A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Tuesday, January 19, 2016

Two Arabian Knights (Lewis Milestone, 1927)

The first ever Academy Awards, presented in 1929 for movies made in 1927 and 1928, included several categories that soon disappeared. There was one for "title writing," which the arrival of sound made obsolete, and the award for best picture was divided into two categories: "best production" and "unique and artistic production." The former was won by Wings (William A. Wellman, 1927), the latter by Sunrise (F.W. Murnau, 1927). The distinction between "best" and "unique and artistic" is opaque, so the Academy dropped the latter category the next year. But one category split that it might well have retained, given the Academy's blindness toward comedy over the years, was the distinction between "director, comedy picture," and "director, dramatic picture." Lewis Milestone became the sole winner of the former award, but he might have missed out on that opportunity if the Academy hadn't excluded Charles Chaplin from competition. Chaplin was instead given a special award as writer, director, producer, and star of The Circus (1928), probably because the Academy board knew that he would have swept the honors if allowed to compete for them. The trouble is, Two Arabian Knights is not terribly funny. It's a series of bits about two raffish American soldiers in World War I, who escape from a German prison camp and through a series of improbable circumstances wind up in "Arabia," where they rescue the daughter of an emir from marriage to a man she doesn't love. It's the stuff every Bob Hope, Bing Crosby, and Dorothy Lamour movie was made of, but without the talent and charisma. The soldiers are a high-born Philadelphian, W. Daingerfield Phelps III (William Boyd) and his sergeant, a New York cabbie named O'Gaffney (Louis Wolheim). The emir's daughter is played by Mary Astor, who has little to do besides roll her eyes over her veil. Milestone and Wolheim would be reunited, with much better results, in All Quiet on the Western Front (1930). Boyd was a popular leading man in silents and early talkies, but he fell on hard times before, in 1935, he landed a role in a Western as a character named Hopalong Cassidy. He played the part for the next two decades in scores of movies and a TV series. Two Arabian Knights also features Boris Karloff in a small role.

Monday, January 18, 2016

Her Night of Romance (Sidney Franklin, 1924)

They had faces then, as the saying goes. And they needed them because they didn't have voices. Constance Talmadge was not beautiful -- her heart-shaped face was too long, and the profile shots in Her Night of Romance reveal the beginnings of a double chin. It's suggestive that when we first see her in the movie, she is pretending to be ugly -- and succeeding in a hilarious way: When ordered by newspaper photographers to smile and show her teeth, she comes up with a grimace that looks like she's just bitten into a lemon. But she had huge eyes and knew how to act with them, showing what she was thinking -- and often what she was saying. The ugly duckling masquerade is prescribed by the plot, in which she is an American heiress arriving in England and trying to duck fortune-hunters. Naturally the first person who sees through her disguise is an impoverished lord (Ronald Colman), who has just put his mansion up for sale, so the plot (by Hanns Kräly) becomes a series of complications after her father (Albert Gran) buys the mansion. The rest is a series of mistaken identities and misunderstood motives common to romantic comedy. Colman was nearing the peak of the first phase of his career as a movie star, relying on his suave handsomeness and good comic timing. It was a career that lasted 40 years because, unlike many silent stars, he had a speaking voice that was as handsome as his face. Talmadge and her sister Norma, who was also a major silent star, were not so lucky: Neither had received vocal training that would have helped them lose their Brooklyn accents, so they left movies when sound arrived.

Sunday, January 17, 2016

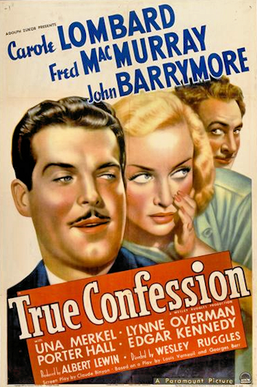

True Confession (Wesley Ruggles, 1937)

A somewhat too frantic screwball comedy, True Confession plays fast and loose not only with the legal profession but also to an extent with the careers of its stars. Fred MacMurray plays Kenneth Bartlett, a lawyer who insists on defending only those he thinks are really innocent, which gives him some trouble when his wife, Helen (Carole Lombard), goes on trial for murder. She's a would-be writer who can't always be trusted to tell the truth, so even though she didn't commit the crime, she winds up saying she did and pleading self-defense. Meanwhile, the trial is being watched by Charley Jasper (John Barrymore), an alcoholic loon who knows who really did the deed. None of these people make much sense, especially Barrymore, who seems at times to be reprising his earlier, far more successful performance as Oscar Jaffe opposite Lombard's Lily Garland (aka Mildred Plotka) in Twentieth Century (Howard Hawks, 1934). Alcohol had taken a serious toll on Barrymore, who was 55 when he made this film; he looks 70. Lombard was better, more controlled in her comic flights in Twentieth Century, too. Here she verges on grating at times. Comparisons are seldom fair, but it has to be said that the difference between the two films has to be that the earlier and better one was directed by Hawks from a screenplay by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur, and True Confession was directed by Wesley Ruggles from a screenplay by Claude Binyon based on a French farce. Still, there's some fun to be had here, and the cast includes such stars from the golden age of character actors as Una Merkel being giddy, Porter Hall being irascible, Edgar Kennedy doing multiple face-palms, and Hattie McDaniel playing one of her always watchable (if regrettable) roles as the maid.

The River (Jean Renoir, 1951)

The near-hallucinatory vividness of Technicolor was seemingly made for Jean Renoir, the son of the Impressionist painter Pierre-Auguste Renoir, but this film was his first use of the process. It's the more remarkable because he was working with his nephew (and Pierre-Auguste's grandson), Claude Renoir, the cinematographer, and neither director nor photographer was particularly experienced in shooting landscape, especially in the country of India, which is the real star of the film. The River has a distinctly Western attitude toward the country, viewing it through the eyes of its British residents. It's based on the experiences of Rumer Godden, the English writer who spent her childhood in India. Her screenplay, co-written with Jean Renoir, is about the tensions between cultures, using the Ganges, the titular river, as a symbol of both the eternal and the mutable. Ravishingly beautiful as the film is, it suffers from some major weaknesses in casting. Its central character, the teenager Harriet, is played by Patricia Walters, a nonprofessional who made no subsequent films and never quite seems at ease before the camera. As Capt. John, the American recovering from the loss of a leg during the war, Thomas E. Breen doesn't have the kind of charisma that would seem to have Harriet, her older friend Valerie (Adrienne Corri), and her Eurasian neighbor (Radha Burnier) falling over themselves to attract his attention. (Breen, incidentally, was both a real amputee from a war wound and the son of the enforcer of the Production Code, Joseph I. Breen.) But for those willing to overlook its flaws, which also include a lack of narrative urgency, The River rewards sympathetic attention and, as a film by a Frenchman about the English in India, stands as a landmark in postwar international filmmaking.

Saturday, January 16, 2016

La Pointe Courte (Agnès Varda, 1955)

|

| Philippe Noiret in La Pointe Courte |

Elle: Silvia Monfort

Director: Agnès Varda

Screenplay: Agnès Varda

Cinematography: Louis Soulanes, Paul Soulignac, Louis Stein

Film editing: Alain Resnais

Music: Pierre Barbaud

"They talk too much to be happy," says one of the villagers about the Parisian couple (Philippe Noiret and Silvia Monfort) who are spending time in a small fishing community on the Mediterranean. He has been in the town, where he was born, for several weeks, and she arrives to tell him that she wants a separation after four years of marriage. So they wander around, endlessly analyzing their relationship, as life goes on in the village: The townspeople argue with the authorities about where they can fish and about the bacterial count that has been detected in the water; a small child dies; a young man courts a girl over the objections of her father; a festival that involves jousting from boats takes place, and so on. The sophisticated self-analysis of the couple soon begins to look petty against the backdrop of the village's real problems. At one point in their dialogue, a scene is stolen from them by one of the village's many cats, whose playing around on a woodpile behind the couple becomes far more interesting than what they have to say. Aside from Noiret and Monfort, the actors are all actual residents of the village. Varda began as a still photographer, and her sense of composition is notable throughout this film, her first. She had spent time in Sète, the town where La Pointe Courte was filmed, as a teenager, and was photographing it for a friend when the idea of the movie came to her. It's often cited as one of the first films of the French New Wave, of which she became a prominent member, though seven years passed before she made her second and better-known film, Cléo From 5 to 7 (1962). Alain Resnais, who became one of the leading New Wave directors, edited La Pointe Courte, and the striking score is by Pierre Barbaud.

Night and Fog (Alain Resnais, 1955)

Cynics used to say that the surest way to win an Oscar for best documentary was to make a film about the Holocaust. But when Alain Resnais's Night and Fog was released, it not only received no Oscar nominations, but it was confronted by protests. The German government wanted it to be withdrawn from exhibition at the Cannes Film Festival, and the French censors objected to a scene in which a French police officer was shown guarding one of the deportation centers run by the Vichy government during the war. The French censors also objected to a sequence showing bodies being bulldozed into a mass grave. But it's a testimony to the power of Resnais's editing and the narrative written by Jean Cayrol, a survivor of the Mauthausen-Gusen camp, and spoken by Michel Bouquet, that although such images have grown distressingly familiar over the past 60 years, they still have their power to shock the conscience. It sounds tediously moralizing to reiterate, but every time a politician today tries to dehumanize whatever group is currently out of favor, these images should come to mind.

Friday, January 15, 2016

Hiroshima Mon Amour (Alain Resnais, 1959)

I remember the long dorm-room discussion after my friends and I saw this film for the first time, so I was surprised on returning to it after so many years how conventional the elements we talked about now seem. The extended use of documentary clips at the beginning of the film, with the voiceover by the lovers (Emmanuelle Riva and Eiji Okada) arguing about whether she had really seen anything in Hiroshima, seemed to us a bafflingly random way to start a movie. The jump cuts into and out of flashbacks confused us. What, we argued, did it signify that their entwined bodies, seemingly covered with ashes, then began to glow? (Today, I'm afraid some sarcastic voice will pipe up to say, "They've been glitter-bombed.") Why does she refer to her Japanese lover as "you" when she's actually talking about the German she loved during the war? Is the movie really about sleeping with the enemy? Doesn't it trivialize the horror of Hiroshima to bring it down to the level of the background for a love affair? Today, we'd regard those questions as naive, and I'm certain we wouldn't be confused by the film's structure, which is a way of saying that Resnais and his screenwriter, Marguerite Duras, really did succeed in revolutionizing movies. But if no one is startled by jump cuts or unconventional narrative devices today, there remains a raw immediacy about the film that no subsequent imitators have ever quite succeeded in equaling. Much credit also has to go to the score by Georges Delerue and Giovanni Fusco, and to the editing by Michio Takahashi and Sacha Vierny.

Far From the Madding Crowd (Thomas Vinterberg, 2015)

It's not really easy for me to comment on one version of the Thomas Hardy novel after just commenting on another without resorting to comparisons, so I won't even try to avoid them. One unavoidably obvious difference between the 2015 film and the 1967 John Schlesinger version is visual. In Schlesinger's film, despite the fine cinematography of Nicolas Roeg, the interiors seem impossibly overlighted for a period that resorted to candles and oil lamps for illumination. The change in film technology now makes it possible for us to see the way people once lived -- in a realm of darkness and shadows. (We can almost precisely date when this change in cinematography took place: in 1975, when director Stanley Kubrick and cinematographer John Alcott worked with lenses specially designed for NASA to create accurately lighted interiors for Barry Lyndon. Since then, the digital revolution has only added to the arsenal of lighting effects available to filmmakers.) So cinematographer Charlotte Bruus Christensen's adds an element of texture and mystery to Thomas Vinterberg's version that was technologically unavailable to Roeg, and not only in interiors but also in night scenes, such as the first encounter of Bathsheba (Carey Mulligan) and Sgt. Troy (Tom Sturridge), when he gets his spur caught in the hem of her dress. The scene is meant to take place by the light of the lamp she is carrying, which Christensen accomplishes more successfully than Roeg was able to. But the story's the thing, and David Nicholls's screenplay is much tighter than Frederic Raphael's 1967 version -- it's also about an hour shorter. Nicholls makes most of his cuts toward the end of the film, omitting for example the episode in which Troy becomes a circus performer, one of the more entertaining sections of the Schlesinger-Raphael version. I think Nicholls's screenplay sets up the early part of the stories of Bathsheba and Gabriel Oak (Matthias Schoenaerts) much better, though he has to resort to a brief voiceover by Mulligan at the beginning to make things clear. His account of the affair of Troy and the ill-fated Fanny Robbin (Juno Temple) is less dramatically detailed than Raphael's, but in neither film is their relationship dealt with clearly enough to make us understand Troy's character. On the whole, I think I prefer the new version, which is less star-driven than Schlesinger's, but I can't really say whether I would feel that way if I had seen the new one first.

Thursday, January 14, 2016

Far From the Madding Crowd (John Schlesinger, 1967)

People always complain about the way movies change the stories of their favorite novels, but screenwriter Frederic Raphael's adaptation of Thomas Hardy's novel shows why such changes are necessary. Raphael remains faithful to the plot, with the result that characters become far more enigmatic than Hardy intended them to be. We need more of the backstories of Bathsheba Everdeen (Julie Christie), Gabriel Oak (Alan Bates), William Boldwood (Peter Finch), and Frank Troy (Terence Stamp) than the highly capable actors who play them can give us, even in a movie that runs for three hours -- including an overture, an intermission, and an "entr'acte." These trimmings are signs that the producers wanted a prestige blockbuster like Doctor Zhivago (David Lean, 1965), which had also starred Christie. But Hardy's works, with their characters dogged by fate and chance, don't much lend themselves to epic treatment. John Schlesinger, a director very much at home in the cynical milieus of London in Darling (1965) and Sunday Bloody Sunday (1971) and New York in Midnight Cowboy (1969), doesn't show much feeling for Hardy's rural, isolated Wessex, where the weight of tradition and the indifference of nature play substantial roles. What atmosphere the film has comes from cinematographer Nicolas Roeg's images of the Dorset and Wiltshire countryside and from Richard Rodney Bennett's score, which received the film's only Oscar nomination.

Wednesday, January 13, 2016

The Postman Always Rings Twice (Tay Garnett, 1946)

It's one of the most memorable entrances in movies. Actually, her lipstick enters first, rolling across the floor toward him. She is Cora Smith and he is Frank Chambers, the man her husband has just hired to work in their roadside café/filling station. But more important, she is Lana Turner, one of the last of the products of the resources of the studio star factories: lighting, hair, makeup, wardrobe, and especially public relations. And he is John Garfield, one of the first of a new generation of Hollywood leading men, trained on the stage, and with an urban ethnicity about him: His vaguely presidential nom de théâtre thinly disguises his birth name, Jacob Julius Garfinkle. The pairing shouldn't work: She's a goddess, not an actress, whom the publicists had turned into "the Sweater Girl" while claiming that she had been discovered at a drugstore soda fountain. He was the child of Ukrainian-born Jews and grew up on the Lower East Side, trained as a boxer and studied acting with various disciples of Stanislavsky. But the chemistry is there from the moment Frank picks up Cora's lipstick and the camera surveys her from toe to head: white shoes, tan legs, white shorts, tan midriff, white halter top, blond hair, white turban. She reaches out her hand for the lipstick, but he doesn't move, so she comes over and gets it. It's one of the many power plays that will take place between them. The rest is one of the great film noirs, from a studio that didn't usually make them, MGM. In fact, the studio head, Louis B. Mayer, hated it, which is always a good recommendation: He hated Sunset Blvd. (Billy Wilder, 1950), too. (Mayer's tastes ran to Jeanette MacDonald-Nelson Eddy operettas and the Andy Hardy series.) It's the only really memorable movie directed by Tay Garnett, so I suspect a lot of credit goes to the screenwriters, Niven Busch and Harry Ruskin, and to their source, James M. Cain's overheated novel. Cain also wrote the novels that were the basis of two other famous noirs: Double Indemnity (Billy Wilder, 1944) and Mildred Pierce (Michael Curtiz, 1945), so the screenwriters and the director had some powerful examples to follow.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)

_poster.jpg)