A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Sunday, March 27, 2016

The Manchurian Candidate (John Frankenheimer, 1962)

Although Stanley Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove (1964) is by far the more celebrated film, I think as satire The Manchurian Candidate is a more subtle and sophisticated response to the Cold War. It may have fallen out of favor too soon because its subject, political assassination, became so sensitive just a month after its release, when John F. Kennedy was shot. For reasons that remain unclear, including Frank Sinatra's purchase of the distribution rights, it fell out of release for a long time, and only resurfaced occasionally on television until 1987, when, after a screening at the New York Film Festival, it became available on video. It's a loopy, scary, often hilarious, sometimes puzzling, and -- especially in any election year -- absolutely essential American film. Frankenheimer, who was one of the pioneers of American television drama in the age of shows like Playhouse 90, never developed a distinctive style in his movie work, but he knew how to tell a story, even when the story is as convoluted as this one. With George Axelrod, he adapted the 1959 thriller by Richard Condon, sometimes lifting dialogue direct from the novel. The results are occasionally enigmatic, as in the meeting of Marco (Sinatra) with Eugenie Rose Chaney (Janet Leigh) on the train, where the dialogue shifts into the surreal and seems to be laden with code. In terms of plot, the encounter -- probably the oddest meeting on a train since Cary Grant and Eva Marie Saint's characters met in North by Northwest (Alfred Hitchcock, 1959) -- goes nowhere: Leigh's character serves no further discernible role in the narrative. But it serves nicely to keep the viewer off guard as things grow increasingly bizarre. The weakest performance in the film is probably that of Laurence Harvey as Raymond Shaw. Harvey can't seem to be bothered to keep up an American accent, but somehow even that fits the ambiguity of his character. Angela Lansbury, as Raymond's mother (this is the point where it's usual to mention that she was only three years older than Harvey), is absolutely terrifying as one of the movies' greatest female villains. It earned her an Oscar nomination, but she lost to Patty Duke in The Miracle Worker (Arthur Penn). James Gregory, as her Joe McCarthy-like husband, would not be out of place in the current presidential campaign.

Saturday, March 26, 2016

Blow-Up (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1966)

Back in the day we would discuss for hours the significance of Thomas (David Hemmings) fetching an invisible tennis ball after having photographed an invisible murder. Then later we scrutinized the thematic relationship of Blow-Up to Antonioni's great trilogy of L'Avventura (1960), La Notte (1961), and L'Eclisse (1962). More recently, Blow-Up has figured large in discussions of the "male gaze." But lately it has become a historical artifact from a time and place half a century ago, the "swinging London" of the mid-1960s. And there I think it best belongs. What perhaps needs to be discussed is the tone of the film: Is it a document, or a celebration, or an exposé, or a satire? I think it is a bit of all of these, but mostly the tone is satiric. Thomas's aesthetic detachment, not to say voyeurism, makes him the perfect vehicle for an exploration of the era, from the grim flophouse he spends a night photographing to the drug-addled home of the wealthy, by way of a fashion shoot, a glimpse of what seems to be adulterous affair but may be a murder, a mini-orgy with some teenyboppers, a peek at two of his friends making love, and a performance in a rock club. All of it viewed with the impassive gaze of Thomas, Antonioni, and Carlo Di Palma's movie camera. Is it meant to be funny? Yes, sometimes, as when Thomas encounters the model Verushka at the party and says, "I thought you were supposed to be in Paris," and she replies, "I am in Paris." Or when we see the audience watching the performance of the Yardbirds in the club, showing no signs of enjoyment, but then going crazy when Jeff Beck smashes his guitar and flings it into the audience. Thomas escapes from the club with a piece of it, eludes the pursuing crowd, but throws it away when he realizes it's worthless. (A passerby picks it up, looks it it, and tosses it away.) It's a portrait of a cynical era in which people, as Oscar Wilde put it, know "the price of everything and the value of nothing." Hemmings, with his debauched choirboy* face, is the perfect protagonist, and Vanessa Redgrave, at the start of her career, is beautifully, magnificently enigmatic as the woman who may or may not have been involved in murder. I'm not sure it's a great film -- certainly not in comparison to Antonioni's trilogy -- but it will always be a fascinating one.

*Almost literally: Hemmings started as a boy soprano who was cast by Benjamin Britten in several works, most notably as Miles in the 1954 opera The Turn of the Screw. He can be heard on the recording made that year with Britten conducting.

*Almost literally: Hemmings started as a boy soprano who was cast by Benjamin Britten in several works, most notably as Miles in the 1954 opera The Turn of the Screw. He can be heard on the recording made that year with Britten conducting.

Friday, March 25, 2016

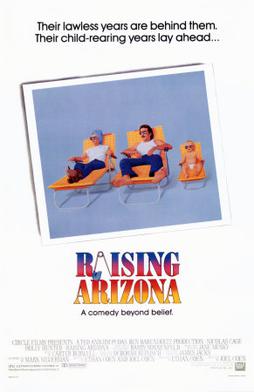

Raising Arizona (Joel Coen and Ethan Coen, 1987)

Raising Arizona was the Coen brothers' second movie, and they never made another quite as broadly comic as this one. Even The Big Lebowski (1998) and O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000) seem restrained in comparison. I found that it took a little getting used to on this viewing: Everyone in it (including the baby) is a caricature, a live-action version of a Warner Bros. cartoon character. Maybe I reacted this way because I recently saw Holly Hunter in the deadly serious role of Ada in The Piano (Jane Campion, 1993) and had forgotten what a gifted farceuse she could be when she sets her tight little mouth in that determined line and barrels ahead. Nicolas Cage was still in that goofy hangdog persona he used in Peggy Sue Got Married (Francis Ford Coppola, 1986) and only began to grow out of the next year in Moonstruck (Norman Jewison, 1987). But the real surprise for me was Frances McDormand, going completely over the top as Dot, the scatterbrained mother of the most odious bunch of brats ever seen on film. She was at the beginning of her career as a serious actress and would follow up Raising Arizona with her first Oscar nomination for Mississippi Burning (Alan Parker, 1988), so seeing her go all loosey-goosey in this film was a revelation. It's by no means among my favorite Coen brothers movies, and watching it in the company of their best -- among which I'd put Fargo (1996), No Country for Old Men (2007), and Inside Llewyn Davis (2013) -- would probably show up some of its flaws, but why would you want to do that? Sometimes silly fun is enough. At only a touch over an hour and a half, Raising Arizona doesn't hang around long enough to wear out its welcome.

Thursday, March 24, 2016

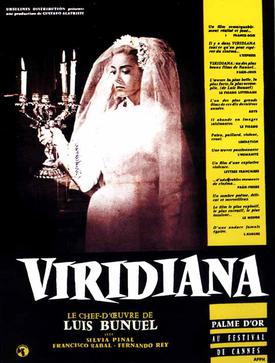

Viridiana (Luis Buñuel, 1961)

TCM this month has been running a series of movies condemned by the Catholic Legion of Decency, with commentary by Sister Rose Pacatte. Sister Rose doesn't have a lot of screen presence, but she does a good job of explaining why the Legion in its heyday found the movies objectionable -- and suggesting why they really aren't. It's hard to believe today that Viridiana, with its heavily moral tone, was once considered blasphemous, but ours is a day when anything sacred is routinely held up for scrutiny. It's the first work of Buñel's greatest period as writer-director, and while it doesn't quite rise to the exalted standard of Belle de Jour (1967) or The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972), it wrangles effectively with their topics, including middle-class morality and the repressive element of Catholicism. Silvia Pinal gives the title role credibility, moving from naïveté through disillusionment to a final note of ambiguity: Has Viridiana truly fallen from the grace she has so ardently sought? The film is also a triumph of casting, not only in the key roles of Don Jaime (Fernando Rey), Viridiana's lecherous, tormented uncle, and Jorge (Francisco Rabal), his equally lecherous but profoundly untormented bastard son, but also Margarita Lozano as Ramona, Don Jaime's and later Jorge's maid-mistress, and Teresa Rabal as Rita, Ramona's sly, sneaky daughter, And then there's the gallery of grotesques, the beggars whom Viridiana naively takes in and tries to care for. Is there a more horrifying scene than the one that culminates in Buñuel's famous parody of Leonardo's The Last Supper, in which the beggars nearly destroy Don Jaime's house, which Jorge is trying to restore? It can be argued that the avaricious Jorge gets what's coming to him, of course, but Buñuel is never as simplistic as that, viz., the deep ambiguity of the closing scene in which the virtuous Viridiana has let down her hair and forms a threesome -- at the card table but where else? -- with Jorge and Ramona.

Wednesday, March 23, 2016

The King of Comedy (Martin Scorsese, 1982)

Is there anything scarier than Robert De Niro's smile? It's what makes his bad guys, like Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver (Martin Scorsese, 1976) or Max Cady in Cape Fear (Scorsese, 1991), so unnerving, and it's what keeps us on the edge of our seats throughout The King of Comedy. Rupert Pupkin isn't up to anything so murderous as Travis or Max, but who knows what restrains him from becoming like them? As a satire on the nature of celebrity in our times, Paul D. Zimmerman's screenplay doesn't break any new ground. But what keeps the movie from slumping into predictability are the high-wire, live-wire performances of De Niro and Sandra Bernhard as the obsessive fans and the marvelously restrained one of Jerry Lewis as late night talk-show host Jerry Langford, the object of their adulation. And, of course, Scorsese's ability to keep us guessing about what we're actually seeing: Is this scene taking place in real life, or is it a product of Rupert's deranged imagination? That extends to the movie's ending, in which Rupert, having kidnapped Langford and engineered a debut on network television, is released from prison and becomes a celebrity himself. Are we to take this as the film's comment on fame, like the phenomenon of Howard Beale in Network (Sidney Lumet, 1976) and any number of people (many of them named Kardashian) who have become famous for mysterious reasons? (Incidentally, the odd thing about Rupert's standup routine is not that it's bad, but that it's exactly the sort of thing that one might have sat through while watching a late night show in 1982.) I prefer to think that we are still in Rupert's head at film's end -- it seems less formulaic that way. I don't know of a movie that stays more unbalanced and itchy from scene to scene.

Tuesday, March 22, 2016

The Piano (Jane Campion, 1993)

If Jane Campion had gone with her original plan, Ada (Holly Hunter) would have gone down with her piano like Ahab lashed to the whale. The comparison to Moby-Dick is not, I think, terribly far-fetched: The Piano is one of those works, like the Melville novel, that tempt one into symbolic interpretations. Ada's obsession with her piano is, in its own way, like Ahab's obsession with the white whale, a kind of representation of the extreme irrational nexus of mind and object. But in Campion's completed version, Ada loses only a finger, not her life, and the piano is replaced along with the finger. Does this resort to a happy ending vitiate Campion's film, or should we accept as a given that life does in fact sometimes work that way? I think in a movie as enigmatic as The Piano so often is, Campion has blunted the emotional impact by having Ada and Baines (Harvey Keitel) wind up together in what seems to be a pleasant home far from the wilderness in which most of the film takes place, she teaching piano with her hand-crafted prosthetic and learning to speak, as Flora (Anna Paquin), that devious, semi-feral child, turns cartwheels. (Flora puts me in mind of another child of the wilderness in another work of impenetrable symbolism, Pearl in The Scarlet Letter.) Happily ever after seems like a lie in the mysterious terms with which the film began. We never learn why Ada turned mute, or who Flora's father was and what happened to him, or why she agrees to move to New Zealand to marry and then spurn Stewart (Sam Neill), or find a way to resolve any number of other enigmas. But the great strength of the film lies its power to evoke the imponderable, to make us wonder about Baines's life among the Maori, about the persistence of an imperialist culture (women wearing hoopskirts and men in top hats) in an alien land, about the nature of awakening sexuality, about the function of art, about the tension between innocence and experience in a child's life, and so on. It is, I'm certain, a great film, just because it is so hard to grasp and reduce to a formula.

Links:

Anna Paquin,

Harvey Keitel,

Holly Hunter,

Jane Campion,

Sam Neill,

The Piano

Monday, March 21, 2016

The Devil's Eye (Ingmar Bergman, 1960)

|

| Jarl Kulle and Bibi Andersson in The Devil's Eye |

Sunday, March 20, 2016

Sawdust and Tinsel (Ingmar Bergman, 1953)

When this movie was first released in the United States it was called The Naked Night, probably by exhibitors who wanted to cash in on the reputation Swedes had gained for being sexy, but especially because the film's star, Harriet Andersson, had just appeared in the nude in Summer With Monika (Ingmar Bergman, 1953), which had been passed off in some markets as a skin flick. By the time I first saw it, sometime in the 1960s, it had been renamed Sawdust and Tinsel. (The Swedish title, Gycklarnas Afton, can be translated as something like "Evening of a Clown.") Frankly, the first time I saw it, I found it tedious and heavy-handedly sordid, with its shabby, bankrupt circus and its frustrated, destructive relationships. Having grown older and perhaps somewhat wiser, I don't hate it anymore, but I can't see it as the masterpiece some do. It seems to me to lean too heavily on the familiar trope of the circus as a microcosm of the world, and on emphasizing the grunge (sawdust) and fake glamour (tinsel) of its currently prevalent title. What it has going for it is the awesome cinematography by Sven Nykvist: It was his first film for Bergman; they didn't work together again until 1960 and The Virgin Spring, but it became one of the great partnerships in filmmaking. The opening sequence of the tawdry little circus caravan trundling across the landscape is superbly filmed, and I can't help wondering if Bergman and Gunnar Fischer, the cinematographer of The Seventh Seal (1957), didn't have it in mind when they created the iconic shot of Death and his victims silhouetted against the sky in that later film. The performances, too, are excellent: Åke Grönberg as Albert, the worn-out circus owner; Andersson as his restless mistress, Anne; Hasse Ekman as Frans, the actor who rapes her; Anders Ek as the half-mad clown, Frost; and Annika Tretow as Albert's wife, who has gone on to be a success in business after he left her. But the story is heavily formula-driven: There is, for example, a rather clichéd sequence in which Albert toys with suicide, which too obviously echoes an earlier moment when Frans hammily rehearses a scene in which he kills himself while Anne watches offstage. In the end, the movie is rather like a version of Pagliacci without the benefit of Leoncavallo's music. After a disastrous performance of the circus, someone actually says, "The show's over," which is pretty much a steal from the final line of Pagliacci: "La commedia è finita!"

Saturday, March 19, 2016

Moulin Rouge (John Huston, 1952)

If Moulin Rouge had a screenplay worthy of its visuals, it would be a classic. As it is, it's still worth seeing, thanks to a stellar effort to bring to life Toulouse-Lautrec's paintings and sketches of Parisian nightlife in the 1890s. The screenplay, by Anthony Veiller and director Huston, is based on a novel by Pierre Le Mure, the rights to which José Ferrer had purchased with a view to playing Lautrec. He does so capably, subjecting himself to some real physical pain: Ferrer was 5-foot-10 and Lautrec was at least a foot shorter, owing to a childhood accident that shattered both his legs, so Ferrer performed many scenes on his knees, sometimes with an apparatus that concealed his lower legs from the camera. But that is one of the least interesting things about the movie, as is the rather conventional story of the struggles of a self-hating, alcoholic artist. What distinguishes the film is the extraordinary production design and art direction of Marcel Vertès and Paul Sheriff, and the dazzling Technicolor cinematography of Oswald Morris. Vertès and Sheriff won Oscars for their work, but Morris shockingly went unnominated. The most plausible theory for that oversight is that Sheriff clashed with the Technicolor consultants over his desire for a palette that reproduced the colors of Lautrec's art: The Technicolor corporation was notoriously persnickety about maintaining control over the way its process was used. It's possible that the cinematography branch wanted to avoid future hassles with Technicolor by denying Morris the nomination. (Ironically, one of the more interesting incidents from Lautrec's life depicted in the film involves his clashes with the lithographer over the colors used in posters made from his work.) The extraordinary beauty of the film and some lively dance sequences that bring to life performers such as La Goulue (Katherine Kath) and Chocolat (Rupert John) make it memorable. There are also good performances from Colette Marchand as Marie Charlet and Suzanne Flon as Myriamme Hayam. And less impressive work from Zsa Zsa Gabor, playing herself more than Jane Avril, and lipsynching poorly to Muriel Smith's voice in two songs by Georges Auric.

Friday, March 18, 2016

A Lesson in Love (Ingmar Bergman, 1954)

|

| Eva Dahlbeck and Gunnar Björnstrand in A Lesson in Love |

David Erneman: Gunnar Björnstrand

Susanne Verin: Yvonne Lombard

Nix Erneman: Harriet Andersson

Carl-Adam: Åke Grönberg

Prof. Henrik Erneman: Olof Winnerstrand

Svea Erneman: Renée Björling

Pelle: Göran Lundquist

Director: Ingmar Bergman

Screenplay: Ingmar Bergman

Cinematography: Martin Bodin

In A Lesson in Love, Ingmar Bergman seems to be trying to turn Eva Dahlbeck into Carole Lombard. She certainly has Lombard's blond glamour, and she makes a surprising go at knockabout comedy. But where Lombard had the light touch of a Howard Hawks or an Ernst Lubitsch to guide her in her best work, Dahlbeck is in the hands of Bergman, whose touch no one has ever called light. A year later, the Bergman-Dahlbeck collaboration would make a better impression with Smiles of a Summer Night, but A Lesson in Love sometimes verges on smirkiness in its treatment of the marriage of Marianne and David Erneman. They are on the verge of divorce and she is about to marry her old flame Carl-Adam, a sculptor for whom she once posed. David is a gynecologist who has had a series of flings with other women, including Susanne, with whom he is trying to break up. But Marianne has not exactly been faithful to their vows either. Meanwhile, we also get to know their children, Nix and her bratty little brother, Pelle, and David's parents, who in sharp contrast to Marianne and David are celebrating 50 years of marriage. While Bergman sharply delineates all of these characters -- especially 15-year-old Nix, who hates being a girl so much that she asks her father if he can perform sex-change operations -- the semi-farcical situation he puts them has a kind of aimless quality to it. I appreciated Harriet performance as Nix the more for having seen her as the dying Agnes in Bergman's Cries and Whispers (1972) the night before, but in this film her role makes no clear thematic sense.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)