A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Sunday, August 14, 2016

The Lady Eve (Preston Sturges, 1941)

Preston Sturges, who was a screenwriter before he became a hyphenated writer-director, has a reputation for verbal wit. It's very much in evidence in The Lady Eve, with lines like "I need him like the ax needs the turkey." But what distinguishes Sturges from writers who just happen to fall into directing is his gift for pacing the dialogue, for knowing when to cut. What makes the first stateroom scene between Jean (Barbara Stanwyck) and Charles (Henry Fonda) so sexy is that much of it is a single take, relying on the actors' superb timing -- and perhaps on some splendid coaching from Sturges. But he also has a gift for sight gags like Mr. Pike (Eugene Pallette) clanging dish covers like cymbals to demand his breakfast. And his physical comedy is brilliantly timed, particularly in the repeated pratfalls and faceplants that Fonda undergoes when confronted with a Lady Eve who looks so much like Jean. Fonda is a near perfect foil for gags like those, his character's dazzled innocence reinforced by the actor's undeniable good looks. There's hardly any other star of the time who would make Charles Pike quite so credible: Cary Grant, for example, would have turned the pratfalls into acrobatic moves. The other major thing that Sturges had going for him is a gallery of character actors, the likes of which we will unfortunately never see again: Pallette, Charles Coburn, William Demarest (who made exasperation eloquent), Eric Blore, Melville Cooper, and numerous well-chosen bit players.

Saturday, August 13, 2016

Shaun the Sheep Movie (Mark Burton and Richard Starzak, 2015)

The look of Aardman Animations' stop-motion characters hasn't changed much in the years since the first Wallace and Gromit short in 1990, though the humanoid characters have become more diverse. We now see people of color, including a Muslim woman wearing a hijab, on the street. And the basic slapstick humor hasn't changed, either. It still has that essentially British overtone, even in Shaun the Sheep Movie, which has no intelligible dialogue. I doubt, for example, that Pixar, even though its films are perceptibly influenced by Aardman, would venture into the kind of fart jokes and the gags based on the anus of a pantomime horse that are on display in this movie. And all of that is to the good. For what the Aardman films do so well -- especially the ones by Nick Park, who created Shaun and his colleagues, and is listed as executive producer on this film -- is revive the fine art of Sennett and Chaplin and Keaton and Arbuckle, the masters of silent slapstick comedy. Aardman has the advantage that its actors are clay and not flesh, so they can undergo assaults that would obliterate even so resilient an actor as Buster Keaton, but it succeeds in making its characters believable by putting limits on the mayhem. We know that the actors are putty in the hands of the animators, and yet somehow we wince at their peril when they're trapped by the villain on the edge of what a sign describes as "Convenient Quarry." (One of the delights of the movie, which makes you want to watch it again, are the blink-and-you-miss-it gags on the fringe of the action, like that sign.) Shaun the Sheep Movie was nominated for the best animated feature Oscar, but lost to Pixar's brilliant Inside Out. These are grand times indeed for animation.

Friday, August 12, 2016

The Conversation (Francis Ford Coppola, 1974)

The technology used in it may have dated, but The Conversation seems more relevant than ever. When it was made, the film was very much of the moment: the Watergate moment, which was long before email and cell phones. Julian Assange was only 3 years old. What has kept Coppola's film alive is that he had the good sense to make it a thriller about the consequences of knowledge. The real victim of Harry Caul's snooping is Harry Caul himself, the professional whose delight in what he can do with his microphones and tape recorders begins to fade when he realizes that technology is not an end in itself. It is one of the great Gene Hackman performances from a career crowded with great and varied performances. Ironically, the film that The Conversation most reminds me of today is The Lives of Others, Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck's 2006 film about eavesdropping by the Stasi in East Germany, which was praised by conservatives like John Podhoretz and William F. Buckley and called one of "the best conservative movies of the last 25 years" by the National Review for its account of surveillance by a communist regime. But Harry Caul is a devout Roman Catholic and an entrepreneur, making his living with the same technology and the same techniques as the Stasi spy of Donnersmarck's film -- capitalism alive and well. The film is something of a technological marvel itself: The great sound designer and editor Walter Murch was responsible for completing it after Coppola was called away to work on The Godfather, Part II, and the texture of the film depends heavily on the way Murch was able to manipulate the complexities of sound that form the key scenes, especially the opening sequence in which Caul is conducting his surveillance of a couple in San Francisco's crowded and busy Union Square. It's true that Murch cheats a little at the ending, when the line, "He'd kill us if he got the chance," is repeated. Caul had extracted it from a distorted recording, and took it to mean that the couple (Cindy Williams and Frederic Forrest) were in danger from the man who commissioned the surveillance. But at the end, the line is heard again as "He'd kill us if he got the chance," an emphasis that reveals to Caul, too late, that they are the killers, not the victims. It's unfortunate that so much depends on the discrepancy between the way we originally hear the line and the later delivery of it. Still, I don't think it's a fatal flaw in a still vital and gripping movie.

Thursday, August 11, 2016

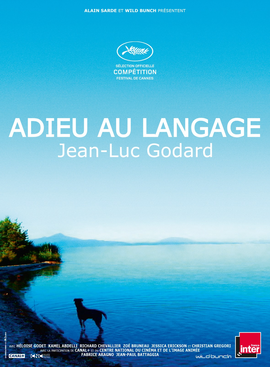

Goodbye to Language (Jean-Luc Godard, 2014)

Is Goodbye to Language the autumnal masterwork of a genius filmmaker? Or is it just an exercise in playing with old techniques -- montage, jump cuts, oblique and fragmented narrative -- in a new (at least to Godard) medium -- 3D? Not having seen the film in 3D, I'm not perhaps fully qualified to comment, but I have to say that it didn't open any new insights for me into the potential of film or the Godard oeuvre as a whole. That in the film Godard makes the wanderings of a dog more coherent and interesting than the conflicts of his human characters is telling: He is obviously more emotionally invested in the dog, played by his own pet, Roxy Miéville, than in the people, whose story can only be pieced together from the fragments of what they do and say to each other. Language, as the title suggests, is subordinate to direct sensation, in which the dog has an advantage over the incessantly chattering and analyzing humans. Godard suggests this through a barrage of quotations from philosophers and novelists, which keep tantalizing us away from simply absorbing the images that he also floods the film with -- the cinematographer, responsible for many of the novel 3D effects, is Fabrice Aragno. Even without 3D, Goodbye to Language is often quite beautiful, with its saturated colors, but I'm not convinced that it adds up to anything novel or revelatory.

Wednesday, August 10, 2016

David Copperfield (George Cukor, 1935)

As long as there are novels and movies, there will be people trying to turn novels into movies. Which is a task usually doomed to some degree of failure, given that the two art forms have significantly different aims and techniques. Novels are interior: They reveal what people think and feel. Movies are exterior: Thoughts and feelings have to be depicted, not reported. Novels breed reflection; movies breed reaction. Novel-based movies usually succeed only when the genius of the filmmakers exceeds that of the novelist, as in the case, for example, of Alfred Hitchcock's transformation (1960) of Robert Bloch's Psycho, or Francis Ford Coppola's extrapolation (1972) from Mario Puzo's The Godfather. We mostly settle for, at best, a satisfying skim along the surface of the novel, which is what we get in Cukor's version of Dickens's novel. I'm not claiming, of course, that Cukor or the film's producer, David O. Selznick, was a greater genius than Dickens, but together -- and with the help of Hugh Walpole, who adapted the book, and Howard Estabrook, the credited screenwriter -- they produced something of a parallel masterpiece. They did so by sticking to the visuals of the novel, not just Dickens's descriptions but also the illustrations for the original edition by "Phiz," Hablot Knight Brown. The result is that it's hard to read the novel today without seeing and hearing W.C. Fields as Micawber, Edna May Oliver as Betsey Trotwood, or Roland Young as Uriah Heep. The weaknesses of the film are also the weaknesses of the book: women like David's mother (Elizabeth Allan) and Agnes Wickfield (Madge Evans) are pallid and angelic, and David himself becomes less interesting as he grows older, or in terms of the movie, as he ceases to be the engaging Freddie Bartholomew and becomes instead the vapid Frank Lawton. But as compensation we have the full employment of MGM's set design and costume departments, along with a tremendous storm at sea -- the special effects are credited to Slavko Vorkapich.

Tuesday, August 9, 2016

Room (Lenny Abrahamson, 2015)

|

| Jacob Tremblay and Brie Larson in Room |

Monday, August 8, 2016

The Wild Bunch (Sam Peckinpah, 1969)

"It ain't like it used to be, but it'll do." The last line of The Wild Bunch, spoken by Edmond O'Brien's Sykes, sums up the film's prevailing sense that something has been lost, namely, a kind of innocence. Myths of lost innocence are as old as the Garden of Eden, and the Western as genre has always played on that note of something unspoiled being swept away with the frontier, though seldom with such eloquent violence as Peckinpah's film. Notice, for example, how many children appear in the movie, often in harm's way, as if their innocence was under attack. The film begins with a group of children at play, but what they're playing with is a scorpion being tormented by a nest of ants. Finally, after the grownups have had a major shootout, endangering other innocents, including a mostly female prohibitionist group, the children set fire to their little game, creating a neat image of hell that sets the tone for the rest of the film. Children, Peckinpah seems to be saying, have only a veneer of innocence, one that's easily removed. So we have children not only under fire but also sometimes doing the firing. They treat the torture of Angel (Jaime Sánchez) as a game, running after the automobile that is dragging him around the village. Not many films use violence for such integral purpose, and not many films have been so wrong-headedly criticized for being violent. Before it was re-released in 1995, Warner Bros. submitted the newly extended cut of the film to the ratings board, which tried to have it labeled NC-17 -- usually a kiss of death because many newspapers refused to advertise movies with that rating. Ordinarily, I'd applaud any effort by the board to treat violence with the same strictness that it treats sex and language, but this decision only emphasizes the shallow, formulaic nature of the board's rulings. An appeal resulted in overturning the rating, so the film was released with an R. Film violence has escalated so much in recent years that if it weren't for the bare breasts in some scenes, The Wild Bunch might get a PG-13 today. I also think the real reason for the emphasis on violence in commentaries on The Wild Bunch is a puritanical one: The movie is too much fun for some people to take seriously. It has superbly staged action scenes, like the hijacking of the train and the demolition of the bridge. And it has entertaining, career-highlight performances by William Holden, Ernest Borgnine, Warren Oates, Ben Johnson, and Robert Ryan. The cinematography by Lucien Ballard and the Oscar-nominated score by Jerry Fielding are exceptional. And it's "just a Western," so no high-toned viewers need take it seriously, though surprisingly the Academy did nominate Peckinpah, Walon Green, and Roy N. Sickner for the writing Oscar. They lost to William Goldman for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, a movie that feels flimsier as every year goes by.

Sunday, August 7, 2016

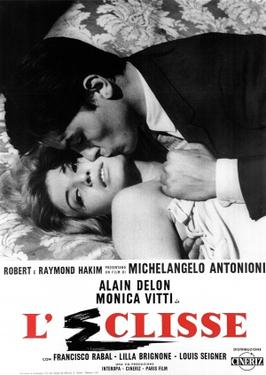

L'Eclisse (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1962)

I'm still an admirer of Pauline Kael's film criticism, but it has dated. She did a great service in her heyday, the 1970s, by cutting through the thickets of snobbery to advance the careers of American filmmakers like Robert Altman and Sam Peckinpah. But that often meant attacking "art house" filmmakers like Antonioni and Alain Resnais, poking at their supposed intellectual pretensions. Although I was never a "Paulette," my career as a professional film critic having been a matter of a few months reviewing for a city magazine, I think I qualified at least as a Kaelite: one who took her point of view as definitive. For a long time, I scoffed at films by Antonioni, Resnais, and others like Ingmar Bergman who got glowing notices from the high-toned critics but zingers from Kael. The bad thing is that I missed, or misinterpreted, a lot of great movies; the good thing is that I can spend my old age rediscovering them. And L'Eclisse is a great movie. One that, to be sure, Kael could dismiss as "cold" and mock for its director's use of Monica Vitti as a vehicle for his views on "alienation." I will grant that Vitti's limited expressive range can be something of a hindrance to full appreciation of the film. But it would have been a very different movie if a more vivid actress like Jeanne Moreau or Anna Karina or even Delphine Seyrig had played the role of Vittoria. Vitti's marmoreal beauty is very much the point of the film: She is irresistibly attractive and at the same time frozen. Alain Delon's lively Piero begins to become blocked and awkward in his attempts to rouse her passion. In the opening scene, in which Vittoria tells Riccardo (Francisco Rabal) that she's leaving him, the two behave in an almost robotic, mechanical way, unable to release anything that feels like a natural human emotion at the event. We see later that Vittoria is able to let herself go, but only when sex is not in the offing and when she is playing someone other than herself: i.e., when she blacks up and pretends to be an African dancer. But Marta (Mirella Ricciardi) puts a stop to this by saying "That's enough. Let's stop playing Negroes." Marta, a colonial racist who calls black people "monkeys," evokes the repressive side of European civilization, but L'Eclisse transcends any pat statements about "alienation" through its director's artistry, through the way in which Antonio plays on contrasts throughout. We move from the slow, paralyzed male-female relationships to the frenzy of the stock exchange scenes, from Vittoria's rejection of Piero's advances to scenes in which they are being silly and having fun. Nothing is stable in the film, no emotion or relationship is permanent. And the concluding montage of life going on around the construction site where Vittoria and Piero have seemingly failed to make their appointment is one of the most eloquent wordless sequences imaginable."Some like it cold. Michelangelo Antonioni on alienation, this time with Alain Delon and, of course, Monica Vitti. Even she looks as if she has given up in this one."--Pauline Kael, 5001 Nights at the Movies

Saturday, August 6, 2016

The Searchers (John Ford, 1956)

Every time I watch The Searchers I find myself asking, is this really a great movie? It took seventh place on the 2012 Sight and Sound poll that ranks the best movies of all time. For my part, I think Red River (Howard Hawks, 1948) a richer, more satisfying film -- and, incidentally, the one that taught John Ford that John Wayne could act. And among Ford films, I prefer Fort Apache (1948) and even Stagecoach (1939). The Searchers is riddled with too many stereotypes, from John Qualen's "by Yiminy" Swede to the "señorita" who clatters her castanets while Martin Pawley (Jeffery Hunter) is trying to eat his frijoles, but most egregiously the "squaw" (Beulah Archuletta) whom Martin accidentally buys as a wife. (Notably, the two most prominent Native American roles in the film are played by Archuletta, whose 31 IMDb credits are mostly as "Indian squaw," and Henry Brandon, who was born in Germany, as Scar.) There is too much not very funny horseplay in the film, a lot of it having to do with the humiliation of Martin by Ethan Edwards (Wayne). Martin also takes a drubbing from the woman who loves him, Laurie Jorgenson (Vera Miles). It's almost as if, dare I suggest, the 62-year-old Ford took a sadistic delight in beating up on handsome young men, since he does it again in the film with Patrick Wayne's callow young Lt. Greenhill. (Do I really need to explain the significance of the way Ward Bond's Reverend keeps belittling the lieutenant's sword as a "knife"?) And although Monument Valley, especially as photographed by Winton C. Hoch, is a spectacular setting, by the time of The Searchers Ford had used it so often as a stand-in for the entire American West that he has reduced it to the status of a prop. Yet by the time Ethan Edwards stands framed in the doorway, one of the great concluding images of American films, I'm resigned to the fact of the film's greatness. It consists in what the auteur critics most admired in directors: It is a very personal film, imbued in every frame with Ford's sensibility, rough-edged and wrong-headed as it may be. And Wayne's enigmatic Ethan Edwards is one of the great characters of American movies -- not to mention one of the great performances. We never find out what motivates his obsessive search for Debbie (Natalie Wood), leading some to speculate unnecessarily that she's really his daughter by Martha Edwards (Dorothy Jordan), his brother's wife. And his radical about-face when he finally lifts Debbie, a reprise of what he did with the child Debbie (Lana Wood) at the start of the film, and takes her home, after threatening to kill her throughout the film, is as enigmatic as the rest of his behavior. But it's a human enigma, and that's what matters. Ford's strength as a director always lay in his heart, not his head. In the end, The Searchers really tells us as much about John Ford as it does Ethan Edwards.

Friday, August 5, 2016

The Conformist (Bernardo Bertolucci, 1970)

Of all the hyphenated Jeans, Jean-Louis Trintignant seems to me the most interesting. He doesn't have the lawless sex appeal of Jean-Paul Belmondo, and he didn't grow up on screen in Truffaut films like Jean-Pierre Léaud, but his career has been marked by exceptional performances of characters under great internal pressure. From the young husband cuckolded by Brigitte Bardot in And God Created Woman (Roger Vadim, 1956) and the mousy law student in whom Vittorio Gassman tries to instill some joie de vivre in Il Sorpasso (Dino Risi, 1962), through the dogged but eventually frustrated investigator in Z (Costa-Gavras, 1969) and the Catholic intellectual who spends a chaste night with a beautiful woman in My Night at Maud's (Eric Rohmer, 1969), to the guilt-ridden retired judge in Three Colors: Red (Krzysztof Kieslowski, 1994) and the duty-bound caregiver to an aged wife in Amour (Michael Haneke, 2012), Trintignant has compiled more than 60 years of great performances. His most popular film, A Man and a Woman (Claude Lelouch, 1966), is probably his least characteristic role: a romantic lead as a race-car driver, opposite Anouk Aimée. His role in The Conformist, one of his best performances, is more typical: the severely repressed Fascist spy, Marcello Clerici, who is sent to assassinate his old anti-Fascist professor (Enzo Tarascio). Marcello's desire to be "normal" is rooted in his consciousness of having been born to wealth but to parents who have abused it to the point of decadence, with the result that he becomes a Fascist and marries a beautiful but vulgar bourgeoise (Stefania Sandrelli). Bertolucci's screenplay places a heavier emphasis on Marcello's repression of homosexual desire than does its source, a novel by Alberto Moravia. In both novel and film, the young Marcello is nearly raped by the chauffeur, Lino (Pierre Clémenti), whom Marcello shoots and then flees. But in the film, Lino survives to be discovered by Marcello years later on the streets the night of Mussolini's fall. Marcello, whose conformity does an about-face, sics the mob on Lino by pointing him out as a Fascist, and in the last scene we see him in the company of a young male prostitute. This equating of gayness with corruption is offensive and trite, but very much of its era. Even the sumptuous production -- cinematography by Vittorio Storaro, design by Ferdinando Scarfiotti, music by Georges Delerue -- doesn't overwhelm the presence of Trintignant's intensely repressed Marcello, with his stiff, abrupt movements and his tightly controlled stance and walk. If The Conformist is a great film, much of its greatness comes from Trintignant's performance.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

_poster.jpg)