A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Sunday, March 12, 2017

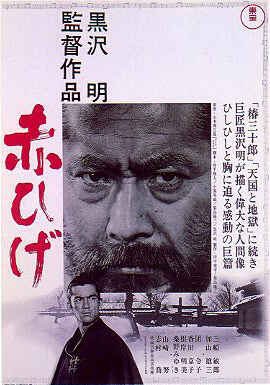

Red Beard (Akira Kurosawa, 1965)

The influence of American movies on the work of Akira Kurosawa is well-known. His viewings of American Westerns, for example, helped shape such classics as Seven Samurai (1954) and Yojimbo (1961). But Red Beard seems to me an instance in which the influence wasn't so fortunate. It's a kind of reworking of MGM's series of Dr. Kildare movies of the 1930s and '40s, in which the ambitious young intern Dr. Kildare tangles with the crusty older physician Dr. Gillespie and thereby learns a few lessons -- a dynamic that persists today in TV series like Grey's Anatomy and soap operas like General Hospital. In Red Beard, ambitious young Dr. Noboru Yasumoto (Yuzo Kayama) is sent to work under crusty older Dr. Kyojo Niide (Toshiro Mifune), known as "Red Beard" for an obvious facial feature. It's the 19th century, the last years of the Tokugawa shogunate, and Yasumoto, having finished his studies in Nagasaki, expects that the influence of his father, a prominent physician, will land him a role as the shogun's personal physician. He's angry when he finds that he's been sent to a rural clinic that mainly serves the poor. There is one affluent patient at the clinic, however: a young woman known as "The Mantis" (Kyoko Kagawa) because she stabbed two of her lovers to death. Her wealthy father has built a house for her on the grounds of the clinic, but only Red Beard is allowed to approach and treat her. Yasumoto initially rebels against the assignment, feeling disgust for the patients: When he asks the physician he's replacing at the clinic what smells like "rotten fruit," he's told that that's the way the poor smell. But eventually (and predictably), he learns to respect the work of Red Beard and to value the lives of his patients. Red Beard is hardly a bad movie: Kurosawa brilliantly stages the first encounter of Yasumoto and The Mantis, who has escaped from her house, in a carefully framed sequence, a long take in which the doctor and the madwoman begin at opposite sides of the wide screen -- it's filmed in Tohoscope, an anamorphic process akin to Cinemascope -- with a tall candlestick between them. Gradually, accompanied by slow camera movements, the two approach each other, the doctor trying to gauge the motives and the sanity of the young woman. Finally the calm framing of the scene is shattered into a series of quick cuts, as she attacks with a pair of scissors, and the scene ends with a brief shot of Red Beard suddenly opening the door. Red Beard was shot by two acclaimed cinematographers, Asakazu Nakai and Takao Saito, both of whom frequently worked with Kurosawa, and the production design was by Yoshiro Muraki, who fulfilled Kurosawa's exacting demands for meticulous faithfulness to the period, including the construction of what was virtually a small village, using only materials that would have been available in the period. But what keeps Red Beard from the first rank of Kurosawa's films, I think, is the sentimental moralizing, the insistence of having the characters "learn lessons." Yasumoto, having learned his initial lesson about valuing the lives of the poor, is given a young patient, Otoyo (Terumi Niki), rescued from a brothel where she has essentially gone feral. (During the rescue scene, Kurosawa can't resist having his longtime star Mifune show off some of his old chops: The doctor takes on a gang of thugs outside the brothel and single-handedly leaves them with broken arms, legs, and heads. It's a fun scene, but not particularly integral to the character.) When Yasumoto has succeeded in teaching Otoyo to respond to kindness, it then becomes her turn to teach others what she has learned. The moralizing overwhelms the film, leaving us longing for the deeper insight into the characters found in films by Kurosawa's great contemporaries Yasujiro Ozu and Kenji Mizoguchi.

Saturday, March 11, 2017

Moonlight Serenade (Masahiro Shinoda, 1997)

Moonlight Serenade is an entertaining mélange of several genres: historical drama, coming-of-age tale, and family drama, with a touch of road movie and two romantic subplots, all kept more or less in focus by a framing story that turns it into a film about the endurance of the Japanese people in the face of everything that life can throw at them. It begins with Keita Onda (Kyozo Nagatsuka), a man in his 60s, watching the news reports about the 1995 earthquake that devastated Kobe. The film flashes back to 10-year-old Keita (Hideyuki Kasahara) watching, from a safe distance, the red sky over a burning Kobe after an American air raid. Like the other boys watching the fiery sky, who claim that the sight gives them an erection, Keita is more excited than frightened. Then the war ends, and Keita's family is marshaled his father, Koichi (also played by Nagatsuka), into a difficult journey from Awaji, where they now live, to the ancestral home in Kyushu. Keita is entrusted with seeing after the box that supposedly contains the ashes of his elder brother, who enlisted in the Japanese navy at 17 and was killed two years later when his ship hit a mine. (What the box actually contains is one of the film's surprises.) The family also consists of Koichi's wife, Fuji (Shima Iwashita), and their 18-year-old son, Koji (Jun Toba), and small daughter, Hideko (Sayuri Kawauchi). The neighbors are astonished that anyone should be making such a perilous trip across American-occupied Japan; the trains are unreliable and overcrowded and ships are still prey to undetonated mines. Gossip builds that Koichi, a tough police officer and a notoriously hidebound traditionalist, intends for his family to commit ritual suicide when they reach the ancestral burial place. The journey is in fact difficult and often suspenseful, but director Masahiro Shinoda, working from a screenplay by Katsuo Naruse from a novel by Yu Aku, maintains a light touch, infusing the difficult journey with humor. The film develops a love interest for Koji in the form of Yukiko (Hinano Yoshikawa), an orphaned girl who is also going to Kyushu, to live with relatives she has never seen. Koji, who hates his father, plans to run away somewhere along the journey, and when he meets Yukiko, he tries to persuade her to join him. A group of secondary characters joins the family on shipboard, including a black marketer (Junji Takada), whose stash of whiskey helps break down Koichi's stiff reserve (along with his policeman's distaste for the black market), and a traveling film exhibitor whose collection of movies includes some illicit samurai films that have been banned by the occupying Americans for their militarism. Keita, naturally, is enchanted by the movies, and there's a charming scene late in the film in which he goes to a theater to see Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1942) with his father. Unfortunately, Keita can't follow the American romance -- some of the words in the Japanese subtitles are too hard for him, he says -- and his father only says he'll have to be older to understand it. Moonlight Serenade is one of the late films by Shinoda, who apprenticed with Yasujiro Ozu and became a prominent member of the "Japanese New Wave" in the 1960s. It displays his skill at storytelling, handling several subplots and surprises, and has a fine sympathetic treatment of the people caught up in the postwar crisis. But it's a bit old-fashioned for a movie made in the 1990s, too overloaded with characters and incidents for its own good, and the frame story seems unnecessary.

Friday, March 10, 2017

The Ladykillers (Alexander Mackendrick, 1955)

The British used to like to think of themselves as congenitally disposed to law and order -- so much so that they didn't need a written constitution to maintain it. Crime, when it happened, was presumed to follow rules of decorum, or at least that's the case in countless "cozy" murder mysteries like Agatha Christie's Miss Marple series. The trend reached its peak in the Ealing Studios comedies featuring Alec Guinness in the 1950s: Kind Hearts and Coronets (Robert Hamer, 1949), The Lavender Hill Mob (Charles Crichton, 1951), and The Ladykillers. Murder and larceny are treated almost as genteel, if eccentric, pursuits, avoiding violence unless it becomes unpleasantly necessary. It's significant that the most menacingly violent member of the crew that pulls off the robbery in The Ladykillers speaks with a foreign accent and is played by the Czech-born actor Herbert Lom, as if only a foreigner would think of killing the sweet old lady (Katie Johnson) who threatens to reveal their crime to the police. It's possible, too, that the mastermind of the crew, Prof. Marcus (Guinness), is not entirely British -- his surname has foreign overtones -- although the oversize false teeth Guinness wears do seem like the product of British dentistry. The Ladykillers is a wry tribute to the Britain that had just muddled through World War II and was emerging from postwar austerity. The house in which Mrs. Wilberforce lives, perched precariously on the brink of a railway tunnel, has had its upper stories condemned as unsafe after the wartime bombing, but it's filled with tributes to the Empire that was crumbling as steadily as the house. She lives alone, guarded only by her late husband's parrots, which he had rescued from the ship he went down on, and by the local constabulary, who tolerate her frequent visits to the station to report things like a neighbor's sighting of a flying saucer. She is obviously an easy mark, however, for Prof. Marcus and his gang: Claude (Cecil Parker), Louis (Lom), Harry (Peter Sellers), and the punchy ex-boxer One-Round (Danny Green), who pose as a string quintet practicing in the rooms Marcus leases in her house. (They play a recording of a Boccherini minuet while they plot the heist, and afterward stash the loot in their instrument cases.) Naturally, they bumble themselves into revealing their secret to Mrs. Wilberforce, and after deciding that they must kill her to protect themselves manage to bumble themselves into killing one another instead. As usual with Ealing Studios comedies, the acting is uniformly delightful: Guinness said he modeled his character on Alastair Sim, for whom the role was originally intended, and it's fun to see Sellers and Lom together some years before their re-teaming in the Pink Panther films. Interestingly, this tribute to the Brits was written by an American, William Rose, who received an Oscar nomination for his screenplay. Rose had stayed on in England and married an Englishwoman after service in World War II. Otto Heller's color cinematography and Jim Morahan's art direction add greatly to the success of the film.

Thursday, March 9, 2017

Every-Night Dreams (Mikio Naruse, 1933)

|

| Tatsuo Saito and Sumiko Kurishima in Every-Night Dreams |

Wednesday, March 8, 2017

Carol (Todd Haynes, 2015)

With her Mamie Eisenhower bangs and heart-shaped face, Rooney Mara in Carol becomes the reincarnation of such '50s icons as Audrey Hepburn, Jean Simmons, and Maggie McNamara -- particularly the McNamara of The Moon Is Blue (Otto Preminger, 1953), that once-scandalous play and movie about a young woman who defies convention by talking openly about sex while retaining her virginity. It's just coincidence that Carol is set at the end of 1952 and into 1953, the year of the release of The Moon Is Blue, but the juxtaposition of McNamara's Patty O'Neill and Mara's Therese Belivet seems to me appropriate because the 1950s have become such a touchstone for examining our attitudes toward sex. Director Todd Haynes and screenwriter Phyllis Nagy, adapting a novel by Patricia Highsmith, have done an exemplary job in Carol of not tilting the emphasis toward Grease-style caricature or Mad Men-style satire of the era, or exploiting the same-sex relationship in the film for sensationalism or statement-making. Carol is a story about people in relationships, clear-sightedly viewed in a way that Therese herself would endorse. After asking her boyfriend Richard (Jake Lacy) if he's ever been in love with a boy and receiving a shocked reply that he's only "heard of people like that," Therese replies, "I don't mean people like that. I just mean two people who fall in love with each other." It's this matter-of-factness that the film tries to maintain throughout its story of Therese and Carol (Cate Blanchett), the well-to-do wife in a failing marriage. That the film is set in the 1950s, when cracks were showing in the conventional attitudes toward both marriage and homosexuality, gives piquancy to their relationship, but it doesn't limit it. The story could be (and probably is) playing itself out today in various combinations of sexual identity. The film works in large part because of the steadiness of Haynes at the helm, with two extraordinary actresses at the center and beautiful support from Sarah Paulson as Abby, Carol's ex-lover, and Kyle Chandler (one of those largely unsung actors like the late Bill Paxton who make almost everything they appear in better) as Carol's husband, the hard-edged Harge Aird. The sonic texture of the 1950s is splendidly provided by Carter Burwell's score and a selection of classic popular music by artists like Woody Herman, Georgia Gibbs, Les Paul and Mary Ford, Perry Como, Eddie Fisher, Patti Page, Jo Stafford, and Billie Holiday.

Tuesday, March 7, 2017

Assassin(s) (Mathieu Kassovitz, 1997)

|

| Michel Serrault and Mathieu Kassovitz in Assassin(s) |

Max: Mathieu Kassovitz

Hélène: Hélène de Fougerolles

Max's Mother: Danièle Lebrun

Léa: Léa Drucker

Mehdi: Mehdi Benoufa

Mr. Vidal: Robert Gendru

Inspector: François Levantal

Director: Mathieu Kassovitz

Screenplay: Nicolas Boukhrief, Mathieu Kassovitz

Cinematography: Pierre Aïm

Production design: Philippe Chiffre

Music: Carter Burwell

Perhaps no movie since Network (Sidney Lumet, 1976) has sledgehammered television quite so thoroughly as Assassin(s). But where Network took the business of television for its target, Assassin(s) aims at the medium's ubiquity and its desensitizing effect on viewers. It's not a novel point, of course, and even the spin writer-director Mathieu Kassovitz decides to give it -- the effect TV has in creating a culture of violence -- is neither fresh nor unquestioned. The story at the film's center is about an aging professional hit man, Mr. Wagner, who takes on a young petty thief, Max, as his apprentice. It's set in the Parisian banlieus that were the socio-political milieu for Kassovitz's earlier (and much better) film about violence, La Haine (1995). It opens with Mr. Wagner guiding Max into the brutal and entirely gratuitous murder of an elderly man, and then flashes back to bring the story up to a recapitulation of the event -- rubbing our noses in it, so to speak. Max is a layabout and a screwup, but there is a core of reluctance within him that Mr. Wagner is determined to obliterate. Eventually, Max takes on his own protégé, a teenager named Mehdi, who is decidedly not reluctant to engage in a little killing, seeing it as just an extension of the video games he plays. Throughout the film, television sets are blaring game shows, commercials, sitcoms, and even nature documentaries in the background, an ironic if sometimes heavy-handed counterpoint to the murders committed by Mr. Wagner, Max, and Mehdi. Kassovitz stages much of the film well, extracting full shock value, and he sometimes embroiders the realism of the story with surreal touches: At one point, when Mr. Wagner is walking away from Max, we see a demonic tail emerge from beneath Wagner's overcoat -- or is it Max, perpetually stoned, who sees this? More effectively, reinforcing Kassovitz's treatment of the effects of television, Mehdi -- who is coming unglued after his first commissioned hit -- watches a TV sitcom about a group of young people that suddenly turns into violent, necrophiliac pornography, accompanied by a laugh track. Kassovitz showed undeniable talent with La Haine, and some of it is on display here. Assassin(s) was booed at the Cannes festival, and has never received a wide commercial release in the United States, but it's something of a fascinating (if often repellent) failure.

Monday, March 6, 2017

Stage Fright (Alfred Hitchcock, 1950)

|

| Marlene Dietrich and Jane Wyman in Stage Fright |

Charlotte Inwood: Marlene Dietrich

Ordinary Smith: Michael Wilding

Jonathan Cooper: Richard Todd

Commodore Gill: Alastair Sim

Mrs. Gill: Sybil Thorndike

Nellie Goode: Kay Walsh

Mr. Fortescue: Miles Malleson

Freddie Williams: Hector MacGregor

"Lovely Ducks": Joyce Grenfell

Inspector Byard: André Morell

Chubby Bannister: Patricia Hitchcock

Sgt. Mellish: Ballard Berkeley

Director: Alfred Hitchcock

Screenplay: Whitfield Cook, Alma Reville

Based on a novel by Selwyn Jepson

Cinematography: Wilkie Cooper

Art direction: Terence Verity

Film editing: Edward B. Jarvis

Music: Leighton Lucas

The first stage of Marlene Dietrich's Hollywood career, when she was under the tutelage of Josef von Sternberg, ended with her being labeled "poison at the box office" by a disgruntled exhibitor in 1938, a label that helped push many of her contemporaries -- Greta Garbo, Norma Shearer, Luise Rainer -- into early retirement. Dietrich was made of sterner stuff, and after a celebrated turn entertaining American troops during World War II, she carved out a second film career by taking on character roles in films by major directors like Billy Wilder in A Foreign Affair (1948) and Witness for the Prosecution (1957), Fritz Lang in Rancho Notorious (1952), Orson Welles in Touch of Evil (1958), and Alfred Hitchcock in Stage Fright. Of these, the Hitchcock film is surprisingly the least memorable. It may be that Dietrich, who had learned everything she could about lighting and camera angles from Sternberg and cinematographers like Lee Garmes, was too much the diva for Hitchcock, who liked to be in control on his sets. But the fact remains that she is probably the most interesting thing about Stage Fright, a somewhat overcomplicated and sometimes scattered mystery in which we pretty much know whodunit from the beginning. Her appearances often come as a welcome relief from the rather tepid romantic triangle involving the characters played by Jane Wyman, Richard Todd, and Michael Wilding. Dietrich sings -- if that's the right word for what she does, being more diseuse than singer -- a few songs, including "La Vie en Rose" and Cole Porter's "The Laziest Gal in Town," and wears some Christian Dior gowns as Charlotte Inwood, the star of a musical revue in London, who bumps off her husband with the help of her lover, Jonathan Cooper, who is also the lover of a young student at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, Eve Gill. But Eve also gets caught up in the murder plot when she falls for the detective investigating the case, Wilfred Smith. Also providing relief from the romantic plot are Alastair Sim and Sybil Thorndike as Eve's separated and slightly eccentric parents, and some funny cameos by Miles Malleson and Joyce Grenfell. There are some clever Hitchcockian moments, including a flashback that turns out to be a complete misdirection and some skillful tracking shots by cinematographer Wilkie Cooper. But Wyman, the only American-born member of the cast, feels out of her element, and Wilding turns his character into a moonstruck milksop. (Whatever did Elizabeth Taylor see in him?)

Sunday, March 5, 2017

Poil de Carotte (Julien Duvivier, 1932)

Poil de Carotte -- which means "carrot top" -- is a curious amalgam of fairytale themes and psychological realism. The film evokes fairytales with its story of a neglected and exploited child who has a kindly godparent, set in a picturesque French village that, except for the absence of a castle with a prince in it, could have doubled for the setting of Cinderella. We first meet the film's Cinderella analog, François Lepic (Robert Lynen), known universally as "Poil de carotte," as he is about to leave school for a vacation back home. He doesn't really want to go: When we first see him, he is being criticized by a teacher for having written in an essay, "A family is a group of people forced to live together under one roof who can't stand one another." We soon find out how he comes by this cynical definition when he arrives home to his vaguely neglectful father (Harry Baur), his icy, controlling mother (Catherine Fonteney), and his spoiled older siblings, Ernestine (Simone Aubry) and Félix (Maxime Fromiot). His status in the family becomes apparent at the dinner table, where he sits licking his lips in anticipation of the dish of melon slices being passed around, only to have his mother say he doesn't want any, apparently because she doesn't like melons. After dinner, he is sent to take the melon rinds -- he gnaws on them once he's outside -- to the rabbits and to shut the gate to the chicken yard. He protests: It's dark outside and he's scared. But his sister and brother refuse the task because they're both reading, and he's sent out into the night, which he imagines to be full of ghosts dancing in a ring. His only escape from the chores, his mother's harshness, and his father's indifference is to visit his godfather (Louis Gauthier), a cheerful idler, where he wades in the brook and has a mock wedding with a little neighbor girl, Mathilde (Colette Segall), presided over by the godfather playing a tune on his hurdy-gurdy. It's a lovely little pastoral idyll that ends all too soon. As he returns home, Poil de Carotte realizes how lonely and unloved he is, and he begins to contemplate suicide. This abrupt reversal of mood comes from an 1894 novella by Jules Renard that writer-director Julien Duvivier first adapted for a silent movie version in 1926. It's a little too abrupt for a work of psychological truth: Poil de Carotte has been seen as resilient and resourceful up to this point, and his deep depression comes upon him all too suddenly. When he finally achieves a connection with his father, in a scene that despite the dramatic flaws of the film is quite touching, it's explained to us that Poil de Carotte was conceived by accident, long after the husband and wife had ceased to love each other. He therefore became an object of resentment by both parents. At the end, the father vows that everyone will call him François, not Poil de Carotte, henceforth. The performances by Lynen and Baur make this second reversal plausible, if not entirely convincing. Duvivier's direction is more solid than his screenplay, and the film is at its best in the scenes of village life, beautifully shot by Armand Thirard.

Saturday, March 4, 2017

Hail, Caesar! (Joel Coen and Ethan Coen, 2016)

With Hail, Caesar! Joel and Ethan Coen return to Old Hollywood, the scene of one of their earliest films, the dark horror-comedy Barton Fink (1991), this time to give us what appears to be a cotton-candy fantasia on movie genres. But Hail, Caesar! seems to me the more successful film. In its sly way it reveals the grip that Hollywood myth and history have on our imaginations, using parodies of Hollywood genre films not just to send up their absurdities but also to show how deeply they color our dreams. At the same time, it explores Hollywood history -- the hold the old studios had on actors' lives, the role of publicity and gossip in creating and destroying stars, the interaction with politics during the Red Scare of the late '40s and '50s -- and combines it with the parody sequences to create a movie that turns out to be a parody of movies about The Movies, a genre that includes everything from the many versions of A Star Is Born to Singin' in the Rain (Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen, 1952) to, well, Barton Fink. The individual parodies -- the biblical epic, the drawing room drama based on a Broadway hit, the singing-cowboy Western, the Esther Williams extravaganza, the sailors-on-a-spree musical -- are all spot on. But it takes a special audacity -- something the Coens have never lacked -- to send up the anti-communist hysteria that led to the HUAC investigation and the blacklist. The Coens do it by treating the paranoid suspicion that left-wingers were undermining the American Way of Life by injecting Marxism into the movies as if it were real. So we have a communist cell made up of writers who kidnap a movie star for ransom, and another star who defects to the Soviets when the writers row him out to a submarine at night. It's a reductio ad absurdum of Cold War hysteria, as brilliantly handled by the Coens as it was by Stanley Kubrick in Dr. Strangelove (1964). The Coens also tease us by dropping the names of real people into the script. Josh Brolin plays a studio production chief and fixer named Eddie Mannix, which is the name of a real-life Hollywood fixer who kept wayward stars out of the headlines, and he reports to a studio executive in New York named Nick Schenck, the name of the president of Loew's, Inc., which owned MGM. One of the members of the communist cell in the film, a professor "down from Stanford," is called Herbert Marcuse (John Bluthal), the name of a Marxist philosopher popular with the New Left of the 1960s. It's a film of wonderful cameos, including George Clooney as the kidnapped star, Scarlett Johansson as the Esther Williams equivalent, Ralph Fiennes as the director Laurence Laurentz, and Channing Tatum emulating Gene Kelly as the singing and dancing sailor. Tilda Swinton plays the film's competing gossip columnists, Thora and Thessaly Thacker, based on the notoriously powerful Hedda Hopper and Louella Parsons. By making them twins, the Coens seem to have conflated them with the competing advice columnists Abigail Van Buren and Ann Landers, née Pauline and Esther Friedman.

Friday, March 3, 2017

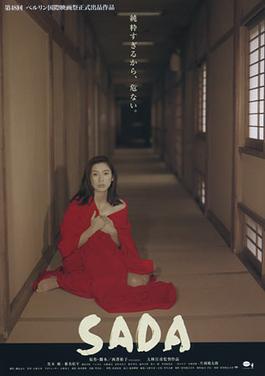

Sada (Nobuhiko Obayashi, 1998)

Having seen House (Nobuhiko Obayashi, 1977) and In the Realm of the Senses (Nagisa Oshima, 1976), I had to see what the director of the former -- a brightly colored, over-the-top horror film, set to a bubble-gum pop soundtrack, about a gaggle of Japanese schoolgirls who find themselves in a haunted house and proceed to die in various colorful and inventive ways -- would do with the latter -- a sexually explicit account, with full nudity and unsimulated copulation, of the crime of Sada Abe, who in 1936 killed her lover, Kichizo Ishido, carved their names on his body, and cut off his genitals, carrying them around with her until she was arrested. The story of Sada has been the subject of numerous books and at least five movies in Japan, after her trial -- which resulted in five years in prison -- set off a nationwide sensation, turning her into a kind of folk hero. The result is a curiously show-offy film that Obayashi fills with all manner of tricks: switches from color to black-and-white, characters breaking the fourth wall, eccentric cuts and startling shifts of tone, and deliberate violations of cinematic convention. In one scene, Sada (Hitomi Kuroki) and her lover, whose name has been changed to Tatsuzo (Tsurutaro Kataoka) in the film, are walking along the street together. The camera follows Tatsuzo from right to left as he speaks, then cuts to Sada as she replies. Film convention calls for a shot followed by a reverse shot, in which we see first Tatsuzo and then Sada from different angles. Instead, Obayashi cuts to Sada, filmed from the same angle and still traveling from right to left, as if she has somehow physically replaced Tatsuzo. This and similar impossible cuts and angles in the film are probably meant to suggest Sada's identification with her lover. Tone shifts mark the film from the beginning: It opens with 14-year-old Sada's rape by a teenage boy, a harrowing scene that is nevertheless somehow played as if it were comic, just as later Sada's work as a prostitute shifts into comic mode with speeded-up action and cuts to a voyeur watching from his hiding place, and a fight with Tatsuzo's wife becomes almost slapstick. Obayashi seems determined to avoid anything that smacks of melodrama or sentimentality. but not always successfully. The screenplay, by Yuko Nishizawa, tries to add depth to Sada's story by inventing a young medical student, Okada (Kippei Shina), who tends to her after her rape. He becomes a symbol of Sada's loss of anything but physical love when he is forced to part from her: He gives her his scalpel and has her mime cutting out his heart and taking it with her -- an obvious foreshadowing of her actual use of the scalpel on Tatsuzo. Sada spends much of the film hoping to be reunited with Okada, only to find that he has leprosy and has been sent to an island on the Inland Sea for quarantine. The film ends with a shot of an elderly woman looking out across the sea to the island. In contrast to Oshima's In the Realm of the Senses, Obayashi's film avoids nudity, but this only serves to add another layer of distance between the viewer and Sada. Kuroki, a beautiful young actress, does what she can with the role, but the constant camera tricks and the limitations imposed by the script never let us get more than a superficial glimpse of what drove Sada Abe to act as she did.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)