A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Wednesday, April 6, 2016

Radio Days (Woody Allen, 1987)

Woody Allen's warmest and maybe most irresistible film has none of the neurotic obsession gags or existentialist angst shtick that are so often associated with his work. It's a simple piece about the nostalgia that old songs evoke in us -- in Allen's case, reminiscences of the days when radio was the dominant, almost ubiquitous medium in people's lives, before television held people captive in their living rooms or the internet addicted them to the little screens of their cell phones or tablets. Specifically, it's Allen's childhood as seen through the eyes of young Joe (Seth Green) and his parents (Julie Kavner and Michael Tucker) and extended family. It's also, secondarily, a tribute to many of the actors who have enlivened Allen's films, with smaller roles and cameos filled by Dianne Wiest, Mia Farrow, Danny Aiello, Jeff Daniels, Tony Roberts, Diane Keaton, and many others. Production designer Santo Loquasto deservedly received an Oscar nomination for his re-creation of Queens and Manhattan in the late 1930s and early 1940s, but honors should go to the luminous cinematography of Carlo Di Palma, too. The soundtrack, supervised by Dick Hyman, ranges from such true classics as Kurt Weill's "September Song" and Duke Ellington's "Take the 'A' Train" to novelty pop of the period like "Mairzy Doats" and "Pistol Packin' Mama." As one born B.T. (Before Television), I can really dig it.

Tuesday, April 5, 2016

High and Low (Akira Kurosawa, 1963)

High and Low begins surprisingly, considering that Kurosawa is known as a master director of action, with a long static sequence that takes place in one set: the living room of the home of Kingo Gondo (Toshiro Mifune), an executive with a company called National Shoe. The sequence, almost like a filmed play, depicts Gondo's meeting with the other executives of the company, who are trying to take it over, believing that the "Old Man" who runs it is out of touch with the shoe market. Gondo, however, thinks the company should focus on well-made, stylish shoes rather than the flimsy but fashionable ones the others are promoting. After the others have gone, we see that Gondo has his own plan to take over the company with a leveraged buyout -- he has mortgaged everything he has, included the opulent modern house in which the scene takes place. But suddenly he receives word that his son has been kidnapped and the ransom will take every cent that he has. Naturally, he plans to give in to the kidnappers' demands -- until he learns that they have mistakenly kidnapped the wrong child: the son of his chauffeur, Aoki (Yutaka Sada). Should he go through with his plans to ransom the boy, even though it will wipe him out? Enter the police, under the leadership of Chief Detective Tokura (Tatsuya Nakadai), and the scene becomes a complicated moral dilemma. Thus far, Kurosawa has kept things stagey, posing the group of detectives, Gondo, his wife (Kyoko Kagawa), his secretary (Tatsuya Mihashi), and the chauffeur in various permutations and combinations on the Tohoscope widescreen. But once a decision is reached -- to pay the ransom and pursue the kidnappers -- Kurosawa breaks free from the confinement of Gondo's house and gives us a thrilling manhunt, the more thrilling because of the claustrophobic opening segment. The original title in Japanese can mean "heaven and hell" as well as "high and low," and once we move away from Gondo's living room we see that his house sits high on a hill overlooking the slums where the kidnapper (Tsutomu Yamazaki) lives, and from which he can peer into Gondo's house through binoculars. We return to the police procedural world of Stray Dog (Kurosawa, 1949), where sweaty detectives track the kidnapper through busy nightclubs and the haunts of drug addicts, and Kurosawa's cameras -- under the direction of Asakazu Nakai and Takao Saito -- give us every sordid glimpse. It's a skillful thriller, based on one of Evan Hunter's novels written under the "Ed McBain" pseudonym, done with a masterly hand. And while it's not one of Kurosawa's greater films, it has unexpected moral depth, enhanced by fine performances, including a restrained one by Mifune -- this time, the freakout scene goes to Yamazaki's kidnapper.

Monday, April 4, 2016

Stray Dog (Akira Kurosawa, 1949)

Toshiro Mifune and Takashi Shimura, who starred in Seven Samurai, appeared together five years earlier in this noir detective story. In a crowded bus on a sweltering day, Murakami (Mifune), a rookie homicide detective, has his gun stolen by a pickpocket. He gives chase but loses the thief, and shamefacedly has to report it to headquarters. To make matters worse, he soon discovers that the gun has been used in a robbery, wounding the victim. He begins a dogged search for the gun. In an extended sequence Kurosawa's depiction of police work takes us into the lower depths of post-war Tokyo as Murakami follows a lead that suggests the gun may have been sold on the underground gun market. Murakami's guilt becomes more intense after ballistics work reveals that his gun had been used in a robbery homicide and he witnesses the grief of the victim's husband. But he's teamed up with a veteran detective, Sato (Shimura), who persuades Murakami not to quit the force and accompanies him in an effort to retrieve the weapon. It's not only a well-made thriller but also a complex portrait of the lingering effects of the war on the Japanese populace, peering into sleazy nightclubs and cobbled-together hovels. Mifune and Shimura are a fine team, with the former far more restrained than he was in Seven Samurai and the latter adding a deeper note of warmth to the quiet integrity he demonstrated as the leader of the samurai band. Keiko Awaji plays the nightclub dancer who knows the hangouts of the gunman (Isao Kimura, who played the naive young samurai Katsushiro in the later film) but is reluctant to give him up. A vivid supporting cast and Asakazu Nakai's atmospheric cinematography make this more than just a skillful reworking of an American genre movie.

Sunday, April 3, 2016

Seven Samurai (Akira Kurosawa,1954)

It's a truism -- one that I've often echoed -- that silent movies and talkies constitute two distinct artistic media, and to judge the one by the standards of the other is an error. But it's almost impossible to watch films made by older directors, especially those who came of age when silent films were being made, without noticing the efforts they make to tell their stories without speech. It's true of John Ford, Alfred Hitchcock, and Howard Hawks, even though they, especially Hawks, became masters of dialogue in their films. And it's true of Kurosawa, who although he didn't begin his career in films until 1936 and directed his first one in 1943, was born in 1910 and grew up with silent movies. I think it helped him learn the universals of storytelling that are independent of language, so that he became the most popular of all Japanese filmmakers. Others rank the work of Ozu or Mizoguchi more highly, but Kurosawa's films manage to transcend the limitations of subtitles more easily. Of none of his films is this more true than Seven Samurai, which is also generally regarded, even by those with reservations about Kurosawa's work, as his masterpiece. That's not a word I use lightly, but having sat enthralled through the uncut version, three hours and 27 minutes long, last night, I'm willing to endorse it. It's an exhilarating film, with none of the longueurs that epics -- I'm thinking of Gone With the Wind (Victor Fleming, 1939) and Lawrence of Arabia (David Lean, 1962) -- so easily fall into. I don't know of any action film with as many vividly drawn characters, and that's largely because Kurosawa takes the time to delineate each one. It's also a film about its milieu, 16th-century Japan, although as its American imitation, The Magnificent Seven (John Sturges, 1960), shows, there's a universality about the antagonism between fighters and farmers. Kurosawa captures this particularly well in the character of Kikuchiyo (Toshiro Mifune), the would-be samurai who reveals in mid-film that he was raised as a farmer and carried both a kind of self-hate for his class along with a hatred for the arrogant treatment of farmers by samurai. Mifune's show-off performance is terrific, but the film really belongs to Takashi Shimura, who radiates stillness and wisdom as Kambei Shimada, the leader of the seven. There are clichés to be found, such as the fated romance of the young samurai trainee Katsushiro (Isao Kimura) and the farmer's daughter Shino (Keiko Tsushima), but like the best clichés, they ring true. Seven Samurai earned two Oscar nominations, for So Matsuyama's art direction and Kohei Ezaki's costumes, but won neither. Overlooking Kurosawa's direction, Shimura's performance, and Asakazu Nakai's cinematography is unforgivable, if exactly what one expects from the Academy.

Saturday, April 2, 2016

No Regrets for Our Youth (Akira Kurosawa, 1946)

| Setsuko Hara in No Regrets for Our Youth |

Friday, April 1, 2016

Funny Face (Stanley Donen, 1957)

Is there anything better than Astaire singing Gershwin? And in Funny Face he sings five Gershwin songs with his impeccable phrasing and musicianship, which in itself would be enough to make this one of the great film musicals. Okay, maybe it's not up there with the best of the Astaire-Rogers films or The Band Wagon (Vincente Minnelli, 1953), but it's close enough. And he dances, too, with the same grace and vitality at the age of 58 as when he was much, much younger, especially in his great solo performance of "Let's Kiss and Make Up" and his duet with Kay Thompson on "Clap Yo' Hands." So Audrey Hepburn isn't in the same league as Ginger Rogers or Cyd Charisse as a dance partner, but she had studied ballet when she was much younger and her solo number parodying modern dance moves is one of the film's highlights. As a singer, she's a good actress, by which I mean that her big solo number, "How Long Has This Been Going On?", is memorable because of the way she sells the concept of innocence awakening to ecstasy, greatly aided by a big yellow hat and Ray June's gorgeous color cinematography. It's clear that she had a small, untrained singing voice, which is why Marni Nixon had to be called in to dub her in My Fair Lady (George Cukor, 1964), a role that makes demands she probably couldn't have met vocally. There are those who are bothered by the nearly 30-year age discrepancy between Astaire and Hepburn, but she spent much of her career playing opposite much older men like Humphrey Bogart, Gary Cooper, and Cary Grant -- in her prime in the 1950s and early '60s, there were very few leading men her age who could match her star power. Some critics also object to the film's mockery of French intellectuals -- Pauline Kael calls the lecherous philosopher played by Michel Auclair "a sour idea" -- but that's probably asking too much of the conventions of romantic comedy. The screenplay is by Leonard Gershe, but the real heroes of the film are Astaire, Hepburn, Thompson, June, Roger Edens in his dual role as producer and composer, costume designers Edith Head and Hubert de Givenchy, photographer Richard Avedon as "visual consultant," and most of all Stanley Donen, who not only directed but shared choreography duties with Astaire and Eugene Loring.

Thursday, March 31, 2016

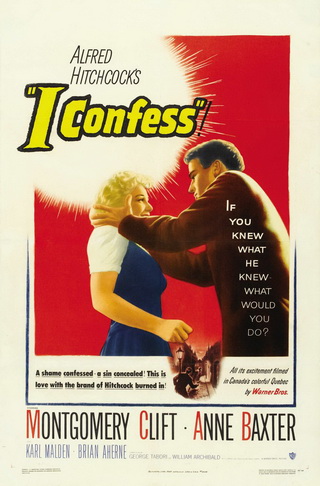

I Confess (Alfred Hitchcock, 1953)

I Confess is generally recognized as lesser Hitchcock, even though it has a powerhouse cast: Montgomery Clift, Anne Baxter, and Karl Malden. It also has the extraordinary black-and-white cinematography of Robert Burks, making the most of its location filming in Québec. Add to that a provocative setup -- a priest learns the identity of a murderer in confession but is unable to reveal it even when he is put on trial for the murder -- and it's surprising that anything went wrong. I think part of the reason for the film's weakness may go back to the director's often-quoted remark that actors are cattle. This is not the place to discuss whether Hitchcock actually said that, which has been done elsewhere, but the phrase has so often been associated with him that it reveals something about his relationship with actors. It's clear from Hitchcock's recasting of certain actors -- Cary Grant, James Stewart, Grace Kelly, Ingrid Bergman -- that he was most comfortable directing those he could trust. And Clift's stiffness and Baxter's mannered overacting suggest that Hitchcock felt no particular rapport with them. But I Confess also played directly into the hands of the censors: The Production Code was administered by Joseph Breen, a devout Catholic layman, and routinely forbade any material that reflected badly on the clergy. In the play by Paul Anthelme and the first version of the screenplay by George Tabori, the priest (Clift) and Ruth Grandfort (Baxter) have had a child together, and the murdered man (Ovila Légaré) is blackmailing them. Moreover, because he is prohibited from revealing what was told him in the confessional and naming the real murderer (O.E. Hasse), the priest is convicted and executed. Warner Bros., knowing how the Breen office would react, insisted that the screenplay be changed, and when Tabori refused, it was rewritten by William Archibald. The result is something of a muddle. Why, for example, is the murderer so scrupulous about confessing to the priest when he later has no hesitation perjuring himself in court and then attempting to kill the priest? No Hitchcock film is unwatchable, but this one shows no one, except Burks, at their best.

Wednesday, March 30, 2016

Scenes From a Marriage (Ingmar Bergman, 1973)

|

| Erland Josephson and Liv Ullmann in Scenes From a Marriage |

Tuesday, March 29, 2016

Touch of Evil (Orson Welles, 1958)

Monday, March 28, 2016

Schindler's List (Steven Spielberg, 1993)

Amid the nearly universal acclaim for Schindler's List, two major criticisms are often heard. One is that Spielberg tends toward the sentimental, especially at the end of the film: He lets Schindler's remorse at having not been able to save more Jews from the Holocaust go on too long, and the appearance of the surviving Schindlerjuden with the actors who played them is an unnecessary extension of the film's already clear moral statement, blurring the distinction between documentary and fictionalized narrative. The other objection is that the appearance of the girl in the red coat during the liquidation of the Kraków ghetto is a too-showy use of film technique in what should be a gripping, realistic scene. The former objection is a highly subjective one: For many, the film needs something to soften the harshness of the story's catharsis. For others, the answer is simply, "Let Spielberg be Spielberg," a gifted but traditional storyteller whose vision of the material he chooses is invariably personal. It's the second objection that gets to the heart of what film criticism is all about. I think David Thomson, in his brief essay on Schindler's List in Have You Seen ... ?, puts the objection most provocatively when he observes, "With that one arty nudge Spielberg assigned his sense of his own past to the collected memories of all the films he had seen. All of a sudden, the drab Krakow vista became a set, with assistant directors urging the extras into line.... It was an organization of art and craft designed to re-create a terrible reality done nearly to perfection. But in that one small tarting up ..., there lay exposed the comprehensive vulgarity of the venture." I can't be as harsh as Thomson, for one thing because when I saw the film in the theater shortly after its release in 1993, I didn't notice the red coat -- the one note of color in the middle of the black-and-white film -- because I am mildly red-green colorblind. (It's difficult to explain to the non-colorblind, but those of us with the color deficiency usually see the color in question, but it's not quite the same color that the normally sighted see.) I did, however, notice the little girl: The framing by Spielberg and cinematographer Janusz Kaminski puts her in the center of the action and makes her search for a hiding place evident even in a long shot. What I did miss that time was the reappearance of the girl's body in a stack of corpses later in the film, something that would be evident to anyone who had earlier seen the red of the coat. Later, when I saw the film on video, after having read about the controversy over the red highlight, I was able to perceive the color -- not so intense for me as perhaps for you, but once brought to my attention inescapable -- and to be shocked by its reappearance in the later scene. But only when I watched the film again last night did I realize the function of the "arty nudge": When we first see the girl in the red coat, we see her from the point of view of Schindler (Liam Neeson) himself, on a hillside above the ghetto. And when we see her body, we are seeing it again from the point of view of Schindler, visiting the cremation site where Amon Goeth (Ralph Fiennes) has been ordered to burn the bodies of those killed in the liquidation of the ghetto. It is a subtle but effective move because it coincides with (or perhaps precipitates) Schindler's decision to try to save as many of his Jewish workers as he can. Is it "arty" or "tarting up" or "vulgar"? Perhaps it is, but it's also effective filmmaking. And only the fact that the Holocaust remains so large and sacrosanct an event in the moral history of the West raises the question of whether "effective filmmaking" is inappropriate to such a subject.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)