A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Tuesday, March 21, 2017

Story of a Love Affair (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1950)

The Battle of Algiers (Gillo Pontecorvo, 1966)

|

| Jean Martin in The Battle of Algiers |

Monday, March 20, 2017

No post today

Doing my taxes. For the record, I watched The Battle of Algiers (Gillo Pontecorvo, 1966) last night.

Sunday, March 19, 2017

Naked (Mike Leigh, 1993)

Midway through the film, Johnny (David Thewlis) happens upon a parked limousine whose driver is dozing at the wheel. Waking up, the driver mistakes Johnny for his client and invites him into the limo, only to realize his mistake suddenly and order Johnny out. He's one of the few lucky ones in Naked: Lots of other people invite Johnny in, only to realize their mistake after he's wrought chaos in their lives. For Johnny is less a realistic character than a symbolic force: the spirit of anarchy loose in a world that's trying to impose something like order. Johnny is something of a Shakespearean fool, licensed to deflate pomposity, to expose absurdities like the meaningless job of Brian (Peter Wight), the security guard for an empty building: "You're guarding space? That's stupid, innit? Because someone could break in there and steal all the fuckin' space and you wouldn't know it's gone, would you?" Writer-director Mike Leigh typically begins his filmmaking in disorder -- sessions in which the actors improvise what their characters are like, what they might do or say in a given situation, and how their interrelationships might work out -- and ends in order -- a scripted film in which the actors are not allowed to deviate from what's on the page. He is fortunate in Naked to have had a brilliant company, headed by Thewlis, to find out what's in their characters. In Naked, Johnny is reading James Gleick's Chaos, which posits an underlying pattern to what appears random and chaotic. Johnny is the butterfly flapping its wings that causes a storm to sweep through the lives of flatmates Louise (Lesley Sharp), Sophie (Katrin Cartlidge), and Sandra (Claire Skinner) -- not that they don't already lead lives of quiet (and sometimes noisy) desperation. It can be argued, however, that Johnny, for all his sponging amorality and his sexual aggression, represents something of a life force in the film, especially when contrasted with the rich and predatory Jeremy (Greg Crutwell), a character Leigh introduces I think intentionally to serve as a foil for Johnny, who at least has a measure of self-awareness even if sometimes it has to be beaten into him. Never let it be said that Leigh uses nudity gratuitously: It's gym-toned Jeremy who stays snugly encased in his designer briefs but scrawny Johnny who strides boldly toward the camera, genitals aflop. Viciously funny, tonically brutal, Naked is one of those wake-up-call films we need to subject ourselves to now and then.

Saturday, March 18, 2017

A Face in the Crowd (Elia Kazan, 1957)

|

| Andy Griffith in A Face in the Crowd |

Marcia Jeffries: Patricia Neal

Joey DePalma: Anthony Franciosa

Mel Miller: Walter Matthau

Betty Lou Fleckum: Lee Remick

Gen. Haynesworth: Percy Waram

Macey: Paul McGrath

Sen. Worthington Fuller: Marshall Neilan

Director: Elia Kazan

Screenplay: Budd Schulberg

Cinematography: Gayne Rescher, Harry Stradling Sr.

I don't know if TCM intentionally "counterprogrammed" the Trump inauguration by scheduling Elia Kazan's film about a faux-populist demagogue on the same day as the ceremony, but it sure looks like it, and I approve. Like Trump, A Face in the Crowd's Larry "Lonesome" Rhodes is a product of the media's amoral pursuit of the colorful character, a man lifted to uncommon power by those entertained by the flamboyance and vulgarity. Rhodes (perhaps like Trump) isn't so much the villain of Budd Schulberg's story and screenplay as are his enablers, Marcia Jeffries and Mel Miller, and his exploiters, like Joey DePalma, who enrich themselves while discovering the previously untapped potential of mass media. In 1957, this potential was just beginning to be realized, but 60 years later it had taken a dangerous man to the White House. I don't think Kazan and Schulberg fully realized that possibility, just as Sidney Lumet and Paddy Chayefsky didn't fully realize the prescience of Network (Lumet, 1976). Both films should serve as a permanent warning that today's satire is tomorrow's nightmare. A Face in the Crowd is an important film without being a great one. Schulberg's screenplay falls apart in the middle, and the denouement in which Marcia somehow comes to her senses and exposes Rhodes as a fraud is awkward and mechanical, largely because Marcia herself is something of a mechanical character. An actress of considerable skill, Patricia Neal does what she can to make the character live, but the words aren't there in the script to explain why she tolerates Rhodes's fraudulence as long as she does. Walter Matthau and Anthony Franciosa come off a little better because their roles are written as stereotypes: Cynical Writer and Go-getting Hot Shot. So the film really belongs to Andy Griffith, who parlays his dead-eyed shark's grin into something that should have been the foundation of a career with more highlights than a folksy sitcom and an old-fart detective show. It's a charismatic but ragged performance that needed a little more shaping from writer and director, something that Kazan admitted to himself in his diaries when he wrote about Rhodes and the film, "The complexity ... was left out." Rather than having Rhodes revealed as a fraud to his followers, Kazan said, Rhodes should have been allowed to recognize that he had been trapped by his own fraudulence. Deprived of anagnorisis, a moment of tragic self-recognition, Rhodes becomes a figure of melodrama, bellowing "Marcia!" from the balcony at the end but probably fated to make what Miller suggests to him, the comeback of a has-been. Fortunately, Kazan and Schulberg were wise enough to change their original ending, in which Rhodes commits suicide -- there's not enough tragedy in their conception of the character for that.

Friday, March 17, 2017

Osaka Elegy (Kenji Mizoguchi, 1936)

It's easy to imagine Kenji Mizoguchi's Osaka Elegy remade into a 1930s "women's picture" starring Bette Davis, except that nothing made in Hollywood under the infantilizing Production Code would have had the depth and insight into the real problems of women that Mizoguchi's film does. Mizoguchi's direction frames the story elegantly: He begins with a shot of the neon-lighted city, backed by the pop standard "Stairway to the Stars" on the soundtrack, as day gradually breaks and the glamour of the neon fades into the drab reality of the daytime city. We go to the home of Sonosuke Asai (Benkei Shiganoya), the head of a large pharmaceuticals company, where he berates the maids for small infractions and quarrels with his shrewish wife, Sumiko (Yoko Umemura). The opening sets a tone of disillusionment that pervades the entire film, which becomes a sharp commentary on both traditional and contemporary sexual roles. The film's protagonist is Ayako (Isuzu Yamada), switchboard operator at Asai Pharmaceuticals, whom Asai wants to become his mistress. Ayako is reluctant -- she has a boyfriend, Nishimura (Kensaku Hara), another employee at the company -- but her feckless father (Shinpachiro Asaka) has been skimming from the till at work and has lost the money in the stock market. So she quits her job, lets Asai set her up in a fancy modern apartment, and sends her father the money he needs. After Asai's wife uncovers the arrangement, a friend of Asai's, Fujino (Eitaro Shindo), tries to move in on Ayako. But Ayako reconnects with Nishimura, who proposes to her. Uncertain how he will respond to the truth about her life -- she has told him she works in a beauty parlor -- she postpones her answer. Then she learns from her younger sister that their brother is being forced to drop out of the university because her father can't pay the tuition. She gets the money by pretending to yield to Fujino's advances, but runs to Nishimura and agrees to marry him, while also confessing her liaison with Asai. As Nishimura is pondering this information, a furious Fujino arrives and after being turned away, calls the police, charging her with theft. Nishimura cravenly tells the police that he was innocently dragged into the affair by Ayako, but because it's her first offense she is released into her father's custody. Her family, whose money problems she has dutifully solved, shuns her and her brother calls her a "delinquent." Ayako walks out into the night and we follow her to a bridge, where she looks down into the trash-filled waters. But as we wonder if she is going to commit suicide, the family doctor, who has been present at several of the crisis points in her story, happens to meet her on the bridge. She asks him if there is a cure for delinquency, and when he says no, she accepts the judgment and, holding her head high, walks away toward the camera. Yamada's terrific performance was one of several she gave for Mizoguchi, establishing her as a specialist in strong female roles -- she is perhaps best-known by Western audiences as the Lady Macbeth equivalent in Akira Kurosawa's Throne of Blood (1957).

Thursday, March 16, 2017

28 Days Later (Danny Boyle, 2002)

|

| Cillian Murphy in 28 Days Later |

Selena: Naomie Harris

Frank: Brendan Gleeson

Major Henry West: Christopher Eccleston

Hannah: Megan Burns

Mark: Noah Huntley

Sgt. Farrell: Stuart McQuarrie

Corporal Mitchell: Ricci Harnett

Director: Danny Boyle

Screenplay: Alex Garland

Cinematography: Anthony Dod Mantle

Production design: Mark Tildesley

Danny Boyle's science fiction/horror film 28 Days Later was a critical and commercial success, which owes much, I suspect, to its post-apocalyptic theme, capturing a mood prevalent after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. Many viewers noted the similarity of the kiosk in the film, covered with notices posted by people searching for lost friends and relatives, to the real ones posted in New York City after the fall of the World Trade Center towers -- a prescient touch on the part of the filmmakers, since the scene was shot before the terrorist attack and its aftermath. It has also been an influential film, helping spark an interest in "zombie"* movies and TV shows. After a prologue that shows how animal-rights activists attacked a research laboratory and unwittingly released a virus that causes uncontrollable rage in its victims and is spread by contact with blood and saliva, the film's protagonist, Jim, wakes up from a coma in a London hospital to discover that he has been abandoned there and that the streets outside are empty. (The premise of someone waking up from a coma to discover a world depopulated by an incurable virus was repeated by the creators of The Walking Dead, first for the graphic novel published in 2003 and later for the TV series that began in 2010.) Jim soon discovers that he is not entirely alone: He is attacked by people infected with the virus and rescued by two who weren't: Selena and Mark. Unfortunately, Mark gets bitten by one of the infected and has to be killed, allowing Selena to explain that the disease takes hold swiftly and is incurable. Selena and Jim then discover two more survivors, Frank and his daughter, Hannah, who have a crank-operated radio that has picked up a signal from survivors north of Manchester calling for others to join them. Frank is infected and killed during their perilous drive northward, and Jim, Selena, and Hannah discover that the survivors are in a well-armed military outpost under the command of Maj. Henry West. It turns out that West has been sending out the signals especially to attract women to service his sex-starved troops, which means not only that Selena and Hannah are in danger of rape but also that Jim is expendable. Before he helps Selena and Hannah escape, Jim also hears the theory of a soldier opposed to West that the virus has not in fact spread worldwide: that it has been contained in other countries and that the island of Britain is quarantined -- a theory that Jim confirms for himself when he sees the contrails of a jet plane flying high overhead. The released film ends happily -- or at least hopefully -- when Jim, Selena, and Hannah, having escaped, construct a giant "HELLO" sign that is spotted by a plane flying reconnaissance over the cottage where they live. It's not the preferred ending of director Boyle and screenwriter Alex Garland, who proposed a bleaker resolution of the story that failed with test audiences. Well-directed and -acted, 28 Days Later does what it's designed to do: build suspense and provide interesting characters. It also resonates nicely with our paranoia about pandemic infections in the age of HIV, Ebola, and the annual influenza scare. But it doesn't hold up well under the old test of Questions You're Not Supposed to Ask: like, why has Jim been abandoned, stark naked and comatose, in a hospital? If the hospital was attacked by the infected, why wasn't he attacked? If it was evacuated -- we see a newspaper headline, EVACUATION, at one point -- why was he left behind? How did he survive unattended for 28 days with only an IV drip that would have run out in a few hours? If the rest of the world is safe and only Britain is quarantined, why doesn't Frank's radio pick up international broadcasts? Where are the humanitarian operations like the World Health Organization and Doctors Without Borders? And so on....

*The infected in 28 Days Later aren't technically zombies. i.e. animated dead people. They're still alive, and they can be killed by ordinary means like shooting or stabbing them.

Wednesday, March 15, 2017

Madadayo (Akira Kurosawa, 1993)

|

| Tatsuo Matsumura in Madadayo |

Uchida's Wife: Kyoko Kagawa

Takayama: Hisashi Igawa

Amaki: George Tokoro

Kiriyama: Masayuki Yui

Sawamura: Akira Terao

Dr. Kobayashi: Takeshi Kusaka

Rev. Kameyama: Asei Kobayashi

Tada: Mitsuru Hirata

Kitamura: Takao Zushi

Ota: Nobuto Okamoto

Director: Akira Kurosawa

Screenplay: Akira Kurosawa, Ishiro Honda

Cinematography: Takao Saito, Shoji Ueda

Art direction: Yoshiro Muraki

Film editing: Akira Kurosawa, Ishiro Honda

Music: Shinichiro Ikebe

Akira Kurosawa's Madadayo isn't quite the autumnal masterpiece we want a great director's final film to be, but it has a suitably valedictory tone. It's a portrait of a kind of Japanese Mr. Chips, a teacher so beloved that his students reunite every year to celebrate his birthday with lots of singing and drinking. The film is based on the life of Hyakken Uchida, an actual professor of German at Hosei University in Tokyo. We never really see what made Uchida so beloved by his students: The film opens with his retirement from teaching so he can devote more time to writing, but we can infer from the genial, eccentrically bookish manner that peeps through his professorial sternness that he has always been a favorite of his students, often drinking with them after hours. The narrative (such as it is -- Kurosawa's screenplay, based on the real Uchida's essays, has no real plot or dramatic arc) picks up on his birthday in 1943, when his former students help him and his wife move into a new house. When the house is destroyed by fire from the American bombing, Uchida and his wife move into a tiny shed that was an outbuilding on a wealthy man's estate and live there until after the war, when his students build a new house for him. We see him celebrate his 60th birthday with his students at a banquet that grows so noisy some GIs from the occupying forces arrive in a Jeep to check it out but leave with smiles on their faces. He's so beloved that when a rich man proposes to build a three-story house across the street from him, thereby casting Uchida's house and garden in shadow, the man selling the land reneges on the deal and then sells it to a group of the ex-students. The greatest crisis in his life is not the war but the loss of a beloved cat, who wanders off one day, causing him so much grief that his wife calls in the students to help find it. Eventually, a new cat takes up with Uchida and life goes on. At the film's end, Uchida collapses from a heart arrhythmia at the banquet celebrating his 77th birthday, but even then he calls out the phrase "Mada dayo!" ("Not yet!"), which has become his ritual defiance of death at his birthday celebrations. Matsumura's performance sustains the film, which at 2 hours and 14 minutes is overlong and more a film for Kurosawa completists than for general audiences. The birthday celebrations become wearyingly exuberant, and the search for the lost cat seems to go on forever, but the film is lightened by Kurosawa's sense of humor and his affection for the characters. It also touches on the changes in Japanese society over the years: The classroom scene at the beginning has a militaristic formality, and the drinking bouts of the early birthday celebrations are all-male affairs. But by the end, not only has Uchida's ever-dutiful wife joined in the celebration, but his students' wives, children, and grandchildren are present, too.

Tuesday, March 14, 2017

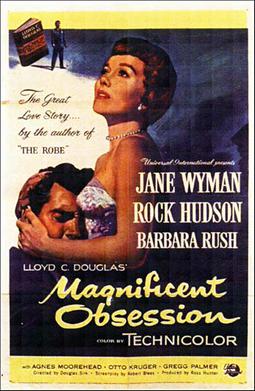

Magnificent Obsession (Douglas Sirk, 1954)

Lloyd C. Douglas, Lutheran pastor turned novelist, was in some ways the anti-Ayn Rand. His Magnificent Obsession, published in 1929 and first filmed in 1935 with Irene Dunne and Robert Taylor directed by John M. Stahl, advocates a kind of "pay it forward" altruism, the obverse of Rand's laissez-faire individualism. Douglas preached a gospel of service to others with no expectation of rewards to oneself. Fortunately, director Douglas Sirk and screenwriters Robert Blees and Wells Root keep the preaching in the 1954 remake down to a minimum -- mostly confining it to the preachiest of the film's characters, the artist Edward Randolph (Otto Kruger), but also using it as an essential element in the development of the central character, Bob Merrick (Rock Hudson), in his transition from heel to hero. This was Hudson's first major dramatic role, the one that launched him from Universal contract player into stardom. Not coincidentally, it was the second of nine films he made with Sirk, movies that range from the negligible Taza, Son of Cochise (1954) to the near-great Written on the Wind (1956). More than anyone, perhaps, Sirk was responsible for turning Hudson from just a handsome hunk with a silly publicist-concocted name into a movie actor of distinct skill. In Magnificent Obsession he demonstrates that essential film-acting technique: letting thought and emotion show on the face. It's a more effective performance than that of his co-star, Jane Wyman, though she was the one who got an Oscar nomination for the movie. As Helen Phillips, whose miseries are brought upon her by Merrick (through no actual fault of his own), Wyman has little to do but suffer stoically and unfocus her eyes to play blind. Hudson has an actual character arc to follow, and he does it quite well -- though reportedly not without multiple takes of his scenes, as Sirk coached him into what he wanted. What Sirk wanted, apparently, is a lush, Technicolor melodrama that somehow manages to make sense -- Sirk's great gift as a director being an ability to take melodrama seriously. Magnificent Obsession, like most of Sirk's films during the 1950s, was underestimated at the time by serious critics, but has undergone reevaluation after feminist critics began asking why films that center on women's lives were being treated as somehow inferior to those about men's. It's not, I think, a great film by any real critical standards -- there's still a little too much preaching and too much angelic choiring on the soundtrack, and the premise that a blind woman assisted by a nurse (Agnes Moorehead) with bright orange hair could elude discovery for months despite widespread efforts to find them stretches credulity a little too far. But it's made and acted with such conviction that I found myself yielding to it anyway.

Monday, March 13, 2017

Passing Fancy (Yasujiro Ozu, 1933)

|

| Den Obinata and Takeshi Sakamoto in Passing Fancy |

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)