the dramatic flaws of the film is quite touching, it's explained to us that Poil de Carotte was conceived by accident, long after the husband and wife had ceased to love each other. He therefore became an object of resentment by both parents. At the end, the father vows that everyone will call him François, not Poil de Carotte, henceforth. The performances by Lynen and Baur make this second reversal plausible, if not entirely convincing. Duvivier's direction is more solid than his screenplay, and the film is at its best in the scenes of village life, beautifully shot by Armand Thirard.

Saturday, March 4, 2017

Hail, Caesar! (Joel Coen and Ethan Coen, 2016)

With Hail, Caesar! Joel and Ethan Coen return to Old Hollywood, the scene of one of their earliest films, the dark horror-comedy Barton Fink (1991), this time to give us what appears to be a cotton-candy fantasia on movie genres. But Hail, Caesar! seems to me the more successful film. In its sly way it reveals the grip that Hollywood myth and history have on our imaginations, using parodies of Hollywood genre films not just to send up their absurdities but also to show how deeply they color our dreams. At the same time, it explores Hollywood history -- the hold the old studios had on actors' lives, the role of publicity and gossip in creating and destroying stars, the interaction with politics during the Red Scare of the late '40s and '50s -- and combines it with the parody sequences to create a movie that turns out to be a parody of movies about The Movies, a genre that includes everything from the many versions of A Star Is Born to Singin' in the Rain (Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen, 1952) to, well, Barton Fink. The individual parodies -- the biblical epic, the drawing room drama based on a Broadway hit, the singing-cowboy Western, the Esther Williams extravaganza, the sailors-on-a-spree musical -- are all spot on. But it takes a special audacity -- something the Coens have never lacked -- to send up the anti-communist hysteria that led to the HUAC investigation and the blacklist. The Coens do it by treating the paranoid suspicion that left-wingers were undermining the American Way of Life by injecting Marxism into the movies as if it were real. So we have a communist cell made up of writers who kidnap a movie star for ransom, and another star who defects to the Soviets when the writers row him out to a submarine at night. It's a reductio ad absurdum of Cold War hysteria, as brilliantly handled by the Coens as it was by Stanley Kubrick in Dr. Strangelove (1964). The Coens also tease us by dropping the names of real people into the script. Josh Brolin plays a studio production chief and fixer named Eddie Mannix, which is the name of a real-life Hollywood fixer who kept wayward stars out of the headlines, and he reports to a studio executive in New York named Nick Schenck, the name of the president of Loew's, Inc., which owned MGM. One of the members of the communist cell in the film, a professor "down from Stanford," is called Herbert Marcuse (John Bluthal), the name of a Marxist philosopher popular with the New Left of the 1960s. It's a film of wonderful cameos, including George Clooney as the kidnapped star, Scarlett Johansson as the Esther Williams equivalent, Ralph Fiennes as the director Laurence Laurentz, and Channing Tatum emulating Gene Kelly as the singing and dancing sailor. Tilda Swinton plays the film's competing gossip columnists, Thora and Thessaly Thacker, based on the notoriously powerful Hedda Hopper and Louella Parsons. By making them twins, the Coens seem to have conflated them with the competing advice columnists Abigail Van Buren and Ann Landers, née Pauline and Esther Friedman.

Friday, March 3, 2017

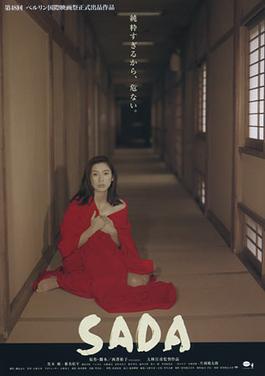

Sada (Nobuhiko Obayashi, 1998)

Having seen House (Nobuhiko Obayashi, 1977) and In the Realm of the Senses (Nagisa Oshima, 1976), I had to see what the director of the former -- a brightly colored, over-the-top horror film, set to a bubble-gum pop soundtrack, about a gaggle of Japanese schoolgirls who find themselves in a haunted house and proceed to die in various colorful and inventive ways -- would do with the latter -- a sexually explicit account, with full nudity and unsimulated copulation, of the crime of Sada Abe, who in 1936 killed her lover, Kichizo Ishido, carved their names on his body, and cut off his genitals, carrying them around with her until she was arrested. The story of Sada has been the subject of numerous books and at least five movies in Japan, after her trial -- which resulted in five years in prison -- set off a nationwide sensation, turning her into a kind of folk hero. The result is a curiously show-offy film that Obayashi fills with all manner of tricks: switches from color to black-and-white, characters breaking the fourth wall, eccentric cuts and startling shifts of tone, and deliberate violations of cinematic convention. In one scene, Sada (Hitomi Kuroki) and her lover, whose name has been changed to Tatsuzo (Tsurutaro Kataoka) in the film, are walking along the street together. The camera follows Tatsuzo from right to left as he speaks, then cuts to Sada as she replies. Film convention calls for a shot followed by a reverse shot, in which we see first Tatsuzo and then Sada from different angles. Instead, Obayashi cuts to Sada, filmed from the same angle and still traveling from right to left, as if she has somehow physically replaced Tatsuzo. This and similar impossible cuts and angles in the film are probably meant to suggest Sada's identification with her lover. Tone shifts mark the film from the beginning: It opens with 14-year-old Sada's rape by a teenage boy, a harrowing scene that is nevertheless somehow played as if it were comic, just as later Sada's work as a prostitute shifts into comic mode with speeded-up action and cuts to a voyeur watching from his hiding place, and a fight with Tatsuzo's wife becomes almost slapstick. Obayashi seems determined to avoid anything that smacks of melodrama or sentimentality. but not always successfully. The screenplay, by Yuko Nishizawa, tries to add depth to Sada's story by inventing a young medical student, Okada (Kippei Shina), who tends to her after her rape. He becomes a symbol of Sada's loss of anything but physical love when he is forced to part from her: He gives her his scalpel and has her mime cutting out his heart and taking it with her -- an obvious foreshadowing of her actual use of the scalpel on Tatsuzo. Sada spends much of the film hoping to be reunited with Okada, only to find that he has leprosy and has been sent to an island on the Inland Sea for quarantine. The film ends with a shot of an elderly woman looking out across the sea to the island. In contrast to Oshima's In the Realm of the Senses, Obayashi's film avoids nudity, but this only serves to add another layer of distance between the viewer and Sada. Kuroki, a beautiful young actress, does what she can with the role, but the constant camera tricks and the limitations imposed by the script never let us get more than a superficial glimpse of what drove Sada Abe to act as she did.

Thursday, March 2, 2017

The Killers (Robert Siodmak, 1946)

Burt Lancaster and Ava Gardner, at the start of their Hollywood careers, shine out against the noir background of The Killers like the stars they became. Which is perhaps the only major flaw in Robert Siodmak's version of -- or rather extrapolation from -- Ernest Hemingway's classic short story. They're both terrific: Lancaster underplays for once in his film career, which began with this movie, and no one was ever so beautiful or gave off such strong "bad girl" vibes as Gardner. But their presence tends to upend the film, which really stars Edmond O'Brien and a fine cast of character actors. Hemingway's story accounts for only the first 20 minutes or so of the film, the remaining hour of which was concocted by Anthony Veiller, John Huston, and Richard Brooks. In the Hemingway part of the movie, two hitmen (William Conrad and Charles McGraw) enter a small-town diner looking for their target, a washed-up boxer they call "the Swede." They bully the diner owner and tie up the cook and Nick Adams (Phil Brown), but when they decide that the Swede isn't going to show up for his usual evening meal, they leave. Nick runs to warn the Swede, Ole Anderson (Lancaster), in his rooming house, but the man exhibits only a passive acceptance of his fate. The short story ends with the Swede turning his face to the wall and Nick returning to the diner, but in the film we see the hitmen arrive at the rooming house and kill the Swede. What follows is a backstory that Hemingway never bothered with -- although he later told Huston that he liked the movie -- about an insurance investigator's probe into the killing. The Swede had left a small insurance policy, and when the investigator, Reardon (O'Brien), contacts the beneficiary he begins to find threads that lead him back to an earlier payroll heist. With the help of a friend on the police force, Lubinsky (Sam Levene), who knew the Swede from his boxing days, Reardon sorts out the tangled story of what happened to the loot and how the Swede became the target of a hit. Siodmak's steady hand as a director earned him an Oscar nomination, as did Arthur Hilton's editing and Miklós Rózsa's score, which features a four-note motif that was lifted by composer Walter Schumann for the familiar "dum-da-dum-dum" title music of the 1950s TV series Dragnet, leading to a lawsuit that was settled out of court. Veiller was also nominated for the screenplay, but the contributions of Huston and Brooks went uncredited, largely because they were under contract to other studios.

Wednesday, March 1, 2017

Three Silent Films by Ozu

|

| Yasujiro Ozu |

I Flunked, But.... (Ozu, 1930)

Tokyo Chorus (Ozu, 1931)

I think the films of Yasujiro Ozu are the perfect exemplar of that powerful task of motion pictures: to enlarge human sympathies. Ozu typically does it by working in his characteristic milieu: the family. Most of us have families, and when we don't (or when we recognize intolerable flaws in the ones we find ourselves in), we form something to substitute for them: clubs, cliques, fraternities, political parties. These three silent movies, lesser or little-known parts of Ozu's oeuvre, shine with their director's deep understanding of human connections. They also document the impact of the Great Depression, not just on Japan but on daily lives around the world. Two of them are about actual nuclear families, the other about a kind of surrogate family. They range from crime melodrama to slapstick comedy to a domestic drama threaded through with humor. All of them reveal Ozu's knowledge of American genre film as well as his ability to transform the generic into the personal.

|

| Emiko Yagumo and Tokihiko Okada in That Night's Wife |

That Night's Wife begins with a touch of gangster film as we watch the police patrolling the nighttime streets, rousting a homeless man from his perch between the towering columns of a building, then witness a daring robbery of an office by a man masked with a bandanna and the police pursuit that follows. But we gradually learn that the man (Tokihiko Okada) has committed the robbery because he has a sick child and can't pay the doctor. Most of the film takes place in his small apartment, where his wife (Emiko Yagumo) is tending to the child, who the doctor says will be all right if she survives the night. Then a detective (Togo Yamamoto), who has posed as a cab driver and brought the man home, arrives. There's a standoff between the couple and the detective in which, after trying to stay awake all night, the detective prevails. But the film ends with an unexpected turn that in other hands might come off as sheer sentimentality but in Ozu's manages to feel like the working out of an ethical dilemma.

|

| Tatsuo Saito in I Flunked, But.... |

|

| Tokihiko Okada in Tokyo Chorus |

Tuesday, February 28, 2017

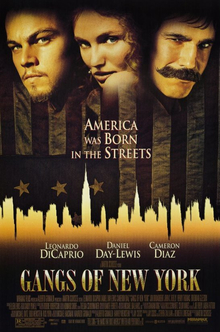

Gangs of New York (Martin Scorsese, 2002)

Gangs of New York is such a sprawling, unfocused movie that I can almost imagine the filmmakers throwing up their hands and sighing, "Well, at least we've got Daniel." Because Daniel Day-Lewis's performance as Bill "The Butcher" Cutting holds the film together whenever it tends to sink into the banality of its revenge plot or to wander off into the eddies of New York City history. A historical drama like Gangs of New York needs two things: a compelling central story and an audience that knows something about the history on which it's based. But for all their violence and their anticipation of problems that continue to manifest themselves in the United States, the Draft Riots of 1863 and the almost two decades of gang wars that led up to them are mostly textbook footnotes to most Americans. Director Martin Scorsese's determination to depict them led to the hiring of a formidable team of screenwriters -- Jay Cocks, who wrote the story, and Steven Zaillian and Kenneth Lonergan, who collaborated with Cocks on the screenplay. Unfortunately, the narrative thread that they came up with is tired. As a boy, Amsterdam Vallon saw his father, an Irish Catholic nicknamed "Priest" (Liam Neeson), cut down by Bill the Butcher in a huge battle between the Irish immigrant gang, the Dead Rabbits, and Bill's Protestant gang, the Natives. Sixteen years later Vallon (Leonardo DiCaprio) returns to the Five Points neighborhood determined to get revenge on Bill, who has managed to make peace with many of the old members of Vallon's father's gang and to become a power-player aligned with Tammany Hall and Boss Tweed (Jim Broadbent). Vallon is introduced to Bill's criminal enterprise by an old boyhood friend, Johnny (Henry Thomas), and he begins to fall under Bill's spell -- along with that of a pretty pickpocket, Jenny Everdeane (Cameron Diaz). But the relationship between Vallon and Jenny stirs the jealousy of Johnny, who is smitten with her, and he reveals to Bill that Vallon is the son of his old enemy, leading to a climactic showdown -- one that just happens to occur simultaneously with the Draft Riots. There's a lot of good stuff in Gangs of New York, including Michael Ballhaus's cinematography and Dante Ferretti's production design -- the sets were constructed at Cinecittà Studios in Rome. But the awkward attempt to merge the romantic revenge plot with the historical background shifts the focus away from what the film is supposedly about: racism, anti-immigrant nativism, political corruption, and exploitation of the poor. "You can always hire one half of the poor to kill the other half," Tweed says. Oddly (and sadly), Gangs of New York seems more relevant today than it did in 2002, when the country was recovering from the 9/11 attacks. Then, the Oscar-nominated anthem by U2, "The Hands That Built America," which concludes the film seemed to promise a spirit of unity, an affirmation that the country had overcome the antagonisms depicted in the movie. Today it has a far more ironic effect.

Monday, February 27, 2017

Y Tu Mamá También (Alfonso Cuarón, 2001)

|

| Gael García Bernal in Y Tu Mamá También |

Julio Zapata: Gael García Bernal

Tenoch Iturbide: Diego Luna

Narrator: Daniel Giménez Cacho

Silvia Allende de Iturbide: Diana Bracho

Diego "Saba" Madero: Andrés Almeida

Ana Morelos: Ana López Mercado

Manuel Huerta: Nathan Grinberg

Maria Eugenia Calles de Huerta: Verónica Langer

Cecilia Huerta: Maria Aura

Alejandro "Jano" Montes de Oca: Juan Carlos Remolina

Chuy: Silverio Palacios

Director: Alfonso Cuarón

Screenplay: Carlos Cuarón, Alfonso Cuarón

Cinematography: Emmanuel Lubezki

Production design: Marc Bedia, Miguel Ángel Álvarez

Film editing: Alfonso Cuarón, Alex Rodríguez

Alfonso Cuarón's Y Tu Mamá También is kept aloft for so long by wit and energy, and by the skills of its actors, director, and cinematographer, that it's a disappointment to consider the way it deflates a little at the end. It is, on the whole, a brilliant transfiguration of several well-worn genres: the teen sex comedy, the road movie, the coming-of-age fable. Cuarón has credited Jean-Luc Godard's Masculin Féminin (1966) as a major inspiration, but I think it owes as much to François Truffaut's Jules and Jim (1962), not least in Daniel Giménez Cacho's superbly ironic voiceover narrator, who provides a larger context for the actions of the three main characters. It's the narrator, for instance, who tells us that the traffic jam that holds up our middle-class teenagers was caused by the death of a working man who tried to cross the freeway because otherwise he would have had to walk a mile and a half out of his way to use the only crossing bridge. Or that Chuy, the fisherman who befriends the trio when they finally reach the secluded beach, will lose his livelihood to developers and commercial fisheries and wind up as a janitor in an Acapulco hotel. Somehow, Cuarón manages to avoid heavy-handedness with these comments, injecting the necessary amount of serious social commentary into a story about two horny Mexico City teenagers and the older woman who goes in search of a beach called "Heaven's Mouth" with them. Even in the story, the subtext of social class in contemporary Mexico keeps peeking through: There's a slight tension between the upper-middle-class Tenoch, whose father is a government official, and the lower-middle-class Julio that's suggestive of Tenoch's sense of privilege. Similarly, Luisa, who was trained as a dental technician, confesses to a sense of inferiority to her husband, Jano, Tenoch's cousin, and his better-educated friends. The screenplay by Cuarón and his brother, Carlos, deserved the Oscar nomination it received for these attempts to provide a deep backstory for the characters. Even so, the film owes much to the obvious rapport between Luna and García Bernal, and to the steady centering influence of Verdú, all of whom participated in rehearsals that were often improvisatory embroidering on the Cuaróns's screenplay. Cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, who would go on to receive three consecutive Oscars for much showier work on Cuarón's Gravity (2013) and on Alejandro Iñárritu's Birdman (2104) and The Revenant (2015), here maintains a strictly documentary style of camerawork, though often with the subtle use of long takes and wide-angle lenses. As I said, I think the film deflates a bit at the end with the revelation of Luisa's death: It seems an unnecessary attempt to moralize, to provide a motive -- knowing that she has terminal cancer -- for her running away and having sex with the boys, turning it into only a final fling. Would we think less of Luisa if she were simply asserting her right to be as pleasure-driven as her philandering husband? Were the Cuaróns attempting to obviate slut-shaming by giving Luisa cancer? I hope not, because the film shows such intelligence and sensitivity otherwise.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)