A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Friday, March 17, 2017

Osaka Elegy (Kenji Mizoguchi, 1936)

It's easy to imagine Kenji Mizoguchi's Osaka Elegy remade into a 1930s "women's picture" starring Bette Davis, except that nothing made in Hollywood under the infantilizing Production Code would have had the depth and insight into the real problems of women that Mizoguchi's film does. Mizoguchi's direction frames the story elegantly: He begins with a shot of the neon-lighted city, backed by the pop standard "Stairway to the Stars" on the soundtrack, as day gradually breaks and the glamour of the neon fades into the drab reality of the daytime city. We go to the home of Sonosuke Asai (Benkei Shiganoya), the head of a large pharmaceuticals company, where he berates the maids for small infractions and quarrels with his shrewish wife, Sumiko (Yoko Umemura). The opening sets a tone of disillusionment that pervades the entire film, which becomes a sharp commentary on both traditional and contemporary sexual roles. The film's protagonist is Ayako (Isuzu Yamada), switchboard operator at Asai Pharmaceuticals, whom Asai wants to become his mistress. Ayako is reluctant -- she has a boyfriend, Nishimura (Kensaku Hara), another employee at the company -- but her feckless father (Shinpachiro Asaka) has been skimming from the till at work and has lost the money in the stock market. So she quits her job, lets Asai set her up in a fancy modern apartment, and sends her father the money he needs. After Asai's wife uncovers the arrangement, a friend of Asai's, Fujino (Eitaro Shindo), tries to move in on Ayako. But Ayako reconnects with Nishimura, who proposes to her. Uncertain how he will respond to the truth about her life -- she has told him she works in a beauty parlor -- she postpones her answer. Then she learns from her younger sister that their brother is being forced to drop out of the university because her father can't pay the tuition. She gets the money by pretending to yield to Fujino's advances, but runs to Nishimura and agrees to marry him, while also confessing her liaison with Asai. As Nishimura is pondering this information, a furious Fujino arrives and after being turned away, calls the police, charging her with theft. Nishimura cravenly tells the police that he was innocently dragged into the affair by Ayako, but because it's her first offense she is released into her father's custody. Her family, whose money problems she has dutifully solved, shuns her and her brother calls her a "delinquent." Ayako walks out into the night and we follow her to a bridge, where she looks down into the trash-filled waters. But as we wonder if she is going to commit suicide, the family doctor, who has been present at several of the crisis points in her story, happens to meet her on the bridge. She asks him if there is a cure for delinquency, and when he says no, she accepts the judgment and, holding her head high, walks away toward the camera. Yamada's terrific performance was one of several she gave for Mizoguchi, establishing her as a specialist in strong female roles -- she is perhaps best-known by Western audiences as the Lady Macbeth equivalent in Akira Kurosawa's Throne of Blood (1957).

Thursday, March 16, 2017

28 Days Later (Danny Boyle, 2002)

|

| Cillian Murphy in 28 Days Later |

Selena: Naomie Harris

Frank: Brendan Gleeson

Major Henry West: Christopher Eccleston

Hannah: Megan Burns

Mark: Noah Huntley

Sgt. Farrell: Stuart McQuarrie

Corporal Mitchell: Ricci Harnett

Director: Danny Boyle

Screenplay: Alex Garland

Cinematography: Anthony Dod Mantle

Production design: Mark Tildesley

Danny Boyle's science fiction/horror film 28 Days Later was a critical and commercial success, which owes much, I suspect, to its post-apocalyptic theme, capturing a mood prevalent after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. Many viewers noted the similarity of the kiosk in the film, covered with notices posted by people searching for lost friends and relatives, to the real ones posted in New York City after the fall of the World Trade Center towers -- a prescient touch on the part of the filmmakers, since the scene was shot before the terrorist attack and its aftermath. It has also been an influential film, helping spark an interest in "zombie"* movies and TV shows. After a prologue that shows how animal-rights activists attacked a research laboratory and unwittingly released a virus that causes uncontrollable rage in its victims and is spread by contact with blood and saliva, the film's protagonist, Jim, wakes up from a coma in a London hospital to discover that he has been abandoned there and that the streets outside are empty. (The premise of someone waking up from a coma to discover a world depopulated by an incurable virus was repeated by the creators of The Walking Dead, first for the graphic novel published in 2003 and later for the TV series that began in 2010.) Jim soon discovers that he is not entirely alone: He is attacked by people infected with the virus and rescued by two who weren't: Selena and Mark. Unfortunately, Mark gets bitten by one of the infected and has to be killed, allowing Selena to explain that the disease takes hold swiftly and is incurable. Selena and Jim then discover two more survivors, Frank and his daughter, Hannah, who have a crank-operated radio that has picked up a signal from survivors north of Manchester calling for others to join them. Frank is infected and killed during their perilous drive northward, and Jim, Selena, and Hannah discover that the survivors are in a well-armed military outpost under the command of Maj. Henry West. It turns out that West has been sending out the signals especially to attract women to service his sex-starved troops, which means not only that Selena and Hannah are in danger of rape but also that Jim is expendable. Before he helps Selena and Hannah escape, Jim also hears the theory of a soldier opposed to West that the virus has not in fact spread worldwide: that it has been contained in other countries and that the island of Britain is quarantined -- a theory that Jim confirms for himself when he sees the contrails of a jet plane flying high overhead. The released film ends happily -- or at least hopefully -- when Jim, Selena, and Hannah, having escaped, construct a giant "HELLO" sign that is spotted by a plane flying reconnaissance over the cottage where they live. It's not the preferred ending of director Boyle and screenwriter Alex Garland, who proposed a bleaker resolution of the story that failed with test audiences. Well-directed and -acted, 28 Days Later does what it's designed to do: build suspense and provide interesting characters. It also resonates nicely with our paranoia about pandemic infections in the age of HIV, Ebola, and the annual influenza scare. But it doesn't hold up well under the old test of Questions You're Not Supposed to Ask: like, why has Jim been abandoned, stark naked and comatose, in a hospital? If the hospital was attacked by the infected, why wasn't he attacked? If it was evacuated -- we see a newspaper headline, EVACUATION, at one point -- why was he left behind? How did he survive unattended for 28 days with only an IV drip that would have run out in a few hours? If the rest of the world is safe and only Britain is quarantined, why doesn't Frank's radio pick up international broadcasts? Where are the humanitarian operations like the World Health Organization and Doctors Without Borders? And so on....

*The infected in 28 Days Later aren't technically zombies. i.e. animated dead people. They're still alive, and they can be killed by ordinary means like shooting or stabbing them.

Wednesday, March 15, 2017

Madadayo (Akira Kurosawa, 1993)

|

| Tatsuo Matsumura in Madadayo |

Uchida's Wife: Kyoko Kagawa

Takayama: Hisashi Igawa

Amaki: George Tokoro

Kiriyama: Masayuki Yui

Sawamura: Akira Terao

Dr. Kobayashi: Takeshi Kusaka

Rev. Kameyama: Asei Kobayashi

Tada: Mitsuru Hirata

Kitamura: Takao Zushi

Ota: Nobuto Okamoto

Director: Akira Kurosawa

Screenplay: Akira Kurosawa, Ishiro Honda

Cinematography: Takao Saito, Shoji Ueda

Art direction: Yoshiro Muraki

Film editing: Akira Kurosawa, Ishiro Honda

Music: Shinichiro Ikebe

Akira Kurosawa's Madadayo isn't quite the autumnal masterpiece we want a great director's final film to be, but it has a suitably valedictory tone. It's a portrait of a kind of Japanese Mr. Chips, a teacher so beloved that his students reunite every year to celebrate his birthday with lots of singing and drinking. The film is based on the life of Hyakken Uchida, an actual professor of German at Hosei University in Tokyo. We never really see what made Uchida so beloved by his students: The film opens with his retirement from teaching so he can devote more time to writing, but we can infer from the genial, eccentrically bookish manner that peeps through his professorial sternness that he has always been a favorite of his students, often drinking with them after hours. The narrative (such as it is -- Kurosawa's screenplay, based on the real Uchida's essays, has no real plot or dramatic arc) picks up on his birthday in 1943, when his former students help him and his wife move into a new house. When the house is destroyed by fire from the American bombing, Uchida and his wife move into a tiny shed that was an outbuilding on a wealthy man's estate and live there until after the war, when his students build a new house for him. We see him celebrate his 60th birthday with his students at a banquet that grows so noisy some GIs from the occupying forces arrive in a Jeep to check it out but leave with smiles on their faces. He's so beloved that when a rich man proposes to build a three-story house across the street from him, thereby casting Uchida's house and garden in shadow, the man selling the land reneges on the deal and then sells it to a group of the ex-students. The greatest crisis in his life is not the war but the loss of a beloved cat, who wanders off one day, causing him so much grief that his wife calls in the students to help find it. Eventually, a new cat takes up with Uchida and life goes on. At the film's end, Uchida collapses from a heart arrhythmia at the banquet celebrating his 77th birthday, but even then he calls out the phrase "Mada dayo!" ("Not yet!"), which has become his ritual defiance of death at his birthday celebrations. Matsumura's performance sustains the film, which at 2 hours and 14 minutes is overlong and more a film for Kurosawa completists than for general audiences. The birthday celebrations become wearyingly exuberant, and the search for the lost cat seems to go on forever, but the film is lightened by Kurosawa's sense of humor and his affection for the characters. It also touches on the changes in Japanese society over the years: The classroom scene at the beginning has a militaristic formality, and the drinking bouts of the early birthday celebrations are all-male affairs. But by the end, not only has Uchida's ever-dutiful wife joined in the celebration, but his students' wives, children, and grandchildren are present, too.

Tuesday, March 14, 2017

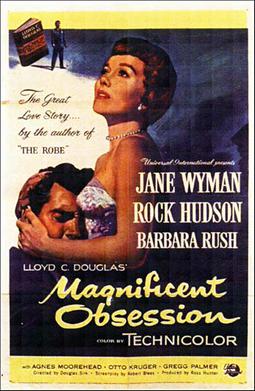

Magnificent Obsession (Douglas Sirk, 1954)

Lloyd C. Douglas, Lutheran pastor turned novelist, was in some ways the anti-Ayn Rand. His Magnificent Obsession, published in 1929 and first filmed in 1935 with Irene Dunne and Robert Taylor directed by John M. Stahl, advocates a kind of "pay it forward" altruism, the obverse of Rand's laissez-faire individualism. Douglas preached a gospel of service to others with no expectation of rewards to oneself. Fortunately, director Douglas Sirk and screenwriters Robert Blees and Wells Root keep the preaching in the 1954 remake down to a minimum -- mostly confining it to the preachiest of the film's characters, the artist Edward Randolph (Otto Kruger), but also using it as an essential element in the development of the central character, Bob Merrick (Rock Hudson), in his transition from heel to hero. This was Hudson's first major dramatic role, the one that launched him from Universal contract player into stardom. Not coincidentally, it was the second of nine films he made with Sirk, movies that range from the negligible Taza, Son of Cochise (1954) to the near-great Written on the Wind (1956). More than anyone, perhaps, Sirk was responsible for turning Hudson from just a handsome hunk with a silly publicist-concocted name into a movie actor of distinct skill. In Magnificent Obsession he demonstrates that essential film-acting technique: letting thought and emotion show on the face. It's a more effective performance than that of his co-star, Jane Wyman, though she was the one who got an Oscar nomination for the movie. As Helen Phillips, whose miseries are brought upon her by Merrick (through no actual fault of his own), Wyman has little to do but suffer stoically and unfocus her eyes to play blind. Hudson has an actual character arc to follow, and he does it quite well -- though reportedly not without multiple takes of his scenes, as Sirk coached him into what he wanted. What Sirk wanted, apparently, is a lush, Technicolor melodrama that somehow manages to make sense -- Sirk's great gift as a director being an ability to take melodrama seriously. Magnificent Obsession, like most of Sirk's films during the 1950s, was underestimated at the time by serious critics, but has undergone reevaluation after feminist critics began asking why films that center on women's lives were being treated as somehow inferior to those about men's. It's not, I think, a great film by any real critical standards -- there's still a little too much preaching and too much angelic choiring on the soundtrack, and the premise that a blind woman assisted by a nurse (Agnes Moorehead) with bright orange hair could elude discovery for months despite widespread efforts to find them stretches credulity a little too far. But it's made and acted with such conviction that I found myself yielding to it anyway.

Monday, March 13, 2017

Passing Fancy (Yasujiro Ozu, 1933)

|

| Den Obinata and Takeshi Sakamoto in Passing Fancy |

Sunday, March 12, 2017

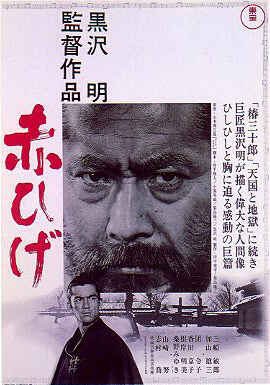

Red Beard (Akira Kurosawa, 1965)

The influence of American movies on the work of Akira Kurosawa is well-known. His viewings of American Westerns, for example, helped shape such classics as Seven Samurai (1954) and Yojimbo (1961). But Red Beard seems to me an instance in which the influence wasn't so fortunate. It's a kind of reworking of MGM's series of Dr. Kildare movies of the 1930s and '40s, in which the ambitious young intern Dr. Kildare tangles with the crusty older physician Dr. Gillespie and thereby learns a few lessons -- a dynamic that persists today in TV series like Grey's Anatomy and soap operas like General Hospital. In Red Beard, ambitious young Dr. Noboru Yasumoto (Yuzo Kayama) is sent to work under crusty older Dr. Kyojo Niide (Toshiro Mifune), known as "Red Beard" for an obvious facial feature. It's the 19th century, the last years of the Tokugawa shogunate, and Yasumoto, having finished his studies in Nagasaki, expects that the influence of his father, a prominent physician, will land him a role as the shogun's personal physician. He's angry when he finds that he's been sent to a rural clinic that mainly serves the poor. There is one affluent patient at the clinic, however: a young woman known as "The Mantis" (Kyoko Kagawa) because she stabbed two of her lovers to death. Her wealthy father has built a house for her on the grounds of the clinic, but only Red Beard is allowed to approach and treat her. Yasumoto initially rebels against the assignment, feeling disgust for the patients: When he asks the physician he's replacing at the clinic what smells like "rotten fruit," he's told that that's the way the poor smell. But eventually (and predictably), he learns to respect the work of Red Beard and to value the lives of his patients. Red Beard is hardly a bad movie: Kurosawa brilliantly stages the first encounter of Yasumoto and The Mantis, who has escaped from her house, in a carefully framed sequence, a long take in which the doctor and the madwoman begin at opposite sides of the wide screen -- it's filmed in Tohoscope, an anamorphic process akin to Cinemascope -- with a tall candlestick between them. Gradually, accompanied by slow camera movements, the two approach each other, the doctor trying to gauge the motives and the sanity of the young woman. Finally the calm framing of the scene is shattered into a series of quick cuts, as she attacks with a pair of scissors, and the scene ends with a brief shot of Red Beard suddenly opening the door. Red Beard was shot by two acclaimed cinematographers, Asakazu Nakai and Takao Saito, both of whom frequently worked with Kurosawa, and the production design was by Yoshiro Muraki, who fulfilled Kurosawa's exacting demands for meticulous faithfulness to the period, including the construction of what was virtually a small village, using only materials that would have been available in the period. But what keeps Red Beard from the first rank of Kurosawa's films, I think, is the sentimental moralizing, the insistence of having the characters "learn lessons." Yasumoto, having learned his initial lesson about valuing the lives of the poor, is given a young patient, Otoyo (Terumi Niki), rescued from a brothel where she has essentially gone feral. (During the rescue scene, Kurosawa can't resist having his longtime star Mifune show off some of his old chops: The doctor takes on a gang of thugs outside the brothel and single-handedly leaves them with broken arms, legs, and heads. It's a fun scene, but not particularly integral to the character.) When Yasumoto has succeeded in teaching Otoyo to respond to kindness, it then becomes her turn to teach others what she has learned. The moralizing overwhelms the film, leaving us longing for the deeper insight into the characters found in films by Kurosawa's great contemporaries Yasujiro Ozu and Kenji Mizoguchi.

Saturday, March 11, 2017

Moonlight Serenade (Masahiro Shinoda, 1997)

Moonlight Serenade is an entertaining mélange of several genres: historical drama, coming-of-age tale, and family drama, with a touch of road movie and two romantic subplots, all kept more or less in focus by a framing story that turns it into a film about the endurance of the Japanese people in the face of everything that life can throw at them. It begins with Keita Onda (Kyozo Nagatsuka), a man in his 60s, watching the news reports about the 1995 earthquake that devastated Kobe. The film flashes back to 10-year-old Keita (Hideyuki Kasahara) watching, from a safe distance, the red sky over a burning Kobe after an American air raid. Like the other boys watching the fiery sky, who claim that the sight gives them an erection, Keita is more excited than frightened. Then the war ends, and Keita's family is marshaled his father, Koichi (also played by Nagatsuka), into a difficult journey from Awaji, where they now live, to the ancestral home in Kyushu. Keita is entrusted with seeing after the box that supposedly contains the ashes of his elder brother, who enlisted in the Japanese navy at 17 and was killed two years later when his ship hit a mine. (What the box actually contains is one of the film's surprises.) The family also consists of Koichi's wife, Fuji (Shima Iwashita), and their 18-year-old son, Koji (Jun Toba), and small daughter, Hideko (Sayuri Kawauchi). The neighbors are astonished that anyone should be making such a perilous trip across American-occupied Japan; the trains are unreliable and overcrowded and ships are still prey to undetonated mines. Gossip builds that Koichi, a tough police officer and a notoriously hidebound traditionalist, intends for his family to commit ritual suicide when they reach the ancestral burial place. The journey is in fact difficult and often suspenseful, but director Masahiro Shinoda, working from a screenplay by Katsuo Naruse from a novel by Yu Aku, maintains a light touch, infusing the difficult journey with humor. The film develops a love interest for Koji in the form of Yukiko (Hinano Yoshikawa), an orphaned girl who is also going to Kyushu, to live with relatives she has never seen. Koji, who hates his father, plans to run away somewhere along the journey, and when he meets Yukiko, he tries to persuade her to join him. A group of secondary characters joins the family on shipboard, including a black marketer (Junji Takada), whose stash of whiskey helps break down Koichi's stiff reserve (along with his policeman's distaste for the black market), and a traveling film exhibitor whose collection of movies includes some illicit samurai films that have been banned by the occupying Americans for their militarism. Keita, naturally, is enchanted by the movies, and there's a charming scene late in the film in which he goes to a theater to see Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1942) with his father. Unfortunately, Keita can't follow the American romance -- some of the words in the Japanese subtitles are too hard for him, he says -- and his father only says he'll have to be older to understand it. Moonlight Serenade is one of the late films by Shinoda, who apprenticed with Yasujiro Ozu and became a prominent member of the "Japanese New Wave" in the 1960s. It displays his skill at storytelling, handling several subplots and surprises, and has a fine sympathetic treatment of the people caught up in the postwar crisis. But it's a bit old-fashioned for a movie made in the 1990s, too overloaded with characters and incidents for its own good, and the frame story seems unnecessary.

Friday, March 10, 2017

The Ladykillers (Alexander Mackendrick, 1955)

The British used to like to think of themselves as congenitally disposed to law and order -- so much so that they didn't need a written constitution to maintain it. Crime, when it happened, was presumed to follow rules of decorum, or at least that's the case in countless "cozy" murder mysteries like Agatha Christie's Miss Marple series. The trend reached its peak in the Ealing Studios comedies featuring Alec Guinness in the 1950s: Kind Hearts and Coronets (Robert Hamer, 1949), The Lavender Hill Mob (Charles Crichton, 1951), and The Ladykillers. Murder and larceny are treated almost as genteel, if eccentric, pursuits, avoiding violence unless it becomes unpleasantly necessary. It's significant that the most menacingly violent member of the crew that pulls off the robbery in The Ladykillers speaks with a foreign accent and is played by the Czech-born actor Herbert Lom, as if only a foreigner would think of killing the sweet old lady (Katie Johnson) who threatens to reveal their crime to the police. It's possible, too, that the mastermind of the crew, Prof. Marcus (Guinness), is not entirely British -- his surname has foreign overtones -- although the oversize false teeth Guinness wears do seem like the product of British dentistry. The Ladykillers is a wry tribute to the Britain that had just muddled through World War II and was emerging from postwar austerity. The house in which Mrs. Wilberforce lives, perched precariously on the brink of a railway tunnel, has had its upper stories condemned as unsafe after the wartime bombing, but it's filled with tributes to the Empire that was crumbling as steadily as the house. She lives alone, guarded only by her late husband's parrots, which he had rescued from the ship he went down on, and by the local constabulary, who tolerate her frequent visits to the station to report things like a neighbor's sighting of a flying saucer. She is obviously an easy mark, however, for Prof. Marcus and his gang: Claude (Cecil Parker), Louis (Lom), Harry (Peter Sellers), and the punchy ex-boxer One-Round (Danny Green), who pose as a string quintet practicing in the rooms Marcus leases in her house. (They play a recording of a Boccherini minuet while they plot the heist, and afterward stash the loot in their instrument cases.) Naturally, they bumble themselves into revealing their secret to Mrs. Wilberforce, and after deciding that they must kill her to protect themselves manage to bumble themselves into killing one another instead. As usual with Ealing Studios comedies, the acting is uniformly delightful: Guinness said he modeled his character on Alastair Sim, for whom the role was originally intended, and it's fun to see Sellers and Lom together some years before their re-teaming in the Pink Panther films. Interestingly, this tribute to the Brits was written by an American, William Rose, who received an Oscar nomination for his screenplay. Rose had stayed on in England and married an Englishwoman after service in World War II. Otto Heller's color cinematography and Jim Morahan's art direction add greatly to the success of the film.

Thursday, March 9, 2017

Every-Night Dreams (Mikio Naruse, 1933)

|

| Tatsuo Saito and Sumiko Kurishima in Every-Night Dreams |

Wednesday, March 8, 2017

Carol (Todd Haynes, 2015)

With her Mamie Eisenhower bangs and heart-shaped face, Rooney Mara in Carol becomes the reincarnation of such '50s icons as Audrey Hepburn, Jean Simmons, and Maggie McNamara -- particularly the McNamara of The Moon Is Blue (Otto Preminger, 1953), that once-scandalous play and movie about a young woman who defies convention by talking openly about sex while retaining her virginity. It's just coincidence that Carol is set at the end of 1952 and into 1953, the year of the release of The Moon Is Blue, but the juxtaposition of McNamara's Patty O'Neill and Mara's Therese Belivet seems to me appropriate because the 1950s have become such a touchstone for examining our attitudes toward sex. Director Todd Haynes and screenwriter Phyllis Nagy, adapting a novel by Patricia Highsmith, have done an exemplary job in Carol of not tilting the emphasis toward Grease-style caricature or Mad Men-style satire of the era, or exploiting the same-sex relationship in the film for sensationalism or statement-making. Carol is a story about people in relationships, clear-sightedly viewed in a way that Therese herself would endorse. After asking her boyfriend Richard (Jake Lacy) if he's ever been in love with a boy and receiving a shocked reply that he's only "heard of people like that," Therese replies, "I don't mean people like that. I just mean two people who fall in love with each other." It's this matter-of-factness that the film tries to maintain throughout its story of Therese and Carol (Cate Blanchett), the well-to-do wife in a failing marriage. That the film is set in the 1950s, when cracks were showing in the conventional attitudes toward both marriage and homosexuality, gives piquancy to their relationship, but it doesn't limit it. The story could be (and probably is) playing itself out today in various combinations of sexual identity. The film works in large part because of the steadiness of Haynes at the helm, with two extraordinary actresses at the center and beautiful support from Sarah Paulson as Abby, Carol's ex-lover, and Kyle Chandler (one of those largely unsung actors like the late Bill Paxton who make almost everything they appear in better) as Carol's husband, the hard-edged Harge Aird. The sonic texture of the 1950s is splendidly provided by Carter Burwell's score and a selection of classic popular music by artists like Woody Herman, Georgia Gibbs, Les Paul and Mary Ford, Perry Como, Eddie Fisher, Patti Page, Jo Stafford, and Billie Holiday.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)