A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Tuesday, January 31, 2017

The Hateful Eight (Quentin Tarantino, 2015)

The title, The Hateful Eight, is pretty clearly an homage of sorts to such films as The Magnificent Seven (John Sturges, 1960), The Dirty Dozen (Robert Aldrich, 1967), and even The Wild Bunch (Sam Peckinpah, 1969). And it's well to remember how all of those films were once criticized for excessive violence and The Wild Bunch was once threatened with an NC-17 rating. None of them contained anything like the violence of The Hateful Eight, which is visited on all of the characters, but most memorably on the one woman among the eight: Daisy Domergue (Jennifer Jason Leigh), who is subjected to torrents of blood, vomit, and blown-out brains along with repeated blows to the face and a final drawn-out hanging. Writer-director Quentin Tarantino and his defenders excuse the excess of violence by arguing that his cinematic violence is a metaphor for racial and sexual violence in America and an expression of the revenge mentality that undermines the due administration of justice. As Oswaldo Mobray (Tim Roth) argues in the film, "dispassion is the very essence of justice. For justice delivered without dispassion is always in danger of not being justice." That Mobray is using this argument to forestall any actual dispassionate justice meted out to him only reinforces its irony -- a kind of postmodern irony that some will argue tends to lead us into spirals of self-defeat. That's why Tarantino's films often feel so nihilistic, despite their wit and technical prowess. At more than three hours, The Hateful Eight is about an hour too long, which I think is a fatal flaw, considering that the suspense lags as the slow revelation of its plot twists emerges. The wait for the eruptions of violence that we know are coming produces a kind of prurience, but there is no cathartic release when they arrive. The movie is well-acted by Leigh, Roth, Samuel L. Jackson, Kurt Russell, Walton Goggins, Demián Bichir, Bruce Dern, and Michael Madsen as the eight, and Channing Tatum gives a remarkable performance in his late surprise appearance. The music by Ennio Morricone won a well-deserved, long overdue Oscar, and the cinematography by Robert Richardson makes the most of the shift from spectacular mountain scenery to the claustrophobic setting of the major part of the film. But Tarantino has settled into predictability, and I want him to show us something new.

Monday, January 30, 2017

Mulholland Dr. (David Lynch, 2001)

Mulholland Dr. defies exegesis like no other film I know. Sure, you can trace its origins: Car-crash amnesia is a soap-opera trope; the mysterious mobsters and other manipulators are film noir staples; the portrayal of Hollywood as a nightmare dreamland is straight from Sunset Blvd. (Billy Wilder, 1950), which the film even imitates by having its before-the-credits title appear on a street sign. But writer-director David Lynch isn't out to parody the sources -- not entirely, anyway. What he is up to is harder to pinpoint. There's a part of me that thinks Lynch just wants to have fun -- a nasty kind of fun -- manipulating our responses. At the beginning, we're on to him in that regard: We laugh at the minimal conversation between the two detectives (Robert Forster and Brent Briscoe) at the crash site. We recognize the naive awe on the face of Betty Elms (Naomi Watts), as she arrives in Los Angeles, as a throwback to the old Hollywood musicals in which choruses of hopefuls arrive at the L.A. train station singing "Hooray for Hollywood!" (Has anyone ever been inspired to sing and dance when arriving at LAX?) We're delighted by the appearance of Ann Miller as the landlady, just as later we identify Lee Grant, Chad Everett, and even Billy Ray Cyrus in their cameos. Even the seemingly disjointed scenes -- the director, Adam Kesher (Justin Theroux), is bullied by the Castiglianes (Dan Hedaya and the film's composer, Angelo Badalamenti), or a man (Patrick Fischler) recounts his nightmare at a restaurant called Winkie's, or a hit man (Mark Pellegrino) murders three people -- are standard thriller stuff, designed to keep us guessing -- though at that point, having seen this sort of thing in films by Quentin Tarantino and others, we feel confident that everything will fit together. And then, suddenly, it doesn't. Betty vanishes and Diane Selwyn (Watts), whom we have thought dead, is alive. The amnesia victim known as Rita (Laura Harring) is now Camilla Rhodes, the movie star that Betty wanted to be, and Diane, Camilla's former lover, wants to kill her. It's such a complete overthrow of conventional narrative that there are really only two basic responses, neither of them quite sufficient: One is to dismiss the film as a wacked-out experiment in playing with the audience -- "a load of moronic and incoherent garbage," in the words of Rex Reed -- or to try to assimilate it into some coherent and consistent scheme, like the theory that the first two-thirds of the film are the disillusioned Diane Selwyn's dream-fantasy of what her life might have been as the fresh and talented Betty. There is truth in both extremes: Lynch is playing with the audience, and he is portraying Los Angeles as a land of dreamers. But his film will never be forced into coherence, and it can't be entirely dismissed. I think it is some kind of great film -- the Sight & Sound critics poll in 2010 ranked it at No. 28 in the list of greatest films of all time -- but I also think it's self-indulgent and something of a dead end when it comes to narrative filmmaking. It has moments of sheer brilliance, including a performance by Watts that is superb, but they are moments in a somewhat annoying whole.

Sunday, January 29, 2017

A Serious Man (Joel Coen and Ethan Coen, 2009)

|

| Michael Stuhlbarg in A Serious Man |

Uncle Arthur: Richard Kind

Sy Abelman: Fred Melamed

Judith Gopnik: Sari Lennick

Danny Gopnik: Aaron Wolff

Sarah Gopnik: Jessica McManus

Rabbi Marshak: Alan Mandel

Don Milgram: Adam Arkin

Rabbi Nachtner: George Wyner

Mrs. Samsky: Amy Landecker

Director: Joel Coen, Ethan Coen

Screenplay: Joel Coen, Ethan Coen

Cinematography: Roger Deakins

Production design: Jess Gonchor

Music: Carter Burwell

Joel and Ethan Coen's A Serious Man is a mordant tragicomedy that was surprisingly nominated for a best picture Oscar, edging out films like A Single Man (Tom Ford), Julie & Julia (Nora Ephron), Bright Star (Jane Campion), Fantastic Mr. Fox (Wes Anderson), and my own preference, About Elly (Asghar Farhadi). Perhaps the Coen brothers were still coasting on the acclaim and the Oscars they received for No Country for Old Men (2007), but A Serious Man seems to me a decidedly lesser work, too dependent on comic Jewish stereotypes -- the pot-smoking kid studying for his bar mitzvah, the sister saving for a nose job, the feckless uncle who hogs the bathroom, and so on. The protagonist, Larry Gopnik, is a lesser, latter-day Job, whose "comforters" include some preoccupied, cliché-spouting rabbis whom Larry seeks out as he tries to deal with his troubles: His wife wants a divorce so she can marry a widowed family friend, Sy Abelman; his freeloading brother Arthur keeps getting in trouble with the police; his bid for tenure as a physics professor is threatened by a student -- a stereotyped Asian -- who tries to slip him an envelope full of cash so Larry will change his grade; a gentile neighbor seems to be displaying passive-aggressive hostility; a provocatively sexy neighbor sunbathes naked while Larry is on the roof trying to adjust the TV antenna, and so on. He is plagued with nightmares in which all of these figures combine to torment him. The Coens seem to regard all of this as a kind of parable: They begin the film with their version of a Jewish folktale involving a man, his wife, and a dybbuk, and they end it with an approaching tornado -- is God going to speak out of the whirlwind? But the result, especially given the setting in 1960s suburbia, feels more like imitation Philip Roth. There's a lot to admire in the film, including Roger Deakins's cinematography, and some of the theological issues it raises are worth raising, but it left me with a sour feeling.

Saturday, January 28, 2017

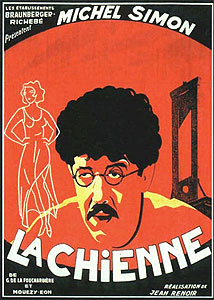

La Chienne (Jean Renoir, 1931)

Seeing Michel Simon as the milquetoast Maurice Legrand in La Chienne after L'Atalante (Jean Vigo, 1934) and Boudu Saved From Drowning (Jean Renoir, 1932) is something of a revelation, even if at the end of La Chienne he has become something like Boudu. But the entire film is a revelation: The second sound film by Renoir, it demonstrates an innovative mastery of what was essentially a new medium, one that even the Americans who claimed to have invented synchronized sound were still struggling with. Renoir -- with the help of sound technicians Denise Batcheff and Marcel Courmes -- creates an auditory ambience still rare in 1931, relying on dialogue and sound effects created on set and not in post-production. The most often-cited example is the rasp of the paper knife held by Lulu (Janie Marèse) as she cuts the pages of the book she's trying to read -- just before Legrand kills her with it. But the film is full of small auditory details like the squeaking of the shoes worn by the defense attorney (Sylvain Itkine) as he paces nervously back and forth before his doomed client, Dédé (Georges Flamant). But beyond the technical mastery, which also includes some brilliant camerawork by cinematographer Theodor Sparkuhl, the film is a tour de force of bitter irony, not least because Renoir keeps it from falling into sensationalism or unrelieved darkness. Legrand, initially the henpecked husband to a termagant (Magdeleine Bérubet), brings calamity to several lives, not only those of Lulu and Dédé, but also those of his wife and her supposedly dead ex-husband (Roger Gaillard). And yet, at the film's end he survives, not only unbroken but in many ways a stronger man than he was at the film's beginning. His story is framed as a puppet show with, as a puppet claims, "no moral message." But though Legrand commits fraud, adultery, and murder without receiving the official punishment of the law, the moral is aimed at those who scorned and abused him: Beware the worm who may turn and prove to be a viper.

Friday, January 27, 2017

Young and Innocent (Alfred Hitchcock, 1937)

If Alfred Hitchcock hadn't made The 39 Steps (1935) before Young and Innocent, the latter film might be taken for a somewhat less tightly plotted and certainly less well-cast sketch for the earlier one. Instead of Robert Donat as the man wrongly accused of murder on the run with Madeleine Carroll as his reluctant accomplice, we get the considerably lower-wattage Derrick De Marney and Nova Pilbeam. Young and Innocent (released in America as The Girl Was Young) feels almost like a retread, in which Hitchcock is trying out a few things that he'll use with more finesse in later films but isn't concerned with much in the way of plausibility and motivation. There is, for example, the focus on the hands when Erica Burgoyne (Pilbeam) is trapped in a car that's sliding into a sinkhole, and Robert Tisdall (De Marney) reaches out to grasp her. We'll see it again with variations in Saboteur (1942) and North by Northwest (1959), but there with more integration into the plot; here the sinking car seems to be only a gimmick introduced to allow Hitchcock to play with suspense-building techniques. There's also a long tracking crane shot that gradually focuses in on the villain (George Curzon) with a give-away tic that anticipates the tracking shot in Notorious (1946) that ends up on the key in Ingrid Bergman's hand. Hitchcock also uses Young and Innocent to exploit his well-known fear of the police, this time by mocking them, as when two cops are forced to hitch a ride with a farmer hauling livestock in his cart: When they complain about how crowded the cart is, the farmer tells them it was only built for ten pigs. Otherwise, Young and Innocent is agreeably nonchalant about plot essentials: Why was Tisdall mentioned in the murdered woman's will? Why did everyone assume that when he ran for help after discovering her body he was actually fleeing the scene of the crime? Why does he flee from the courtroom instead of sticking around to plead his case? Why does Erica so swiftly believe in his innocence? The film is nonsense, but it's enjoyable nonsense if you turn off such questions and go along for the ride. The screenplay, loosely based on a novel by Josephine Tey, is credited to Charles Bennett, Edwin Greenwood, and Anthony Armstrong, but I suspect it was much reworked by Hitchcock and his wife, Alma Reville, who is credited with "continuity," to allow for the director's experiments in suspense.

Thursday, January 26, 2017

Talk to Her (Pedro Almodóvar, 2002)

|

| Javier C'amara, Leonor Watling, Rosario Flores, and Dario Grandinetti in Talk to Her |

Wednesday, January 25, 2017

Umberto D. (Vittorio De Sica, 1952)

Umberto D. is sometimes grouped with Shoeshine (Vittorio De Sica, 1946) and Bicycle Thieves (De Sica, 1948) as the completing element in a trilogy about the underclass in postwar Rome. Shoeshine could be said to be a film about youth, Bicycle Thieves about middle age, and Umberto D. about old age. All three were directed by De Sica from screenplays by Cesare Zavattini that earned the writer Oscar nominations. Although Umberto D. is unquestionably a great film, it also seems to me the weakest of the three, largely because De Sica and Zavattini can't fully avoid the trap of sentimentality in telling a story about an old man and his dog. Umberto D. also relies too heavily on its score by Alessandro Cicognini to tug on our heartstrings. These flaws are mostly redeemed by the great sincerity of the performances, particularly by Carlo Battisti as Umberto, but also by Maria Pia Casilio as the pregnant housemaid, and Lina Gennari as Umberto's greedy landlady. Battisti, a linguistics professor who never acted before or after this film, is the perfect embodiment of the crusty Umberto Domenico Ferrari, a retired civil servant living on a pension that's inadequate to his needs. We're told that he has "debts," which include back rent to the landlady. He has no family except his dog, a small terrier called Flike, whom he dotes on, and no friends except for the housemaid, whose plight, since she's pregnant by one of two soldiers who have no intention of marrying her, is not much better than his. The film is most alive when it follows these characters on their daily rounds: the maid getting up in the morning and starting her daily chores, which include a continuing battle against the ants that infect the flat, and Umberto walking Flike, encountering old friends who carefully avoid noticing his plight or helping him out of it. He's too proud to beg and unwilling to go into a shelter because he would have to abandon Flike. In the end, he is forced out of the flat by the landlady, and wanders into a park where he tries to give Flike away to a little girl who has played with him there before. Her nursemaid, however, refuses to consider it -- dogs are dirty, she says. In a desperate moment, he picks up Flike, ready to stand in front of an oncoming train and die with him on the railroad tracks, but the dog panics, squirms out of his arms, and runs away. The film concludes with Umberto, having regained Flike's confidence, playing with the dog, their future still uncertain. The inconclusiveness of the final scene helps reduce the sentimentality that has flooded the sequence and focus our attention on Umberto's plight, rather than gratify our desire for closure.

Tuesday, January 24, 2017

Woman in the Moon (Fritz Lang, 1929)

Classic space-travel science fiction, Woman in the Moon was hugely influential on movies up until the time when human beings actually began to travel into space. You can find its traces in everything from the Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers serials to Destination Moon (Irving Pichel, 1950) and Forbidden Planet (Fred M. Wilcox, 1956), and even into the space age in TV series like Lost in Space (1965-68) and the first Star Trek series (1965-69). None of this should be surprising: Willy Ley, a German rocket scientist who was a technical adviser on Fritz Lang's film, came to the United States in 1935 and became an ardent popularizer of space travel and consultant to many science fiction writers and film directors. Actual space travel made some of Woman in the Moon obsolete: the notion that the moon has a breathable atmosphere and a temperate climate, for example. But Lang and his wife, Thea von Harbou, also consulted with another rocket scientist, Hermann Oberth, while writing the screenplay, and got a few things exactly and presciently right, like multistage rocketry, the need for zero-gravity restraints, and the firing of retro-rockets to slow the descent of the ship to the moon's surface. But perhaps their most influential contribution is the suspenseful (and often hokey) melodrama of the plot. They invented the familiar clichés: the discredited scientist whose theories turn out to be right; corporate villainy and greed at odds with the idealism of the scientists; the romantic triangle heightened by the isolation of the spaceship; the unexpected but useful stowaway; the need to sacrifice a member of the crew to return to safety. Fortunately, Lang never lets things bog down in the nascent clichés, and he has a capable cast to work with. Willy Fritsch is Wolf Helius, an idealistic rocketeer who has planned the space flight with the help of the discredited professor, Georg Manfeldt (Klaus Pohl). Gustav von Wangenheim and Gerda Maurus are Helius's assistants, Hans Windegger and Friede Velten, who have just gotten engaged, to the dismay of Helius, who is in love with Friede. Fritz Rasp is the evil mastermind Walter Turner, who threatens to destroy the rocket unless Helius allows him to come along on the voyage to advance the interests of the greedy corporate types who want to get their hands on the gold deposits that Manfeldt has theorized are plentiful on the moon. (With his hair slicked back across one side of his forehead, Rasp has a surprising resemblance to Adolf Hitler in this movie.) And the stowaway is Gustav (Gustl Gstettenbaur), a boy obsessed with space travel who brings his collection of sci-fi pulp magazines along with him. Even today, Woman in the Moon is good, larky fun.

Der müde Tod (Fritz Lang, 1921)

|

| Death (Bernhard Goetzke) and the Young Woman (Lil Dagover) in Der müde Tod |

Monday, January 23, 2017

The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (Andrew Dominik, 2007)

Both the title and the film are overlong, but it's hard to see how either of them could have been trimmed. The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford is a lingering, subtle meditation on the nature of celebrity set in an era long before the arrival of social media thrust celebrities like Donald Trump into our daily lives. Brad Pitt and Casey Affleck give memorable performances in their respective title roles -- Affleck received a supporting actor Oscar nomination, although his role is surely larger than Pitt's -- and they're well supported by Sam Shepard as Frank James, Mary-Louise Parker in the thankless role of Jesse's wife, Sam Rockwell as Robert Ford's brother Charley, and Jeremy Renner, Garret Dillahunt, and Paul Schneider as various ill-fated members of the James gang. There's also a cameo by former Bill Clinton adviser James Carville as the governor of Missouri who precipitates the assassination. It was only the second feature directed by New Zealander Andrew Dominik, who wrote the screenplay based on a novel by Ron Hansen. There's a bit too much lyric profundity in the screenplay, as in the voiceover by the narrator (Hugh Ross), who tells us about Jesse James: "Rooms seemed hotter when he was in them. Rains fell straighter. Clocks slowed. Sounds were amplified." That's a hard description for any actor to live up to, but Pitt does a good job of it in perhaps the best performance of his career. Since the title pretty much gives the plot away, the film wisely concentrates on exploring the characters of James and Ford, who meet when the latter joins the James gang for a train robbery in Blue Cut, Missouri. Ford has worshiped James since boyhood, and in one splendid scene James taunts and teases him into revealing the depths of his infatuation. Ford has memorized everything that could possibly link him to James: They both have brothers whose names contain six letters, for example. This is homoerotic hero-worship at its most intense -- and eventually, most deadly. The movie was filmed in Canada, with superb, Oscar-nominated cinematography by Roger Deakins. The score is by Nick Cave and Warren Ellis, and Cave himself plays the saloon singer who taunts Ford with "The Ballad of Jesse James," which refers to "the dirty little coward who shot Mr. Howard" (James's pseudonym).

Sunday, January 22, 2017

Bad Education (Pedro Almodóvar, 2004)

In the middle of Pedro Almodóvar's Bad Education, two men go into a theater that's holding a film noir festival. When they come out later, one says, "I kept having the feeling those films were about us." Indeed, if Almodóvar's movie is inspired by anything, it's film noir, but filtered through the Technicolor movies made by Alfred Hitchcock in the 1950s. The score by Alberto Iglesias often echoes the melancholy longing of Bernard Herrmann's music for Vertigo (Hitchcock, 1958). The intricate plot for Bad Education begins when a young man (Gael García Bernal) comes to the offices of film director Enrique Goded (Fele Martínez) and identifies himself as Goded's old school friend Ignacio Rodriguez. He doesn't call himself Ignacio anymore, he says. Instead, he goes by his stage name, Ángel Andrade, and he's hoping that Goded will cast him in his next film. Goded is more than surprised to see his old schoolmate -- in fact, he tells his assistant and current lover, Martín (Juan Fernández), Ignacio was his first love -- but he's currently experiencing a creative block and isn't hiring anyone now. So the actor leaves Goded a manuscript of a story he has written. Part of it, he says, is about their school days, and the rest is fiction based on what he thinks might have happened when they grew up. Goded reads the manuscript and is so impressed by the story it tells that he is determined to film it. And so begins an intricate film about memory, imagination, deception, betrayal, obsession, and revenge that centers on a pedophile priest's molestation of his young students. Bad Education was originally given an NC-17 rating by the Motion Picture Association of America for "explicit sexual content," but I suspect it was mostly because the sexual content involves two men. The rating was eventually reduced to R. The performance by García Bernal is spectacular: He manages several identities while retaining the core essential to all of them. Like most Almodóvar films, Bad Education is alive with bright primary colors -- the cinematography is by José Luis Alcaine, the art direction by Antxón Gómez, and the set decoration by Pilar Revuelta, with costumes designed by Paco Delgado and Jean-Paul Gaultier -- but the brightness only serves to heighten the shadows.

Saturday, January 21, 2017

The Gay Divorcee (Mark Sandrich, 1934)

Obviously, The Gay Divorcee wouldn't pass muster as the title for a heterosexual romantic comedy today, but the film's producers had to jump a few hurdles even in 1934, when the Hays Office censors were about to yield to the much stricter Production Code. The title of the Broadway musical on which the movie was based was Gay Divorce, and Catholic censors were strictly opposed to the idea that divorce could be anything other than a sin. However, assuming that she'd done her penance, a divorcee could be gay (in the older sense), just as Franz Lehár's old operetta asserted that a widow could be merry. This was the first teaming of Fred Astaire with Ginger Rogers in which they were the stars: They had been supporting players in their previous film, Flying Down to Rio (Thornton Freeland and George Nicholls Jr., 1933), and their dance numbers had caused such a sensation that RKO was eager to craft a musical around them. Pandro S. Berman, head of production at the studio, purchased the rights to Gay Divorce, in which Astaire had been the star on Broadway, and put a team of writers to work revising the musical's book by Dwight Taylor. The Broadway version had a score by Cole Porter, but all but one of the songs were jettisoned for the film. That song was the best, however: "Night and Day," which gave the stars their first great fall-in-love pas de deux. The screenplay, by many studio hands, takes the farcical premise of the play: Mimi Glossop (Rogers), seeks a divorce from her husand, and since they're in England, where the only justification for divorce is adultery, she, with the help of her Aunt Hortense (Alice Brady) and the lawyer Egbert Fitzgerald (Edward Everett Horton), arranges to be caught in a hotel room with a professional co-respondent, Rodolfo Tonetti (Erik Rhodes, who also played the role on Broadway). Meanwhile, however, she has fallen in love with Guy Holden (Astaire), an American she has just met -- and, of course, met cute. Through a sequence of screwball accidents, she winds up thinking that he's the co-respondent, and is disgusted that he should have such a sordid job. Eventually, everything is sorted out with the help of a hotel waiter (Eric Blore, also from the Broadway cast). In the middle of everything, there's a 20-minute-long production number centered on the film's big song, "The Continental," for which composer Con Conrad and lyricist Herb Magidson won the first Oscar ever given for a song written for a movie. The Gay Divorcee would rank with the best Astaire-Rogers films if it had a better score. Aside from "Night and Day," the rest are mostly forgettable novelty numbers, like "Let's K-nock K-nees," which is performed by a then-unknown Betty Grable with Horton and a gang of chorus members. Still, the movie lifted my spirits on Inauguration Night the way it must have soothed people's feelings during the Depression.

Friday, January 20, 2017

The Lives of Others (Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck, 2006)

Amid the almost universal acclaim, including a best foreign-language film Oscar, for Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck's The Lives of Others, there were some complaints from residents of the former East Germany that the writer-director was not as hard on his Stasi snoop, Gerd Wiesler (Ulrich Mühe), as he should have been. This is my second viewing of the film -- I saw it when it first appeared on DVD -- and I tend to agree. The movie as a whole is chilling -- well-plotted and well-acted -- but I'm not entirely convinced this time around by Wiesler's change of heart regarding the people he's surveiling: the playwright Georg Dreyman (Sebastian Koch) and his lover, the actress Christa-Marie Sieland (Martina Gedeck). At the start of the film, when we first see Wiesler teaching a class to Stasi-spy hopefuls, he's the perfect cold gray participant in a monstrous system of internal domestic espionage. But later, as he learns not only that the motive for spying on Dreyman and Sieland is not merely political but also sexual -- the minister of culture, Bruno Hempf (Thomas Theime) wants Dreyman eliminated so he can have Sieland all to himself -- he begins to be disillusioned with his work. And after a friend of Dreyman's, the blacklisted theater director Albert Jerska (Volkmar Kleinert), commits suicide and Dreyman sits down at the piano to play a piece of music -- composed for the film by Gabriel Yared -- called Sonata for a Good Man that Jerska had given him, Wiesler betrays the first real emotion we see from him in the film: A tear rolls down his cold gray face. Donnersmarck has said that he was inspired by Lenin's statement -- referred to in one point in the film -- that he had to give up listening to music like Beethoven's "Appassionata" sonata because it humanized him, distracting him from the task of revolution. On the other hand, we have all heard the stories of Nazi concentration camp commandants who read Schiller and Goethe and listened to Mozart and Schubert and were never deterred from their horrendous work by it. The flaw in Donnersmarck's film, I think, is that despite Mühe's brilliant performance as Wiesler, we never get enough of his backstory to suggest why he should be suddenly so vulnerable to sentiment. How could he have risen in the ranks of the Stasi to the point that he became not only a trusted agent but also an instructor of future agents if he has this key weakness? On the other hand, it's not a crippling flaw, thanks to exceptional performances and well-handled suspense.

Thursday, January 19, 2017

The Ascent (Larisa Shepitko, 1977)

|

| Boris Plotnikov in The Ascent |

Wednesday, January 18, 2017

The Last Métro (François Truffaut, 1980)

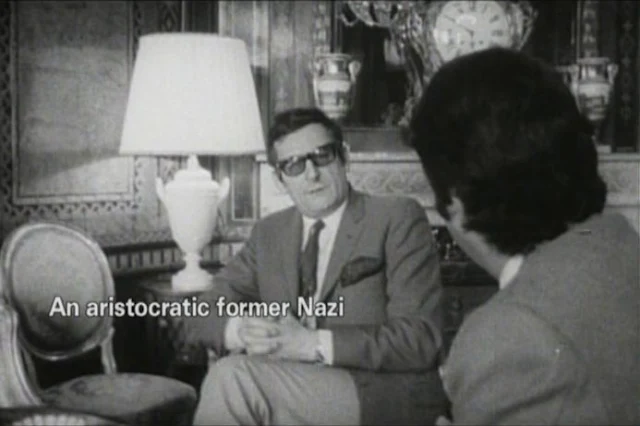

Watching The Last Métro only a day after The Sorrow and the Pity (Marcel Ophüls, 1969) was instructive, if a little bit unfair to François Truffaut's romantic backstage drama. The two films deal with the same milieu, France during World War II, but with such differing approaches that the stark devotion to ferreting out the truth in Ophüls's film makes Truffaut's dramatization of the plight of a Jewish theater owner and his company feel more glossy and sentimental than it perhaps really is. Truffaut, who was born in 1932, was only a boy during the war, so he can't be expected to have the kind of first-hand awareness of events that the adults pictured in his film possess. Consequently, his own preoccupation, the world of actors and directors, takes precedence in the film over the suffering people endured under the Nazis. He has admitted in interviews that The Last Métro is a kind of companion film to Day for Night (1973), his behind-the-camera account of making a movie. What he does recall is the theater -- in his case the movie theater rather than the legitimate stage -- was a kind of refuge from hardship, the hunger and cold brought about by wartime rationing. People gathered in theaters for communal warmth. The story is principally about an actress, Marion Steiner (Catherine Deneuve), who is trying to keep the theater that was run before the war by her husband, Lucas (Heinz Bennent), open. Lucas, who is Jewish, is rumored to have fled to America, but in fact he is hiding in the cellar of the theater while Marion, with the help of the rest of the regular company, stages a play. The director, Jean-Loup Cottins (Jean Poiret), is working from the notes Lucas made on the play before his disappearance. Cottins has his own dangerous secret: He's gay. A new leading man, Bernard Granger (Gérard Depardieu), joins the company, and inevitably a tension develops between him and Marion. Meanwhile, Lucas has figured out ways to listen in on rehearsals and make suggestions to Marion that she passes along to Cottins, who is unaware of Lucas's hiding place. Marion also has the difficulty of dealing with the authorities, who could close the theater at any moment, especially when the influential critic Daxiat (Jean-Louis Richard), a collaborator with the Nazis, takes an interest in her and the play. What takes place on stage, namely the sexual tension between the characters played by Marion and Bernard, often mirrors what's happening backstage. The Last Métro is a well-crafted movie -- Truffaut wrote the screenplay with Suzanne Schiffman -- that was France's entry for the best foreign-film Oscar and won a raft of the French César Awards, including one for cinematographer Nestor Almendros.

The Sorrow and the Pity (Marcel Ophuls, 1969)

|

| Christian de la Mazière, one of those interviewed in The Sorrow and the Pity |

Tuesday, January 17, 2017

Battleship Potemkin (Sergei Eisenstein, 1925)

A perennial on "best films in history" lists, Battleship Potemkin is certainly one of the best-crafted movies ever. No matter how hokey and manipulative it seemed, I sat enthralled through my most recent viewing as the pounding, throbbing endless crescendo of music and editing surged toward the political victory of the Potemkin over the Czar's fleet. (The music on this version was Edmund Meisel's, which was performed at the Berlin premiere in 1926.) Because of the celebrated "Odessa Steps" sequence, which is cited in every textbook on editing and montage and in every tribute to Sergei Eisenstein or documentary about propaganda, I had forgotten that the real climax of the film is its final sequence. I had also forgotten how truly epic the film feels, with the great massing of crowds before the massacre on the steps. But is it a great film? Not if you're judging a film by any standard other than the way it gets blood pumping. It lacks insight into any human emotion other than resentment and the herd instinct. It's a masterpiece of propaganda. As with other such masterpieces, such as Leni Riefensthal's Triumph of the Will (1935), it lies to us. Which is all right, as long as we know it's lying and can keep our eye on the truth.

Joy (David O. Russell, 2015)

A thoroughly conventional movie with an exceptional cast that features what seems to be the core of writer-director David O. Russell's stock company, Jennifer Lawrence and Bradley Cooper, Joy is the kind of feel-good underdog-against-the-odds movie with screwball touches that could have been made at almost any time in Hollywood history. I can easily imagine it in the 1940s with Rosalind Russell and Fred MacMurray, for example. Joy Mangano (Lawrence) was a brilliant student in high school, but she didn't go on to college, and now struggles to make ends meet, while dabbling with ideas for inventions. A divorcee, she lives in an unusual household: In addition to her two children and her grandmother (Diane Ladd), the ménage also includes Joy's mother (Virginia Madsen), who spends her days in bed watching soap operas, and Joy's ex-husband (Edgar Ramirez), who lives in the basement. Joy's father (Robert De Niro) also joins the household after splitting from his latest wife, but he soon takes up with Trudy, a wealthy widow (Isabella Rossellini). When Joy comes up with the idea for a self-wringing mop, Trudy agrees to help finance it. Joy has to contract the manufacture of some of the mop's parts, and she struggles to market it until the idea comes to sell it on TV. She approaches the QVC shopping channel, where an executive, Neil Walker (Cooper), takes an interest in the product. It becomes a big seller, but then the company Joy contracted to make the parts claims ownership of the design. Facing bankruptcy, Joy fights the claim, wins, and becomes a huge success, marketing other household products. There's a real-life Joy Mangano on whose story the film is based, with the usual disregard for accuracy. Lawrence got an Oscar nomination for her performance, which is, as always, wonderful. She gives the film more than it deserves, and the supporting cast measures up to her. But there are few surprises in the story or in Russell's treatment of it, unlike his previous films with Lawrence and Cooper, Silver Linings Playbook (2012) and American Hustle (2013).

Monday, January 16, 2017

The Antoine Doinel Cycle

The 400 Blows (François Truffaut, 1959)

Antoine Doinel: Jean-Pierre Léaud

Julien Doinel: Albert Rémy

Gilberte Doinel: Claire Maurier

René Bigey: Patrick Auffay

M. Bigey: Georges Flamant

Director: François Truffaut

Screenplay: François Truffaut, Marcel Moussy

Cinematography: Henri Decaë

Music: Jean Constantin

One of the unquestioned great movies, and one of the greatest feature-film directing debuts, The 400 Blows would still resonate with film-lovers even if François Truffaut hadn't gone on to create four sequels tracking the life and loves of his protagonist, Antoine Doinel (Jean-Pierre Léaud). There are, in fact, those who think that the last we should have seen of Antoine was the haunting freeze-frame at the end of the film. But Antoine continued to grow up on screen, and perhaps more remarkably, so did Léaud, carving out his own career after his debut as a 13-year-old. (It's hard to think of any American child actors who were able to maintain a film career into adulthood as well as Léaud did. Mickey Rooney? Dean Stockwell? Who else?) Having Truffaut as a mentor certainly helped, but Léaud had an unmistakable gift. He is on screen for virtually all of the 99-minute run time, and provides a gallery of memorable moments: Antoine in the amusement-park centrifuge, Antoine in the police lockup, Antoine on the run -- in cinematographer Henri Decaë's brilliant long tracking shot. And my personal favorite moment: when the psychologist asks Antoine if he's ever had sex. Léaud responds with a beautiful mixture of surprise, amusement, and embarrassment. It's so genuine a response that I have to think it was improvised, that Truffaut surprised Léaud with the question. But even so, Léaud never drops character in his response. This praise of Léaud is not to undervalue the magnificent supporting cast, or the haunting score by Jean Constantin. It's a film in which everything works.

Antoine and Colette (François Truffaut, 1962)

Antoine Doinel: Jean-Pierre Léaud

Colette: Marie-France Pisier

Colette's Mother: Rosy Varte

Colette's Stepfather: François Darbon

René: Patrick Auffay

Albert Tazzi: Jean-François Adam

Director: François Truffaut

Screenplay: François Truffaut

Cinematography: Raul Coutard

Music: Georges Delerue

Four years after he made The 400 Blows, Truffaut was asked to contribute to an anthology of short films by directors from various countries to be called Love at Twenty. As he had with the first film, Truffaut drew on his own experience, an infatuation with a girl he had met at the Cinémathèque Française. And since Léaud was available -- he had worked with Julien Duvivier on Boulevard (1960) after completing The 400 Blows -- it made sense for him to play Antoine Doinel again. A narrator tells us that Antoine had been sent to another reform school after escaping from the first, and that this time he had responded well to a psychologist: After leaving school, he has found a job working for the Phillips record company and is living on his own. Then he sees a pretty young woman at a concert of music by Berlioz and falls for her. Colette is not much interested in him, but she is evidently flattered by his advances. Her parents like Antoine and encourage him so much that he rents a room across the street from them. (Truffaut had done the same thing during his crush.) But one evening when he comes to dinner at their apartment, a man named Albert calls on Colette and she leaves Antoine watching TV with her parents. It's a droll little film, scarcely more than an anecdote, and the stable, lovestruck Antoine doesn't seem much like either the rebellious Antoine of the first film or the more scattered Antoine of the later ones in the cycle.

Stolen Kisses (François Truffaut, 1968)

Antoine Doinel: Jean-Pierre Léaud

Christine Darbon: Claude Jade

Georges Tabard: Michael Lonsdale

Fabienne Tabard: Delphine Seyrig

M. Blady: Michael Lonsdale

Mme. Darbon: Claire Duhamel

Lucien Darbon: Daniel Ceccaldi

Director: François Truffaut

Screenplay: François Truffaut, Claude de Givray, Bernard Revon

Cinematography: Denys Clerval

Music: Antoine Duhamel

The Antoine of Stolen Kisses is in his 20s, but has reverted to the more haphazard ways of his adolescence: He has been kicked out of the army, and now relies on a series of odd jobs to get by. But he has also renewed acquaintance with a young woman he met before going into the army, Christine Darbon. Like Colette's parents, hers are quite taken with Antoine, and they help him get a job as a night clerk in a hotel. He gets fired from that job after helping a private detective who is spying on an adulterous couple, but the detective helps Antoine get a job with his agency. While working for the detective agency, he has to pose as a clerk in a shoe store, and winds up in a liaison with the store owner's wife, Fabienne. When that ends badly, he becomes a TV repairman, which brings him back to Christine, with whom he winds up in bed after trying to fix her TV. At the film's end, a strange man who has been following Christine comes up to her and Antoine in the park and declares his love for her. She says he must be crazy, and Antoine, who perhaps recognizes his earlier infatuation with Colette in the man's obsession, murmurs, "He must be." Stolen Kisses is the loosest, funniest entry in the cycle, though it was made at a time when Truffaut was politically preoccupied: The film opens with a shot of the shuttered gates of the Cinémathèque Française, which was shut down in a conflict between its director, Henri Langlois, and culture minister André Malraux. This caused an uproar involving many of the directors of the French New Wave. Some of Antoine's anarchic approach to life may have been inspired by the rebelliousness toward the establishment prevalent in the film community. But it's clear that the idea of a cycle of Antoine Doinel films has been brewing in Truffaut's mind: There is a cameo appearance by Marie-France Pisier as Colette and Jean-François Adam as Albert, now married and the parents of an infant.

Bed and Board (François Truffaut, 1970)

Antoine Doinel: Jean-Pierre Léaud

Christine Darbon Doinel: Claude Jade

Mme. Darbon: Claire Duhamel

Lucien Darbon: Daniel Ceccaldi

Kyoko: Hiroko Berghauer

Director: François Truffaut

Screenplay: François Truffaut, Claude de Givray, Bernard Revon

Cinematography: Néstor Almendros

Music: Antoine Duhamel

Antoine and Christine have married, and they have settled down in a small apartment. (There's some indication that it's paid for by her parents.) She gives violin lessons and he sells flowers -- carnations, which he dyes, using some environmentally questionable potions. But settling down isn't in Antoine's nature, and when Christine gets pregnant he looks for more lucrative work. He finds a curious sinecure in a company run by an American: Antoine maneuvers model ships by remote control through a mockup of a harbor. ("It gives me time to think," he says.) One day, a Japanese businessman comes to see the demonstration, accompanied by a pretty translator named Kyoko (Hiroko Berghauer), and Antoine is soon involved in an affair with her. Naturally, this precipitates a breakup, though by film's end they have seemingly reconciled. Still, it's obvious that the marriage is not destined to be permanent. They can't even agree on a name for their son: She wants him to be called Ghislain, and he wants to call him Alphonse. Antoine wins out by a trick: He's the one who goes to the registry office to legalize the boy's name. Antoine also spends time writing a novel about his boyhood, to which Christine objects: "I don't like this business of writing about your childhood, dragging your parents through the mud. I don't know much but I do know one thing: If you use art to settle accounts, it's no longer art." Truffaut had his own regrets about the portrait of his parents in The 400 Blows. Less farcical than Stolen Kisses, Bed and Board still has a strong vein of comedy tinged with melancholy.

Love on the Run (François Truffaut, 1979)

Antoine Doinel: Jean-Pierre Léaud

Colette Tazzi: Marie-France Pisier

Christine Doinel: Claude Jade

Liliane: Dani

Sabine Barnerias: Dorothée

Xavier Barnerias: Daniel Mesguich

M. Lucien: Julien Bertheau

Director: François Truffaut

Screenplay: François Truffaut, Marie-France Pisier, Jean Aurel, Suzanne Schiffman

Cinematography: Néstor Almendros

Music: Georges Delerue

Truffaut admitted that he wasn't happy with the final film in the cycle. It's a bit too heavily reliant on flashback clips from the four earlier films, and if it's intended to show that Antoine has finally stabilized now that he's in his 30s and divorced from Christine, it doesn't quite make the case. He has a new girlfriend, Sabine, his novel has been published several years earlier, and he works as a proofreader for a printing house. He's on friendly terms with Christine, and agrees to take their son, Alphonse, to the train station when the boy leaves for a summer music camp. At the station, he runs into Colette, now a defense lawyer, who is on her way to confer with a client -- a man who has murdered his 3-year-old boy. Perhaps a little too coincidentally, Colette is involved with Sabine's brother, Xavier, and having encountered Antoine before, she has bought a copy of his novel to read on the train. Antoine impulsively boards the train, and sets up a meeting with Colette in the dining car, after which she invites him back to her compartment. All of this sets up a series of revelations: Colette's marriage to Albert broke up after their small daughter was killed by a car. She claims that she supplements her small income as a lawyer by prostituting herself with men she meets on trains. Antoine finally made peace with his mother after her death when he met her old lover, M. Lucien, who persuaded him to visit his mother's grave. (There is a flashback to the scene in The 400 Blows when Antoine, playing hooky, sees his mother kissing a strange man on the street.) Antoine became infatuated with Sabine after hearing a man in a phone booth arguing with a woman on the other end of the line and then tearing up her photograph. Antoine picked up the pieces from the floor, put them together, and after some sleuthing, discovered the woman was Sabine. His marriage to Christine finally broke up after he slept with her friend Liliane, who he previously had thought was having a lesbian relationship with Christine. And so on. The result of all the flashbacks and revelations is not to round out the Antoine Doinel saga, but to make Love on the Run feel over-contrived. Marie-France Pisier, incidentally, contributed to the screenplay, which is mostly by Truffaut.

|

| Jean-Pierre Léaud in The 400 Blows |

Julien Doinel: Albert Rémy

Gilberte Doinel: Claire Maurier

René Bigey: Patrick Auffay

M. Bigey: Georges Flamant

Director: François Truffaut

Screenplay: François Truffaut, Marcel Moussy

Cinematography: Henri Decaë

Music: Jean Constantin

One of the unquestioned great movies, and one of the greatest feature-film directing debuts, The 400 Blows would still resonate with film-lovers even if François Truffaut hadn't gone on to create four sequels tracking the life and loves of his protagonist, Antoine Doinel (Jean-Pierre Léaud). There are, in fact, those who think that the last we should have seen of Antoine was the haunting freeze-frame at the end of the film. But Antoine continued to grow up on screen, and perhaps more remarkably, so did Léaud, carving out his own career after his debut as a 13-year-old. (It's hard to think of any American child actors who were able to maintain a film career into adulthood as well as Léaud did. Mickey Rooney? Dean Stockwell? Who else?) Having Truffaut as a mentor certainly helped, but Léaud had an unmistakable gift. He is on screen for virtually all of the 99-minute run time, and provides a gallery of memorable moments: Antoine in the amusement-park centrifuge, Antoine in the police lockup, Antoine on the run -- in cinematographer Henri Decaë's brilliant long tracking shot. And my personal favorite moment: when the psychologist asks Antoine if he's ever had sex. Léaud responds with a beautiful mixture of surprise, amusement, and embarrassment. It's so genuine a response that I have to think it was improvised, that Truffaut surprised Léaud with the question. But even so, Léaud never drops character in his response. This praise of Léaud is not to undervalue the magnificent supporting cast, or the haunting score by Jean Constantin. It's a film in which everything works.

Antoine and Colette (François Truffaut, 1962)

|

| Jean-Pierre Léaud and Marie-France Pisier in Antoine and Colette |

Colette: Marie-France Pisier

Colette's Mother: Rosy Varte

Colette's Stepfather: François Darbon

René: Patrick Auffay

Albert Tazzi: Jean-François Adam

Director: François Truffaut

Screenplay: François Truffaut

Cinematography: Raul Coutard

Music: Georges Delerue

Four years after he made The 400 Blows, Truffaut was asked to contribute to an anthology of short films by directors from various countries to be called Love at Twenty. As he had with the first film, Truffaut drew on his own experience, an infatuation with a girl he had met at the Cinémathèque Française. And since Léaud was available -- he had worked with Julien Duvivier on Boulevard (1960) after completing The 400 Blows -- it made sense for him to play Antoine Doinel again. A narrator tells us that Antoine had been sent to another reform school after escaping from the first, and that this time he had responded well to a psychologist: After leaving school, he has found a job working for the Phillips record company and is living on his own. Then he sees a pretty young woman at a concert of music by Berlioz and falls for her. Colette is not much interested in him, but she is evidently flattered by his advances. Her parents like Antoine and encourage him so much that he rents a room across the street from them. (Truffaut had done the same thing during his crush.) But one evening when he comes to dinner at their apartment, a man named Albert calls on Colette and she leaves Antoine watching TV with her parents. It's a droll little film, scarcely more than an anecdote, and the stable, lovestruck Antoine doesn't seem much like either the rebellious Antoine of the first film or the more scattered Antoine of the later ones in the cycle.

Stolen Kisses (François Truffaut, 1968)

|

| Jean-Pierre Léaud in Stolen Kisses |

Christine Darbon: Claude Jade

Georges Tabard: Michael Lonsdale

Fabienne Tabard: Delphine Seyrig

M. Blady: Michael Lonsdale

Mme. Darbon: Claire Duhamel

Lucien Darbon: Daniel Ceccaldi

Director: François Truffaut

Screenplay: François Truffaut, Claude de Givray, Bernard Revon

Cinematography: Denys Clerval

Music: Antoine Duhamel

Bed and Board (François Truffaut, 1970)

|

| Claude Jade and Jean-Pierre Léaud in Bed and Board |

Christine Darbon Doinel: Claude Jade

Mme. Darbon: Claire Duhamel

Lucien Darbon: Daniel Ceccaldi

Kyoko: Hiroko Berghauer

Director: François Truffaut

Screenplay: François Truffaut, Claude de Givray, Bernard Revon

Cinematography: Néstor Almendros

Music: Antoine Duhamel

Antoine and Christine have married, and they have settled down in a small apartment. (There's some indication that it's paid for by her parents.) She gives violin lessons and he sells flowers -- carnations, which he dyes, using some environmentally questionable potions. But settling down isn't in Antoine's nature, and when Christine gets pregnant he looks for more lucrative work. He finds a curious sinecure in a company run by an American: Antoine maneuvers model ships by remote control through a mockup of a harbor. ("It gives me time to think," he says.) One day, a Japanese businessman comes to see the demonstration, accompanied by a pretty translator named Kyoko (Hiroko Berghauer), and Antoine is soon involved in an affair with her. Naturally, this precipitates a breakup, though by film's end they have seemingly reconciled. Still, it's obvious that the marriage is not destined to be permanent. They can't even agree on a name for their son: She wants him to be called Ghislain, and he wants to call him Alphonse. Antoine wins out by a trick: He's the one who goes to the registry office to legalize the boy's name. Antoine also spends time writing a novel about his boyhood, to which Christine objects: "I don't like this business of writing about your childhood, dragging your parents through the mud. I don't know much but I do know one thing: If you use art to settle accounts, it's no longer art." Truffaut had his own regrets about the portrait of his parents in The 400 Blows. Less farcical than Stolen Kisses, Bed and Board still has a strong vein of comedy tinged with melancholy.

Love on the Run (François Truffaut, 1979)

|

| Claude Jade and Jean-Pierre Léaud in Love on the Run |

Colette Tazzi: Marie-France Pisier

Christine Doinel: Claude Jade

Liliane: Dani

Sabine Barnerias: Dorothée

Xavier Barnerias: Daniel Mesguich

M. Lucien: Julien Bertheau

Director: François Truffaut

Screenplay: François Truffaut, Marie-France Pisier, Jean Aurel, Suzanne Schiffman

Cinematography: Néstor Almendros

Music: Georges Delerue

Truffaut admitted that he wasn't happy with the final film in the cycle. It's a bit too heavily reliant on flashback clips from the four earlier films, and if it's intended to show that Antoine has finally stabilized now that he's in his 30s and divorced from Christine, it doesn't quite make the case. He has a new girlfriend, Sabine, his novel has been published several years earlier, and he works as a proofreader for a printing house. He's on friendly terms with Christine, and agrees to take their son, Alphonse, to the train station when the boy leaves for a summer music camp. At the station, he runs into Colette, now a defense lawyer, who is on her way to confer with a client -- a man who has murdered his 3-year-old boy. Perhaps a little too coincidentally, Colette is involved with Sabine's brother, Xavier, and having encountered Antoine before, she has bought a copy of his novel to read on the train. Antoine impulsively boards the train, and sets up a meeting with Colette in the dining car, after which she invites him back to her compartment. All of this sets up a series of revelations: Colette's marriage to Albert broke up after their small daughter was killed by a car. She claims that she supplements her small income as a lawyer by prostituting herself with men she meets on trains. Antoine finally made peace with his mother after her death when he met her old lover, M. Lucien, who persuaded him to visit his mother's grave. (There is a flashback to the scene in The 400 Blows when Antoine, playing hooky, sees his mother kissing a strange man on the street.) Antoine became infatuated with Sabine after hearing a man in a phone booth arguing with a woman on the other end of the line and then tearing up her photograph. Antoine picked up the pieces from the floor, put them together, and after some sleuthing, discovered the woman was Sabine. His marriage to Christine finally broke up after he slept with her friend Liliane, who he previously had thought was having a lesbian relationship with Christine. And so on. The result of all the flashbacks and revelations is not to round out the Antoine Doinel saga, but to make Love on the Run feel over-contrived. Marie-France Pisier, incidentally, contributed to the screenplay, which is mostly by Truffaut.

Sunday, January 15, 2017

Blood Simple (Joel Coen and Ethan Coen, 1984)

So many of the Coen brothers' best films, like Miller's Crossing (1990), Fargo (1996), and No Country for Old Men (2007), are about plans that backfire, that it's no surprise their first feature, Blood Simple, has a plot that hinges on just that. When Texas bar owner Julian Marty (Dan Hedaya) discovers that his wife, Abby (Frances McDormand), is having an affair with one of his bartenders, Ray (John Getz), he hires a private detective, Visser (M. Emmet Walsh), who discovered the affair, to kill them. But Visser has other ideas: He finds Ray and Abby asleep in Ray's bed, takes a picture of them, and steals Abby's gun. Then he doctors the photograph to make it look like he has shot them to death, collects the reward from Marty, and then shoots Marty with Abby's gun to frame her for his murder. But wait, there's more! It involves the fact that Marty is not (yet) dead, that he kept a copy of the doctored photo in his safe when he paid off Visser, and that Visser accidentally left his cigarette lighter behind in Marty's office. And so on, as almost everyone gets what's coming to them. Blood Simple may be just a tad over-plotted, and there are a few things that seem too contrived -- Visser's carelessness with the lighter, for one. But on the whole, it's good nasty fun, with some solid performances. McDormand, in her first film role, is strikingly pretty, and manages a remarkable character transition from naïveté to resourcefulness. Walsh and Hedaya, two reliable character actors, make the most of their juicy roles. Cinematographer Barry Sonnenfeld and composer Carter Burwell, both making their feature film debuts, help craft the film's very effective noir atmosphere.

Saturday, January 14, 2017

The Ear (Karel Kachyna, 1970)

|

| Radoslav Brzobohaty and Jirina Bohdolová in The Ear |

Friday, January 13, 2017

World on a Wire (Rainer Werner Fassbinder, 1973)

What we call "reality" is, as we all know now, a construct, the product of the limitations of our senses. But what if we, too, are part of the construct, put here by some other entity and blinded to the reality that lies beyond the senses? That way lies religion -- "Now we see through a glass darkly...." -- and metaphysics -- now largely dismissed as "asking unanswerable questions" -- but also science fiction. Witness the popularity of a film like The Matrix (Lana Wachowski and Lilly Wachowski, 1999) and its sequels. In fact, Rainer Werner Fassbinder got there more than two decades before the Wachowskis. In 1973 he created a two-part television series, World on a Wire, that aired in Germany, and then became a kind of cult hit via file-sharing on the internet before being restored in 2010 and screened at the Berlin Film Festival. In it, a German research institute has created a simulated world in its supercomputer. The inhabitants of this world have been given consciousness, but only one of them has knowledge of the world outside the computer. He serves as a contact between the programmers and the simulated beings. But then the sudden death of the head of the program puts his second-in-command, Stiller (Klaus Löwitsch), in charge of investigating not only the death of his predecessor but also the suicide of one of the simulated beings. Stranger and stranger things begin to happen, until Stiller learns that he is also a simulation in his own simulated world. He also learns that the institute's simulated world is being used for commercial purposes, something that violates its agreement with the government funding it. As he comes to terms with this knowledge, his increasingly erratic behavior makes him a target for assassins, and his one hope is to find the contact with the level above that's simulating him. Got that? The head-spinning premise of the film comes from a novel, Simulacron-3, by the American writer Daniel F. Galouye, adapted by Fassbinder and Fritz Müller-Scherz. Fassbinder gives it a good deal of his characteristic style in the adaptation: The women in Stiller's world, for example, always wear cocktail dresses, even at work, and rooms are filled with mirrors to suggest the layers of reflected reality in the three levels. The costume designer is Gabriele Pillon and the production design is by Horst Giese, Walter Koch, and Kurt Raab. It was filmed in 16 mm for television, which means there's some graininess and focus problems in some parts of the restored film, but the cinematography is by Fassbinder's frequent collaborator Michael Ballhaus, along with Ulrich Prinz. Löwitsch is very good as Stiller, taking on kind of James Bondian role, and the paranoid atmosphere prevails even when the plot gets a bit snarled in its own premise.

Thursday, January 12, 2017

Two With Marcello Mastroianni

A Slightly Pregnant Man (Jacques Demy, 1973)

Irène de Fontenoy: Catherine Deneuve

Marco Mazetti: Marcello Mastroianni

Dr. Delavigne: Micheline Presle

Maria Mazetti: Marisa Pavan

Director: Jacques Demy

Screenplay: Jacques Demy

Cinematography: Andréas Winding

Production design: Bernard Evein

Music: Michel Legrand

A Special Day (Ettore Scola, 1977)

Antonietta: Sophia Loren

Gabriele: Marcello Mastroianni

Emanuele: John Vernon

Caretaker: Françoise Berd

Director: Ettore Scola

Screenplay: Ruggero Maccari, Ettore Scola, Maurizio Costanzo

Cinematography: Pasqualino De Santis

Production design: Luciano Ricceri

The great charm of Marcello Mastroianni lies, I think, in the fact that he always seems to be the odd man out. Despite his good looks and sex appeal, there is always the sense that the characters he plays, even though they attract women on the order of Catherine Deneuve and Sophia Loren, are never quite in charge of the world they inhabit. Certainly this is true of his most famous roles, Marcello in La Dolce Vita (Federico Fellini, 1960) and Guido in 8 1/2 (Fellini, 1963). And directors Jacques Demy and Ettore Scola exploit this otherness in Mastroianni in very different ways: Demy in the satiric A Slightly Pregnant Man and Scola in the earnest A Special Day. In the former film, whose French title was the lengthy L'Événement le plus important depuis que l'homme a marché sur la Lune (The Most Important Event Since Man Walked on the Moon), Mastroianni plays Marco, a driving-school instructor who feels out of sorts and goes to see a doctor who decides that he must be pregnant. When a well-known specialist confirms the diagnosis and presents his findings to other scientists, the press goes wild and the advertising department for a maternity-wear company launches a campaign for male maternity clothes. Marco winds up on posters everywhere, and he and his fiancée, Irène, begin to make big plans for the money the company pays him. Eventually, the diagnosis proves to be false, however, and the film concludes with an anticlimactic thud. Demy, whose best-known work is probably the cotton-candy musicals The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964) and The Young Girls of Rochefort (1967), seems to have launched into his screenplay with no sense of how to end it satisfactorily. Until that point, however, Mastroianni and Deneuve have fun with their roles. Forgoing her usual sophisticated chic, she plays a somewhat blowsy beauty-shop owner. A Special Day earned Mastroianni one of his three Oscar nominations, partly because there's nothing the Academy likes better than a straight actor daring to play gay. He is Gabriele, a radio announcer who has lost his job because the Fascists have begun purging the work force of "undesirables." The day is May 8, 1938, when Hitler visits Mussolini in Rome to solidify their alliance. He lives in a large apartment complex with windows facing an open courtyard. Across the way lives Antonietta, a woman with an abusive husband and six children. On this day, she has stayed home to clean house after sending her family off to the parades and speeches, but when the family's pet mynah bird escapes and flies out into the courtyard, she asks Gabriele's help in retrieving him. They are virtually the only people left in the complex other than the nosy, gossipy concierge, whose radio is blaring the news of the day -- Fascist anthems, speeches, the cheers of the crowd, and a running patriotic commentary -- which serves as the sometimes ironic counterpoint to the growing intimacy of the mismatched couple. A severely deglamourized Loren gives a fine performance, as does Mastroianni: Gabriele is aware that at any moment he may be taken away to a concentration camp, and he vacillates between suicide and a carpe diem fatalism. The film is a little too predictable, and although the screenplay by Scola and Ruggero Maccari is original, it feels somewhat like an adaptation of a two-character stage play. Pasqualino De Santis's cinematography, using long takes and tracking shots through the apartment complex (which we never leave except in the archival newsreel footage at the film's beginning), helps open it up.

|

| Catherine Deneuve and Marcello Mastroianni in A Slightly Pregnant Man |

Marco Mazetti: Marcello Mastroianni

Dr. Delavigne: Micheline Presle

Maria Mazetti: Marisa Pavan

Director: Jacques Demy

Screenplay: Jacques Demy

Cinematography: Andréas Winding

Production design: Bernard Evein

Music: Michel Legrand

A Special Day (Ettore Scola, 1977)

|

| Marcello Mastroianni and Sophia Loren in A Special Day |

Gabriele: Marcello Mastroianni

Emanuele: John Vernon

Caretaker: Françoise Berd

Director: Ettore Scola

Screenplay: Ruggero Maccari, Ettore Scola, Maurizio Costanzo

Cinematography: Pasqualino De Santis

Production design: Luciano Ricceri

Wednesday, January 11, 2017

The Great McGinty (Preston Sturges,1940)

|

| Poster with the British title for The Great McGinty |

Tuesday, January 10, 2017

Two by Jean Renoir

Boudu Saved From Drowning (Jean Renoir, 1932)

|

| Michel Simon in Boudu Saved From Drowning |

Édouard Lestingois: Charles Granval

Emma Lestingois: Marcelle Hainia

Chloë Anne Marie: Sévérine Lerczinska

Vigour: Jean Gehret

Godin: Max Dalban

A Student: Jean Dasté

Director: Jean Renoir

Screenplay: Jean Renoir, Albert Valentin

Based on a play by René Fauchois

Cinematography: Georges Asselin

A Day in the Country (Jean Renoir, 1936)

|

| Sylvia Bataille and Georges D'Arnoux in A Day in the Country |

Henri: Georges D'Arnoux

Madame Dufour: Jane Marken

Monsieur Dufour: André Gabriello

Rodolphe: Jacques B. Brunius

Anatole: Paul Temps

Grandmother: Gabrielle Fontan

Uncle Poulain: Jean Renoir

Waitress: Marguerite Renoir

Director: Jean Renoir

Screenplay: Jean Renoir

Based on a story by Guy de Maupassant

Cinematography: Claude Renoir

Music: Joseph Kosma

"Épater la bourgeoisie!" went the rallying cry of France's 19th-century poets like Baudelaire and Rimbaud, who styled themselves as "Decadents." But ever since Molière's M. Jourdain, the social-climbing bourgeois gentilhomme, was delighted to discover that he was speaking prose, French artists of whatever medium have delighted themselves in satirizing the manners and morals of the middle class, sometimes affectionately and sometimes savagely. On my living room wall I have two prints of cartoons done by Honoré Daumier in a series he called "Pastorales." Both show very solidly middle-class and middle-aged couples, presumably Parisians taking a day in the country. In one, the husband carries his large, copiously clad wife on his back as he fords a small stream that barely comes to his ankles. They have evidently been caught in a summer storm, for he is chiding her that such things are to be expected, even on the sunniest day. Meanwhile, she is urging him, "Ah, Jules, don't let the torrent sweep us away!" In the other, a similarly clad woman sits on the bank of a pond in which her husband, wearing his glasses and with his head wrapped in a handkerchief, has been taking a dip. "The water is delicious, Virginie," he says. "I assure you, you're making a mistake by not joining me." I was reminded of these prints while watching Jean Renoir's great short film -- it's only 40 minutes long, but every minute is golden -- A Day in the Country. In it, the Dufour family -- husband, wife, daughter, future son-in-law, and comically deaf grandmother -- find a country inn in a beautiful setting on their day away from the city. The mother and daughter immediately become targets for two young men, who manage to set off with them in their skiffs on the river, after diverting the other men by lending them fishing poles. The daughter, Henriette, goes with Henri. When a storm comes up, they take shelter in the woods, where she yields to his advances. Years later, she returns to the same spot with her husband, Anatole, an unromantic drip, and while he naps, she encounters Henri and recalls their brief encounter. The film is an exquisite mix of comedy and melancholy, the kind of subtle blending of tones Renoir is known for from his greatest films, The Grand Illusion (1937) and The Rules of the Game (1939). A Day in the Country was in fact never finished -- weather interrupted the shooting and Renoir had to move on to another commitment -- but the existing footage was assembled ten years later under the supervision of the producer, Pierre Braunberger, with two explanatory intertitles, and it stands on its own as a masterwork. In sharp contrast to the affectionately amused treatment of the bourgeoisie in A Day in the Country, Boudu Saved From Drowning is a raucous free-for-all centered on the great eccentric Michel Simon in the title role. Boudu is a tramp, a shaggy monster, who after his dog runs away decides to drown himself in the Seine. But he is rescued by Édouard Lestingois, a bookseller, who takes him into his home. Boudu proceeds to trash the place and seduce both Mme. Lestingois and the housemaid, who is also Lestingois' mistress. Simon's performance pulls out all the stops in one of the greatest comic tours de force in film history. If you want to see what épater la bourgeoisie really means, just watch Boudu.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)